The rise, fall, and resurrection of Nasereddin Shah-e Qajar

There’s no escaping him – he’s everywhere. That broad, impeccably groomed moustache, haughty smirk, medallion-studded regalia, black felt cap replete with the lustrous loot of Nader and a telling tuft of peacock plumes, and … those eyes; two dark, sunken spheres possessing at once an air of languor and unbridled pride, which seemingly beckon one from every gaudy teapot and ghalyan in Iran to behold that monarch of late, that Pivot of the Universe. Come, they say; come, and I shall relate the tale of how I, Nasereddin Shah-e Qajar lived, ruled, and died, and recount the fate of fair Persia in days both old and new. Though his countenance today largely adorns chinaware and smoking apparatuses that struggle to evoke an idealised image of a glorious and flowery past when thick, swarthy eyebrows, bawdy ditties accompanied by the jangly sounds of the tar, andextravagant, over-the-top titles were all the rage, the rise and fall of one of Iran’s most iconic monarchs remains ever relevant today.

In the name of God, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful …

Following the decline of the brief renaissance and respite afforded by the Safavids, Iran, yet again, found itself in a state of chaos and confusion. After being sacked by the Afghans, the time was ripe for a new monarch to seize the imperial throne and take advantage of the lost glory of the line of Sheikh Safi. Among the various contenders was one Tahmasp Gholi of the Turkic Afshar tribe from Khorasan in the service of the last Safavid sovereign (hence the Turkish moniker, ‘Slave of Tahmasp’) who, after proving himself to his countrymen against the Ottomans, was elected as Shah of Iran by a grand assembly gathered on the Plain of the Magi. Having ravaged Delhi and successfully routed the belligerent Ottomans once and for all, Nader’s reign on the wrested Peacock Throne was a short one, as was that of Karim Khan of the Zands, who, despite his efforts to bridge the gap between monarch and subject, brought into being a dynasty that contributed a relatively small and uneventful chapter in the massive compendium of Iran’s history. Things changed, however, when Agha Mohammad Khan, another Turkic tribal leader, emerged on the scene. Despite having been orphaned and castrated as a young boy (albeit at the hands of the Afsharids), Agha Mohammad Khan nonetheless mustered the balls (or lack, thereof) to stir a revolt against the Zands, proclaim himself King of Kings, and plunge Persia headlong into one of one of the darkest and most miserable eras it had witnessed in centuries; that was, of course, after he had stripped the boyish Lotf Ali Khan – the final vestige of the short-lived Zands – of his manhood, and blinded nearly an entire city for granting the soon-to-be-eunuch refuge, among other [mis]deeds.

Gone huntin': Nasereddin Shah (far right) with his courtier Malijak (centre) and Etemad-ol-Saltaneh (photograph by Antoin Sevruguin)

Like his predecessors Mohammad Shah and Fathali Shah (Agha Mohammad Khan’s illustriously bearded nephew, to whom his legacy was passed down), Nasereddin Shah was every bit the Qajar: cruel, insatiable, and spineless. However, it was not without reason that he acquired his now-iconic status. In addition to serving as one of the longest reigning monarchs in Iranian history, Nasereddin Shah was also a poet, ballet lover, amateur painter and photographer (indeed, he may be credited with having taken the first selfie), and avid diary keeper. As well, for whatever reasons, he had a predilection for masculine, moustachioed women in tutus (garments that won the monarch’s heart in France), nearly a hundred of which he kept as concubines in his harem.

For all his artistic and womanly (or manly, rather) pursuits, however, his reign was not as rosy as the hubbly-bubblies in Tehran portray it to have been. Like the reign of Fathali Shah before him, under which Iran humiliatingly ceded sovereignty over Armenia, Georgia, Arran (now referred to as the Republic of Azerbaijan), and Daghestan to the Russian Empire through the disastrous treaties of Gulistan and Turkmenchay, so is Nasereddin Shah’s regarded as one of submission towards foreign powers, namely the chief architects of the Great Game: Russia and Britain. In an act of damage control, Nasereddin Shah strove to seize Herat, although he was ultimately forced by the English to relinquish control and recognize the sovereignty of Afghanistan, which Britain had interests in. As well, the royal coffers being unable to provide for his lavish and indolent lifestyle, the Shah looked towards selling almost complete financial, commercial, and military power, as well as concessions as a means of funding. The humiliation and outrage borne by his subjects reached such heights that at one point, in a rather Gandhian move, a fatwa was issued by a cleric against the trade and consumption of tobacco, an industry in the hands of the British, to whom the Shah had granted a monopoly. Despite its flowery outward appearance, Iran under Nasereddin Shah’s rule had reached new lows for which the monarch - as well as the nation - would pay dearly.

