The rise and fall of electro-chaabi, the best thing you’ve never heard

I grew up in the 90s in a wealthy white family in the south of France. I lived in a big house, went to good schools, and had friends called Camille, Guillaume, and Gaëtan. One year, for my birthday, my parents gave me what would become one of my most prized possessions: a portable stereo. Although it was very small and simple, I could tune in to the radio, listen to CDs, and read and record cassettes. A whole new world had opened its doors to me, leading me to discover things I would probably not have otherwise. In a comfy corner of my room, I spent hours listening to radio programmes. For someone who had almost no access to popular culture and wasn’t allowed to watch many things on television, I felt for once like a normal kid from my generation, connected to thousands of others who’d probably had a much different life, but to whom I could relate nonetheless. This little stereo came to radically change my life.

Back then, I wasn’t aware that music was a social marker with the ability to define people and their places of belonging. As such, I alternated between the two main radio stations for teenagers at the time: Fun Radio, with its ‘groove and dance’ songs, and Skyrock, which had just changed its policy to become the first mainstream rap channel in France. I was equally enjoying the melodies of the boy and girl bands and the emerging French rap scene, and embraced one of the latest trends – a musical movement that was not even aired on national radio, but which still gathered enthusiastic crowds for the first time in France: raï. I listened for hours and hours to Algerian singers like Faudel, Cheb Mami, Khaled, and Rachid Taha, whose songs also featured rappers in mixes of hip-hop and North African music.

Everyone had expected me to listen to pop and dance tracks – not raï or rap. Raï (meaning ‘opinion’ in Arabic) to them was exotic and ‘ethnic’, and a strange thing to listen to altogether; but, after all, I was a strange boy with strange interests. At 14, I was trying to learn Arabic by myself, having only a book and the songs of Faudel to practice with. And rap? To those in my family and many others, it appeared as degenerate music coming from the ghettos, which dealt with subjects like violence, prison, and drugs. To them, only gangsters and punks listened to this music with its slang and improper vocabulary. Nobody seemed to understand it, nobody talked to me about it, and nobody ever gave me a rap album as a Christmas or birthday present (the only rap album I had then was one by Menelik, which I had to steal from the company my mother worked at). That my family couldn’t understand my interest in rap and raï was not surprising; but I couldn’t understand why my friends – mostly white and upper-middle class – had the same prejudices and attitudes toward them.

