The dazzling life and legacy of Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian

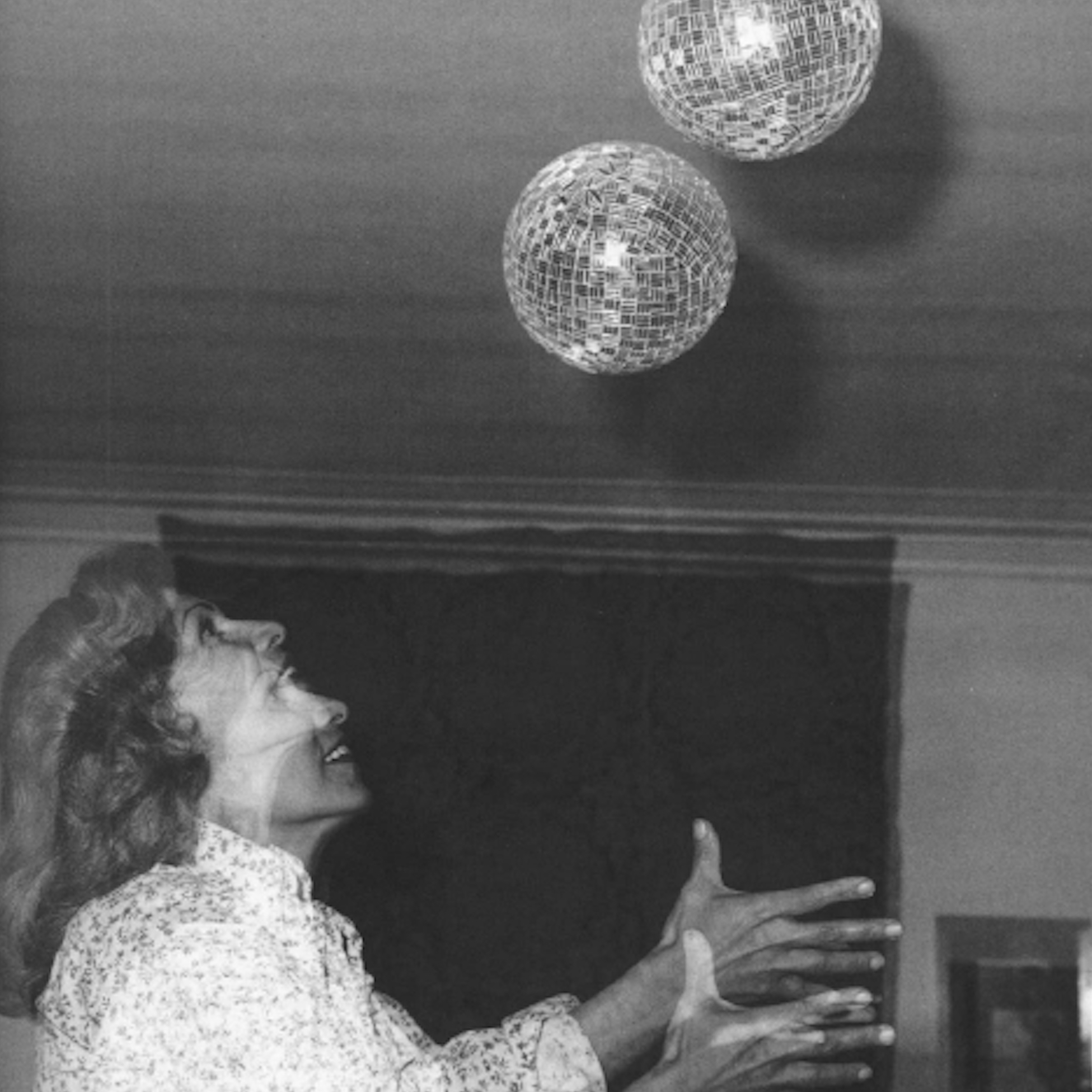

The artist who signs her work simply as ‘Monir’ is a prolific and interdisciplinary figure, whose 70-plus year career is currently being celebrated in a retrospective exhibition curated by Suzanne Cotter at the Serralves Museum of Contemporary Art in Porto, Portugal. Infinite Possibility - Mirror Works and Drawings is the first museum survey of work produced by the nonagenarian between 1974 and 2014, which will also travel to other venues across the world, beginning with the Guggenheim in New York. Undoubtedly a pioneer, Monir is not only the most renowned, but perhaps also the only practitioner working today in the sphere of mirror mosaics. Monir melds in her hypnotic hybrid creations the legacy of traditional Iranian architectural adornment with an awareness of the aesthetics of abstraction and minimalism made popular by her friends and contemporaries in New York in the 60s, such as Frank Stella and Robert Morris. The majority of the works selected have been drawn from the artist’s own collection, and have not been exhibited in public since the 70s. Included are early mirror reliefs on plaster and wood – spontaneous, energetic compositions accented with glimpses of nightingales nestling amid florid bouquets of flowers and fragments of broken Qajar paintings behind glass – and a series of large-scale geometric mirror works that formed part of a solo show organised by Denise René at her gallery in Paris in 1977. The exhibition also features previously unseen abstract arrangements on paper – many of which were made in exile in New York in the absence of a proper studio in the years following the 1979 Iranian Revolution – a series of heptagonal works, four mirror balls (one of which famously lay atop Andy Warhol’s desk until his death in 1987), and a graduated ziggurat-shaped sculpture of particular architectural beauty.

In 1944, at the height of the Second World War, Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian and her three ‘bodyguards’ – her brother, her fiancée, and the latter’s friend – left Allied-occupied Iran on a British liner bound for Bombay. From there, they boarded an American naval ship that took them as far as San Pedro on the West Coast of America, and arrived in New York after four days and three nights on the road. It was Monir’s plan to wait out the war in America and from there, travel to Paris to fulfil her ambition of becoming an artist. The daughter of a man who, although a traditional, conservative Iranian in many respects, had disavowed Islam after the sudden and unexpected death of his mother, and who against all odds was responsible for opening the first girls’ school in his family’s hometown of Ghazvin, Monir was given innumerable and unusual opportunities for a woman of her generation. While the majority of her peers were either considering suitors or allowed to only attend religious schools, Monir was enrolled at the Zoroastrian high school, an institution ‘that today might be advertised as a haven of diversity, attracting Armenian, Jewish, and Baha’i students as well as Zoroastrians, and the daughters of freethinkers of various stripes’, according to her, and subsequently at the University of Tehran as a student of fine arts.

