Why does Iranian artist Mahmoud Bakhshi panic in cinemas?

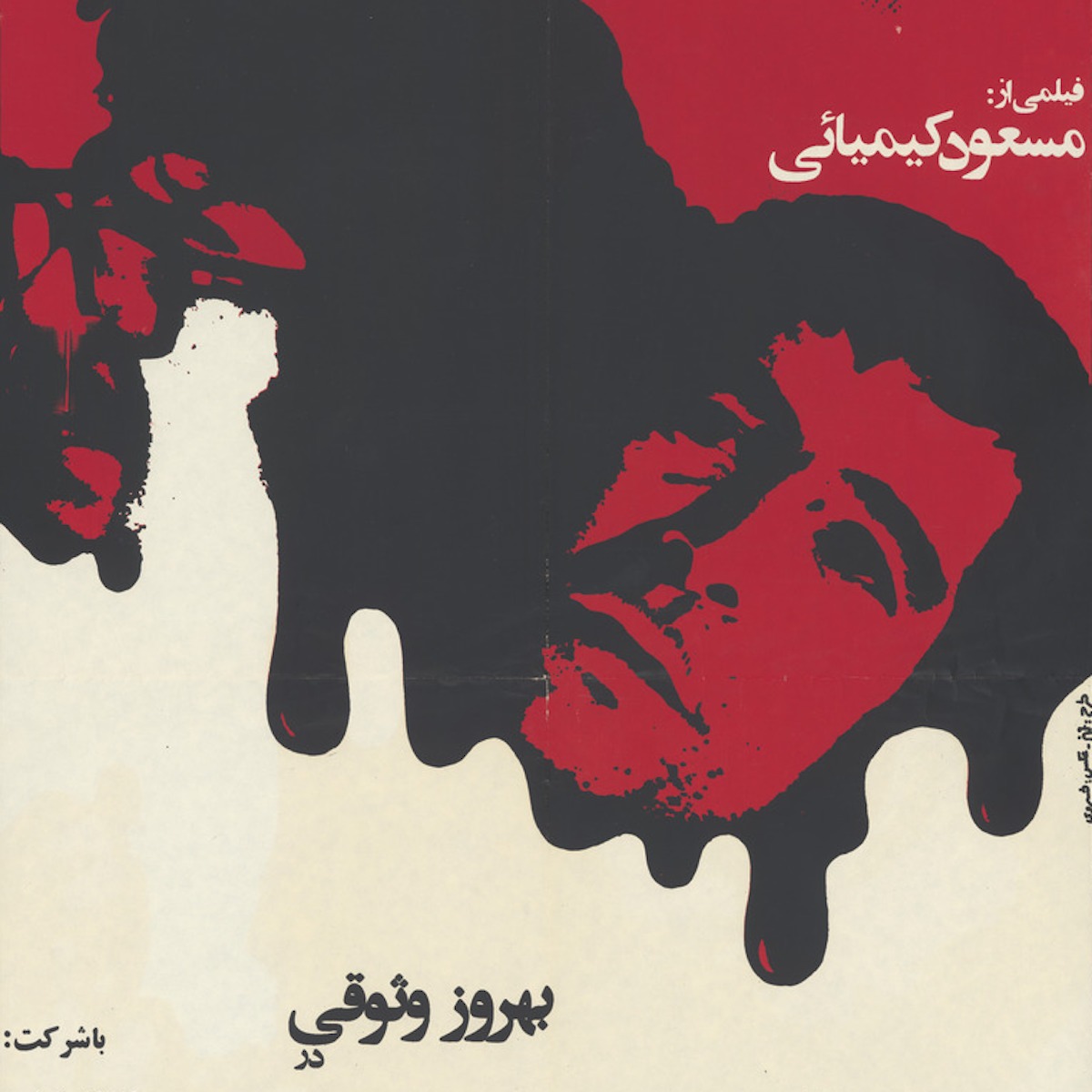

On a hot summer’s evening, six months before the 1979 Iranian Revolution, an affluent middle-class crowd settled into cinema seats in Abadan’s Cinema Rex. Gavaznha (The Deers), a new wave film by Masoud Kimiai touching on social issues, was screening. At 8:21 pm, as viewers’ eyes were transfixed by the illuminated images piercing through the darkness of the pitch-black room, four men barred the exits and imprisoned the people from outside. Dousing the cinema with petrol, they set the place alight, burning everyone within alive. According to various reports, the fire department – only 100 metres away – failed to respond in time.

