An epic journey from Ottoman to modern Iraq through the eyes of a family

O, Babylon: pray, relate the tale of thy haughty sons and daughters, who with brazen cupidity strove to thrust their wanting hands into the clouds of the climes on high, vying with Marduk for his lofty station. Where be Nebuchadnezzar and the great Belshazzar, who learned too late of the writing on the wall and his wide dominion soon to fall? Thy hanging gardens lie now fallen and ravaged, thy hallowed name hath been sullied by a seven-headed whore, and thy rivers run red and black with the blood of men and the pages of your past; Shamash hides behind blackened, billowing clouds of smoke, and the once mighty gates of Ishtar stand subdued and open to all and sundry, as but a memory of what once was and what shall never again be. Babylon, begotten beneath an ill-omened star, thou and thine unlucky earth wert destined to bear witness to the anguish of men, sovereigns, and gods alike; where salvation? Where respite?

* * *

Samir is a hip, young twenty-something with bushy eyebrows and thick-rimmed spectacles who spends his time dabbling in leftist politics, working with typography and film, and soaking in the sonic madness of the political American garage rock group The MC5. Though his mother is Swiss, Samir has never truly felt he belongs in a land of snow-capped mountains, cheese, and escalating fascism, and, come to think of it, he and his family have never had any Swiss friends despite having lived there for so long; their friends have always been from somewhere else. Perhaps it’s the eyebrows that give him away so easily, and betray the suave European appearance he may have wished he possessed. Samir, like countless other Iraqis, is a déraciné, uprooted and displaced by an ominous chain of events in his native Baghdad which left little hope for his family, who decided to seek their futures and fortunes elsewhere.

