From the fringes of society to global sensations - Yemenite Jews and the Mizrahim of Israel

For decades, Yemenite Jews have been amongst the ‘underdogs’ of Israeli society. They have stood at the bottom of the social ladder, and have had to abandon many aspects of their culture and traditions in order to integrate. It was their culture, however – their music in particular – that changed the course of my life for good, and set me on a search for my own identity.

The Boy in the Abaya

I have always been a child of challenges, always struggling to find my own identity. This eternal questioning began at an early age. After watching Disney’s Aladdin at the age of eight, everything changed. From that moment, I became completely captivated by the Middle East; and, starting then, I began to wear an abaya at home. In my dreams, I was Princess Jasmine.

Immediately, my fascination for an incomprehensible, mysterious world set me apart from my family; they didn’t understand me, and I couldn’t understand them. When talking about the Middle East, I often heard remarks about barbarism and terrorism, and not much has changed. But, of course, those were some of the last things I would think of, especially as a little boy in an abaya. The heavier my discussions with my family members became, the further I distanced myself from them. In my opinion, they were ignorant and confused by fear, while I was angry and indignant. Slowly, I flew away from them on my magic carpet.

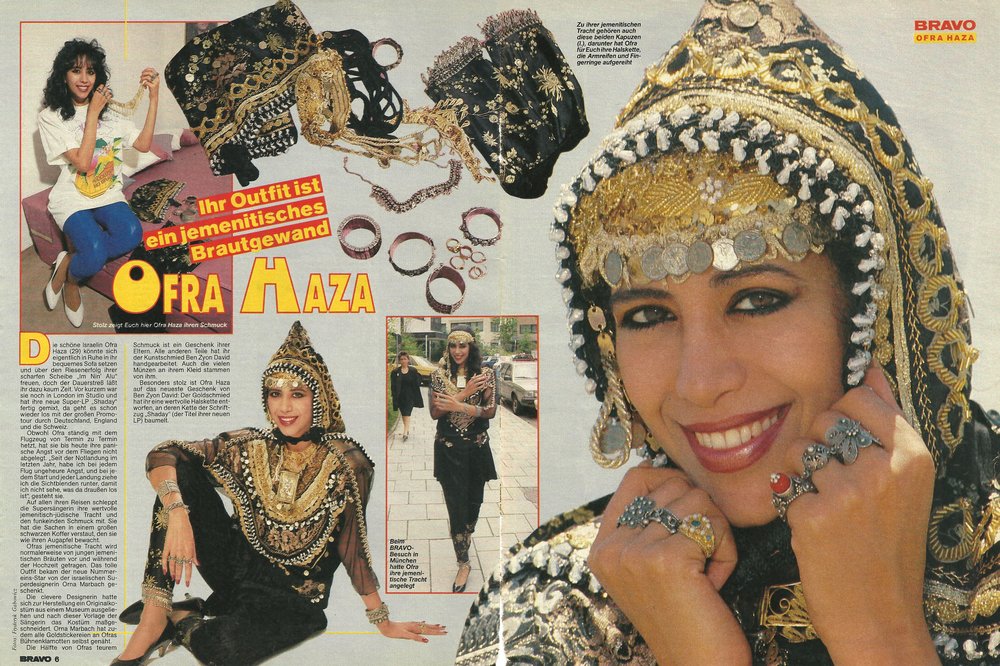

An Ofra Haza style guide in Bravo, a German magazine (photo by Fryderyk Gabowicz

To further ‘nourish’ the impact of the situation, I began listening to the Yemenite-Israeli pop singer Ofra Haza. A few years back, she had released the single Im Nin’ Alu, [her] international breakthrough that sold over three million copies worldwide. In various countries, the remixed version reached the top ten charts, and in several instances, number one spots. Years after the release of her debut album in 1974, Haza decided to return to her Yemenite roots. With poems written by Rabbi Shalom Shabazi, she released Yemenite Songs, a record full of traditional chants, in 1984. Looking back, one can realise the significance of the transformation of a Yemenite girl who left the slums of Hatikva in Tel Aviv to become Israel’s ‘Queen of Pop’.

