Works from a new generation of Lebanese artists on view in Madrid

After the Civil War, Lebanon became one of the most prolific places of artistic production in the Middle East, boasting names such as Lamia Joreige, Akram Zaatari, Khalil Joreige, Joanna Hadjithomas, Walid Raad, and Ziad Antar. Today, a new generation of artists is developing an innovative, conceptual language focused on the present rather than a lost past, ambiguously dealing with a wide range of topics and leaving ample space for interpretation and engagement. Currently on view at the Casa Árabe in Madrid until November, when it will travel to Cordoba, I Spy with My Little Eye … A New Generation of Beirut Artists, curated by Sam Bardaouil and Till Fellrath, brings together the work of this new generation of artists, each of whose pieces are somehow associated with Beirut, in one way or another.

The participating artists hail from different parts of the world, evidence of the fact that their connection with the Lebanese capital is not necessarily one of citizenship. In some cases, the artists live or have lived there, own a studio there, or simply look to Beirut as a source of inspiration. The fact that these ‘Beirut artists’ are not necessarily Lebanese citizens introduces a new conception of identity detached from geographical origins or bonds, which takes into account other phenomena. As Fellrath explained during a tour of the exhibition, one of the shared objectives of this new wave of artists is transcending the language and conflict-centred proposals of the preceding postwar generation. Instead of a collective process of archiving, preserving memories, and reconstructing the past, this generation is more individualistic, highlighting the significance of the present, the value of the intimate, the expressive possibilities of the material, and the shift in the conception and definition of art.

The reconsideration of the Self, the present, and intimacy are reflected in pieces such as Mirna Bamieh’s A Brief Commentary on Almost Everything, a slow-motion self-portrait video of the artist yawning. Such an ordinary and quotidian gesture is transformed into an epic deconstructed instant that catches visitors’ eyes, and in which, as the catalogue mentions, ‘the most intricate of details assumes the monumentality associated with grand gestures’. The casual arrangement of various works reveals the aforementioned celebration of immediacy, a praise of the ‘here and now’ character of the process of artistic creation, presented as something as valuable and displayable as the finished product itself. In addition, the inclusion of manipulated ordinary objects also leads to an interesting process of self-recognition while questioning where the boundary separating the ordinary from the extraordinary, the private from the public, and art and ‘non-art’ can be drawn. Pascal Hachem’s Mirror Mirror, in which a pair of tied shoes separated by a mirror reflect the spectator, is an example, as are the scattered telephones and the hybrid lamp of Stéphanie Saadé’s Let it Ring, wherein a blinding light hangs from a chandelier, bringing together the past and the present in a subverted representation of the known.

The unfinished nature of works such as Tala Worrell’s canvases, one of them not even hanging but instead exhibited alongside some of her paint cans, calls for audience intervention. The playful engagement with the ‘ever being and becoming’ nature of some pieces suddenly transforms the exhibition into a game, and the passive witnessing into a tactile meeting. This is what happens with Lara Tabet’s The Reeds, a group of unframed photographs taken in a sexual cruising ground in Beirut and kept in a box. The box is placed on a table with a lamp, inviting visitors to take the pictures out of it and discover that most of them are blurred. Only by doing so can one try to interpret what is actually portrayed in each photo.

Pages from Lara Tabet’s The Reeds (courtesy Oodee Books and the Village Bookstore)

Visitors’ interactions and the metamorphosis and reenactment of out-of-context, yet still-recognisable pieces stimulate a rediscovery of the known, thus unveiling a different way of seeing what has been seen many times before. It is precisely this emphasis on the importance of seeing what remains hidden or uncertain that the title of the exhibition refers to. I Spy with My Little Eye is the initial sentence of a children’s game that consists of secretly choosing an object, giving a clue about it, and letting other participants guess what one is thinking about. In Madrid, the title has been translated to Juego de Pistas, which literally means ‘game of clues’, but in reality refers to the veo veo game. Comically, even the catalogue’s leaflet seems to resemble an instruction manual.