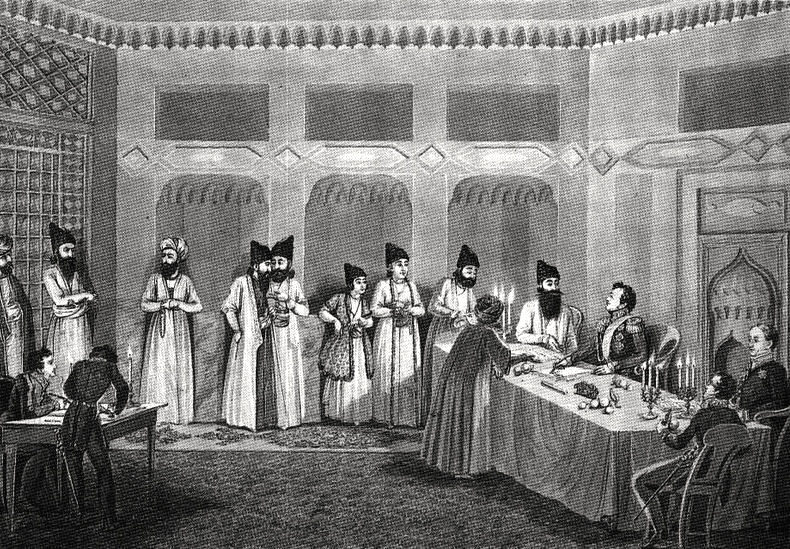

‘Why all the long faces? It’s not as if we’re signing the Treaty of Gulistan!’ Iran’s Abbas Mirza and Russia’s Ivan Paskevich signing the Treaty of Turkmenchay in 1828 (etching by Vladimir Moshkov)

On a typically hot and dusty day in Tehran last May, I emerged from a sooty Peugeot onto a quiet and unassuming back alley with thoughts of canvases, ‘Armenian-style’ sandwiches (which my friend Nazila promised to be serving that day), and air conditioning floating about in my head. After making a few enquiries (beginning with a hesitant ‘Agha!’) from those present – passersby, sweepers, and the like – I found my way to a city named ‘Underground’. There, I witnessed a place ‘as old as despotism’ (according to the text on display), where a king – believed to have made a pact with Azrael, the Angel of Death in Islamic tradition – was assassinated every fifty years, only to rise again from the earth and perpetuate an endless cycle of tyranny, corruption, and decrepitude. Selected for the role of the zombie king was our main man, Nasereddin Shah, Pivot of the Universe, God’s Shadow on Earth, whose rise and tragic fall were depicted in a chronological series of macabre colour prints by Siamak Filizadeh at Aaran Gallery. Though Siamak’s works have by some been compared to those by other Iranian artists who have recently been inspired by episodes and events in modern Iranian history, to place them in the same category would be a mistake. In using the life and times of Nasereddin Shah along with an adapted frame story as the basis of his series, the artist not only wrought a tour de force history lesson, but also a haunting and compelling visual narrative with brooding implications for and references to the present.

The Russians and Brits, they love me to bits …

Beginning with the Shah’s coronation in Tehran, Siamak, with his typical use of humour, references to pop culture, and brilliant use of symbolism and suggestive imagery told of the many trials and tribulations of the Qajar monarch, which culminated in his assassination at the hands of Mirza Reza Kermani and his rusty revolver. No details, however small (gold-plated AK-47s gifted by Saudi princes, anyone?), were spared in the nearly 30 works that were on display on both levels in the gallery, and that featured a fantastic, almost otherworldly cast of characters who all played key roles in the events of the Shah’s life. In one canvas could be witnessed a ghastly, yet blithe Anis-o-Dowleh, the Shah’s favourite concubine, reclining in a tutu (of course) on an art deco sofa with a doll – a symbol of childhood innocence and nonchalance never afforded to her – in her hand. In two other canvases, cynical-looking British and Russian ambassadors lurch over a humbled Shah; beside the British ambassador, the Shah sits austerely in fishnet stockings with a spiked chain around his neck – in reference to a harangue written by the Shah, wherein he likened giving in to the British to being akin to ‘a loose woman who gives in as soon as she is asked to remove her underwear’ – while with the Russian, he gleefully enjoys the tail of a fish as his fair-haired companion greedily clutches the lion’s share of the bait.

