Wonder woman Yasmine Hamdan takes a breather to give the lowdown on her new album

‘I just got my French passport’, says Yasmine Hamdan with a small burst of excitement, the night before her appearance at The Music Room in Dubai presented by Vibe Series. ‘I’m attached to Paris, actually, but I do not want to belong’, she remarks as we discuss the concepts of belonging and inclusion. ‘I would rather live on the margin – and I feel more comfortable living there, not belonging to a place’. I ask her why. ‘Because,’ she responds, ‘I cannot pretend that I know how to do that. I’m not sure I know what it’s like to belong to one place.’

A myth exists around Hamdan. She performs at what some commentators have described as the ‘intersection of sexy electronica and iconic Arab tradition’, and is controversial in some quarters for this very reason. She is not scared to say things, or to talk about sexuality or eroticism. She is also unwilling to let herself be controlled by the codes and rules of traditional Arabic music. In short, she is unwilling to censor or to be something that she is not. Indeed, the starting point for many of the lyrics on her new album, Al Jamilat (The Beautiful Ones), emerged from encounters with ex-criminals, perverts, war fighters, gigolos, poets, and drug addicts, all of whom have, admits Hamdan, inspired her in some way. ‘Their anger echoes a sense of hopelessness, and the mixed feelings I have regarding the ongoing turmoil in Lebanon and the region’.

Courtesy Yasmine Hamdan and Crammed Discs

Is Al Jamilat therefore an angry album? She laughs. ‘No, no, but anger can give you a creative impulse’, she is quick to mention. ‘I think we’re all angry in some places, in some ways, and we deal with it. But no, this album is very much about tenderness and womanhood. It’s also very much about colours and sensuality and travelling and movement. But I have some songs that – not on an immediate level – are more political and more social and, through my characters, say things about tormented people who live a certain violence. It’s more related to corruption, to the sad things we’re living today.’

‘Is this in relation to Beirut?’ I ask her. ‘It is in relation to Beirut, but also to the state of the world in general. I don’t think Beirut is an exception. The world is becoming – for some people – more and more difficult to be in. I can feel that around me, at least. My characters are Lebanese, but they could be in India or Pakistan or any other place in the world.’ Hamdan goes on to talk about the importance of music: ‘This relationship and this dialogue that I initiate inside my music – with where I come from, with my roots, with this culture – is essential. Through music you can resist, and through music you can challenge yourself and challenge the things around you; and through music you can learn. It’s painful sometimes, because I’m not happy with what’s going on, and sometimes I get very depressed when I [turn on] the news and when I see what’s happening; so, I’ve decided to push myself towards the margins a little bit, because I don’t want this darkness to take over.’

Hamdan’s greatest asset has always been her voice. A performer, lyricist, composer, and actress, she is an example of what is possible within the realms of alternative Arabic music. For her 2012 debut solo album, Ya Nass (Oh People), she included her own compositions as well as interpretations of beloved classics, picking out certain melodies and choruses, playing with various varieties of Arabic, and rendering sometimes complex and tonal Arabic songs in simple chords and pop tones. Whether one likes the end result or not depended on their definition of what Arabic music is.

Hamdan describes Ya Nass as her personal, modern take on Arabic pop. Al Jamilat, in contrast, is an exploration of the mutations at work within the Arab world. In the notes she wrote for the Brussels-based record label Crammed Discs, on which the album is soon to be released, she explains much of the thinking behind the new album and her songwriting. ‘When I am composing, I want to explore different possibilities of textures and grooves together, regardless of where they come from or what they refer to, regardless of codes and formats’, she wrote. ‘I am interested in exploring encounters where worlds meet, beyond musical genres or musical worlds. I like to find this place where the mix becomes intuitive, and where the encounter with Arabic music becomes effortless. It fits me, because I belong to different places; I’ve lived in different cultures and I have learned to appropriate and create from a hybridised point of view. I actually see that as a creative asset, something rather liberating. I think being plural and having mixed identities is a state in which many people find themselves today.’

Courtesy Yasmine Hamdan

The end result is a sometimes trippy meandering through various elements of global music, although Hamdan’s vocals anchor the album firmly in the Arab world. Her voice has been many things over the years: sensuous, deep, hypnotic, gentle, smoky, restless. Here, it veers between the sensual and the restless as Al Jamilat fuses elements of electronica, indie, folk, and Arabic melodies into a patchwork of moods and memories. ‘I miss the Beirut I used to know’, she says, discussing memory, ‘and at the same time, this Beirut I used to know was very painful and I ran away from it somehow. We need to accept that things are changing and there is going to be a lot of struggle. The whole region is difficult and it’s suffocating, especially if you’re a young person and you need opportunities. You need to be inspired, you need to feel positivity and you need to be challenged. On a cultural level, also, there is an identity crisis, and that identity crisis is creating problems; and people are inventing fast solutions, and those solutions are intoxicating somehow.’