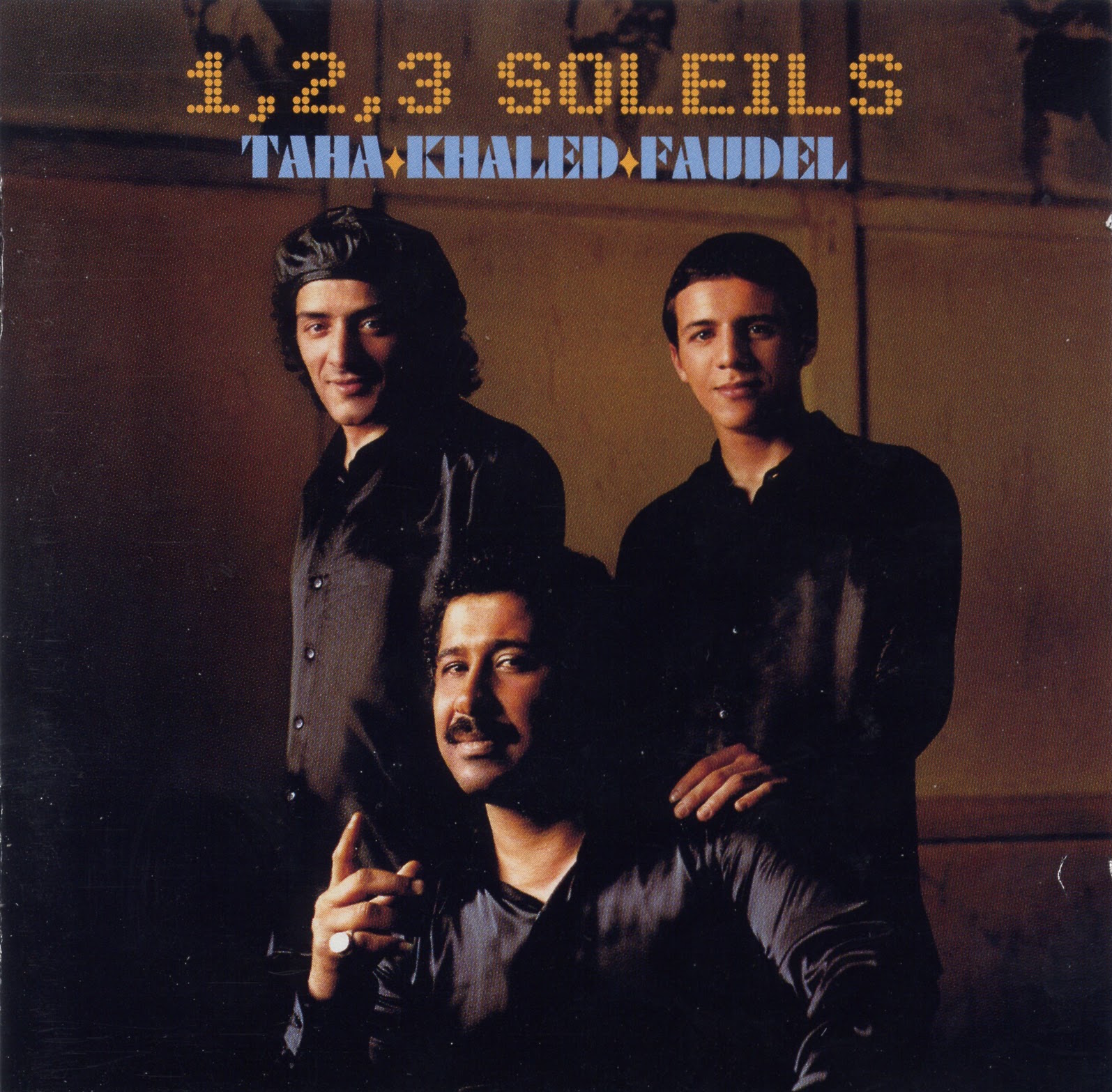

In the 90s, the ‘second generation immigrants’ (the predominant inhabitants of the French banlieues) started taking on a prominent role in French society, and hip-hop was an important part of this movement. Between the Marche des Beurs (‘March of the Arabs’, beur being a derogatory term) of the 80s and the ‘War on Terror’ of the 2000s, the 90s in France was a period of cultural affirmation for peoples such as Arabs and blacks – or, as they were referred to, ‘immigrants’). Ghettos were set on fire, and most of the major cities in France witnessed riots. Films like La Haine (Hatred) and Ma 6T Va Craquer (My City is Going to Crack), as well as rappers such as La Rumeur and Assassin emphasised the racism and misery of France’s minorities. On the flip side, the 1998 FIFA World Cup in Lyon and the 1,2,3, Soleils concert – the biggest ever raï concert held in France – showed signs of the emergence of a more diverse and tolerant generation. If the raï trend rapidly faded away, French hip-hop enjoyed much commercial success. 2002’s Urban Peace concert in the Stade de France was evidence of this, as well as a sign that what was previously something underground had gained the approval of the mainstream. The 90s and early 2000s are now looked back on as a ‘golden age’ of French hip-hop, and today the genre is looked far less at as being ‘ethnic’ or belonging to the ghettos. Today, I can talk about the latest Wati B record with my youngest brother without anyone finding it strange or different.

The cast of La Haine

I now live in a different country – in a different environment, culture, and society. For ten years, I have been based between France and Egypt, where I organise cultural events and write about the connections between these two nations with the aim of improving cross-cultural understanding. I have taken more of an interest in untold stories, trying to understand sociological and political changes, as well as those on an individual level. In the past decade, Egypt has witnessed tremendous changes – socially, culturally, and politically – in which the middle class has played a crucial role. Feeling excluded by the political and economic elite earlier on in this decade, they started to speak out for themselves, as well as many others who didn’t have access to the media or any political representation. At the time, people – rich and poor, Muslim and Christian, men and women – marched side by side, chanting slogans such as ‘Bread, freedom, and dignity’, and today, many are still upset at Egypt’s current state of affairs. The ambitions of many in the middle-class to achieve political power have failed, and as such, they have been looking to culture and the arts. Egypt’s alternative culture scene is now vibrant: there are independent art galleries in middle-class neighbourhoods, indie film screenings, and ‘alternative’ cafés, nightclubs, and lounges, many in the middle class having shunned ‘popular’ forms and venues of entertainment.