It wasn’t Haza that I idolised, however, but the Yemenite-Israeli club diva Dana International; I felt I could identify with her. To me, she represented the concept of multiculturalism, and, perhaps, the celebration of a lifestyle in a mixed-yet-complex region wherein different cultures and sexual orientations come together. Her early career is especially interesting to me. In his article Sa’ida Sultana / Danna International: Transgender Pop and the Polysemoitics of Sex, Nation, and Ethnicity on the Israeli-Egyptian Border, anthropologist Ted Swedenburg investigated the effect of Dana’s Arabic-language songs, such as Sa’ida Sultana, Danna International, and her cover of Samar-Mar. It is estimated that millions of copies were sold in black markets in countries like Egypt and Jordan. After it became known that Dana was in fact an Israeli singer singing in an Egyptian dialect, she was looked at by many as a spy trying to take advantage of a ‘naïve’ and ‘vulnerable’ Egyptian youth. Accordingly, the Egyptian authorities took several measures to prevent the sale of a so-called ‘prostitution tape’, but without success; the youth loved Dana’s sultry voice and risqué lyrics too much.

Listening to Dana’s diverse repertoire, I reflected on issues surrounding discrimination, migration, and multiculturalism, which all became processes I wanted to better understand; I wanted to be a part of this worldly diversity. It was a difficult task to find a balance between the Netherlands, Israel, and the Arab world, though. During my adolescent years, the struggle became even harder. These years were, without a doubt, the most difficult when it came to finding an identity and a place in a society wherein the fear of the Arab world was continuously present, and a hatred of Israel was on the rise. My search resulted in me becoming a complicated person, and I felt at one point that I didn’t belong to any particular group.

1948 and All That

Zionism is considered one of the most successful national movements in history. Though originally a secular ideology, it soon became clear that the founding of the Jewish state was in line with a scenario proposed by Theodor Herzl. In 1896, the self-proclaimed atheist wrote the book Der Judenstaat (The Jewish State), in which, through a rational analysis, he outlined a detailed and practical action plan. Herzl developed a social system that many might today attribute to a welfare state. His idealistic beliefs and vision were not confined to one particular population or group, although his intentions were unclear to many of his followers. Even after the founding of the Jewish state in 1948, ideologies amongst various Zionist groups differed, and no single one was decisive by itself.

