From ‘Scenes and Types’ to Shehrazade and El Sham: studio photography in the Arab world

The value of a photograph – its principle charm, at least – is its infallible truthfulness. We may have long revelled in the poetry of the East; but this work enables us to look, as it were, upon its realities1.

So said the 19th century Orientalist, Sophia Poole. Poole’s perception of photography’s unique ‘claim to truth’2 was widely held by early photographers from the West, to whom the colonial realms of the Middle East provided their principal training grounds3. In her seminal book On Photography, Susan Sontag challenged the ‘presumption of veracity’ that had long been associated with photography, arguing that photographs are ‘as much an interpretation of the world as paintings and drawings’4. But to what extent is this appreciated today? Whilst many claim to have developed their understanding of the art from the idea of a visualised ‘truth’ to a moment of representation, people continue to search for realities within photographs, particularly within archives. How useful is it to mine such documents for historical and social ‘realities’? Can these momentary representations of individuals, as captured in a photograph, be extrapolated to speak of an entire society, time, or people?

An early 20th century French Scenes and Types postcard of an Algerian girl published by Lehnert and Landrock

As European photographers travelled across the Middle East in the late 19th century, the practice of photography began to take root, with studios popping up in many major cities including Istanbul, Cairo, Alexandria, Beirut, and Jerusalem5. Most of these studios catered to European tastes that demanded local ‘types’ and genre scenes with a ‘distinctive ethos of emptiness, timelessness, or backwardness,’ maintains Lucie Ryzova, ‘[that] responded to Europe’s own self-perception as the discoverer, the conqueror, and the civiliser’. However, a local market for studio portraiture naturally developed and rapidly spread. These early Middle Eastern photographers were pioneers in their field, but relatively unknown or under-studied until this century, wherein the age of ‘archive fever’ has uncovered such long-hidden or forgotten archives. Today, archives of portrait photographs have been reinvigorated for contemporary audiences, such as those of newly-acclaimed American ‘masters’ Mike Disfarmer and E.J. Bellocq.

