Saudi lieutenant colonel-cum-artist Abdulnasser Gharem enjoys his first US solo exhibition

Between two languages and worlds, Abdulnasser Gharem navigates a third discourse endemic to the pan-Arab narrative of exile and estrangement. The forty-three-year-old curator of Edge of Arabia born, raised, and living in Saudi Arabia did not have to cross seas to articulate tropes of displacement and duality, which are often staples of the hyphenated Arab experience. I spoke to Gharem in between two different exhibitions – Pause, his first US solo show at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), and Epicentre X, a group show the Arab American National Museum in Dearborn, Michigan. ‘It takes ages to find your story’, he told me. Across four decades, twenty-seven shows, twelve collections, and myriad thematic sculptures, he has come to discover that his own story remains a work in process.

Gharem is himself a duality. Donned in a traditional Saudi thobe and ghutra, he is all too conscious that his own life represents a chronicle of an educational confrontation of the latent artist and himself as an individual. ‘I remember sitting in front of the [computer on] the Internet in the nineties’, he said, ‘for hours … because it was like you were discovering a new source of knowledge’. An admirer of the Dadaists and Picasso, Gharem’s internalisation of abstraction ubiquitous in their work evidently served the purpose of channeling feelings that can only be captured through abstraction into critiques of tangible and concrete social realities. The artist’s exposure to contemporary art through the Internet incited a period of thorough research and exploration that transformed his practice from a transcription of landscapes to a provocation of mindscapes.

The Path (courtesy LACMA)

In the aftermath of the September eleventh attacks, Gharem found out that two of the reported hijackers had been former schoolmates; this propelled him into deep contemplation. ‘What if it [had been] me?’ he asked. ‘We were in the same school and same environment, [where] a lot of teachers were forcing us [to do certain things] and into the mosque, and I refused.’ The conundrum of being so connected by their upbringing, which resulted in such disparate outcomes, signified the point at which Gharem took a pause – the namesake of his exhibition at LACMA – to fuse together the seemingly unassailable rift between worlds through reconciliation amidst interludes. Gharem, too, realised that had to ride his own tides and find his own path.

The artist’s graduation from Riyadh’s King Abdulaziz Military Academy in 1992 was followed by years as an army officer, and later, lieutenant colonel, during which he had no means through which to channel his art. No galleries, studios, or art centres were around at the time, and it wasn’t until 2003 that he finally pursued his silent passion by attending the Al-Meftaha Arts Village in Abha, with goals of challenging ideas rather than aesthetically reinforcing culturally dominant ones. With this in mind, he participated in his first group exhibition, Shattah, alongside other Al-Meftaha artists.

Hemisphere (courtesy LACMA)

Without any galleries and studios around in which to showcase his art, Gharem originally realised his ideas through street displays. Preferring the confrontational authenticity of open-air displays to studios, his early work tapped into the consciousness of his onlookers. For his first piece, 2007’s Flora and Fauna, Gharem cocooned himself under an imported Australian tree of an invasive species to protest environmental degradation. A mixture of Arabian motifs and styles, the concepts behind his pieces, however contemporary, are sometimes lost on Western audiences unaccustomed to local geometric designs or the Arabic script. Yet, Gharem’s almost sarcastic appeal for ethos is underscored by an even deeper critique of what he calls ‘established ignorance’.

Making statements that reject ‘us versus them’ binaries, Gharem instead depicts a dissection of the human psyche as a common navigation of existential dichotomies

