The best of times, the worst of times: remembering Lebanon through photographs

I’ve been living so long with my pictures of you, that I almost believe that the pictures are all I can feel …

- The Cure, Pictures of You (1989)

They came from different worlds, Ania and Diab, who met each other one day in the squalid splendour of Camden Town, with its smell of rancid noodles and grass and the sound of whistling plastic birds by the canal. Diab was down and out, having split from his wife, and Ania had just begun an artist residency at the hostel where Diab was staying in the interim, as he wondered where life would take him next. With his broken English, and Ania’s ‘non-existent’ Arabic, communicating through tongues was trying; but it didn’t matter. Where words failed them, pictures filled the voids – lots of pictures; for Diab not only took pictures, but lived and breathed them. Alone in manic London, trying to find his way, it seemed the pictures of his cherished homeland were all he had. He hadn’t left those gilded days of late in Beirut and elsewhere, beneath rubble and ash and between the crags of memory; you could see them in his eyes and the lines on his brow, feel them in the breaths that looked, in a way, like the fog of the Corniche when they condensed in the cold autumn air. And of course, one could see them, if they wanted, in the boxes and bags brimming with those photographs, faded, scratched, and weathered, each telling tales of the thitherto untold and unseen; tales that, with the vision of the young lady from faraway communist Poland, would be told once again. Someone once said that pictures make ghosts of people; better to let the spirits fly again, then.

I recently spoke with Ania about the genesis of A Lebanese Archive, her new book of photographs from Diab’s collection: a thick, warming volume of people, war, dreams, and those golden years when nothing could touch one.

How did you and Diab meet? How did he end up in the London hostel, and what was he doing with all those photographs? How did he show them to you to begin with? One would think that a person in his shoes would have with him only the bare necessities – not a treasure trove of photographs!

It made me feel connected to him instantly, because anyone for whom photography is a bare necessity has my interest! Even though I met Diab in a hostel for the homeless, he had never lived on the streets. As far as I know, he ended up living there after he’d divorced his wife and needed his own place, so in the [interim], he ended up living in the hostel. Because he’s disabled, he was eventually given an independent, sheltered accommodation; this is the story he told me. [Regarding the] photographs, he told me that he treasured them, that they were a sort of ‘rock’ to base his life, existence, and identity on, but that he had never really shown them to anyone except for his family all these years in the UK. He took great pleasure in knowing they were safe with him, but he didn’t know what to do with them. He has ambitions to be a historical writer. He writes in Arabic; his English is quite limited, and I think that added another ‘layer’ to the project. His English is broken, and my Arabic is non-existent, and so we communicated through these photographs with a lot of guessing, making many efforts to understand each other.

Zena Maghrebe of the Caracalla Dance Company at the Baalbek Temple in the 70s (photographer unknown)

As an artist-in-residence at the hostel, my job was to engage with the residents through the Creative SPACE programme I was running, so I invited everyone to meet me. Diab was one of the first, and was really keen to engage with someone, to start doing something. I asked him if he had any experience in photography, and he mentioned he had all these old photographs from Lebanon.

I’m fascinated by personal collections of photographs and many of my works deal with memory. I was really intrigued to see what he had. The next time we met, he came with two huge bags full of photos. That was my first ‘encounter’ with the actual archive, and I immediately thought that it would be great to do a project with his collection. He was so happy to meet someone who was as bonkers as he was about these old photographs.

What is Diab doing nowadays?

He says he’s written five books and it is his aim to publish them. They haven’t been translated into English, and I have not seen full drafts. From what I’ve understood, they’re about the history of Lebanon, tradition, and grand historical narratives. One of them is about places in Lebanon that are mentioned in the Bible, and another is about a typical day in a life of a woman from Baalbek – that sort of thing. He showed me a few pages that were translated using computer software, so they were impossible to decipher. I didn’t feel I could engage with his writing, nor can I comment on its merit … but his collection of photographs was a different story.