Though the zombie king may lie in the parched earth of the shrine of Shah Abdol-Azim, his ardent supporters, sycophants, hangers-on, and other sundry loyalists need not grieve, nor beat their chests in despair; for the Angel of Death is ever true to his word …

As one progressed through the canvases, an air of conspiracy and intrigue began to loom overhead. In a number of works, Siamak depicted the tragedy of Amir Kabir (a.k.a. Mirza Taghi Khan-e Farahani), the revered nationalist Prime Minister who sought to bring about reforms in the country and set Iran on a path of progress and modernisation. According to history and legend, Amir Kabir’s reformist tendencies weren’t held in particular esteem by some around him, and the spineless Shah, influenced greatly by his mother and the then-Chancellor Mirza Agha Khan-e Nuri (amongst others), first demoted Kabir and later had him executed in a bathhouse in Kashan, further darkening Iran’s prospects of salvation from decay and decline.

Now there’s a good lad … (The king’s mother, Nasereddin Shah, and Mirza Agha Khan-e Nuri)

If Kabir’s assassination marked one of the great tragedies of Nasereddin Shah’s rule, the other was undoubtedly his own. Having sold Iran to foreign powers, severely blighted the country’s chances of reform and progress, martyred the leader of a nascent religious movement (i.e. the Bab, whose prophecies would ultimately pave the way for Baha’ism), tried to prematurely introduce newfangled Western notions in the country, championed dictatorship and corruption, and brought about economic disaster (to list a few achievements), the monarch’s wrongdoings soon enough caught up with him. Using historical newspaper articles, personal letters, and other documents as reference material, Siamak illustrated the sordid decline of the Shah. In one piece, the Shah imagines himself as a Gulliver of sorts, being pinned down helpless by his subjects – perhaps the result of a critical letter addressed to him by an anonymous author. Elsewhere, one regardedthe ‘Bread Riots’ that threatened the monarch’s rule, his return from Europe as the personification of materialism and over-indulgence, and the death of the his heir, Amir Ghasem, in a work making direct reference to Michelangelo’s Pieta and causing one to ponder the workings of karma and divine intervention.

If the said events marked the Shah’s slow downfall, the appearance of Mirza Reza Kermani marked his end. A follower of Seyyed Jamaleddin-e Afghani, a political activist and religious figure highly critical of the Shah and his Western tendencies, Kermani’s life took a turn for the worse when, following Afghani’s expulsion from Iran, he became a vocal opponent of the government and fell from ‘grace’ (to be euphemistic). Angry, indignant, and with a pistol in his pocket, Kermani – following, perhaps, in the tradition of Hassan-e Sabbah, the ‘Old Man of the Mountain’ – took the Shah’s life in the shrine of Shah Abdol-Azim in nearby Rey, and after attempting to flee to Ottoman Turkey, was captured, tortured, and executed. ‘Keep this pole as a souvenir’, he is reported to have said before his execution; ‘I will not be the last one’. And, as the tragic hero’s feet dangled from the gallows pole, the light of the sun was made all the more brilliant by rapid bursts of flash in morbid fascination from the sea of smartphones below …

I’ll be back!

Though the zombie king may lie in the parched earth of the shrine of Shah Abdol-Azim, his ardent supporters, sycophants, hangers-on, and other sundry loyalists need not grieve, nor beat their chests in despair; for the Angel of Death is ever true to his word, and the Shah shall yet again drag his imperial corpse from his grave to rule for another 50 years with fear, terror, and unrestrained despotism in macabre splendour and decadence. Yet again shall an ominous shadow loom large over Persia, whose sons and daughters will remain tired and wretched as the sun cowers behind a lion with its tail between its legs. Yet again shall blood be spilled, heroes be sacrificed, and martyrs made, all to no avail, leaving naught to posterity. Alas, at the hour of doom, when all has been lost beyond hope, shall the fallen monarch again utter those selfsame words:

Man bar shoma jur-e digari hokoomat khaham kard, agar zendeh bemanam …

I shall rule thee differently, should I remain alive …

- Attributed to Nasereddin Shah during his final moments