Weaving stories with silver and stardust: Vartan Avakian in Beirut

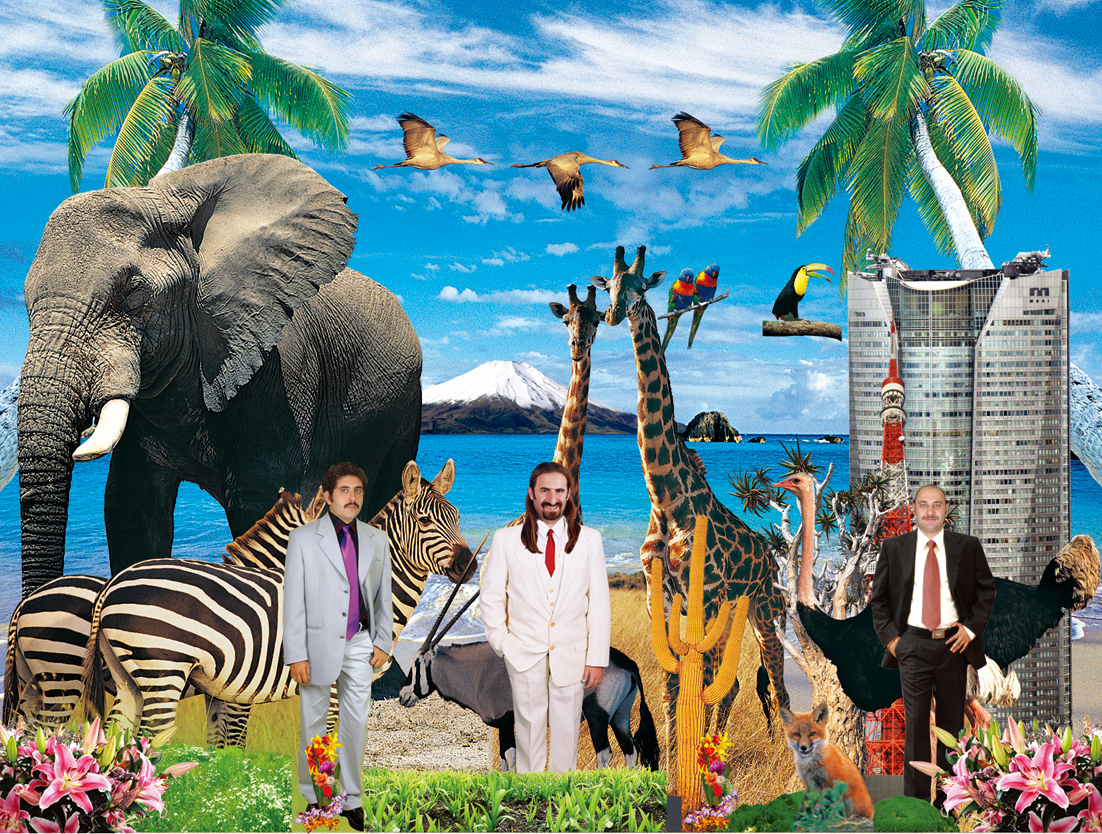

A pop artist is what Vartan Avakian is. Everywhere he goes, his research begins with an exploration of popular culture and the mundane that characterises the quotidian. In Japan, the artist playfully created mashrabiyas imitating the Quick Response codes that had excited Nippon’s youth at the time, and surprised hungry audiences by including an excerpt of abstract poetry where they expected to see flamboyant advertising instead. Avakian, of Armenian-Lebanese ancestry, has gone from excavating Lebanese audio-visual heritage and a number of B action films to mapping the ever-changing image of Beirut and the urban and political environment in Lebanon. The delightful buffoonery of his work reaches a peak when he recycles studio photographs from around the Arab world with Raed Yassin and Hatem Imam, two other independent Lebanese artists with whom he co-produces projects dealing with collective memory under the name of the trio’s collective, Atfal Ahdath.

