If Iran ever had a rock and roll dynasty, it belonged to the Qajars

It’s a stiflingly hot and humid morning in New York City. Though I probably shouldn’t, I pour myself another dose of crimson Persian chai in a kamar-barik teacup amidst a din of blaring sirens, whiny horns, scratchy radios, and Manhattan chatter steaming forth from the dirty boulevard below. I’ve got fuzzed-out riffs bouncing about in my head, and am picturing myself sauntering down St. Mark’s Place later in the afternoon before ambling into the seedy corner bar, just like Mick and Keith in Waiting on a Friend. Happily daydreaming whilst timidly sipping my tea, lest I scald my tongue, my cousin and I decide to while away the time by browsing through a mishmash of old, yellowed photo albums, lavishly-illustrated books about Iran, and some artefacts unearthed from her dusty closet of curios. My eyes glance over the panoply of pictures, ceramics, folios, and metalwork arrayed before me, none of which particularly pique my interest; I’m 16, and all I want to do is fall in love, start a rock and roll band, and bury my high school days in the dust. Khayyam? Ferdowsi? Give me the New York Dolls any day.

Just as we’re about to head out to bite the Big Apple, my cousin remembers an old oil painting tucked away somewhere she thinks I’d find interesting. As she blows away the dust accumulated over many moons from its ornate frame, my pupils dilate, and I feel the hair on my legs stand erect; I am, after all, face-to-face with the Pivot of the Universe, God’s Shadow on Earth, the King of Kings, Fat’h Ali Shah-e Qajar, in all his bejeweled and bearded glory. Though I can’t tell my Pahlavi from my Safavi, and have scarce turned a page in the annals of Iranian history, I find something alluring about this figure nonetheless. His look is sinister and haughty, his countenance overbearing and imposing; and, eyeing this hirsute sovereign (Billy Gibbons, go home) with one blessed palm resting on the hilt of a glittering dagger, and the other clutching the tortuous pipe of a gaudy ghalyan, the words on Keith Richards’ now-iconic 70s t-shirt resonate as true as ever: Who the fuck is Mick Jagger?

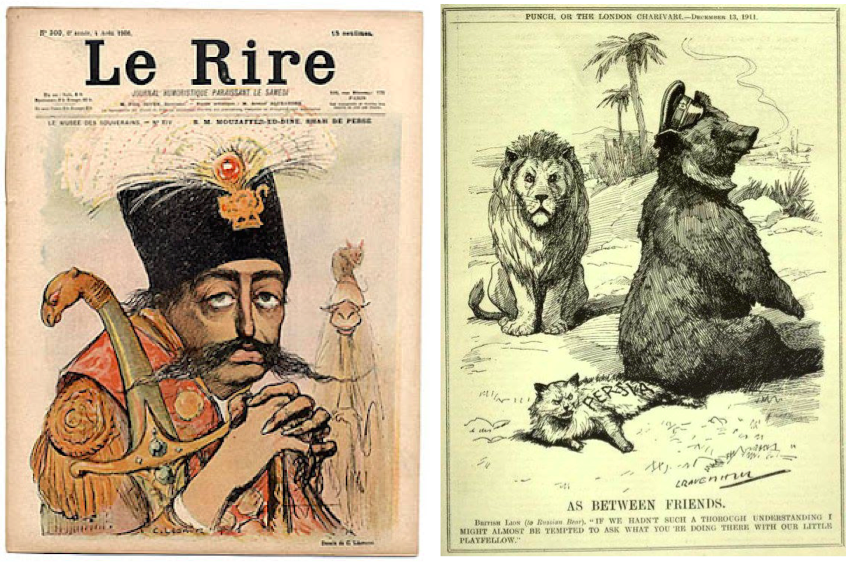

Mozaffareddin Shah as a spineless sovereign on a 1900 edition of France’s Le Rire magazine, and a cartoon depicting Persia caught between England and Russia in the Great Game, from a 1911 edition of Punch, or the London Charivari, which reads: British Lion (to Russian Bear): ‘If we hadn’t such a thorough understanding, I might almost be tempted to ask what you’re doing there with our little playfellow’