The Caracalla family wedding with Ahmad Caracalla, Abd Al-Karim Salah, Abu Saeed Solh, Abu Fakhr Shalha, Mustafa Caracalla, Ahmad’s uncle, Mohammad Caracalla, Walid Solh, and Ali Holhal, now a singer in Lebanon (photograph by Diab Alkarssifi)

The photo series are interspersed with snippets of conversations between you and Diab. In some of them, such as May Day, May Day, you recount your memories of Poland, while he ruminates on Lebanon; did you notice any similarities between your experiences in Poland and Diab’s in Lebanon?

Yes. Very often I would find myself looking at the images of the Middle East, which to me was a strange territory that existed only intellectually, as at that stage I’d never been there. Despite that and all the obvious cultural differences, I had a strong sense of looking at something that was instantly familiar to me. In Diab’s images there are all these photos of private lives from the 70s and early 80s, of people doing what we do as families and with friends: having parties, picnicking, laughing together, being silly at times. There were also other images of people in gatherings and demonstrations; all these were familiar to me, because of my memories of similar kinds of scenes during my childhood in the 70s, and under martial law in Poland in the early 80s. Even the clothes were similar to the ones in my family albums. In Diab’s photographs, it seemed that the tougher life got (e.g. with the Civil War), the more it made sense to capture it through photography, as if it were ordinary, as if everything was fine and beautiful. I didn’t have the same kind of relationship with photography in the 70s and 80s, but I had similar memories of how people were. I could also relate to the communist ‘dimension’ of many of the photos, as I grew up in communist Poland. Diab was involved in communist circles and there was a sort of communist pathos in many of his photographs, which was really familiar.

Om Ashad Qara, Ashad Qara, and village children (photograph by Diab Alkarssifi)

The photographs jump back and forth in time, as opposed to progressing chronologically, as one might expect. Why is this? How did you decide to categorise the photos?

I had been working with this material and slowly getting to know it for a couple of years during my artist residency at the Arlington hostel, but I realised quite early on that I really wanted to publish a book. There was material in there for several different approaches and concepts; the question was, what would be the first book that I would publish with this material? I decided to emulate a sense of discovery of this collection, as it was when I first encountered it. Then, I decided to create chapters and parts that would evoke the different forms of ‘interrogations’, or readings of the archive that I was performing. In places, there is an illusion of some kind of chronology within the book, where I pulled out some stories from the archive and presented particular strips of memories. The non-chronological ‘disruptions’ stem from my interest in connecting this material to a wider notion of archives and the role they can play in a social context. Archives are never neutral; they are often presented to us, or linked to the Powers that Be as narratives that are supposed to offer us a sense of identity. But they’re very fragile, very unstable, and can be easily manipulated. Here, I was manipulating [the archive] as an artist.

Although they are built from fragments of history, archives are not about preserving the past as much as they are about informing (or misinforming) the present and the future. This shift in thinking about archives is important to me in general, and it informed my approach to this book.

Monir Al-Ahmar in Al-Labweh in the 70s (photograph by Diab Alkarssifi)

The descriptions of the photographs are all in the appendix, rather than in any captions; why so? Would you say the book is more an experience than a historical document or specimen?

Yes, I think so … or at least I was hoping it would be. I strongly believe that as human beings, we use narratives and create narratives in order to make sense of the world and ourselves. I wanted to extract the photographs from the context in which they were taken for just as long enough as to provoke a guessing of what kind of narratives they might contain. The captions and dates are at the back, but I wanted the first reading of the photographs not to be framed by them, but rather by one’s own intuition. On one hand, I wanted to create a space for fantasy and the freedom of multiple readings and interpretations, and on the other, I hoped to reveal how often we make wrong judgments about perceived situations. This is particularly relevant to the Drift/Resolution section of the book, containing the irregular grids of photographs. I‘ve pulled images out of a chronological context there to evoke different kinds of stories than those already out there, that have been told to us (or sold to us) as narratives we’re supposed to take at face value.