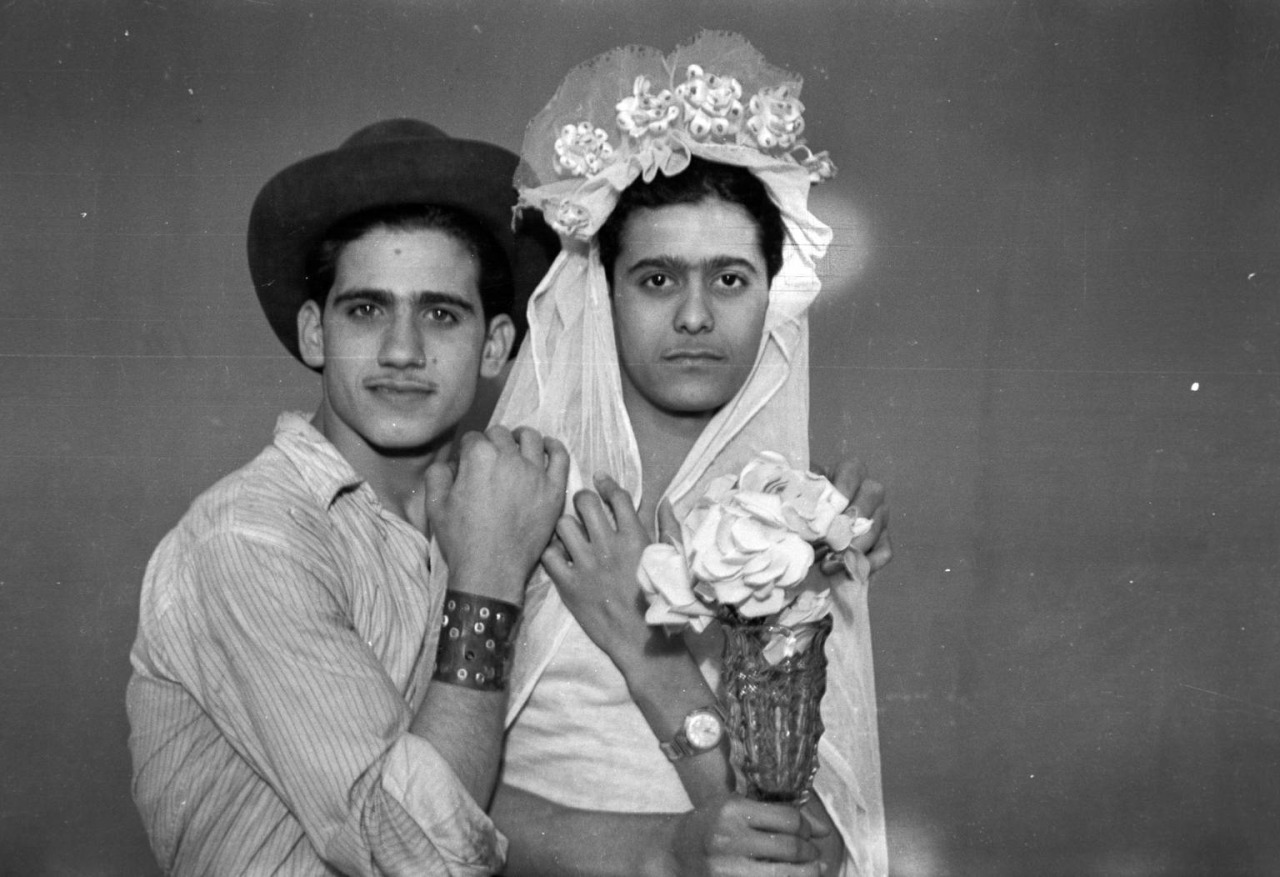

An anonymous pair photographed in Hashem El Madani’s Studio Shehrazade in Lebanon in the 1970s (courtesy the Arab Image Foundation)

The same interest in archival images can also be found in Middle Eastern photography6. Artist Akram Zaatari co-founded the Arab Image Foundation to collect, preserve, and study photographs from the Middle East, North Africa, and the Arab diaspora, and the Foundation now houses over 600,000 images. In 1999, Zaatari discovered the extensive archive of Lebanese photographer Hashem El Madani’s Studio Shehrazade in Saida, Lebanon, and has been working to document and disseminate it ever since. Zaatari describes El Madani’s studio work as ‘both descriptive and inscriptive of social identities’7, commenting on not only the visible manifestations of external realities within his images, but also on how the ability to present one’s reality in the form of photography changed the way individuals saw and projected themselves.

Studio photography predominantly emerged as an expression of the individual; and yet, today, there is an overwhelming move to extrapolate the individual to the masses as representing a time, place, or people