My fascination with the Qajars as a teenager, one could argue, was purely superficial, as my knowledge of the depraved dynasty had been garnered from but the extravagant and iconic portraits of amorous wine-imbibing couples, dazzling concubines performing acrobatic feats on hennaed hands, and stern-faced, resolute monarchs, replete with monobrows, fulsome moustaches, and other sundry varieties of facial hair in vogue at the time. In other words, who could have blamed me for falling prey to all those swarthy locks and languid gazes? Why, however, has my infatuation with them continued to wax ever strongly? That the name ‘Qajar’ is synonymous with one of the most degenerate and dissolute of the countless dynasties the land of gol-o-bolbol (lit., ‘flowers and nightingales’) has seen come and go, as well as a rather vile and wretched episode in recent Iranian history is neither hyperbole nor controversy; verily, one need only scratch the surface of just a fragment of the literature produced both during the era, as well as by historians afterwards, such that the Qajars’ legacies may become apparent. If the tales recounted by Ebrahim Beg - the proud nationalist-turned-disillusioned seeker of Zeynolabedin Maraghei’s then-anonymously published novel - do not paint a vivid enough picture, one also has James Justinian Morier’s picaresque classic, The Adventures of Hajji Baba of Ispahan, the woe-inspiring memoirs of Taj ol-Molouk (Nasereddin Shah’s daughter), and the late Houshang Golshiri’s dark novel Shazdeh Ehtejab (Prince Ehtejab), as well as the travelogues penned by literary English luminaries such as Edward Granville Browne, Vita Sackville-West, and Gertrude Bell; all of the aforesaid, amongst other works, provide insight into a world rife with venality, corruption, famine, disease, religious persecution, and humiliating military losses, inter alia, all while fair Persia was being raided by Turcoman marauders in the east, and caught between the claws of the lion and the bear in the Great Game. To cite a passage from The Travel Diary of Ebrahim Beg,

The conclusion from my journey is that in all of those regions of Iran that I saw, no signs of progress or any inclination toward civilisation caught my eye in any of the lands to make me happy … There is no grandiose building with the name of ‘government offices’ in any city. Nowhere can a sign be found of state schools or hospitals … No one cares about the conditions of the mosques … It’s enough that the people have had to immigrate to foreign countries. The cities appear to the eye to be empty of creatures … Today, all over the world, there is none more unfortunate than that Iranian nation … Whence has that misfortune poured into the crevasse of this ancient and noble nation? …