Monir in her studio in Tehran in 1975 (courtesy the artist and The Third Line)

Madame Aminfar, the teacher ‘who made the most lasting impression’ on Monir, was a French woman married to an Iranian who had known Van Gogh, Cézanne, and Gaugin in Paris, and who, in the absence of even books, endeavoured to introduce her students to the works of such modern masters by circulating reproductions of their paintings on postcards. Seduced by Madame Aminfar’s memories of Paris, Monir became transfixed by the idea of studying art in the French capital; and yet, it was New York that was to be her home for the next 12 years. Having spent three months at Anglewood, a private high school in New Jersey, learning English, and attending art classes at Cornell University, Monir enrolled at the Parsons School of Design to study fashion illustration. Her liberal, flamboyant use of colour – ‘turquoise, purple, emerald green, shocking pink, and poppy red’ – set her apart, seeming to those that taught her as a cultural ‘other’. It was whilst still a student at Parsons that Monir began to reflect on the fact that ‘Iran might have something to do with her art’, or that she might have ‘something unusual to offer’. Having or being something unusual to offer was certainly the case when it came to Monir and her fiancée’s roles at the Tenth Street Club’s monthly gatherings, to which Abe Channen of the Museum of Modern Art introduced them. There, they met Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko, Phlip Johnson, and Joan Mitchell, all of whom were also members.

A Parson’s graduate, Monir’s first full-time job was at Bonwit Teller, an upmarket department store on Fifth Avenue, where she was employed to design layouts, which, when completed, were collected by none other than Andy Warhol – who at the time was just another young artist and commercial illustrator whose job it was to devise and produce window displays. Many years later, as Monir recounts in her autobiography, A Mirror Garden, ‘Our paths would cross again under a very different sky’. In 1957, Monir left Bonwit Teller and her life in New York to move back to Iran with her soon-to-be second husband, Abolbashar Farmanfarmaian. Married and with two young children, she took a job at the Ministry of Agriculture, assisting on a project to adapt traditional handicrafts for foreign appeal. It was in this capacity that, upon returning to her childhood hometown of Ghazvin, Monir realised ‘there was history captured in ordinary objects’, rediscovering the magic inherent in relics of the past: painted wooden ceiling panels, panelled Safavid-era doors, Qajar paintings on plaster, paintings on glass, as well as what have come to be known as ghahveh khaneh (coffeehouse) paintings: colourful renderings of scenes from Iran’s national epic, Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh (Book of Kings) that are often used as backdrops for naqqals (storytellers). In Iran, Monir became an avid collector of such remnants of Persian folk art, seeking to preserve a cultural heritage in danger of being lost amid the wreckage of old houses that were being demolished to make way for ‘new concrete boxes’. What she loved about the coffeehouse paintings was ‘their view into people’s souls’, something that her mirror-work of the 70s and onwards would seek to reflect in their multifaceted brilliance.