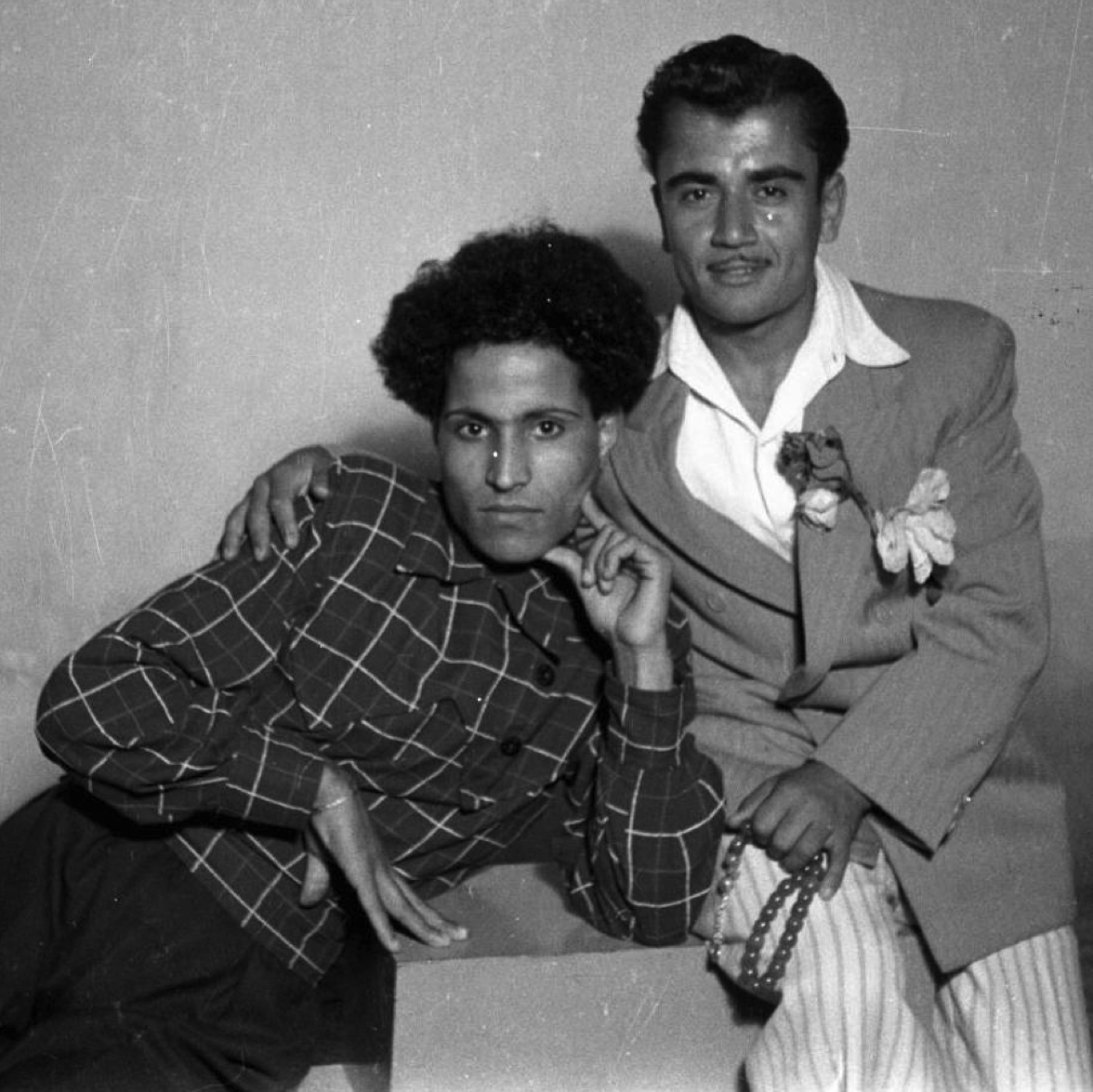

Najm (left) and Asmar photographed in El Madani’s studio sometime in the 1950s (courtesy the Arab Image Foundation)

There is truth to this: undoubtedly, the contexts of a person’s environment do affect the way they see and represent themself; but, equally, the photographic studio must be seen as a transient space. El Madani’s studio ‘created a site where individuals could act out identities using the conventions of portrait photography, with poses inspired by the desires of the sitters’8. In this respect, the studio also becomes a place where one can escape ‘realities’ and take on identities that may not have anything to do with the social and political atmospheres of their time. In a book on El Madani’s archive, art critic and theorist Stephen Wright argues that it is possible to learn about society through the details of studio photographs. ‘If one examines these “little pictures” carefully enough,’ he says, ‘the elusive bigger picture comes into focus through the hopes and aspirations of an entire population’9. This sort of ‘forensic’ analysis and extrapolation of historical photographs denies the studio of its emancipatory and creative elements; such endeavours can be seen as a return to 19th century presumptions of photographic ‘truth’. Rather than justifying the ‘reality’ of the image, perhaps there is much more to be learned from the performativity of the individual within such images, in one of the few spaces were people can express their innermost thoughts and feelings: the photography studio.

Joe (courtesy Omarivs Joesph Filivs Dinae and Tarek Moukaddem)

A new collaborative body of work by Lebanese photographer Tarek Moukaddem and Palestinian textile designer Omarivs Ioseph Filivs Dinae looks more closely at the transient element of studio photography. Described by the artists as an experiment in dress and photography, Stvdio El Sham [MMXIII – MMIII] looks at performativity and identity within an attempted reconstruction of an early 20th century Levantine photography studio. For the artists, the photography studio is a place ‘where the imagination can make or unmake realities’10. The six photographs, each capturing a single, full-body image of a male subject in various outfits and with different props, do not evoke a single ‘bigger picture’ or offer a narrative (or counter-narrative) of what it is to be Arab or male today. What can be read from the images is an expression of individuality, of a presentation of alter-egos or imagined characters that appear as both ridiculous and hyper-styled. The artists describe them as resembling ‘a band of makeshift superheroes’, and their work rejects the kind of attributive analysis that Wright speaks of in his conclusions on El Madani’s archive. One should not look at the Stvdio El Sham images and generalise their representations into an overview of ‘Sham’ society, and to avoid such attempts, the photographs purposefully give no contextual details to explain the choices made in dress, poses, and props. The images capture a fleeting and unique moment of performance in a world where such acts are often restricted.

Abu Saleh (courtesy Omarivs Joesph Filivs Dinae and Tarek Moukaddem)