Almost four decades later, the true motives and perpetrators behind the crime remain unknown; some have blamed Islamist groups, while others the Pahlavi government. In 1980, a year after the Revolution, executions of individuals linked to the incident – including that of the lone surviving arsonist – took place. The Cinema Rex affair wasn’t the only one of its kind, however; there was a spate of similar crimes committed during the build-up to the Revolution, and artist Mahmoud Bakhshi still to this day feels claustrophobic and panicky whenever cinema doors close.

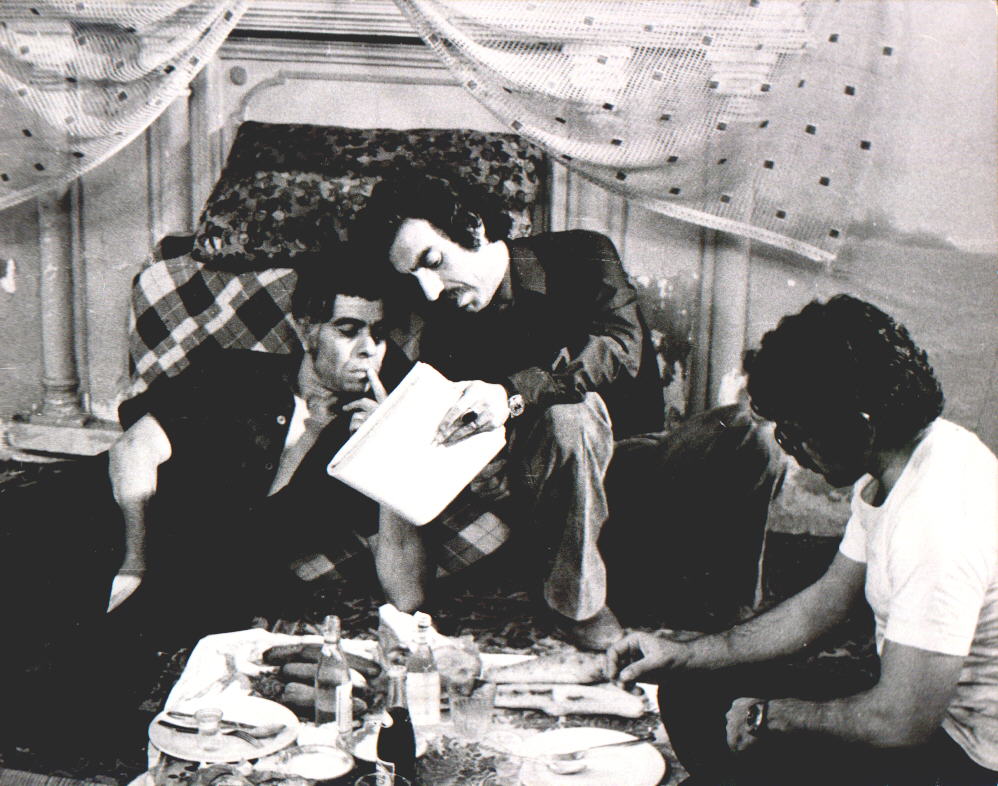

Behrouz Vossoughi (left), Masoud Kimiai (centre), and Faramarz Gharibian on the set of The Deers