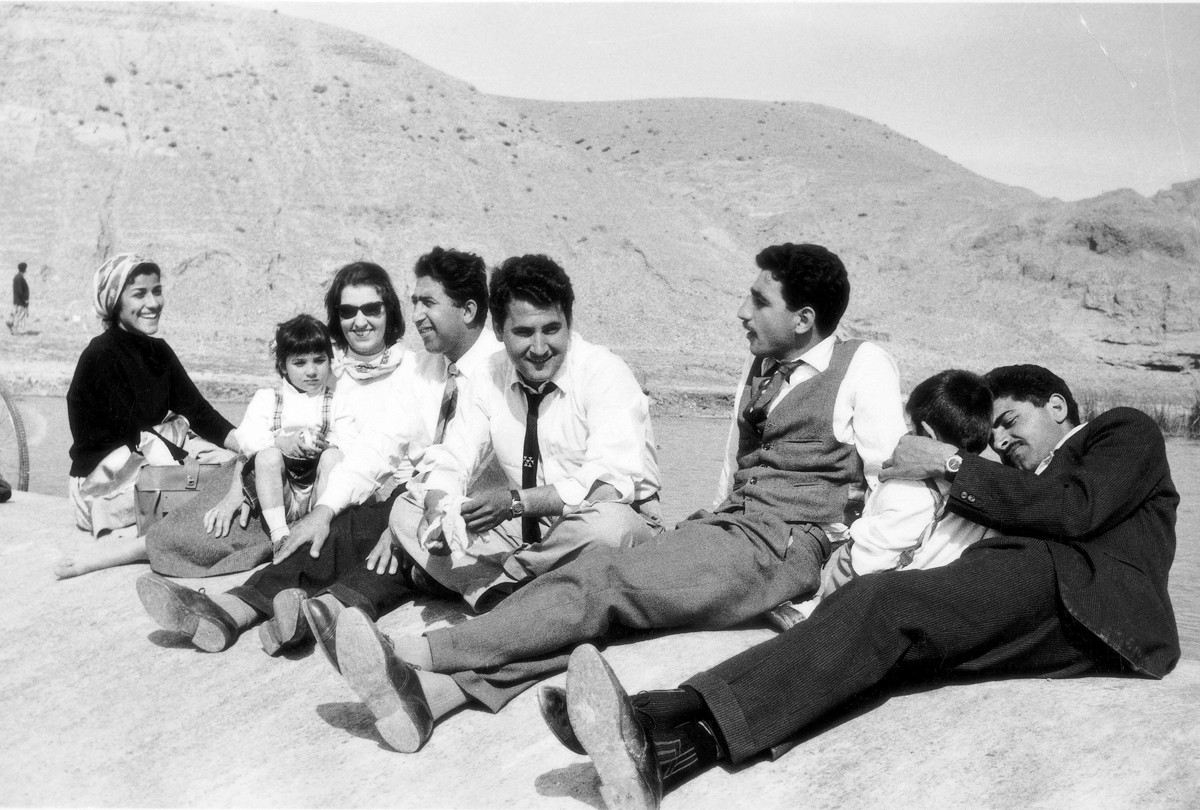

A family photo from the archives of Samir

‘I’ve always been obsessed with my family’s stories’, says Samir at the beginning of his ambitious film Iraqi Odyssey. Straddling a telling of his generously-sized family’s history and that of Iraq from Ottoman times to the present, his aptly named feature is nothing short of epic. Although the focus in the nearly three hour-long, stereoscopic film is on Samir and his relatives, it is not in any sense limited to them; according to some statistics, an estimated four to five million Iraqis live outside Iraq in an ever-growing diaspora. Through telling the stories of his uncles, aunts, and siblings, all of whom are scattered about in different parts of the globe, Samir not only provides insight into the condition of his relatives, but also that of the aforementioned émigrés, many of whom simply found themselves in the wrong place at the wrong time. But, then again, one could argue that ebullient politics, revolutions, sectarian strife, and war have always been integral to the Middle Eastern ‘experience’.

A chronological film, for the most part, Samir’s ‘odyssey’ begins in mid-19th and early 20th century Iraq, when the country was under the rule of the Ottoman Empire – the ‘Sick Man of Europe’ at the time – which had divided Iraq into the vilayets of Mosul, Baghdad, and Basra. Hurried black-and-white scenes of men in fezzes in bazaars, winding lanes, and petite rowboats on the Shatt al Arab (alternatively known in Iran as the Arvand Rud) depict a time when, as Samir fondly mentions, people of different ethnicities, religions, and language groups comingled in seeming harmony, and a certain respect was afforded the black turban of the seyyed. Here, the director also evinces his family’s origins as seyyed Shi’as from southern Iran, an area which many years later would serve as the frontline between a belligerent Ba’athist Iraq and a nascent Iranian Islamic Republic.

