Or, Ali and the little boat that will take him to uncle Sadik

Encounters with place, memory, and identity arise as questions in Ali’s Boat, a highly personal multimedia installation by Iraqi-born artist Sadik Kwaish Alfraji. Curated by Nat Muller and accompanied by a book launch surveying Sadik’s major output, the exhibition’s success in Dubai has been in no way subdued by its migration to London, where it was shown during the recent Shubbak Festival, and where it will remain on display until the end of August. A story deconstructed and rebuilt, which simmered in Sadik’s subconscious for a decade, Ali’s Boat follows the first meeting with his nephew in his native Baghdad. The notions of memory, home, and journeying – which might jostle for space in a more constrained work – find fulfillment in Sadik’s immersive video narrative, which I recently discussed with him in London.

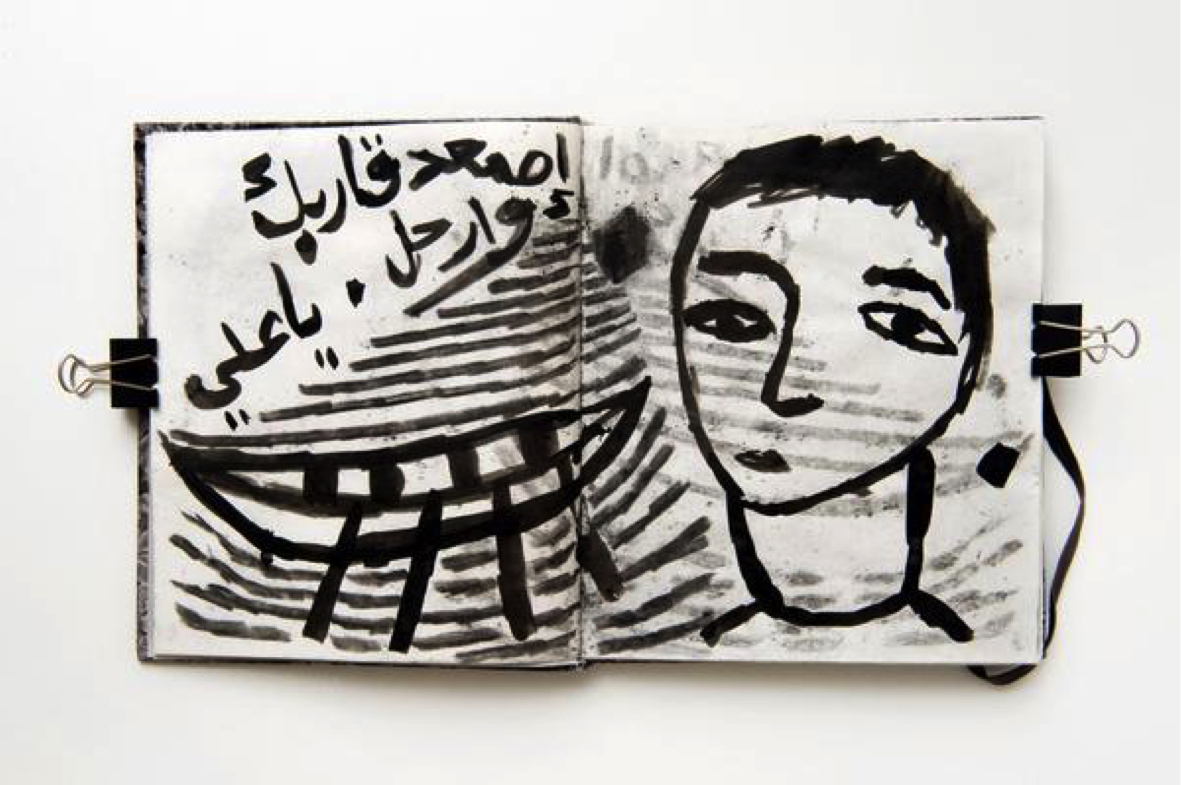

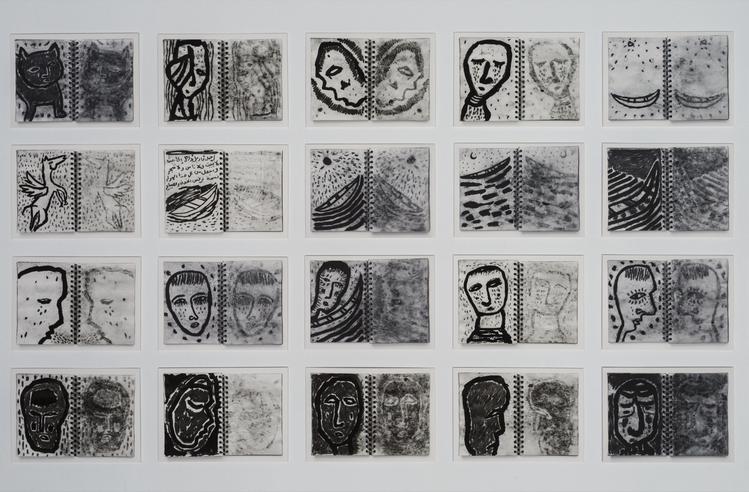

We met at the British Museum, currently featuring an exhibition of modern Arab art. For several years, Sadik laid down over 3,000 drawings in charcoal and Indian ink as foundations for his stop-motion video piece, and one of these books features in the exhibition, alongside works from the late Rafa al-Nasiri and other artists from the region. Opened to a portrait of the eponymous Ali rendered in thick lines, the book feels somewhat marooned from its context in the engulfing video experience that constitutes the main part of the exhibition at Ayyam Gallery, where its pages act as physical companions to the digital experience.

