Stringing pearls in the ‘Pearl of the Gulf': the art of Kuwait’s Mohammed AlKouh

Romanticism and nostalgia are still often regarded as passé in fine art dialogues, as ideas and aesthetics belonging to the 19th century and the chocolate box. But when a tiny, progressive, and unique Arab state produces an artist who is not only one of the rare jewels who hand-colours his images – photographed on an array of vintage equipment – but also so sensitively beguiles his viewers into the rich fabric of the little-known ‘Pearl of the Gulf’, Kuwait, romanticism and nostalgia demand and command attention once again.

Through Mohammed AlKouh’s photographs, one enters a demure world of delicate emotion. Imagery combining Kuwaiti aesthetics – from traditional attire to items from daily life – strikes a chord within the memory of the Kuwaiti. In the Untold Stories series, old-school hand-colouring is accentuated by the artist’s eloquent revival of vintage studio backdrops and the emotional dialogue he forges, which result in a visual poetic poignancy.

The personal is usually, if not always, universal. AlKouh, stimulated by his own emotional development and trials growing up in Kuwait engages in encounters, takes portraits, and provides glimpses of characters and ephemeral events – with, albeit, lifelong impacts – viewers can relate to. He opens up doors with his images that beckon mellifluous emotional responses, and take one to the depths of a country heavily guarded by discretion and modesty. A rare look into hearts that have seldom had ‘windows’ for viewers is presented by AlKouh; and this is what, perhaps, makes him and his work so uncommon and important in the world of contemporary Arab art.

The Rolls Royce Building (from the Tomorrow’s Past series)

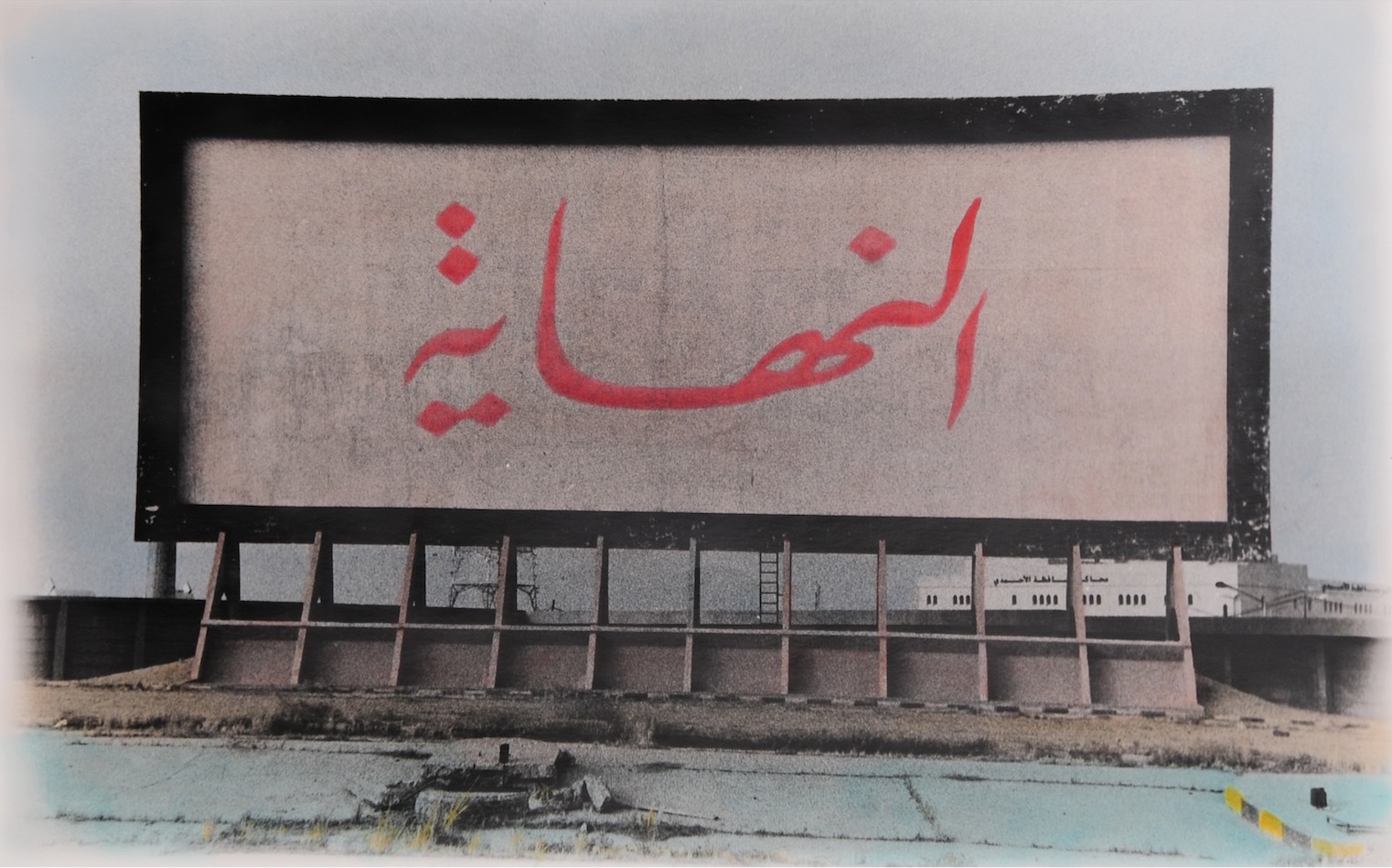

The Tomorrow’s Past series, on the other hand, captures the legacy of a singular architectural history of a country that has never missed style trends throughout the 20th century where buildings are concerned, and that has always displayed a character of its own. From the outdoor cinemas, which many Kuwaitis born before the 90s remember and love, to the iconic blue and white water towers, AlKouh’s instantly recognisable sensitive colouring creates a palimpsest-like account of his country and culture.