This generation is more individualistic, highlighting the significance of the present, the value of the intimate, the expressive possibilities of the material, and the shift in the conception and definition of art

The ingenious and innocent childlike way of thinking has been coupled with viewers’ ability to see the smallest and most imperceptible of things, to discover what is apparent, yet obscured. The title, on one hand, emphasises the playful and interactive character of the exhibition as well as the role the works play as clues of the unseen. On the other hand, it reveals a new generation of artists as the representatives of a still-emerging language presented in its early stages. Behind the game, however, lie a wide number of discreetly insinuated concerns of absolute topicality. Pascal Hachem tackles the complex and ever-changing definition of self-identity and its construction in Non-Essentialism, in which a piece of Lebanese bread is placed over a mirror revealing the inscription, ‘Made in China’ on its back. The confrontation of a staple Lebanese food with its Chinese precedence leads one to question what one always thought was, but might not be anymore. Identity in Hachem’s piece is suddenly revealed as a rich miscegenation nurtured through a coexistence and dialogue with the Other.

Pascal Hachem - Non-Essentialism (courtesy The Mosaic Rooms)

It is the remapping of the Self and the configuration of a hybrid identity, simultaneously unique and universal as a result of exile and displacement, that George Awde’s photographs of young Syrian refugees in Beirut represent. Their defiant look, their uncertain, precarious and idle lives, and the forced transition from youth to adulthood are brought to the foreground. The identity of his subjects becomes a tricky, ambiguous field where the senses of strangeness, loss, nostalgia, and a need of belonging somewhere are blended with a permanent self-criticism and continual adaptation to new circumstances. It might be worth mentioning that one of the photographs has been hanged at such a low height that it forces viewers to look down, perhaps in an attempt to place it at the eye level of a child instead of an adult. According to Fellrath, Awde went back to Beirut to photograph the same children years later.