An excerpt from Ali’s Diary (courtesy Ayyam Gallery)

Sadik and I sat in the Great Court of the British Museum, where we talked for several hours as the noise and crowds swelled around us. Sadik’s conversational style is much like his art: expansive and emotional. His work comes down to what he terms ‘margins’; Sadik likes to gaze at in-between spaces, engrossed in the existential relationship that endures between his own identity and the physical spaces he inhabits. His work wrestles with the tangible and the ethereal, and Ali’s Boat finds an unusual unity of physical and digital mark-making. The process of continuous gesture and erasure in the video reflect ideas of gain and loss, and the sometimes playful (and often cruel) transience of memory. I wonder if Sadik sees an inherent sadness or melancholia in memory; audiences are often visibly emotional after viewing the piece, but he corrects me. A difference certainly exists between the nostalgia we all experience and the discovery that the very physical spaces that have encased our domestic memories have literally crumbled and altered so drastically as a result of conventional war. Sadik uses the myth of Sisyphus to homogenise Middle Eastern politics post-Arab Spring: a persistent, punitive cycle without a discernable conclusion.

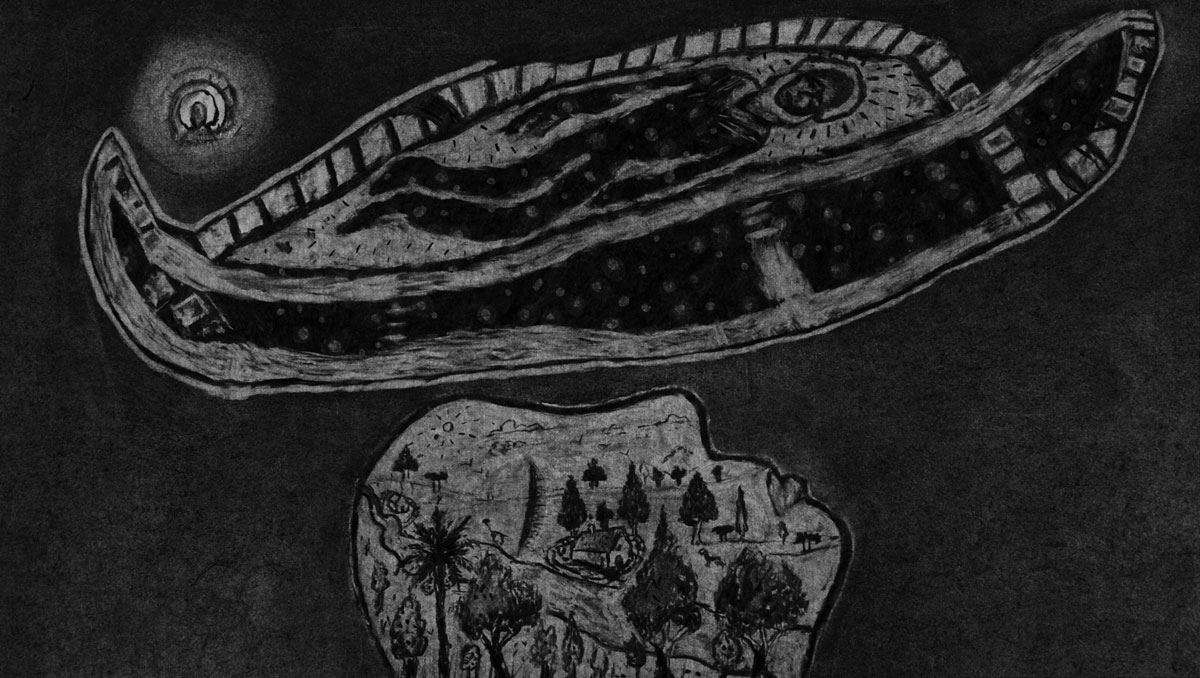

Still from Ali’s Boat (courtesy Ayyam Gallery)

A preoccupation with the Self lingers throughout Sadik’s body of work, and the shadowy self-portrait that looms within his video pieces is by now a familiar metaphor when coming to consider Ali’s Boat. The artist’s body is treated as a physical landscape, within and upon which his memories are enacted. Rooms, buildings, and cities grow and shrink, and tears fall to become rivers. Both visually and conceptually, Ali’s Boat pits the microscopic against the colossal, the scope of a young boy’s fantasy against the scale of a real war that relentlessly denies and resists. The restless metamorphosis of the sequence recalls my favourite of Sadik’s pieces, Godot to Come Yesterday, in which two spectral figures drift around one another in a brooding choreography of dance and dialogue that never quite achieves symmetry.