Along with emotional maps and architectural documentation are AlKouh’s portraits, possessing the sentiments of the former: unique individuals from a unique state photographed by a unique artist. Legendary individuals such as the artist Sami Mohammed, as well as tattooed eccentrics are all here in a plethora of images: jewel-like revelations from the Pearl of the Gulf.

For whom is your art intended, and what messages does it strive to convey? As well, how personal are your images? Are they all informed by your own stories and experiences?

Art is an emotional expression for me – a way of visualising what I can’t say with words. I show my reactions to what happens around me; sometimes, as a rejection towards change, sometimes in response to someone I’ve lost or do not wish to lose. I find art generally to be an intimate and personal experience. Normally, I can’t work when I’m emotionally stable or happy; something has to move me, strike a chord inside to ignite; so, yes: it all comes from personal experiences.

Orphans (from the Untold Stories series)

What is it like producing art inside Kuwait, and being a Kuwaiti artist in general?

Today, Kuwait is far less active in comparison to the creative movements of the 50s, 60s, and 70s, and is not as much at the forefront of contemporary Arab art as it used to be. I’m very sad to tell you that Kuwaiti artists struggle for the most part. We don’t have an art school here, there are few art supply shops, no artist studios or spaces, and no art fairs, and galleries are closing down –not to mention how hard it is for artists to make their voices heard internationally. On the other hand, artists in the community are very supportive of one another. We have brilliant young minds that need to be nurtured.

When and how did you begin hand-colouring photographs? Why have you chosen to work with such a medium in an age of advancing technology?

I was searching for my voice; I’m a very nostalgic person. I’m torn between two worlds: the world I want to live in, and the world I actually live in. In dreams, you’re always happy and with the ones you love, and no one will ever hurt you. Hand-colouring allows me to be in both worlds, to connect the past with this pre-modern technique. Though my work is contemporary, it addresses the past.

Two Girls in My Dream (from the My Dreams series)

In the past, there existed the belief that photography ‘stole souls’ and kept them in negatives; many were afraid to be photographed. I like to believe that I’m preserving pieces of the people I photograph. For me, the whole process is a ceremony of receiving these ‘pieces’. From the moment I take a photograph, the reflection of the light of my subjects stick to my negatives; then, I process the film with basic earth-based chemicals to reveal their ‘souls’, or interpretations of them; next, I print the images on silver-layered paper using light, and finally, colour them as a celebration of this preservation, adorning and adoring them.

In the past, there existed the belief that photography ‘stole souls’ and kept them in negatives; many were afraid to be photographed. I like to believe that I’m preserving pieces of the people I photograph

Learning this technique wasn’t easy, due to a lack of resources and references. It was once considered a craft done by ‘colourists’, of whom very few exist today. I’ve been to Egypt, Lebanon, Turkey, and France in search of people still hand-colouring photographs, but unluckily for me, most of them have passed away. Serendipity brought me to the remains of some old pigments I experimented with back in 2011, which is when I started teaching myself the art.

The End (from the Tomorrow’s Past series)

Do you consider yourself representative of Kuwait? If so, what do you stand for that is inherently Kuwaiti?

Representing a country is a huge responsibility, and I don’t think I should decide that; it’s something that may come with time. For now, I’m simply showing how I feel about my Kuwait. Kuwait is a beautiful country with a great history. It’s been mistreated by its own people, yet is still standing. We have many great minds who make – and made – differences in our lives, which need to be appreciated and known elsewhere throughout the world.

How do you see your work developing? And, what does it mean to you to be an artist – particularly an Arab one – today?

I photograph only the people I love, and who have an influence on me. During shootings, they add so much to me, and their acceptance of being photographed is an appreciation of my work I feel to be a part of my growth. I feel that my development comes from each subject, and that I will continue to be further affected by such experiences in the future. Let’s see how that will blossom.

Till We Meet in Heaven (from the Untold Stories series)

To be an artist means to be different. Artists tend to think and feel differently, which is why so many feel lonely. This ‘difference’ and loneliness are particular to being an artist. To be an Arab artist today is something quite special. Arabs come from a rich culture, and what I believe to be the most beautiful place on earth; we carry this legacy in our blood. As well, we are emotional people who have always been surrounded by misfortune and malaise, and have witnessed a splendid and troubled past. All of these, combined with current issues in the Arab world, have given Arab artists a vast mine for creative exploration.

Each of us has his or her own unique feelings and life experiences, making us all so special and different. My advice to all is to work hard to show who you are, travel, read, and learn. Be accepting of others and new ideas, and depend on no one but yourself.

The Water Towers (from the Tomorrow’s Past series)

Do you see your work ever exploring the emotional and cultural landscapes of other countries and societies?

I believe in humanity; no matter the differences between people and where we come from, we are all one, whether we like to acknowledge it or not. Art that can move one to tears in Kuwait can do the same in Budapest; one’s personal story is humanity’s story.

The new project I’m currently working on is about love stories in Syrian refugee camps. I went to camps in Turkey and Lebanon in search for the effects of love in such circumstances. I have so many questions about this subject that need to be answered; after all, love unites us and affects us the same, no matter if we live in a palace, or in a small tent on a border between countries.

Cover image: Elisa in a Black Kuwaiti Thobe (detail).