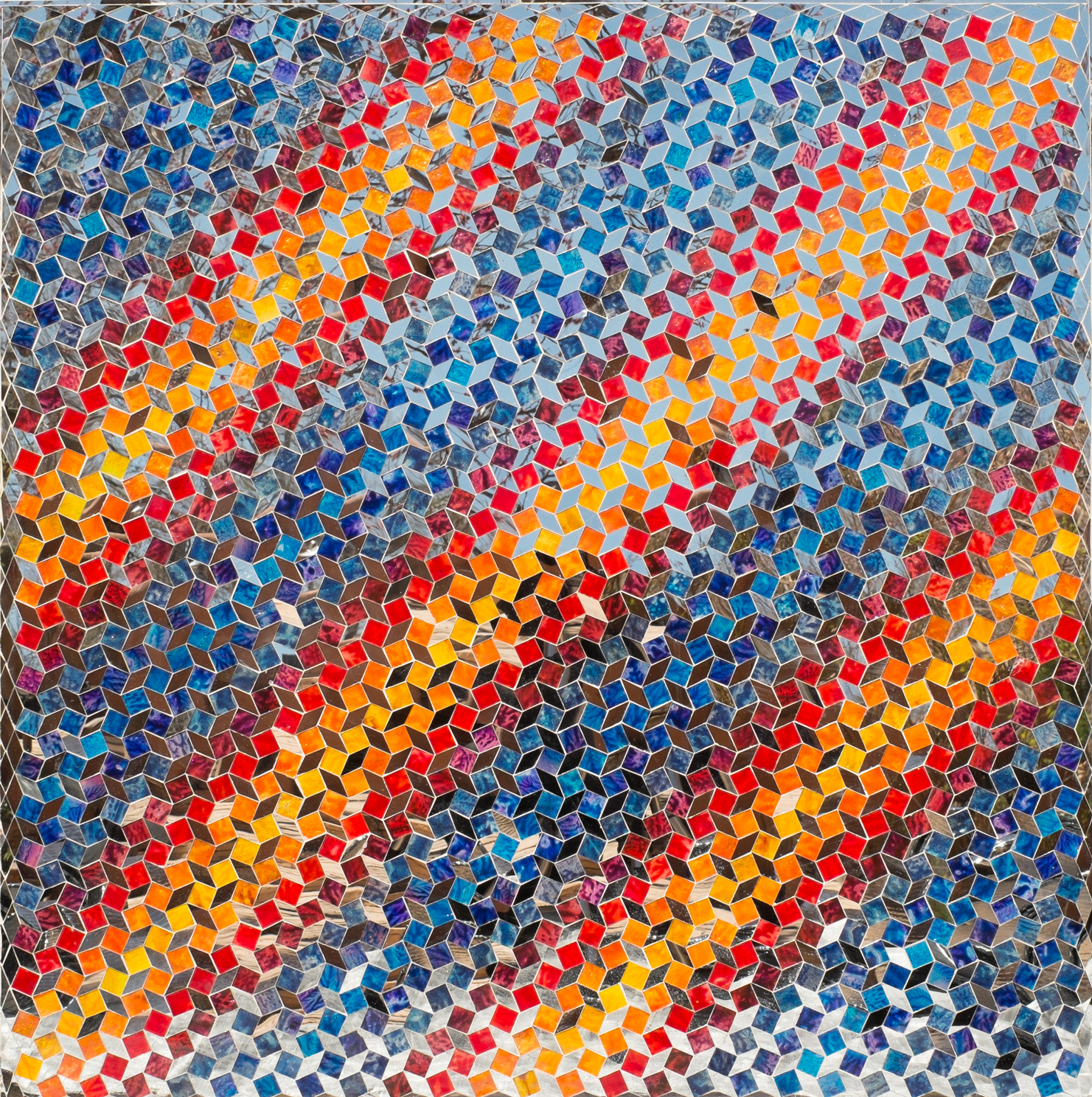

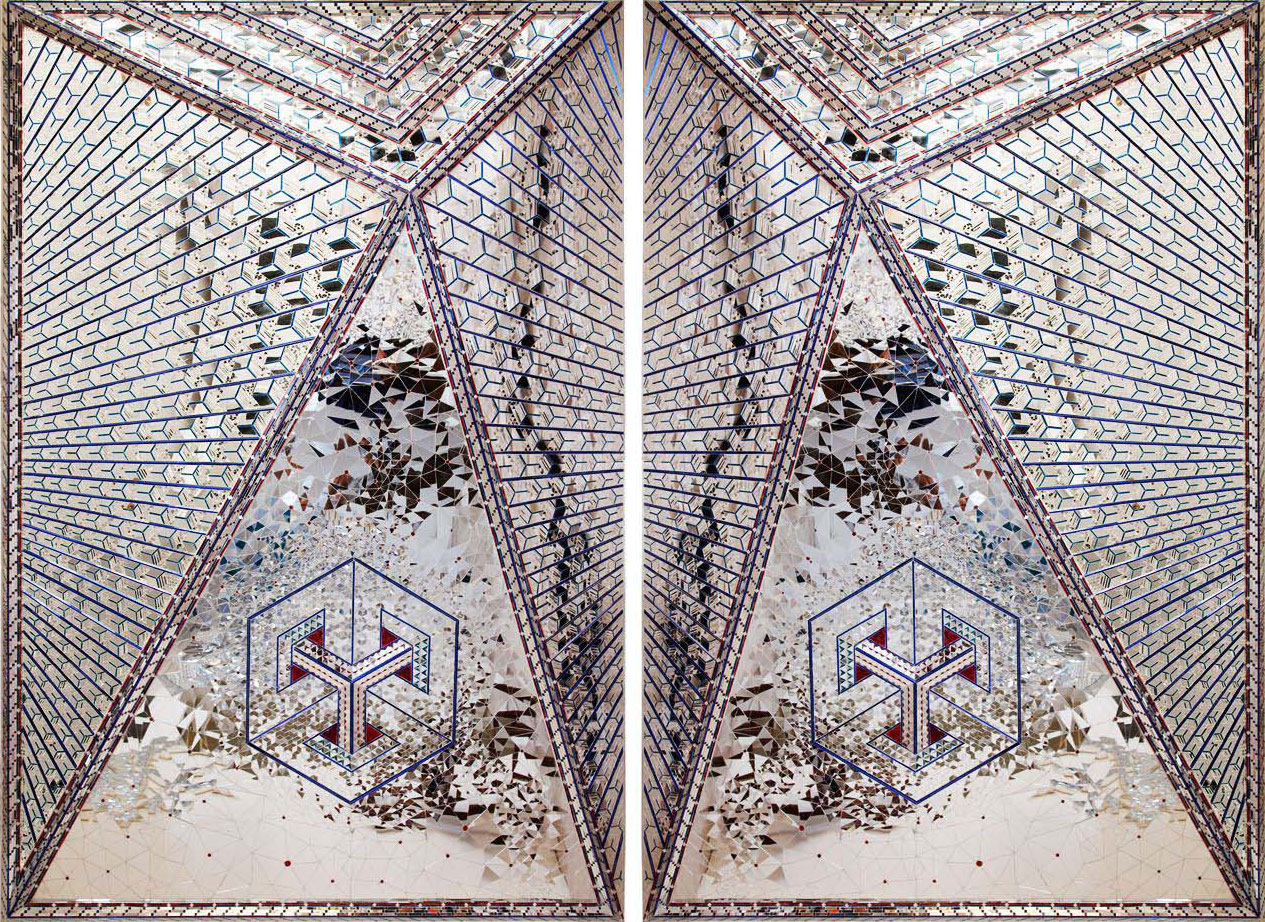

Untitled (1977; courtesy the collection of Zahra Farmanfarmaian)

Wanting to spend more time with her family, Monir resigned from the Ministry of Agriculture after only a few months. After unpacking her paints and brushes – untouched since she had left New York – she began, as she had done as a child, to paint flowers, as well as experiment with monotype printing on canvas and glass. By 1963 she had completed over 100 monotypes, which she exhibited in her first solo exhibition at the University of Tehran. Monir had never shown her work whilst living in New York, except to close friends; nonetheless, the year after she moved back to Iran, she won a gold medal at the 29th Venice Biennale for a group of small, abstract monotype prints displayed in the Iranian pavilion. Seeking always to ‘make it new’, Monir began to play during this time with painting behind glass, making modern day mirages of Qajar-era antiques, many of which – especially those used as architectural decorations – were painted onto square or oval-shaped mirror panels. She sought to reproduce the effect, taking one of her paintings to a mirror factory in Tehran. The finished product, although not unattractive, was far from achieving the desired delicacy, although mirrors in time would come to define Monir’s work in more dazzling ways than one.