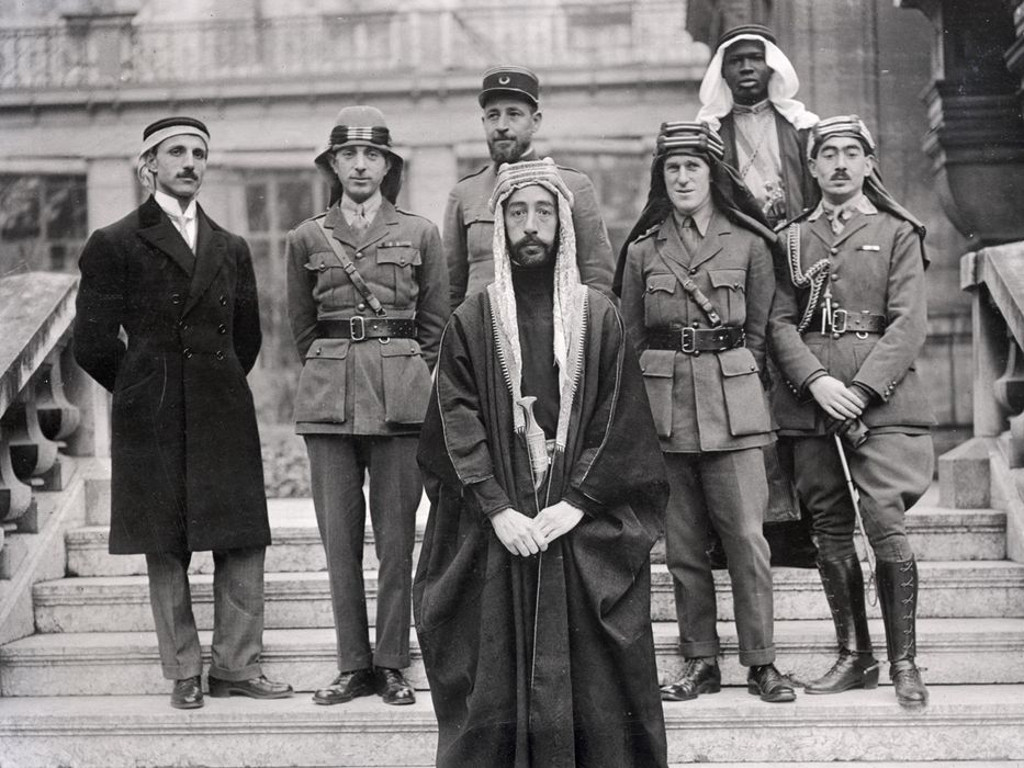

Faisal I of Iraq (centre) with T.E. Lawrence (third from right) at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919

As the story of Iraq slowly unfolds, and Samir takes the audience on a journey from the Ottoman era to the installation of the British-backed King Faisal (a close friend and ally of T.E. Lawrence, a.k.a. ‘Lawrence of Arabia’), Abdelkarim Qasim’s coup d’état in the 50s, and the rise of the communist – and later, Ba’athist – parties, so do the stories of his innumerable relatives, whom he personally sees, tracing his journeys along the ways. One uncle, an ophthalmologist, he visits in a typically tiny London home near Heathrow airport; his half sister, Souhir (30 years his junior), in a bleak, almost derelict suburb in Buffalo, New York; an aunt coming to terms with lackluster life in Auckland, and a leftist uncle in Moscow, who is as happy walking along the city’s frostbitten avenues as he is sipping on vodka with his hiking buddies. Although life has gone on for all of them, there still, nonetheless, seems to be a gaping void in their lives, ever lurking in the shadows. Watching them narrate their stories as the history of their country is played back in a series of archival reels behind them, one can’t help but think what their lives would have been like had they stayed in Iraq, if they will ever return, and perhaps, above all, where everything went awry. Indeed, as Samir alludes to towards the end of the film, when will we return? is a question on the minds of not a few Iraqis who still harbour hope within their hearts.

Straddling a telling of his generously-sized family’s history and that of Iraq from Ottoman times to the present, Samir’s aptly named film is nothing short of epic

The Baghdad of the 50s and 60s in Samir’s film is one that may come as less alien to those unfamiliar with Iraq than the dismal picture so often associated with it today – and understandably so. Here, double decker buses and Volkswagens swerve about roundabouts worked by nervy, whistling policemen in gloves of purest white, while the eyes of dapper, chic bachelors meet the languorous kohl-rimmed gazes of coquettish damsels on swanky Rashid Street. At home, far from the madding crowds in Tahrir Square and the dusty bazaars, families sit affixed to their television screens, enthralled by an impassioned, imploring Om Kolthoum waving about her proverbial handkerchief in rapture, while in the place of Western film idols, pictures of Mohamed Abdel Wahab line the walls of love-struck teenagers. It all seems to good to be true, and, with hindsight, one cannot be blamed for believing so; for, following the rise of Saddam Hussein and the Ba’athists in the late 60s, Baghdad would enter only the beginning of a slow, painful end.