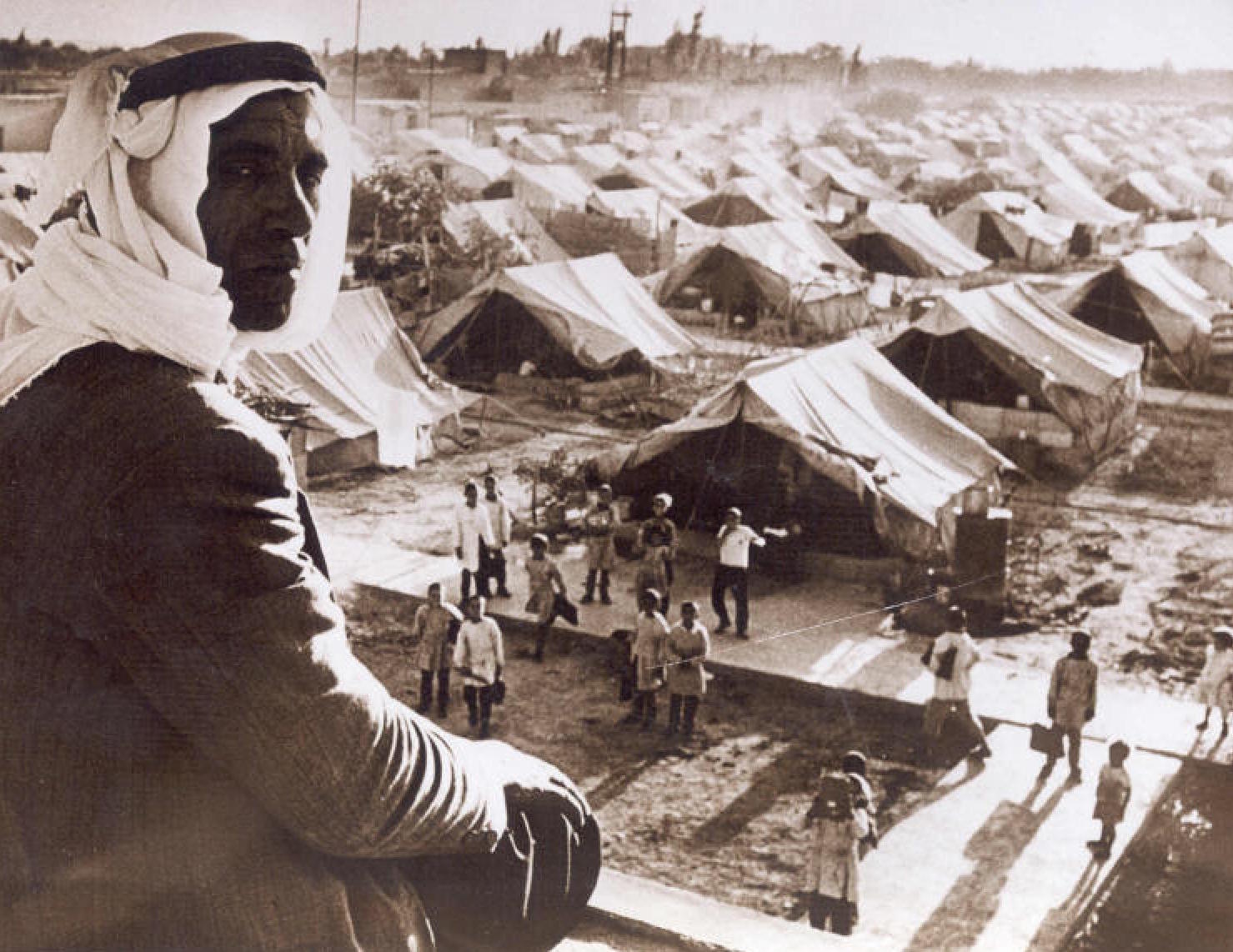

Palestinian exiles leaving their homeland following the Nakba (Catastrophe) of 1948

When Israel was founded, it was emphatically proclaimed that within the Jewish state, there would be no discrimination on the grounds of race, religion, or gender. Nevertheless, the issue of Arab Israelis became problematic and unfavourable in the eyes of many. While they had been nominally granted civil rights in name, and there hadn’t been any laws passed against Palestinians, the Arab community was nonetheless barred from expressing itself politically. The German-American philosopher Hannah Arendt rejected what she saw as Herzl’s colonial approach, and, not sharing an affinity for the politics of a bygone era, opted instead for a Jewish policy that was practical rather than cultural. After the founding of the Jewish state in 1948, Arendt concluded that without any agreement with Israel’s Arabs, the whole enterprise would be doomed to fail. In her 1945 essay Zionism Reconsidered, she noted how socialist Zionists only paid attention to their national purpose without giving a thought to the Palestinians. It was a revisionist Zionist ideology, she believed, based on a 19th century concept of a nation state as a model for Israel, which posed so high a threat. According to Arendt, this ideology fostered a racist chauvinism that tolerated the use of terrorism to create panic, and thus encouraged the Arabs to flee Israel. Arendt predicted that the Jewish state could potentially develop into a military ‘fortress’, and that the number of Arabs leaving the country would increase dramatically. Because the philosopher became increasingly skeptical about prospects for peace in the region, she pleaded for a bi-national solution in the case of Palestine.