‘An identity crisis?’ I ask. ‘Yeah, I have a sense that people are searching for values’, she replies. ‘When I connected [through music] to memory and the past or with something to do with history or roots, it gave me answers and somehow made me feel good about myself; it opened doors for me. Now, I think that our societies are linked to the past through the wrong channels. Culturally, the Arab world was – especially in the 40s, 50s, and 60s – extremely dynamic; and yet, I feel there has been a small rupture with this movement. People are searching for themselves through different channels, but those channels can be repressive.’

‘I’ll give you example’, she adds. ‘Every time I go back to Beirut, I connect to the city through the taxi drivers; I get the sense and the vibe of the place through them: the different tensions, the politics, the corruption, because they are in the middle of it. I’ve also started to realise that, less and less, people are listening to quality music, and more and more are giving up on this globalised, horrible, industry of “tisk tisk, tum tum” music, as I call it. And, if you go deeper into what this music stands for, you realise that women are portrayed as sexual objects and that any depth or reflection or spirituality is completely absent.’

I belong to different places; I’ve lived in different cultures and I have learned to appropriate and create from a hybridised point of view. I actually see that as a creative asset, something rather liberating.

Of all the songs, only one – the Mahmoud Darwish poem, Al Jamilat, which lends its name to the title of the album and for which Hamdan composed music – contains lyrics not written by the artist. It is this song, however, that she believes encapsulates the overall spirit of the album: an ode to womanhood and celebration of beauty in its multiplicity and contradictions. According to Hamdan, her female characters are bold, ambivalent and dominant, utilising humour, sarcasm, and devotion as powerful means of seduction. ‘I see those feminine characters as skillful witnesses, non-conventional and non-perfect figures of change, redemption, and awakening’ she wrote in her notes for Crammed Discs. ‘They do not serve their home, fatherland, or religion: they express themselves in some mode of life that is personal, emancipated, and free.’

By Tania Feghali (courtesy Crammed Discs)

I have interviewed Hamdan three or four times, but we have never met until now. She always talks confidently and thoughtfully, and it’s currently early evening on the night before her Dubai gig. She drinks water and walks from room to room, having arrived from Doha only a few hours earlier. Vaguely, she recalls the last time we spoke. Back then, she had been strolling through the streets of Paris, her voice occasionally breaking amidst the sound of mopeds, screaming children, and the chit-chat of passersby. A combination of exhaustion, touring, and airplanes had stretched her voice to breaking point. Now, she insists, she is fine, despite three years on the road with Ya Nass.

Hamdan has been working on Al Jamilat since last February, when she first began putting together demos and writing as she toured, living on trains and planes and sleeping in hotel rooms. Snippets were recorded in Paris and Beirut, but the majority of the 11 demos were laid down in New York City at Sonic Youth’s studio in Hoboken before being finalised in London by British producers Luke Smith and Leo Abraham. ‘When you record and you’re still working and composing, you need to find some solitude. It took me some time to find that peace and that quiet and to be able to get my things together – to get my thoughts together, my ideas – but also to find the desire and to be inspired by things I wanted to do’, says Hamdan, who lives in Paris with her partner, the Palestinian film director Elia Suleiman. ‘It was very important for me to somehow challenge myself in a different way and to enter another zone. I had ideas, I had desires, and I had to make things happen. So, it was quite interesting as a process, and I eventually realised that I would – maybe on my next album – do it in a different way; but I’ve learnt a lot. I feel there is something very nomadic about this record. It’s in [the] movement.’