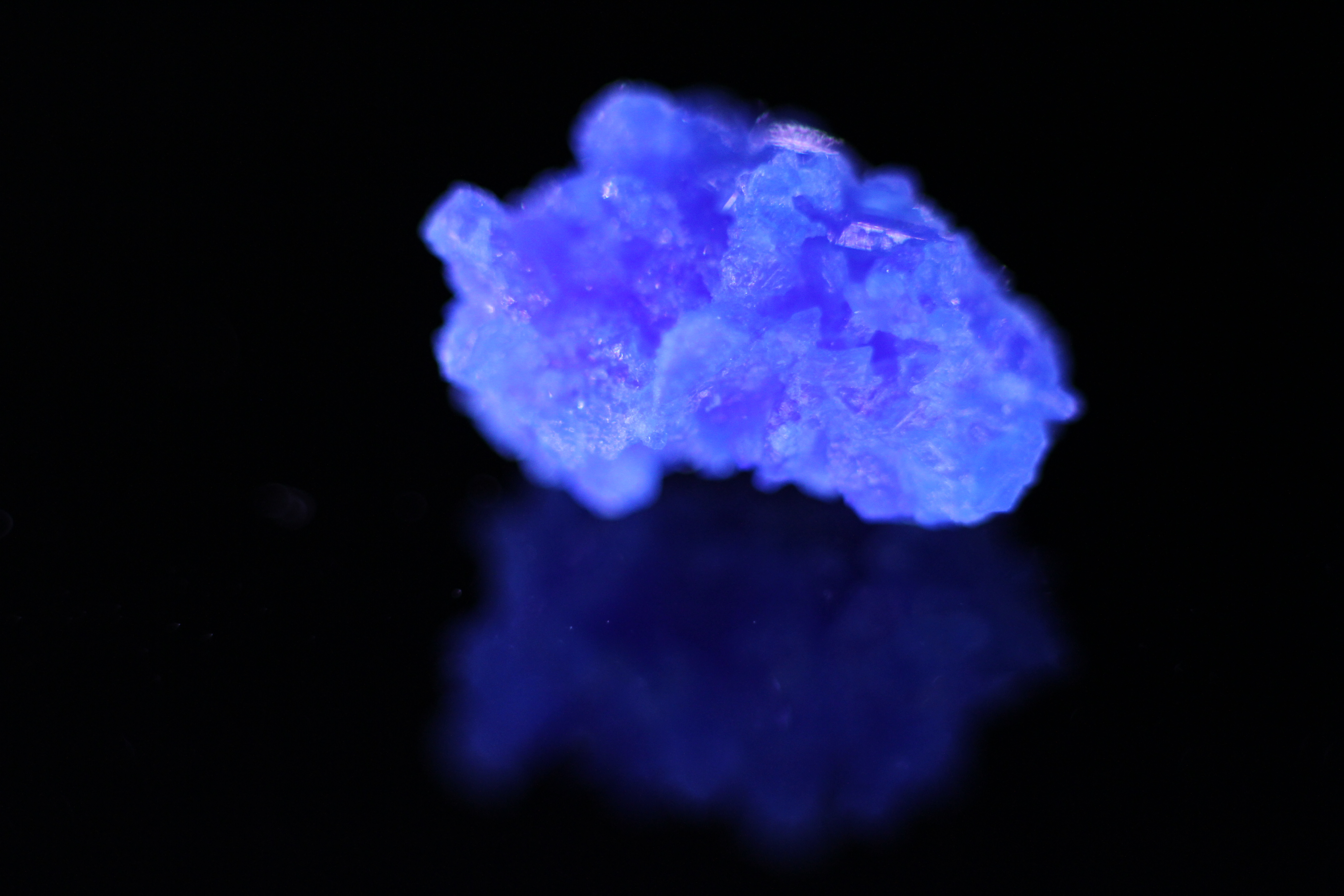

The result of another excavation, the work that he presented for his first solo exhibition in Beirut was more ‘serious’, as Avakian there flirted with science. It again had its origins in old photographs (found in Beirut’s Barakat building), but this time, the artist focused on their afterlife. Abandoned to dust in a building known by five different names – depending on how people like to remember it – the photographs became over the years a smorgasbord of grime. In addition to the active memory they retained, another one formed, thick and living, that Avakian chose to interpret through the prism of chemistry. By transforming into crystals the dust that amassed on their surface, he took audiences back to the formation of the Earth itself, when particles exposed to high temperatures and pressures formed into stones of various shapes and colours. Avakian’s stones stood on raw concrete pillars as tinted marvels of a few cubic centimetres in volume, floating in a pristine room; unobtrusive meteorites travelling through time, rather than space.