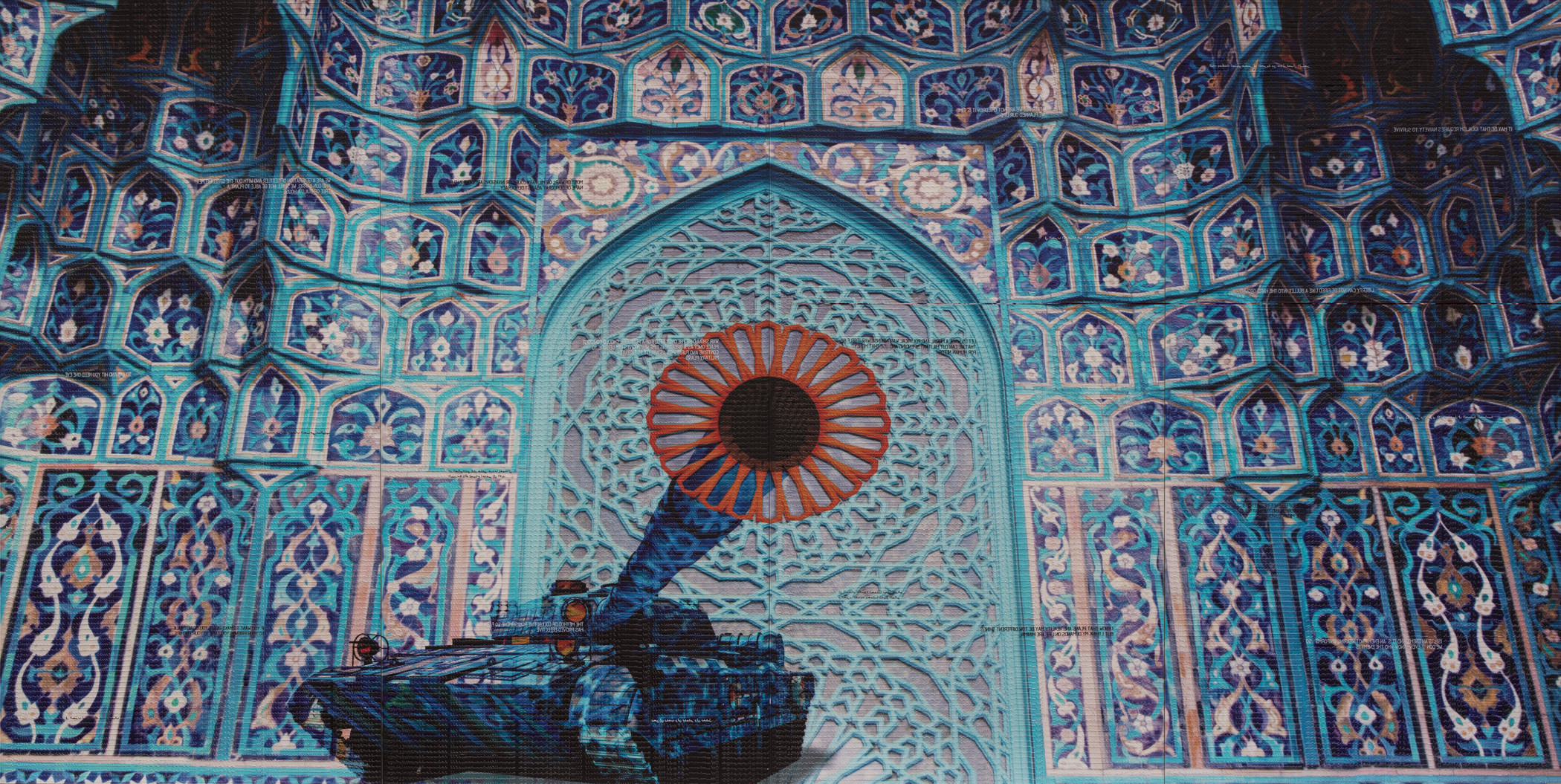

The tank superimposed on the portal of the Iranian mosque in Camouflage, or the helmet comprising the Hemisphere sculpture might seem to validate notions of the Arab world as inherently militaristic and characteristically war-torn; but accepting this would be to ignore Gharem’s wider cross-examination of political dogmatism as a universal phenomenon perhaps more salient in the West. The antiwar motifs of Camouflage and the dove in Message/Messenger serve as reminders of American anti-war counterculture from the days of the Vietnam and Iraq wars, just as the designations ‘Muslims’ and ‘non-Muslims’ on street signs on the road to Mecca (examined in 2011’s Road to Mecca) evoke images of similar ubiquitous signs from pre-seventies America. In other instances, these critiques are more overt, such as where the fragmented quotes from George W. Bush’s ‘War on Terror’ speech in 2013’s In Transit are concerned.

Camouflage

A piece sharing the show’s namesake, Pause, was painted on a repetition of rubber stamp patterns comprising a pixelated façade of the Twin Towers in the crux of their destruction – as if to recreate a digitised expression of the act of pausing. As minimalistic as it appeared, with the two buildings cradled by two golden arches on the far ends of the piece, it was highly intricate, constructed from hundreds of assorted Arabic and English letter stamps. Here, Gharem moved from critiques of authority and ideas to expressions of solidarity that have sombrely resonated with him as much as they have amongst his American audiences. While many of the pieces in the exhibition explored themes related to September eleventh, Pause was the artwork directly concerning the attack itself. The artist invited viewers to understand and reflect on the event not just as Americans or Arabs, but also – as per the minutely stamped text beside the piece – as the wife of the late Flight 93 pilot, Sandy Dahl. ‘If we learn nothing else from this tragedy,’ she said, we learn that life is short and there is no time for hate’.

Initially, Gharem’s goal of ‘activating the consciousness of [his] people’ was only partially met, as he sought a more visceral form of engagement with his audiences, many of whom were artists who found themselves in a struggle to creatively express their social and political frustrations. In 2011, Gharem founded his own studio in order to help youth hone their own creative conscience, with hopes to help catalyse an intellectual and ideological cascade through art. ‘I don’t just want them to be artists’, he said of his students, ‘but [also] players in society. There are a lot of talented people. They just need the right knowledge.’

The Stamp (courtesy LACMA)

Gharem, a self-described ‘example, and not an authority’, as well as an emphatic humanist who refuses to subscribe to any beliefs – ‘I’m not guarding any ideas’, he told me. ‘I can change my beliefs tomorrow morning.’ – is evidently more interested in highlighting similarities rather than differences. This outlook is perhaps the reason why he has been so successful in communicating a common social critique to audiences across borders, and is something from which activists, artists, and other agents of change in Saudi Arabia can draw inspiration. Making statements that reject ‘us versus them’ binaries, Gharem instead depicts a dissection of the human psyche as a common navigation of existential dichotomies.

‘Pause’ ran between April 16 and July 16, 2017 at LACMA.