‘There is no Palestinian defect’, Natche shows, and no ‘Other’

Spanish-Palestinian director Ahmad Natche’s film, Two Meters of this Land, is not set in Palestine – at least, not the Palestine that so many of us presume to know; for what do we usually expect from a film about this land that is everywhere and nowhere, on all our television screens and newspapers, though not in any tangible plot of territory it can comfortably call its own? What do we anticipate from this place that is real yet fictional, and familiar yet foreign, like the limp answer to a tragic riddle? We expect guns, blood, and wailing mothers, skull-piercing screams and crazed eyes, bodies writhing with rage, grief, and emotions yet to be identified; we expect creatures, whose husks resemble those of our own, but whose circumstances and the actions and reactions they engender make them wholly ‘other’ in relation to ourselves.

We don’t use words like ‘subhuman’ anymore, and terms such as ‘victim’ have been welcomed as euphemistic substitutes. Like criminals, whose characters are often defined by committed transgressions, victims can also be deformed into caricatures, defined solely by circumstances external to them, denied agency, stripped of the banalities of daily life that make them human. We can watch these victims on our television screens because their existence is so far removed from ours, and their experiences so alien to us that we can’t feel implicated, or experience the outrage provoked by a nervous empathy that can only, it seems, present itself when our reflections are threatened; when we see human debasing human, and come to fear for our own humanity – both in a physical and metaphysical sense. We worry that we too might one day be bombed, shot, or maimed by a fellow human, or arguably worse, that we might one day do the same to others. And what is a human being? A loose aggregate of behaviours that are, for the most part, universally familiar, comforting in their ordinariness, and gratifying in their mundaneness – a kind of meta-heritage of our troubled species that keeps us relatively in check.

Normally, we expect a movie about Palestine to show us individuals consumed by victimhood or criminality, their lives empty of anything we can see ourselves in. We expect to become enveloped in images so vicious that they paradoxically blanket us in the comforting falsity that what is happening ‘over there’ must be the result of abnormalities and deviances from the human norm, and spare us the guilt that accompanies passive awareness by convincing us that the situation, no matter how tragic it may be, simply cannot be helped.

A still from Two Metres of this Land

Natche’s film is a welcome disappointment. It brings the minutiae of daily life to the forefront, preventing audiences from establishing that comfortable ‘distance’ between themselves and the Palestinians on screen. Set on a summer evening in Ramallah, it is essentially, a film about nothing – or not much, at least. Two Meters of this Land follows a group of youths as they plan an outdoor music concert. Non-professional actors from Ramallah and Jerusalem play the roles of journalists, technicians, dancers, and musicians preparing for the performance and engaging in idle chitchat. The conflict forces itself in through, for example, a brief conversation about the inability of West Bank civilians to travel to Jerusalem, but is prevented from interrupting the cast as they assert their humanity through an insistence on engaging in ‘normal’ activities, despite their extraordinary circumstances.

The film opens with a Palestinian TV producer guiding a French colleague through a series of black and white photographs from the Palestinian revolution, introducing the Palestinian ‘other’: militarised, battle-hardened, ever serious. Natche then shifts to the teenagers from the El Funoun dance troupe gossiping and stretching, an awkward journalism student trying hard to be taken seriously by festival staff, a technician attempting to engage a Japanese photographer in conversation, charmingly maneuvering his way through her broken Arabic, and a number of others. The film lacks a cohesive plot; potential narratives are introduced, but never pursued. Instead, Natche offers small, simple glimpses into a day in the lives of a handful of Ramallah’s residents, as they steadfastly carry on with things despite their situation.

‘Two metres of this land are enough for now’, wrote the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish, ‘[and] a meter and seventy five centimetres are enough for me. The rest is for a chaos of brilliant flowers to slowly soak up my body’

The film features what are, in essence, ‘boring’ conversations, which remind us of the many trivial things we say and that are said to us on a daily basis. In the backdrop of these ordinary discussions and activities, however, can be seen a wall – an imposing concrete reminder that what we perfunctorily engage in every day, Palestinians must struggle for, that they have to constantly reconstruct after every demolition the normalcy we take for granted; that the humanity we assume the moment we leave the womb, placenta, umbilical cord, and all, is in fact precarious. It is capable of being undermined, broken down, and even annihilated. It is in need of fervent protection. We could have been born in Palestine, we realise; we could be preparing for a music festival. We could be attempting to group up ‘normally’ in Ramallah despite walls, checkpoints, and settlers. There is no Palestinian ‘defect’, Natche shows, and there is no ‘other’; there is merely a conditioned situation produced by an aggregate of individuals, with the potential to be undone or at least, redressed by another differently-minded group of individuals.