Atfal Ahdat - Take Me to This Place - I Want to Do the Memories (courtesy Vartan Avakian, Raed Yassin, and Hatem Imam)

The title Avakian gave to his collection of minerals at Beirut’s Marfa Gallery, Collapsing Clouds of Gas and Dust, resonated with a sentence used to introduce the [unrelated] exhibition, Under the Clouds, curated by João Ribas at the Serralves Museum of Contemporary Art in Portugal last summer: ‘in these ineffable clouds lies the phantasmagorical nature of our contemporary sublime [sic.]’. As a matter of fact, more than only geological excess, the crystals recounted the past 30 years of the Barakat building, whose story has been characterised by conflict and its aftermath that organised oblivion has chosen to erase from the history books of students. The crystals chronicled a lost heritage that local authorities prefer people to blame on speculation, rather than bombs. They recorded the various facets of disasters, and helped audiences grasp the immensity of memory when not restrained by the weight of collective memory.

Meticulously, Avakian gathered the micro-elements of Lebanon’s fragmented history. In a series of photographs entitled Suspended Silver, he scanned the silver particles collected in the debris surrounding the film, before enlarging and printing them on black backgrounds. The process resulted in minimalistic, monochromatic compositions, elegant explosions of scattered powder leaving viewers at the edge of the impalpable. An irony of time and progress, the light-sensitive surfaces on which memories used to be revealed had lost traces of their original content, but were still imbued with the purpose of telling stories. The scaleless patterns became what Avakian called ‘inscriptions in their own right’, in which the infinitely small melded with the infinitely large and allowed the imaginary to step into a heavy reality.

Beirut’s Barakat building

Though – given the relatively repetitive nature of the works – the exhibition could have been viewed in around five minutes, it invited audiences to decipher its coded abstraction. The two series of works evoked abyssal skies and the unidentified objects inhabiting them. Ultimately, Avakian paid tribute to the inherent aesthetics of nature that human creativity, perhaps, has never surpassed; dust has accumulated through the absence of man and his remains. The human element in both series intervened in a conceptual way; the hands and mind served as mere vectors for a theory of existing forms – or, what the British women’s rights activist Annie Besant called ‘thought forms’. According to Besant, these – which Avakian triggered – are:

Embodied entities of both the real world and the imaginal [sic.] realm, visible and vibrating manifestations of what is generally invisible that can be apprehended in intense states of awareness, meditation, affect [sic.], and desire.

From the Collapsing Clouds of Gas and Dust series (courtesy the artist and Kalfayan Gallery)

Dust is soil / Dust is pollen / Dust is burnt meteorite particles / Dust is also hair, tears, blood, sweat and shed skin cells / Sites of history are heavy with dust / They attract us with the weight of this dust: this debris. This poetic introduction featured in the exhibition’s accompanying booklet served as an abecedary that helped unfold stories. Just as the Rosetta Stone provided the key to a modern understanding of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, the tiny stones commissioned by Avakian also led to a renewed understanding of language as art. An act of transformation, art can allow for something usually treated as being unworthy of serious consideration to become monumental. The flawless display of the works aroused the same interest as does a laboratory or cabinet of curiosities. The gallery became a study room gathering disparate, extraordinary, and instructive objects, a chamber of wonders offering a space of reflection allowing for the study of art and the observation of surprising creations of nature and unusual souvenirs.

[Avakian’s crystals] recorded the various facets of disasters, and helped audiences grasp the immensity of memory when not restrained by the weight of collective memory

From the Suspended Silver series (courtesy the artist and Kalfayan Gallery)

The found photographs were nowhere to be seen in their original forms; and they didn’t need to be. The layers that time had applied to their fragile surfaces had given shape to other astonishing landscapes. Solidified by humidity, the dust formed on the photographs created tiny granular craters, cracks in canyons revealing the brightness of what could be faded smiles, pyramidal mountains, and dunes and ravines in a sea of black sands. When uncovered, they revealed portraits from another era ahead of its time, and poems written from a loving photographer to his beloved. In a few lines that bitterly echoed the blindness that has engulfed so much of society today, the outline of a sheep could also be found within them. That, however, is another story.

‘Collapsing Clouds of Gas and Dust’ ran between October 22 – December 12, 2015 at Beirut’s Marfa Gallery.