A Palestinian refugee camp in Damascus in 1948

Historically speaking, the cultural heritage of the Arabs has been shared by Muslims, Christians, and Jews alike; but, with the rise of Zionism, there arose a distinction between the ‘Jew’ and the ‘Arab’, making it difficult for Jews of Arab descent to maintain and retain their identities. Typically, Arab and Eastern culture was seen by the ruling Ashkenazi elite as inferior and primitive, especially as many Middle Eastern Jews (referred to as Mizrahim) of Israel – Yemenites in particular – were poor and lived in the slums. What followed was a form, regarded by many, of cultural oppression, whereby Arabic and Mizrahi music were banned on Israeli radio for decades. As Danny Kaplan wrote in his article, Cyclic Interruptions – Popular Music on Israeli Radio in Times of Emergency, such programming was consistent, with the selection and timing of songs chosen to foster a sense of national identity.

The intense stigmatisation of Arab culture and the Arabic language, as well as developments that have forced Arab Jews to adopt Hebrew as their language reflect in many ways the story of my life

Radio stations, as Kaplan explained, were largely a national interest; but, with the invention of Philips cassettes in the early 70s and the development of ‘light Mizrahi’ (a genre influenced by both Arabic and Western pop music), there came a revolution. The production and distribution of the cassette allowed Yemenite-Israeli singers such as Zohar Argov, Haim Moshe, and Ahuva Ozeri to make their voices – and cultures – heard. Against all odds, Mizrahi music grew into a phenomenon, and today is regarded by many as ‘typical’ Israeli music.

Les Mizrhables

Despite their popularity in music, attitudes towards Mizrahim in Israel have remained virtually unchanged, and many young Israelis today feel that there is still much work to be done. Possibly as a sort of resistance, Arabic-influenced music saw another revival in 2015, with the advent and success of a new generation of Yemenite-Israeli musicians such as A-WA, Yemen Blues, and Shai Tsabari. In March of 2015, A-WA debuted with the single Habib Galbi (Dear of My Heart). This old and classic Yemenite folk song that originated in the Yemeni desert hundreds of years ago came to life again when three Yemenite sisters – Tair, Liron, and Tagel Haim – sent a demo tape to Tomer Yosef, lead singer of the Balkan Beat Box group. After Yosef turned the sisters’ demo into a catchy song, the video went viral and became the first Arabic-language song to top the Israeli charts, and today, it boasts nearly two million views worldwide. Yosef also produced the entire album (also titled Habib Galbi), which contains other traditional songs written by Yemenite women, many of whom were illiterate.

Even considering the various joint social and cultural achievements of Ashkenazi and Mizrahi Jews in Israel, Israeli society has largely remained deeply divided. The intense stigmatisation of Arab culture and the Arabic language, as well as developments that have forced Arab Jews to adopt Hebrew as their language reflect in many ways the story of my life. In a world where xenophobia is all the rage, the road to self-realisation has been a difficult and emotional one. During my life, I have not only suffered identity crises, but have also had to deal with loyalty issues. I began to live for myself, and became immune to the fear brought on by my environment; I simply could not afford to, any longer.

Suspended between often-hostile worlds, the urge persists in me to convince others when I am labelled or become the victim of their misconceptions. More than 20 years after watching Aladdin, it seems that nothing has changed. Still, I do not belong to any group; still, many people talk about the Middle East without even having an understanding of it. Many people look at me strangely, bombard me with their prejudices, and look at my fascination with the Arab world and the Middle East as a restriction, while I regard it as an enrichment. Yemenite-Israeli singers like Ofra Haza and Dana International have broadened my perspective, and expanded my vision. Through them, I learned to look at the world in a new and different way, and to become the cosmopolitan person I am today.

I am a lover, not a ‘traitor’.