Sadik seems to enjoy his residency within this uncertain peripheral space, finding more solace in the process of asking than answering questions through his work

Pages from Ali’s Diary (courtesy Ayyam Gallery)

The narrative in Godot to Come Yesterday resembles a conversation between a past and future version of the Self, which Ali’s Boat continues and complicates, integrating ideas of nationality, politics, and the family in a consideration of his own identity. When Sadik left Baghdad to study and work in the Netherlands, a bewildering sense of mutual abandonment seemed to settle in his mind. His reflections on ‘home’ continue to flicker between the literal and the existential, and pose an important challenge to a global population more scattered than ever before. Returning to his earlier emphasis on margins, Sadik seems to enjoy his residency within this uncertain peripheral space, finding more solace in the process of asking than answering questions through his work. Sadik is often regarded as an artist in exile, and his relationship to his own diaspora is tussled with, particularly in the work he produced after visiting Baghdad. During our conversation, he strongly rejected the notion of nationality in art, seeking refuge instead in the anonymity he feels in the process of creative expression. While so much of Ali’s Boat is very significantly tied to thoughts of Iraq, Sadik seems uncomfortable with an ‘Iraqi’ definition being imposed too strongly on his identity or output, perhaps ill at ease with the implicit politicisation it carries.

Music plays an integral role in the majority of Sadik’s work. The visuals of Ali’s Boat are eloquently heightened by the accompaniment of a melancholy assembly of strings, and the intensely internalised product of this combination raises questions about how Sadik regards viewers’ roles in the experience. We talked about audiences in Dubai compared to London, and the similar emotional charges that lingered following each screening as the video loops in six-minute cycles. For Sadik, this effect serves to strengthen his conviction in the humanising potential of his art, the ability to connect whilst disregarding concerns of origins.

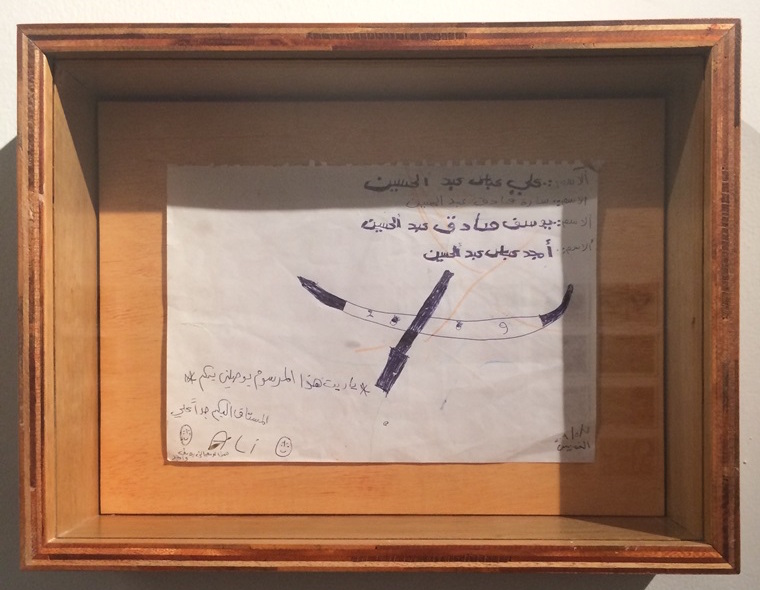

The crux of Ali’s Boat, one could say, is Sadik’s sense of dislocation; and, along with another of his major works, The House that My Father Built, Ali’s Boat comes about as an artistic product of his first – and only – visit to Baghdad since his relocation to Europe. Some time following the death of his father, which he candidly discussed with remarkable sincerity, Sadik was compelled to visit his mother and extended family to share in their grief. Overwhelmed by his own emotional reaction to the devastation he witnessed following the American invasion, and the gulf between the imagined city he grew up in and the reality that confronted him, Sadik cut his trip short. His experience of dealing with a complicated and consuming guilt are palpable in his work, and elucidated by his words. While Ali’s Boat ostensibly stems from a letter to his nephew, who imagined a boat that could carry him from Baghdad to Amsterdam and the safety represented by his uncle, the effect was wholly transporting for the artist: the boat Ali drew instead conveyed Sadik back to Baghdad and the relationships he left there.

Ali’s Letter (courtesy Mashaael Basheer and Al Mahha Art)

As our conversation came to a close, Sadik and I spent time choosing presents for his partner and children in the museum’s gift shop. We took one last look around the Ancient Iraq gallery, where we stared at early tools and carvings, objects whose safety is ensured by a separation from their context, far away from home. I walked him out, giving him directions to the National Gallery, where he would spend the afternoon before boarding a plane back to his family in the Netherlands – another place he was careful not to refer to as ‘home’.

‘Ali’s Boat’ runs through August 29, 2015 at Ayyam Gallery in London.

Cover image: Snakes and Ladders (courtesy the artist).