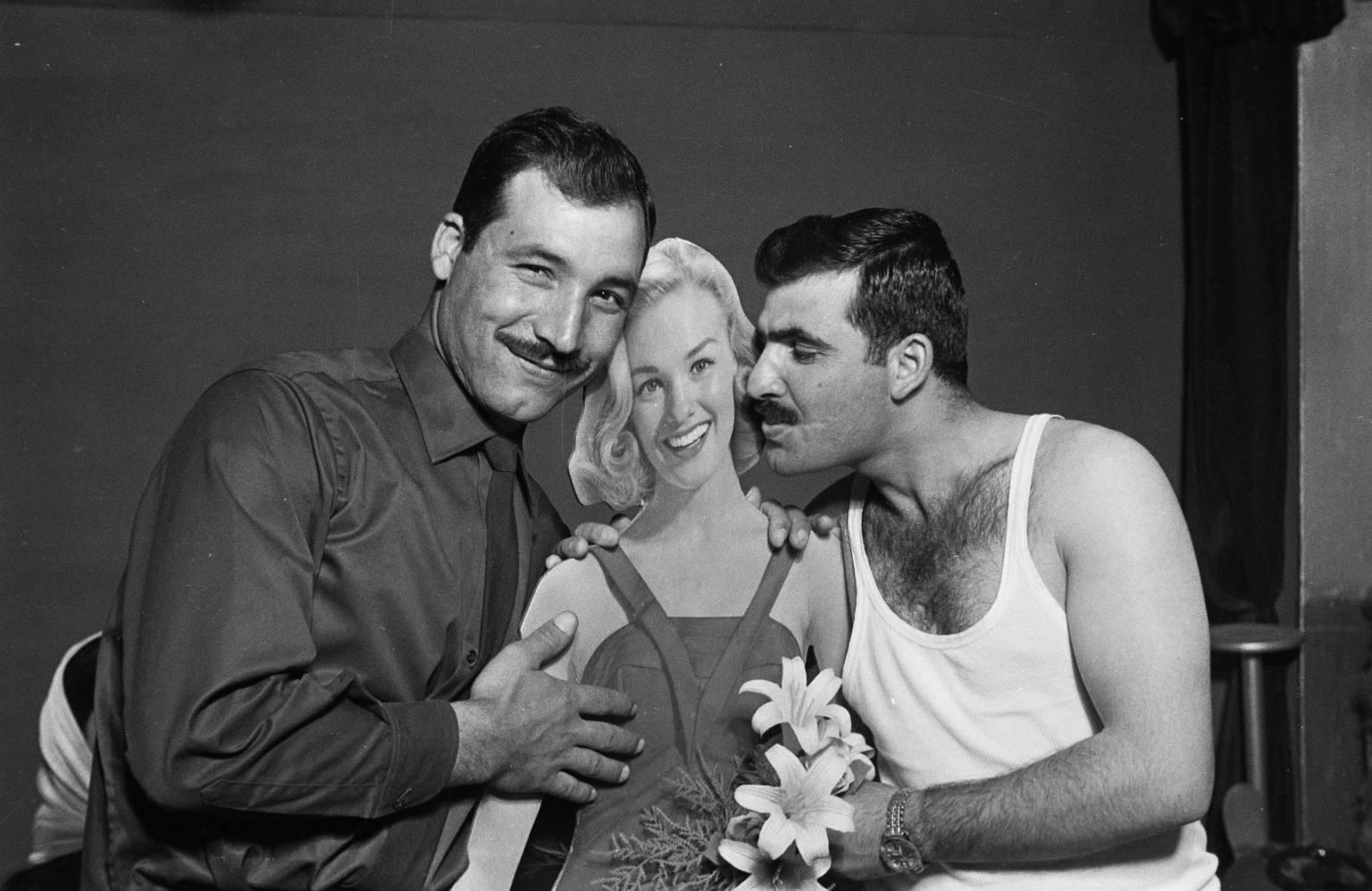

The same can be said about some of the images in El Madani’s archive. The Studio Shehrazade archive is vast, and mostly includes photographs made for identification purposes; some, however, are much more spontaneous and playful. Much like with Stvdio El Sham, El Madani’s subjects use dress and props in their images to imagine alternate identities and personalities. Whilst it is possible to look at these items of clothing and objects as signifiers of a certain time and place – where flared jeans and transistor radios abounded – this view somewhat discredits the agency and creativity of the sitters, generalising their images into a collective history and narrative and ascribing messages, meanings, or themes to be used as visual historical ‘evidence’.

The process of studio photography leaves no doubts surrounding the question of ‘truth’ and interpretive representation within photographs. The relationship between sitter and photographer, and the choice of poses, dress, and props are all layers of interpretation that, if not fully remove it, distort the ability to extract ‘truth’ and ‘fact’ from a photograph. Studio photography predominantly emerged as an expression of the individual; and yet, today, there is an overwhelming move to extrapolate the individual to the masses as representing a time, place, or people. This move runs dangerously close, one might argue, to the Orientalist scenes and types images previously discussed. In attempts to understand historical moments through visual materials, and, conversely, to contextualise visual materials with historical details, one must not lose the creative and independent individual within. In simply presenting an imagined reality and overtly-performative identities, Stvdio El Sham reminds viewers that they must avoid notions of homogeneity and stereotypes, and that photography can be an aesthetic, fun, and spontaneous moment in and of itself.

Phillip (courtesy Omarivs Joesph Filivs Dinae and Tarek Moukaddem)

‘Stvdio El Sham [MMXIII – MMIII]’ runs through November 8, 2015 at the Muse Gallery in London as part of the Nour Festival of Arts.

Click here to download this article’s bibliography.

Cover image: Ahmad el Abed and his friend Rajab Arna’out photographed by Hashem El Madani sometime between 1948 and 1953 (detail; courtesy the Arab Image Foundation).