The very space seemed on fire, the lamps blazing in hundreds of thousands of reflections. I imagined myself standing inside a many-faceted diamond and looking out at the sun

Monir’s leaning towards mirror mosaics (ayeneh kari), traditionally used to adorn the opulent interiors of Iran’s countless shrines and royal palaces, came about as a result of a visit in 1966 to the 14th shrine of Shah Cheragh (lit. ‘The King of Light’) in Shiraz, in the company of Marcia Hafif and Robert Morris, where, as she recalls in her memoir,

The three of us sat for hours in a high domed hall that was covered entirely … in a mosaic of tiny mirrors cut into hexagons, squares, and triangles … The very space seemed on fire, the lamps blazing in hundreds of thousands of reflections. I imagined myself standing inside a many-faceted diamond and looking out at the sun.

Lightning for Neda (2009; courtesy the artist and The Third Line)

Such an experience, akin to that of ‘living theatre’, proved to be revelatory, leaving Monir determined to incorporate mirror mosaics in her own work. A serendipitous series of events led to the artist’s partnership with the master artisan Hajji Ostad Mohammad Navid. Working with Monir’s designs and under her instruction, the ostad cut stars, triangles, strips, and crescents from unusually fine sheets of mirror manufactured in, and imported from Belgium specifically for the Iranian market. The art of mirror mosaics in Iran originated in the 17th century, when the aristocracy began sending for mirrors from Venice. All too often, the mirrors cracked in transit along the Silk Road, breaking into pieces that were later salvaged by local craftsmen and incorporated into their work, in much the same way as in the creation of tile mosaics.

The geometry of the architectural beginnings of mirror mosaics, as well as in subsequent traditional designs fascinated Monir. Discovering, to her delight, that not only ‘everything is in geometry’, but that the infinite possibility inherent in ‘everything’ might be mapped out simply by using a piece of string rubbed with a little charcoal dust, the artist began to include geometric shapes – circles, triangles, squares, and other polygons – in her creations, extracting clean lines from their origin in such ancient arithmetical arrangements. Her interest in geometry also coincided with a curiosity in Sufi cosmology and the arcane symbolism of shapes in Islamic aesthetic and architectural design. The triangle, for example, represents, in Monir’s words, ‘the intelligent human being’, while the sides of the pentagon ‘are the five senses’, and the hexagon reflects the six virtues of generosity, self-discipline, patience, determination, insight, and compassion. ‘Sol LeWitt had his square … [but] for me everything connects with the hexagon … [it] has the most potential for three-dimensional sculpture’, she writes in A Mirror Garden. And indeed, since the mid-70s, the artist has continued to experiment with augmented hexagonal mosaics and freestanding sculpture, as well as a unique combination of mirror, reverse glass painting, and, in some cases, stainless steel, making work of mesmerising brilliance and beauty.

A kind of magic: Monir in her studio in Tehran in 1975 (courtesy the artist and The Third Line)

Alive with the kinetic potential in the mirror’s power to reflect, and in that of glass to refract, Monir’s works present a world wherein everything is moving to transformative effect. One assumes, when standing before one of her pieces, a central, essentially performative role in invigorating and enervating its surface; and yet, there is a sense, too, that the world as one knows it becomes something of an ‘other’, a fragmented futuristic fantasy of ethereal import. It is an entirely immersive and wonderfully kaleidoscopic experience, which, while ‘it takes your mood’, to quote the artist, encourages new ways of seeing as well as an appreciation of the intangible and transfiguring power of light. Light and life-affirming, unique and yet peculiarly universal, Monir’s work, inherent in which is the legacy of Iranian geometric design elucidated to make art purely for art’s sake, is inspired by her history, her childhood, and the ‘feeling’ of her eyes and her heart.

‘Infinite Possibility - Mirror Works and Drawings, 1974 - 2014′, runs through January 11, 2015 at the Serralves Museum of Contemporary Art in Porto, Portugal.