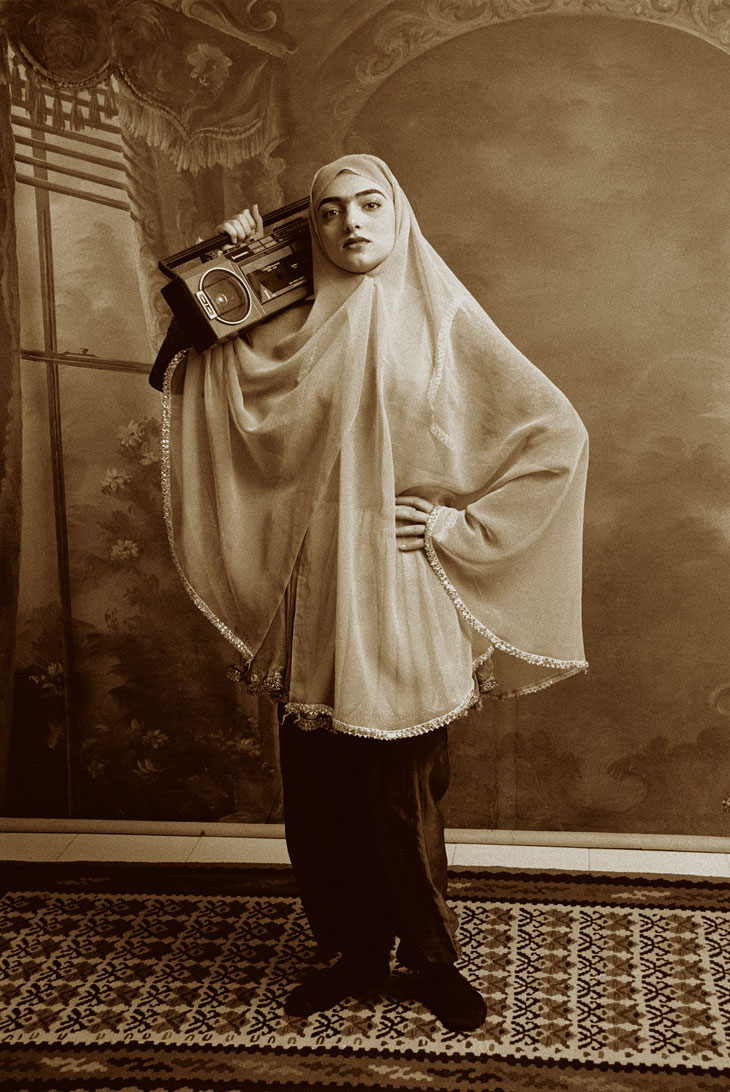

A photograph from Shadi Ghadirian’s Qajar series

The wonder actuated in me for the Qajars, however, is anything but an anomaly. Today, the iconic visual culture that was borne during the tumultuous Afshar and Zand interregnums and reached its peak under the Qajars is visible not only in Iranian visual art, but also in myriad other fields, including music, fashion, and design. Where contemporary art is concerned, the sepia portraits of Shadi Ghadirian have attained classic status; so much so, in fact, to the point that when I proposed exhibiting them in Europe, the affable artist expressed her concern that they had already been shown in various forms (e.g. in exhibitions, on book jackets, etc.) enough times the world over. Whether or not Ghadirian was the prime instigator of a recent inclination towards Qajar aesthetics (the work of pioneer Ghasem Hajizadeh cannot forgo mention here), the fact remains that the world of contemporary Iranian art now abounds with moustaches, abroo-haye peyvasteh (lit., ‘linked eyebrows’), rosy cheeks, and copious doses of bling.

Before ZZ Top, there was Fat’h Ali Shah … and before the likes of Johnny Thunders ever posed snarling with battered Les Pauls in their grimy hands, the Qajars were beating them at their game with tars and setars in their stead, and just as much – if not more – camp and swagger

Two of Shirin Fathi’s series, Heart Throbs, and Harem Babes, Me, and the Lover Boy, see the photographer bedecked in typical (and at times, suggestive) Qajar attire, gazing langorously into the camera from behind kohl-rimmed eyes, in an exploration of gender roles and sexual ambiguity during an age of ‘women with moustaches and men without beards’, as scholar Afsaneh Najmabadi calls it. Similarly, a recent exhibition by Bozorgmehr Hosseinpour provided a glimpse into the harem of Nasereddin Shah – infamous, among other things, for his eccentric taste in [very] manly-looking women – through a number of black-and-white caricatures, while Siamak Filizadeh’s latest series, Underground, retells the life and times of the aforementioned monarch with dashes of humour, pop art aesthetics, and meticulous attention to detail. The art of Ali Chitsaz and Mohsen Ahmadvand are also of note in such a context, the paintings of the former and the mixed media works of the latter both presenting heady admixtures of surrealism, absurdism, and visual elements of the Qajar era, while the works of Ali Alehosseini (also available in t-shirt form through his label, Espanta Design) feature proverbial Qajar figures, as well as icons of the age given a splash of pop art a la Americana.

Ali Rouhani / Jordy Design (available as both a canvas and t-shirt print)

Perhaps to an even greater degree than in visual art, though, has the Qajar aesthetic proven influential in the realms of fashion and design. In the many trendy boutiques dotted throughout Tehran’s more affluent suburbs in the northern parts of the city, one can stock up on Qajar chic aplenty, with imagery from 19th and early 20th century Iran being in vogue once again. One store I visited earlier this year was replete with chinaware embellished with the cherubs so often found in Qajar lithographs as well as calligraphy pertaining to the epoch, in addition to a range of lively cushions in a variety of colours, adorned with the visages of the dynasty’s potentates. What goes around, may one argue here, certainly comes around; as evinced in the writings of Browne and Golshiri, a preferred method of torture (and ‘casual’ execution) during the era was to have portly tormentors lie on the faces of their unfortunate victims, who would suffocate beneath them. Now, one can do the same in style, although such swag seldom comes cheap in the stylish capital.