An unknown woman in the 50s (photographer unknown; from the Baalbek Family Archives and the collection of Diab Alkarssifi; courtesy Hikmat Awada and the Baalbek Photo Print Studio)

More than anything, A Lebanese Archive is a book about people. There are, however, certain pages devoted to bleak-looking landscapes; what are these intended to signify?

For me, landscapes are always embedded within complex patchworks of memory, both personal, cultural, and collective. They’re never innocent or just aesthetic or romantic to me; they’re question marks. They’re constructs. To me, landscapes are never just about physical space or territory, but also timelines. In a way, the more beautiful and arresting they are, the more I contemplate why and how they have the power to make me believe that they offer some kind of escape. What kind of narratives and questions do they possess beyond geology or nature, or the picturesque? With the landscapes I’ve weaved into this book, there is this idea of offering some breathing spaces to the reader: breathing spaces loaded with secrets.

[Diab] calls them the ‘good old days’, even though he’s talking about years of war, and intense, brutal conflict that he witnessed first-hand … but his days in Lebanon were some of the most beautiful of his life

For example, the photographs of the mountains covered in snow are almost abstract because of the geometric patterns formed by the patches of white snow and the high contrast between them and the monochromatic terrain; there is this kind of formal photographic aesthetic that is very beautiful in them … but at the same time, I know that these photos come from rolls of film containing images of militia camps during the Civil War. These landscapes are therefore loaded with all sorts of hopes and dangers of the war that all the men and women partaking in it might have felt … All these fundamental primal fears and hopes, I imagine, load these photographs with metaphorical overtones. What would it take for these sorts of landscapes to simply become breathing spaces again, landscapes liberated from the historical events that ‘define’ them right now? Could they ever be just landscapes?

The Ouyoun Al Siman mountains, as seen from the Lebanese Communist Party militia camp (taken sometime between 1976 and 1979 by Diab Alkarssifi)

Are there any particular images that you found yourself attracted to? There’s this one of two girls kissing amidst ruins that stopped me in my tracks. I can’t stop looking at it.

I’m really so happy to hear that that stood out for you, because it’s one of those ‘quiet’ images, as I call them. I’ve written about them in the book as being ‘peripheral images’, images you can tell were quite badly shot, or that appear as ‘mistakes’; they’re certainly not perfect, but they’re beautiful in my opinion. I guess, in one way or another, every single image that I’ve put in the book stood out for me at some stage, but it’s like choosing favourite songs or books: my favourites change over time.

There are some, nevertheless, that definitely hold their position in the top ten. It’s so interesting having this conversation with you, because when the book came back from the printers, I almost couldn’t see it anymore! Now, I’m finally able to look at it and read the book again. It’s interesting that my favourites are still pulling on the same heartstrings. There’s one ‘bad’ black-and-white image with scratches on the negative and birds flying behind them. There’s also a 70s photo of a guy who’s smiling as if he’s in another universe. He’s lying on the ground and looking up into the sky and just smiling with this heavenly look. And the one of the kissing girls: it’s almost as if the image is dissolving in front of your eyes – there’s something unstable about it, and something very tender inside it. It’s almost like a bruise; it hurts a little bit. It’s that kind of image. It’s physically tender. And there’s a picture of this unmade bed that appears as if there’s a body inside it, like someone’s taking a nap in the daytime. It has these faded yellows, and feels as if someone’s been sleeping very late into the day, but you can’t see a face; it’s like the person has been lost within the bed for a very long time …

A photograph taken by Diab Alkarssifi during a family visit in Baalbek in the 80s

