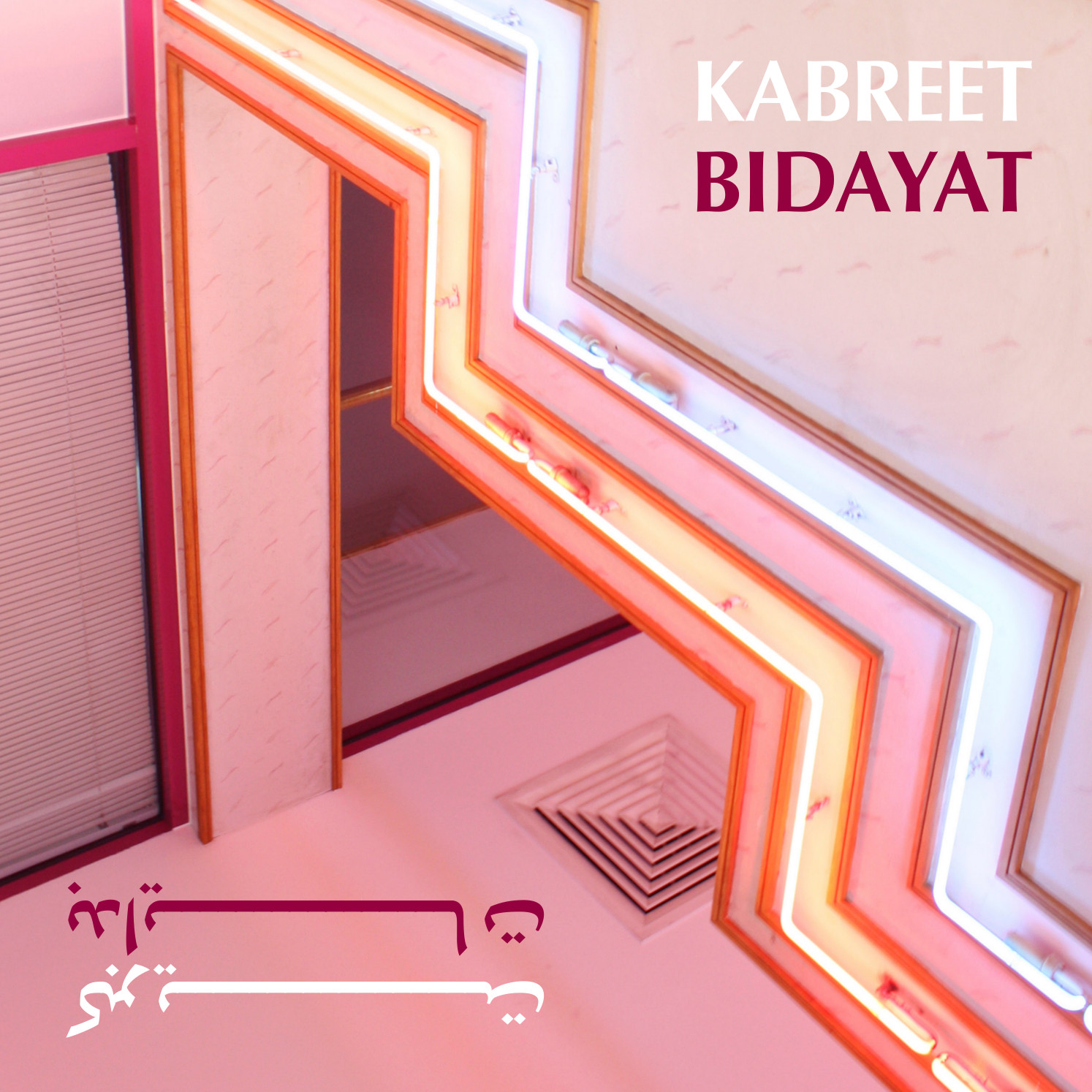

A match made in Berlin: Yemeni-German duo Kabreet is back with Bidayat

‘I think, musically, the title refers to the fact that we are slowly starting to actually feel like we are ready and owning this whole thing’, Ibi Ibrahim told me as he explained the reasoning behind choosing Bidayat (Beginnings) as the title for Yemeni-German duo Kabreet‘s (meaning ‘matchstick’ in Arabic) second album. Ibi’s multiple creative ventures are never just a ‘thing’, and the owning up is a journey from beginning to end. Joined by his bandmate Hanno Stecher, a former journalist, DJ, and hip-hop aficionado with a particular love for Beirut (which he visited on a whim after hearing some tunes from its underground bands), the two comprise Kabreet.

The Yemeni-German mélange the duo offers can easily be overlooked as an East-meets-West or fusion cliché, but it is anything but either. While Kabreet derives much of its lyrical inspiration from the Arab world, with Ibi using nostalgic cultural motifs in his artistic soul-searching, it does not look to sell itself as a ‘Middle Eastern’ band or regional phenomenon. The group is a product of an urban Berlin experience: a Yemeni visual artist dealing with the Arab world in his work decided to collaborate with a bohemian German intellectual with a love for what he jokingly calls ‘sexy Orientalist elevator music’.