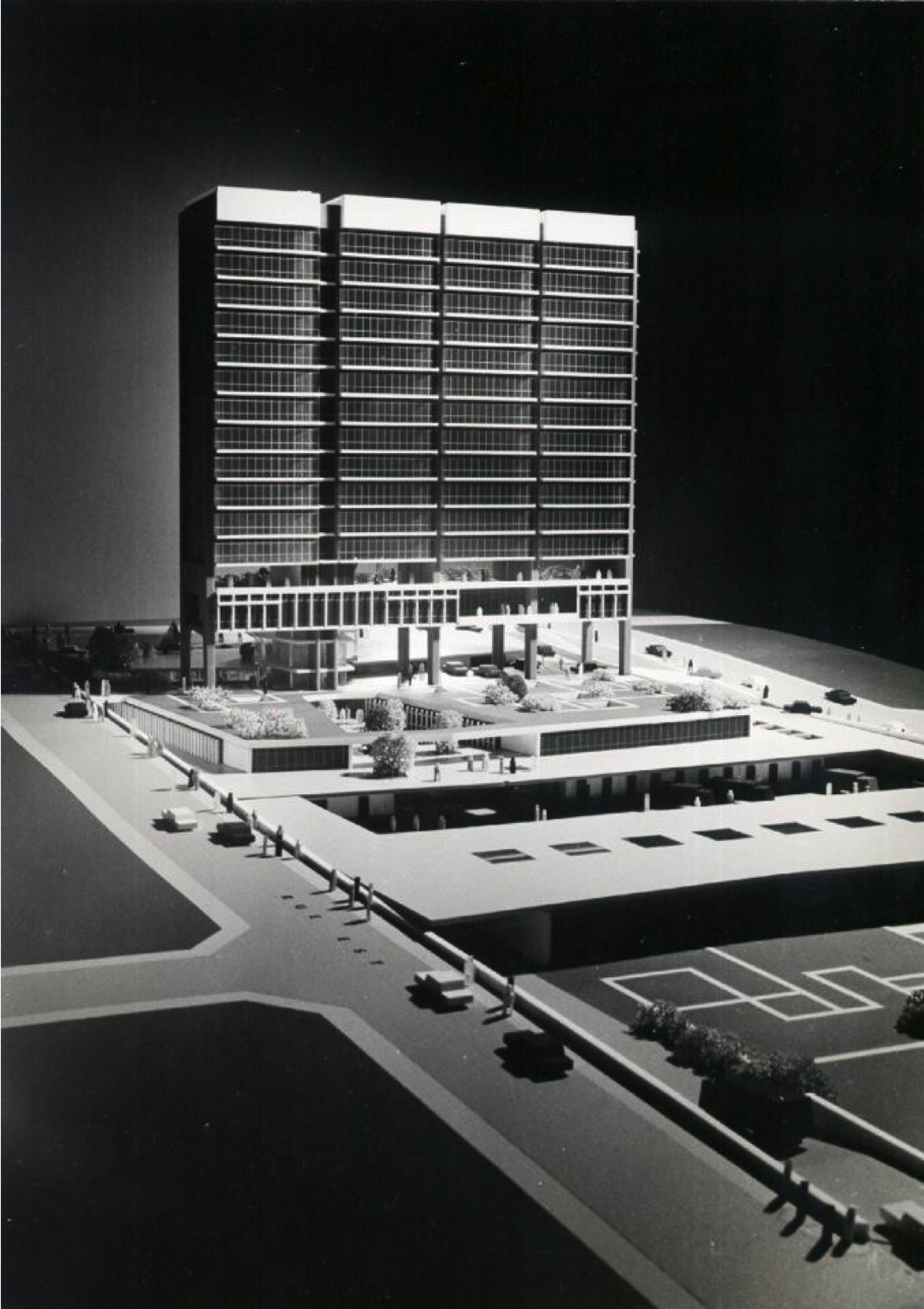

Awde’s works are not innocent and neutral representations of the refugees, as they contain a certain political and critical bent, and are not the only bitter references to contemporary issues. Siska’s video, recorded with a Super 8 camera, shows the poorly-preserved interior of Beirut’s Electricité du Liban building (Lebanese Electricity), allowing the artist to censure the corruption of Beirut’s ruling powers as well as the electrical problems the city faces. This is also the case with Aya Haidar’s Return to Sender, an installation comprised of a series of stamped United Nations envelopes posted to the Middle East, pinned on a corkboard and manipulated by the artist. By erasing and rewriting the messages on paper, she subverts the original meaning, satirically criticising the character of the UN while dealing with issues related to boundaries, displacement, and memory.

A still from Siska’s E.D.L. (courtesy Shubbak)

Nour Bishouty also works with such themes in Instead of a Resolution: Inside/Outside, an installation of rubber imprints of stamp marks discovered in a woman’s passport. This piece can be seen as a way of giving shape to memories, of tracing a person’s steps and journeys all over the world throughout their life, paradoxically freezing the dynamics of migration and travel. It is interesting to see how the artist transforms the memories of numerous trips into rubber, ‘preserving the un-preservable … and bridging the material image with the intangible one’, as the exhibition catalogue notes.

Caline Aoun’s installation, on the other hand, presents a suggestive and more intimate way of displaying and preserving her memories, associated with her Lebanon studio. In One Thousand Pine Needles, a mountain of copper casts of pine leaves is spread on the floor as a reference to the landscape surrounding the artist’s studio in the Lebanese countryside. The ephemeral and somehow worthless existence of these needles is challenged through its new long-lasting and precious character, and it is the material used in this work what changes the whole significance of the needles, configuring new connotations and assuming almost all the semantic weight.

Caline Aoun - One Thousand Pine Needles (courtesy the artist and Grey Noise gallery)

Joe Namy’s A Third Half Step and Joseph Charbel H. Boutros’ Let it Ring are also commemorations, in these cases of past artistic happenings or actions. The performances, whose nature is ephemeral, immediate, and of the ‘here and now’, are somehow preserved and recorded through the partial reproduction of their spatial and temporal circumstances in the exhibition. The first work consists of a video presenting a dabke dancer inside a richly-decorated Arab house and its black platform, where the traditional Levantine dance was once performed and where traces of its steps can still be followed. In Boutros’ performance, three different phone calls with seven-second intervals between each were made to telephones in different continents, whose locations formed a perfect, invisible, equilateral triangle reproduced in the exhibition.

I Spy with My Little Eye … presents a complex network of challenges, connotations, and overlaid topics that reveal a unique and genuine vision, as well as a rediscovery of the world from a different perspective. The exhibition also brings a sample of a rich culture being forged in the Middle East scarcely known in Spain, encouraging audiences to look again and see the still-unnoticed.

Y tú, ¿qué ves? Let the games begin.

‘I Spy with My Little Eye …’ runs through November 22 at the Casa Árabe in Madrid.

Cover image: George Awde - Untitled (detail; courtesy the artist and the East Wing gallery).