In addition to such boutiques in Tehran’s swankier neighbourhoods, a number of young, independent designers have also been looking these days to the Qajars for inspiration. Ali Rouhani’s label, Jordy Design, for instance, is well-known amongst Iranian hipsters and fashionistas/stos for its t-shirts depicting typical Qajar figures clutching electric guitars, beer cans, vinyl records, and other similar objects in a very rock and roll manner. Likewise, the moustachioed monarchs have been the subjects of many of San Francisco-based graffiti artist and designer Keyvan Heydari’s (a.k.a. CK1) colourful canvases, from which drip spray paint and psychedelia in equal amounts; and, on a somewhat similar note, the links between the Qajars and rock and roll sensibilities have been pushed to the limits in, not surprisingly, alternative Iranian music. In the video for O-Hum’s raucous, visceral Tehran, Shahram Sharbaf & Co. strike away with wild abandon on electric guitars and a tasteful daf (a type of Iranian frame drum), beneath the coquettish glances of Qajar belles in the paintings above them. The Abjeez (‘sisters’ in vernacular Persian), on the other hand, are somewhat less modest and subtle when it comes to Qajari references, a live television performance in 2007 having seen the group kick out the jams whilst dressed to kill in iconic Qajar garb, doing the souls of the Shah and his furry mistresses proud.

That the Qajars are both in vogue and a source of inspiration for a new generation of artists, musicians, and designers goes without question; although, to return to the question initially posited: what’s there to love about this dynasty, the longtime bane of ‘a people whose natural quickness, intelligence, and aptitude to learn’ caused Nasereddin Shah ‘nothing but anxiety’, to paraphrase Browne? One could most plausibly argue that it is neither the dynasty’s achievements, nor nostalgia for a ‘golden age’ (as is often the case with the Safavids, for example) that today serve as stimuli for young artists; rather, it may have something to do with the fact that the Qajars were some of the most stylish and badass despots to have ever ruled Persia, and the styles of visual art that flourished under their reign among the most iconic and edgy in Iran. Cyrus the Great and the Achaemenids rest atop too high a pedestal to be meddled with (and perhaps, one might remark, understandably so), and, while known for their extravagant tastes in fashion (think earrings, jewelled beards, and eyeliner), their memory largely serves to inspire the likes of historians, nationalists, and Iranologists; the same, likewise, can more or less be said of the Parthians and Sassanians, the images of whom remain but on eroding bas-reliefs, crumbling statues, and various salvaged artefacts. What, however, one may ask, about the Safavids, the last ‘major’ dynasty preceding the Qajars? While they are certainly associated with the oft-celebrated halcyon days of the 16th and 17th centuries, and have had their fair share of influence in the sphere of contemporary literature, there has always been something too sensitive, too flowery, and too exquisite about them.

Setar slingers, androgynes, intoxicated courtesans, and brazen lovers - colourful characters from Qajar Iran

The Qajars, by all accounts, were the genuine bad boys (and girls) of modern Iranian history bar none. Eons before David Bowie appeared haughty and epicene on the cover of The Man Who Sold the World, and later begot Ziggy and the scores of bastard glam rockers that would spring forth from his stardust seed, the Qajars were turning gender expectations and conventional appearances on their heads; before Orange Juice was ripping it up and starting again, the Qajars were doing exactly that, striving at length to overshadow – and at times, physically destroy – all remnants of the dynasties that ruled before them, with as much reverence for Darius the Great as the Sex Pistols had for the Queen; before groupies, there was the Shah’s harem; before Mary Jane, Master Seyyed*; before ZZ Top and Sid Vicious, there were Fat’h Ali Shah and the all-out bad boy prince Zell-ol-Soltan, and before the likes of Johnny Thunders ever posed snarling with battered Les Pauls in their grimy hands, the Qajars were beating them at their game with tars and setars in their stead, and just as much – if not more – camp and swagger.

If Iran has ever had a rock and roll dynasty, it doubtless belonged to the Qajars. Is their influence on today’s Iranian artists, designers, and musicians – amongst other creatives – superficial? Maybe. Does it matter? Not in the slightest; sure, it’s only rock and roll … but I, for one, like it.

* Slang for hashish in Qajar times