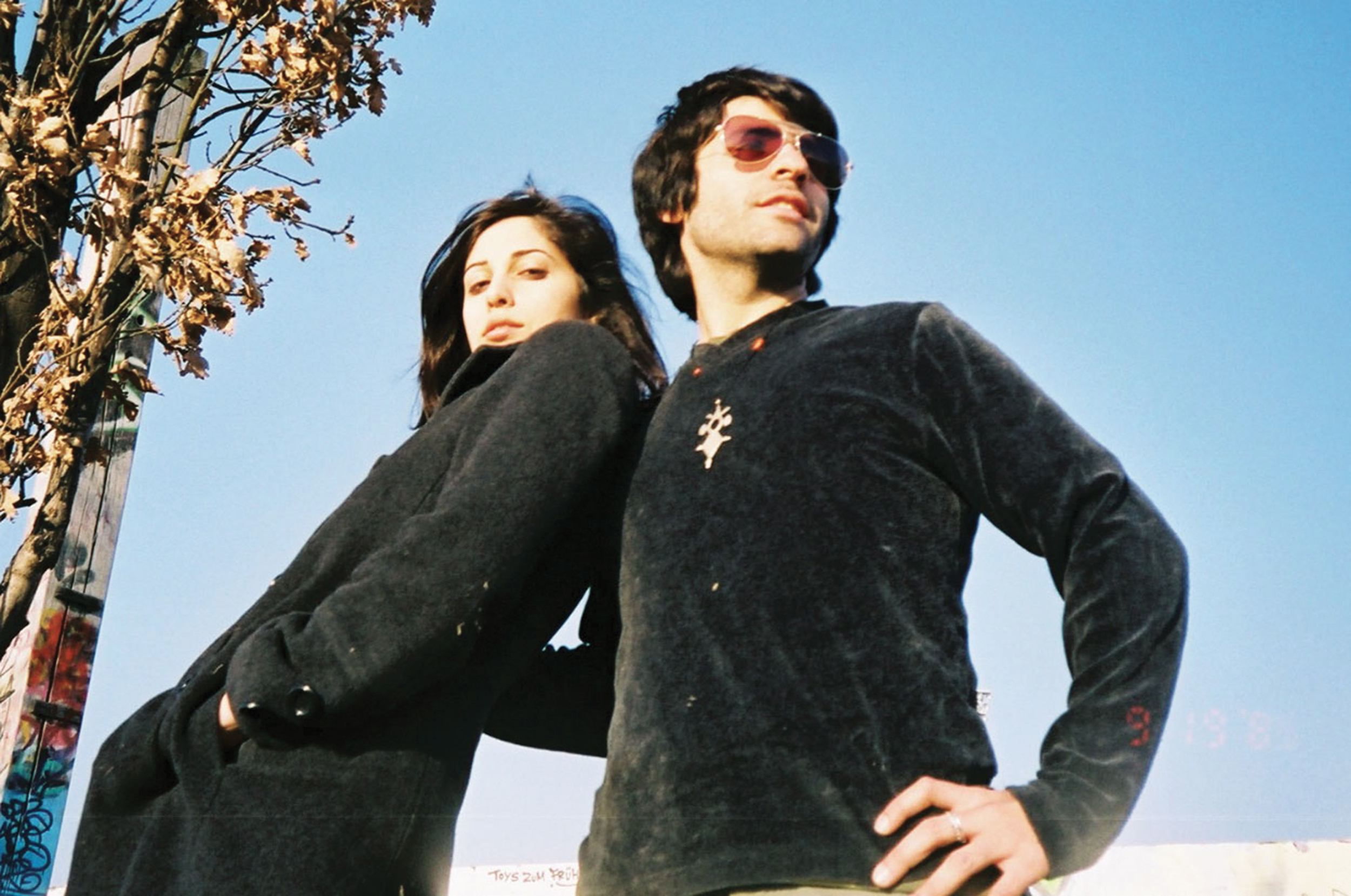

With Zeid Hamdan as Soapkills (courtesy Strictly Confidential Music Publishing)

The seed from which the album grew was the song Assi. Written during Hamdan’s years with Soapkills and her then musical partner, Zeid Hamdan, it had, however, never taken a finalised form. Revisiting it, she wanted violins, a bigger sound, something very local. ‘I wanted a lot of texture, a lot of colour; I wanted a diversity of moods. That was my aim’, she says. ‘I would take a rhythm, I would take a groove, I would take a sound, I would take a melody, and then shape it with different colours so that it became something very hybrid.’

That hybridity will not be to everybody’s taste. The album’s sound is a kaleidoscope of Middle Eastern instruments, grooves from Iraq and the Persian Gulf, Tuareg desert blues guitar licks, the grumbling sound of the buzuq, and rhythmic loops created either via live drums or vintage Arabic samples. It is through these samples that Hamdan’s love of the likes of Mohammed Abdel Wahab, Asmahan, Om Kolthoum, Leila Mourad, and Abdel Halim Hafez can be discerned. No discussion of Hamdan, of course, can realistically take place without reference to Soapkills, a duo that epitomised the carefree hedonism of postwar Beirut, re-imagining classical Arabic song with a quintessential Levantine take on trip-hop and electronica. It is through Soapkills that Hamdan is most widely known, especially in the wider Levant. Her success abroad is less easy to gauge, although her appearance in director Jim Jarmusch’s Only Lovers Left Alive, in which she performed as herself in a bar in Tangier, helped raise her international profile.

Although Sonic Youth’s Steve Shelley worked with Hamdan on Al Jamilat, as did the multi-instrumentalist Shahzad Ismaily and New York-based violinist Magali Charron, it’s her collaboration with Zeid Hamdan that perhaps stands out in particular. ‘You know, Zeid is a friend’, Hamdan tells me. ‘I just called him and it was very casual. I needed a grumpy buzuq – a buzuq that was not serious – and Zeid is great at that. I always see him when I’m in Beirut and have time.’ I ask her if she misses working with him, and she hesitates. ‘You know, at some point we arrived at something that was – I would say – the full bloom of our collaboration. I used to feel sad about the fact that we could not produce more music together; but if things are not happening, you cannot force them. I also felt, at some point, a certain frustration that we did not perform more as Soapkills, because we didn’t perform a lot on stage. But at the end of the day, things don’t happen by coincidence.

‘I guess this is part of why Soapkills remains the band that it was and why that sound remains that sound. It was really a historic period in time. It was at the end of the Civil War in Lebanon, and I don’t know if Soapkills fits in to today’s Beirut, in today’s world. And I don’t know if I fit. I’m a totally different person now.’

Cover image by Flavien Prioreau (courtesy Crammed Discs).