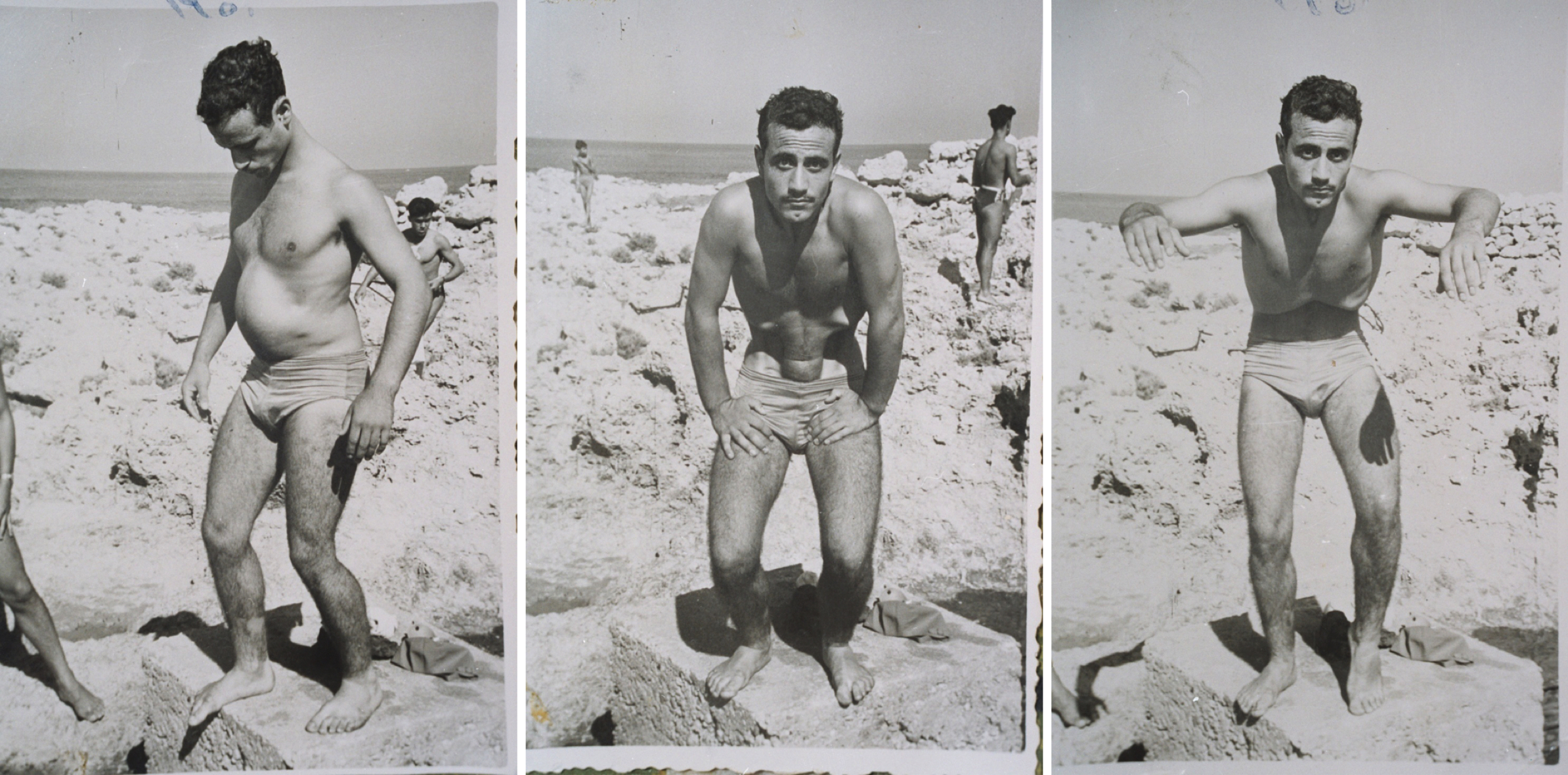

What are the ‘dreamers’ in the last section dreaming about? Who are they, and what are they doing by the sea?

I took all the contemporary photographs in October 2013, when I first went to Lebanon, as well as in April and May last year, when I was in Beirut for a residency at Ashkal Alwan. I used to refer to Diab and myself as ‘archive dreamers’, two people dreaming two different dreams about this archive coming back to life, each with our own aspirations for the project.