Ibi Ibrahim (left) and Hanno Stecher (photo by Shane Thomas McMillan)

Kabreet has been sexy and experimental from the beginning. Their song Momken Bokra (Perhaps Tomorrow), whose video featured a well-known male Turkish belly dancer moving to Ibi’s words about his lovers, memorable and unmemorable. For Bidayat, Kabreet – after winning a grant from the Arab Fund for Arts and Culture (AFAC) – ventured into Beirut to record the album, collaborating with producer Fadi Tabbal and videographer Mohamed Abdouni. Regarding the album, I’d asked them if they could pick a few songs that captured its essence; they indulged me with answers, although not without cringing at the question. Both Ibi and Hanno see the album as a ride, with each song able to be experienced on its own and without needing a specific framework to be understood in. They both, however, have a particular affinity for the song Enta (You), an atmospheric, melancholic tribute to the late George Michael. With Hanno’s calm electronic piano in the background, Ibi tells in a tragic voice of the fluidity of gender, questioning if George was male or female.

I first played Enta on a still night in Beirut, as I was sitting on my balcony. I was immediately drawn to it, finding it effortless and unpretentious. For a second, I was in a haze, imagining myself dancing at a discotheque and forgetting about the sound of traffic outside and my neighbour Eman, fighting with the delivery boy who had parked in her spot again. Five days later, I heard the song again. I had drunkenly left an exhibition in town to head for more drinks with friends. As we drove down the highway to a bar called ‘Demo’, playing a mix of North African raï and Egyptian electro-chaabi, my friend let go of the wheel. Enta walad, enta bent, she sang, softly moving her hands. You are a girl, you are a boy. That moment was Kabreet and Enta; it was oddly specific, yet accidental. And it worked. In particular, it helped me better understand the video for the song, which was released a week later.

Abdouni, who shot the video in the Lebanese countryside, decided not to go for a word-for-word visual treatment of the song, but instead, add another layer to it. To Abdouni, it made perfect sense to cast his longtime friend Yumna Marwan in the video. When he first heard the lyrics, she was the first person to come to mind. Watching the video, it’s understandable to see why. Yumna gives the song a raw and sexual energy, quickly morphing from a young woman giggling in a field of flowers to an almost macho character confronting and yelling at a hidden lover. Inspired by a dinner conversation they’d had, Abdouni and Yumna decided to pay tribute to ‘tacky’ music promos from the early 2000s as well as the mundane, yet entertaining home videos popular at the time. The video is exactly that; it switches between being intimate and estranged, intense and calm, sexy and vulgar. It blends well with Kabreet’s music, giving it new visual vigour.

In a hyper-consumerist age, when musicians feel an increasing need to sell themselves along the lines of certain narratives, concepts, and frameworks, Kabreet does not

There’s more to the album than only Enta, however. Sakran (Intoxicated), which deals with the burdens of Imran, a young drunk man, is a song that is an almost accidental and ironic homage to nights out in Yemen. Imran is not only drunk from binge drinking, but also the current burdens plaguing contemporary Yemen, a country that has been torn apart by war and what many feel to be a conservatism with respect to cultural output. It starts with an Afro beat and enters into a speedier one reminiscent of the Lebanese music of the mid-nineties, similar to that on many of the songs by the postwar band The 4 Cats. Kalam (Words), on the other hand, has the feel of a lucid dream. Singing of love, lust, and temptation to a repetitive electronic drumbeat in the background, Ibi gives it a sexual tension through his seductive voice, and captures a moment of anxiety and awkwardness. This sexual melodrama continues in Shofni (See Me), centred around huzn, a state of sadness and melancholy. Here, Ibi sings to an unknown man, whose attention he tries to capture as he grows increasingly distant, experiencing states of joy, sadness, and confusion.

Other songs on the album are tributes to the folk culture of Yemen, which is known for its poetry revolving around mountains and everyday experiences. One such song is Yom Al Ahad (On Sunday), a traditional tune given a contemporary twist through its beat and Ibi’s elongations of Arabic words. In it, an unexpected Sunday journey is interrupted by an awaited, yet abandoned lover who arrives at someone’s door. Telling of the emptiness and boredom that often come with Sundays, it has a feel similar to Diana Haddad’s Ya Ahl Al Ishq (Oh, People of Love). The most emotionally intense number, perhaps, is Nahr Al Neel (The River Nile), which tells of the unrequited love between two men and their desire to get drunk under the river’s palm trees.

The lack of specificity is one of the main highlights of Bidayat. As previously mentioned, each song is an experience that can be enjoyed in itself. This multilayered experience is faithful to the personalities of both Ibi and Hanno, as both occupy multiple roles and positions without ever restraining themselves to just one. Ibi, being the artistic spectacle he is to many, wakes up in the morning and starts his days by splashing Yemeni coffee onto canvases, while playing early Samira Tawfik songs. Later, he sends his friends voice messages, letting them know he’s enjoying a glass of wine somewhere in Soho, to relax after a long day of researching for Ai Wei Wei. Hanno, on the other hand, likes talking about the playlists of his former ‘Berlin Berries’ parties – usually featuring Princess Nokia – while simultaneously commenting on a certain situation unfolding at the Beirut café he’s hanging out at. Imagine a DJ looking out the window, while some boys, girls, and those in that beautiful in-between grind to Azealia Banks’ 212 discussing melancholy as a potential space for calm and comfort. Meeting the pair over drinks is hot and confusing.

Bidayat is Ibi and Hanno in all their shapes and forms. Don’t search for a specific story or theme within it; the album is a journey, not towards a specific goal, but the constantly changing styles of a creative duo. In a hyper-consumerist age, when musicians feel an increasing need to sell themselves along the lines of certain narratives, concepts, and frameworks, Kabreet does not. What are they? That cool party you want to get invited to without showing too much effort to get on the guest list.