The Deers presented a critical view of then-present-day Iran as seen through the eyes of characters at the lower rungs of society. As a result of the Shah’s Enghelab-e Sepid (‘White Revolution’), uneducated and unskilled farmers poured into industrial capitals. Believing in empty promises, many economic migrants risked what little they had for a chance in cities like Tehran, Esfahan, and oil-rich Abadan, only to end up unemployed and dependent on drugs. Kimiai’s film initially swerved past censors until the third edition of the Tehran International Film Festival, where its critical acclaim was overshadowed by overzealous government censorship, resulting in its subsequent banning for its messages and scenes of guerrilla warfare. The Deers held a mirror to the face of 1970s Iran, and its final scenes, in retrospect, can be seen as prophetic depiction of the months that would follow the Cinema Rex tragedy.

The Deers touched a societal nerve when it was released in 1974. Kimai’s film tells the tale of two old school friends, Ghodrat (Faramarz Gharibian) and ‘Seyyed’ (Behrouz Vossoughi), who are reunited as adults when the former seeks refuge from the police. Ghodrat is a wanted ‘professional thief’, and Seyyed a drug addict fuelling his heroin use with the pittance he earns working at the local theatre. The ball and chain of his prison sentence have maintained their grip as Seyyed’s attempts to re-establish himself are thwarted by poverty and lack of opportunity. Although both Ghodrat and Seyyed are pleased to see each other, they are deeply disappointed by their circumstances; and, in a shootout between Ghodrat and the police at the end of the film, the two both die as Seyyed refuses to leave his friend’s side.