As I started meeting people in Lebanon and telling them about the project, I saw we were all dreaming about some kind of possible future that an archive might allow us to access. I started thinking about the archive as being a site of aspiration, rather than a doorway to the past again. Everything became metaphorically linked to some kind of conjectures about what people might want from a society, from a culture, or as individuals; I wanted to tap into this idea of a dream. When you read the contemporary images in sequence, the present flanks the archival past and pierces it through the centre of the book. Water reappears in cycles as the sea viewed from the Corniche and the mountain fog in the Bekaa Valley, obstructing all visibility into the past, be it a happy or traumatic one. The water came to symbolise for me some kind of theatrical ‘curtain’ opening up and closing down, allowing some dreams to come through, both good ones and nightmares; I don’t know … The sea became a metaphorically-loaded site for me, and, I am guessing that it was for the dreamers captured in my photographs as well.

Yasin’s New Year’s Eve party in Baalbek, 1977/78 (photograph by Diab Alkarssifi)

The Lebanese (although one can never generalise) are often mentioned as a people desiring to forget about their recent history, particularly that pertaining to the Civil War era. Why do you think Diab has chosen to keep all these assorted images?

Diab was forced to leave Lebanon and emigrate to the UK. He loves Lebanon and idealises it. For him, the past contained in his archive is a capsule of a home he cherished – perhaps not just a memory, but possibly a seed, from which he could grow some form of reality reflecting what was captured in the pictures. It’s an impossible dream because the past is the past, and everyone including Diab, knows that it was far from perfect. He calls them the ‘good old days’, even though he’s talking about years of war, and intense, brutal conflict that he witnessed first-hand. He told me that he was a humanist and hated war, but that his days in Lebanon were some of the most beautiful of his life. In the UK Diab lost his sense of purpose, and it’s beautiful to see that the project has helped him find it again. He’s full of ideas and ambitions for the future.

We all choose and pick different things that reinforce a sense of who we are and remind us of what’s important in our lives. I can’t really speak on behalf of ‘the Lebanese’, or Diab in relation to that self-imposed social mass amnesia you are talking about. But I talked to a lot of people in Beirut about our relationship with the past who were aware of the importance of history, and who felt that this amnesia was dangerous –

Beirut, 1960s (photographer unknown; from the Baalbek Family Archives and the Baalbek Photo Print Studio; courtesy Hikmat Awada; from the collection of Diab Alkarssifi)

– So they didn’t want to forget, then …

Most of the truly inspiring people I met in Lebanon were fiercely dedicated to focusing on what they were doing in the now. Still, they were all incredibly supportive towards my project, generous, considerate, and willing to discuss all sorts of ideas, always encouraging me to persevere. People would often tell me how important, in their opinion, projects like mine that engage with cultural and historical heritage were. I got the impression that the majority of them thought this attitude of ‘let’s forget and move on’ was like walking on thin ice.

I would not be surprised to hear that there are a lot of people out there who want to cultivate this amnesia as a way of dealing with collective trauma. There are a lot of metaphorical skeletons connected to the pain that was inflicted and suffered. Many archives have been destroyed, hidden, or lost in Lebanon due to a carelessness concerning recent cultural heritage and the fear of the surfacing of potentially contentious content or ‘problematic evidence’.

Imad Alahmar, Mohammad Caracalla, and Hussein Al-Naboush on Nahle Road in Baalbek in the 70s (photograph taken either by Diab Alkarssifi or Mohammad Caracalla)

Contrary to that, I would say that the artistic, academic, scientific, creative, cultural, and entrepreneurial circles want to engage with archives like Diab’s actively and critically in a way that goes beyond finger-pointing, towards something positive. That’s why this project has resonated with so many people. There’s this sense of genuine excitement about the positive impact that reconnecting with the cultural heritage contained in an archive like this might have.

‘A Lebanese Archive’ by Ania Dabrowska, co-published by Book Works and the Arab Image Foundation, can be purchased via Book Works and at the Arab Image Foundation in Beirut.

Cover image: Diab Alkarssifi - Ietedal Alkarssifi and a friend kissing at the Baalbek Temple in the 80s (detail; courtesy the collection of Diab Alkarssifi).

The introduction to this interview will appear in the forthcoming issue of Tribe Photo Magazine.