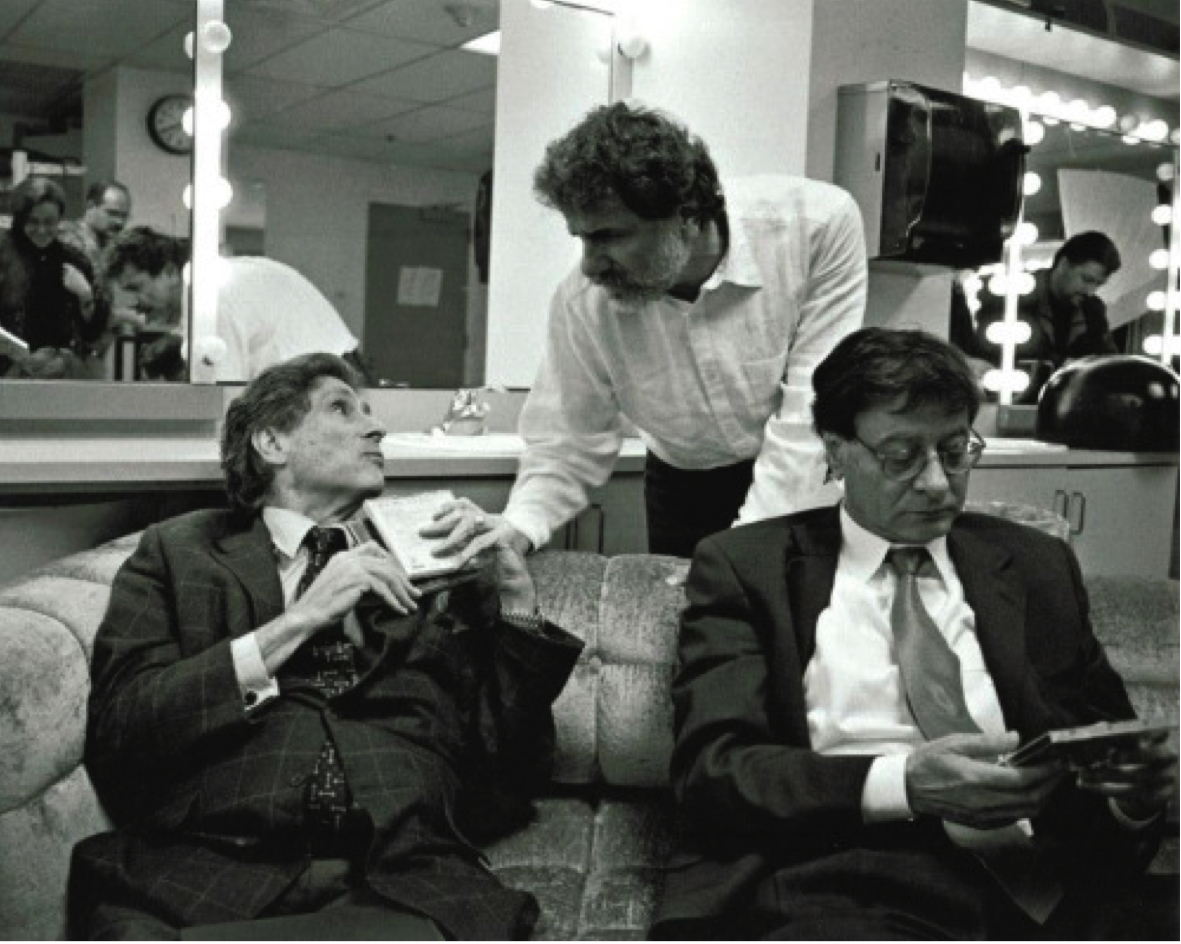

L-R: Edward Said, Marcel Khalife, and Mahmoud Darwish

‘Two metres of this land are enough for now’, wrote the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish, ‘[and] a meter and seventy five centimetres are enough for me. The rest is for a chaos of brilliant flowers to slowly soak up my body’. Despite their trying circumstances, Palestinians - as Natche’s film implicitly asserts - refuse to forget who they are, and to abandon their identity and humanity. On the small slice of land they still, to a limited degree, possess, they carry out their ‘Palestinianness’ daily, paying homage to bygone villages buried beneath settlements by singing their songs, dancing their dances, and reciting their poetry. At one point during the film, a performer rehearses a speech most likely intended to serve as the festival’s opener. She describes the event as more than a mere form of entertainment. In Palestine, she explains, such an occasion is inherently political, because a key aspect of daily resistance is the preservation of national identity; for the Palestinian struggle cannot persevere without a palpable Palestine to work towards. So long as oral narratives are passed on through a ritualistic stitching of aging mouths to youthful ears, the personalities of erased territories are continuously embodied by their descendants, and Palestine is faithfully reincarnated in a variety of forms in refugee camps and diaspora communities, as Natche’s film shows, Palestine will continue to develop and mature, despite its shrinking corporeal form; it will insist on its existence, refusing to be forgotten.

Despite their humiliation, loss of dignity, and the weight upon their backs, Palestinians have been keeping up a resistance – in a non-traditional sense of the word – through their music and heritage festivals, poets and scholars, artists and filmmakers, creative agriculturalists and ingenious entrepreneurs, and the stories of their grandparents. They continue to survive, not as passive victims, but as dynamic human beings in the face of an adversity that has threatened, yet failed to abolish their Palestine.