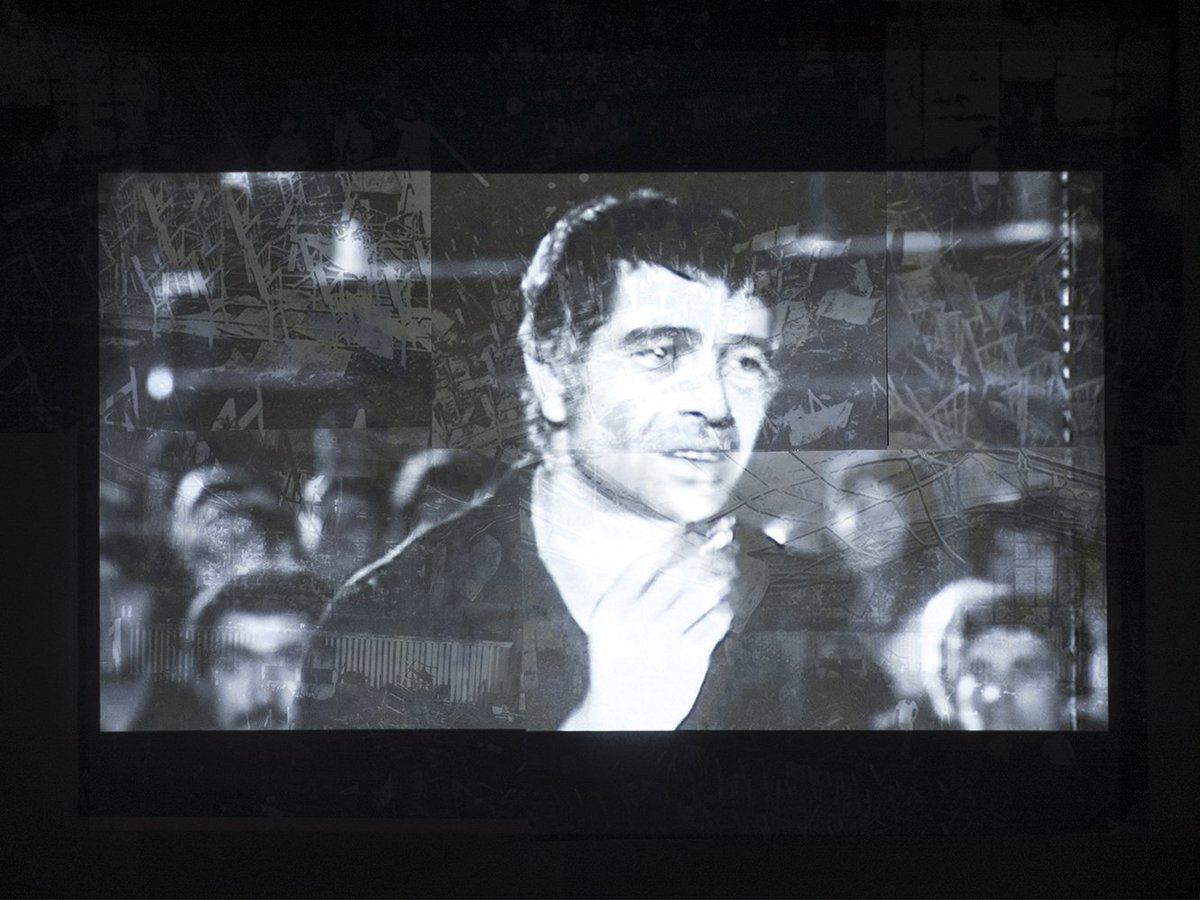

The Unity of Time and Place, Bakhshi’s current exhibition at London’s Narrative Projects (for which he was denied a UK visa), revolves around the arson attack. The pertinent and politically neutral installation, from which the exhibition derives its name, provokes discussions about the roles of artists in addressing social issues. Audiences are treated to a cinematic experience, much like the victims of the attack: the rooms, containing rows of weathered theatre seats, are lit only by film projections. The exhibition features two silent video montages, the first providing content: early scenes from The Deers have been superimposed onto images of chaos and cinders in the aftermath of the Cinema Rex attack. The second presents a silent interview with Kimai, who was asked by Bakhshi to respond to the attack and reports of the 400 unconfirmed deaths. Kimiai’s face immediately becomes contorted; his eyes are teary and unable to focus on even the camera. He had initially provided a response, but Bakhshi erased this as the director later decided that he did not want to issue a reply on film.

Masoud Kimiai (courtesy Narrative Projects)

‘Mahmoud’s work is always quite challenging, and he always tries to raise difficult questions’, says Narratives Project founder Daria Kirsanova about the artist. Bakhshi refuses to label himself as a political artist as he believes societal issues and art naturally intersect; but at the same time, politics has influenced him for as long as he can remember. ‘The type of art I saw as a child was mostly propaganda art or the type that mostly reflected Russian or leftist art’, he says. ‘What I started with was also influenced by them and the atmosphere [in Iran]’.