Baghdad’s Rashid Street in 1956

Samir and his relatives had left Iraq well before the rise of Saddam, mostly out of a desire to study abroad in Europe. While it cannot be said for sure whether or not they intended to return to Iraq, the escalating tension and overall state of fear and anxiety brought about by the Ba’athists obviated any rational possibilities for them. At a family gathering in Beirut in the 70s, Samir’s relatives contemplated a return to Iraq, although in the end, only two of them actually did go back. Watching the footage of 70s Iraq as Samir’s subjects candidly spoke about those tumultuous days, it is not difficult to understand why. Sepia photographs with ruddy overtones capture scenes of hanged Jews, believed to have been conspiring with Israel. Further on, in black-and-white film, a cocksure Saddam Hussein is shown addressing members of the Ba’ath party, coolly taking drags on a cigarette and wiping the sweat from his brow as he casually orders the execution of ‘traitors’. ‘And what do we do with traitors?’ he asks the half-terrified crowd; ‘We show them the sword’. The names of two incredulous, almost stupefied individuals are called out, of whom no trace will remain in but a short while. Perhaps out of fear, devotion to the party, or both, the sentences elicit ejaculations of frenzied fervour for Saddam and the Ba’athists by one or two individuals, which are soon echoed by the rows of their mustachioed, bespectacled comrades.

An Iranian soldier grieves beside the body of his fallen brother in Iran’s Kermanshah province during the early days of the Iran-Iraq War

Almost immediately following his ascendancy to the role of President in 1979 – coinciding with the fall of the Shah of Iran and the establishment of Ayatollah Khomeini’s Islamic Republic – Saddam Hussein, who for years had had his eyes set on the oil-rich Iranian south with its pockets of Arab minorities, calculated that the timing couldn’t have been more opportune for a full-scale Iranian invasion. Backed by Western powers, Iraq engaged in an eight year-long war with Iran, in which the former sought to revive the memory of Qadisiyya among the majus*. After the US had knowingly – and without any regret – shot down an Iranian passenger plane en route to Dubai in 1988, Khomeini decided to ‘drink the chalice of poison’ and call for a ceasefire, despite having against all odds gained the upper hand in the conflict. This was not to be the end of Saddam’s imperialist ambitions, however; only three years later, Iraq would invade nearby Kuwait, although this time, his former American allies sent his soldiers back with their tails between their legs. As one of Samir’s uncles remarks with a tinge of sadness, this defeat was truly the end of Iraq as they had all known it. After little over a decade of harsh US-imposed economic sanctions and international isolation – all while the Husseins and their henchmen were growing ever more prodigal and depraved – the great Ba’athist would be hanged, Baghdad sacked, the House of Saddam laid to waste, and Iraq once again under foreign occupation.

‘Penelope waited, despite the advances of her many suitors, but Iraq didn’t’, laments Samir’s uncle in the UK, drawing comparisons between Homer’s Odyssey and the present state of Iraq, as well as adding a new dimension to the fabled Whore of Babylon. ‘Iraq didn’t. The Iraqis sold themselves to the Americans. Iraq is Penelope’. In watching such haunting films as Iraqi Odyssey, especially given its focus on Samir’s family, one, to a degree, expects a sort of ‘happy’ ending. Granted he is able to reunite his scattered relatives together in Switzerland for the film’s epilogue, the film ends on anything but a positive note. After watching Samir’s film teary-eyed and in full for the first time, a debate ensues regarding the future of Iraq. Samir’s uncle in Moscow is adamant that the Iraqis themselves will rebuild the country and lift it out of its dire circumstances, and comments impassionedly on the chain linking dreams, thoughts, actions, and revolutions. Samir’s other uncle in the UK, however, is less of an optimist, and brings to mind the cruel reality that most of Iraq’s brightest minds have left the country. How can Iraq be rebuilt when everyone has left? What hath befallen the City of Peace, and where beest its saviours? It feels as if only a shadow, an echo of the Baghdad once praised in the sonorous verses sung by a beseeching Fairuz but a short while ago lingers …

Baghdad, poets and images of the golden age honoured in fragrance;

O, thousand nights and nuptial festivities, the moon cleanses thy visage.

Baghdad, thou journey’st towards glory and grandeur …

* A decisive battle won by the Muslim Arab armies in 636 A.D. against the Sassanian Persians in Qadissiya, Iraq. Majus is a derogatory term used primarily by Arabs towards Iranians, being a corruption of the Old Persian mogh (lit. ‘magus’, denoting a member of the Zoroastrian clergy, from which the English word, ‘magic’, derives).