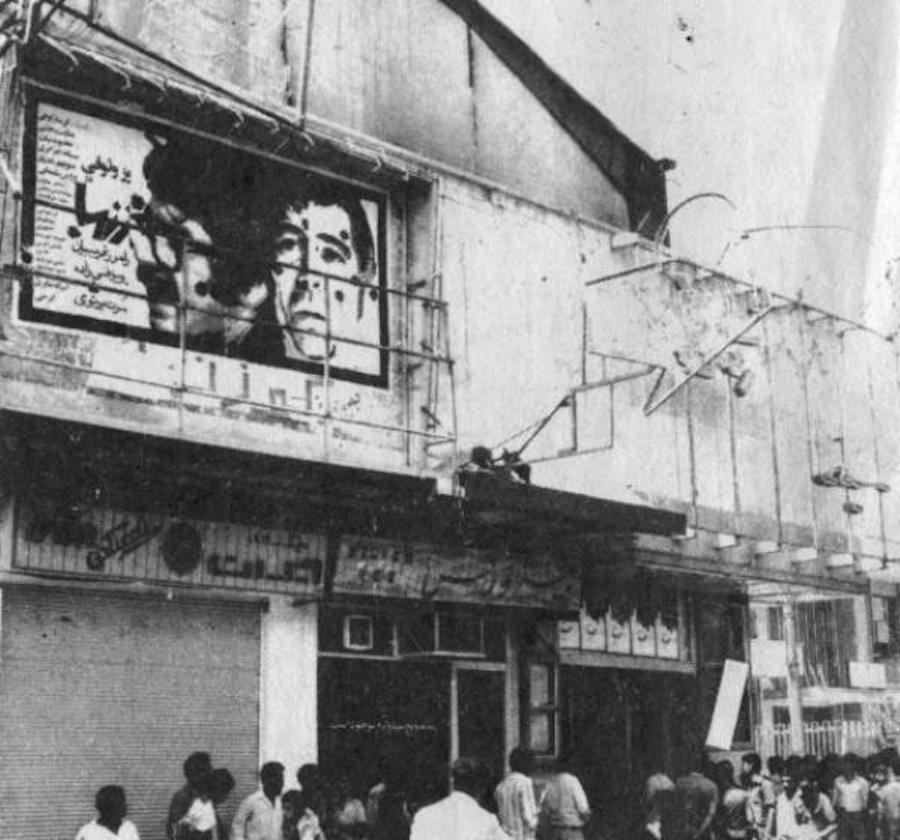

The Cinema Rex incident, a key moment in recent Iranian history, has had a lasting effect, its burning having remained in the public consciousness long after the fact

Bakhshi chose to address the Cinema Rex incident in his work because of its consistent presence (as well as that of film in general) in his childhood. ‘Right after the Revolution, they were showing films everywhere, even in the mosques’, remembers Bakhshi. ‘Once, they showed a documentary film about Chile and [Salvador] Allende in a mosque; it was a very weird experience, watching such leftist work there.’ Upon researching the tragedy, Bakhshi discovered the almost too convenient date (i.e. August 19) shared by it and the 1953 CIA-staged coup d’état that ousted democratically elected Prime Minister Dr. Mohammad Mossadegh. There is also a relationship to Abadan, the site of the tragedy, as Mossadegh had nationalised Iran’s oil industry two years earlier in 1951.

Behrouz Vossoughi (courtesy Narrative Projects)

Furthermore, 25 years after the coup, the Shah declared the 19th of August a day of festivities in celebration of what he called a national uprising. Kirsanova, also an art historian and theorist, confirms that The Deers played a part in influencing the uprisings in society, and, ‘ultimately, the Revolution … It’s an absolute direct link,’ she says, ‘that is very difficult to find in art history anywhere else’. Moreover, Bakhshi chose the title The Unity of Time and Place because, despite the links between the Cinema Rex incident and the 1953 coup d’état, he believes his message and art transcend both time and place. The Cinema Rex incident, a key moment in recent Iranian history, has had a lasting effect, its burning having remained in the public consciousness long after the fact.

Bakhshi sometimes sees himself as a documentary maker, an archivist whose work future generations will discover. In Iran, cinema and literature have played a greater and more influential role in the public than contemporary art, but the artist doesn’t believe that for this reason he must defer to more accessible methods of self-expression. According to Kirsanova, because of the relatively smaller audience for contemporary art in Iran, there is less scrutiny involved, resulting in what she sees as greater freedom. As this current exhibition does not (overtly, at least) push any red buttons in the sense that the crime has not been attributed to any particular party, Bakhshi hopes to one day show it in Iran.

Abadan’s Cinema Rex after the incident

Ought Kimiai apologise for creating a film inextricably linked to a catastrophic chain of events? As Bakhshi’s work suggests, artists are byproducts of the societies they live in. He says that all forms of art are important, and just because some claim that various ones provide ‘cheap shots’ at gaining recognition, in that they address popular issues, they are no less valuable. As well, although artists may be heedless of questions of ethics and influence in the creative process, Bakhshi’s The Unity of Time and Place suggests that they should perhaps consider the potential side-effects of their work. Indeed, some artists may be unaware of the power they unconsciously exercise in society.

‘The Unity of Time and Place’ runs through March 11, 2017 at London’s Narrative Projects.