A still from Jehane Noujaim’s documentary about the 2011 Egyptian Revolution, The Square

The music scene in particular in the last decade has witnessed significant changes. As with hip-hop in France, many underground movements have been making their way up to the ‘surface’, reaching wider audiences. For instance, genres such as fusion, Oriental jazz, and neo-folk have become trendy in Cairo, with bands performing in large concert halls, at festivals, and even on television programmes and in commercials. They are, however, still backed by independent labels and in many cases, revolutionary. The Egyptian hip-hop scene, however, has had a different trajectory. During the 2011 Revolution and the years following it, it enjoyed a moment in the spotlight, with enthusiastic crowds appreciating the politically-oriented lyrics of rappers; but Sisi’s ‘counter-revolution’ sent hip-hop back underground again, even if it has evolved in many ways since then. Initially having largely Westernised and middle-class origins, it is now more of a marginal phenomenon for the underprivileged – the exact opposite of hip-hop’s story in France.

[Electro-chaabi songs] also spoke about people’s misery, political corruption, and relationships, accurately portraying the lives of millions of Egyptian youth in a way the habibi songs never could

Egypt’s most interesting musical phenomenon of the last decade, perhaps, is mahraganat – ‘festival’ music, or, ‘electro-chaabi’ as it’s called in the West. At the beginning of the 21st century, a new generation of Egyptians with increased accessed to the outside world – as a result of satellite television and the Internet – was looking for change. Tired of the recurrent habibi pop songs (i.e. commercial mainstream Arabic music), many in the middle-class enthusiastically embraced Western musical trends such as rock, jazz, and hip-hop, and mixed them with Egyptian music to form new styles.

Mahraganat duo Oka and Ortega in a still from Hind Meddeb’s Electro-Chaabi

In Egypt’s poorest areas, this eagerness for change was at the origins of the electro-chaabi movement. Completely abandoned by the authorities, the only places where people could find entertainment were at weddings, birthdays, and other celebrations taking place in the streets. In the early 2000s, the electric keyboard began revolutionising these street gatherings, as bands were no longer essential. The first musician to remix traditional chaabi (folk) songs with electronic samples was DJ Weza from Matareya, one of the slums of Cairo, and he was soon followed by others such as Oka and Ortega, DJ Figo, Sadat and Fifty in Sadat City, and Islam Chipsy in Imbaba. The nature of electro-chaabi is almost completely do-it-yourself, as all one needs is a keyboard and a computer to download samples. Like the beginnings of hip-hop, electro-chaabi musicians were divided between DJs and MCs, the former providing the instrumentation and the latter writing lyrics and singing. As the movement began underground, no authorities – neither political nor religious – paid it any attention, which allowed musicians to tackle a number of issues, including some that were very taboo in Egyptian society. The first songs to become famous dealt with subjects such as drugs, alcohol, and women – all of the ingredients for a scandal in a conservative society; but they also spoke of people’s misery, political corruption, and relationships, accurately portraying the lives of millions of Egyptian youth in a way the habibi songs never could.

If this sounds familiar, it should. Exactly like in the case of French hip-hop in the 90s and reggaetón in central and South America in the 2000s, the ruling cultural elite of Egypt was not supportive of electro-chaabi musicians and their audiences. Regardless of their music, one cannot deny the influence and success they have had, or assume that the millions who have embraced the genre have questionable taste. In reality, there is something much bigger linking electro-chaabi and genres like hip-hop, which has to do with culture and the role of the dominant middle and upper classes in it. If art becomes reserved for an elite, then others, perhaps, cannot be judged for creating and spreading their own forms of art using what is available to them. Who is to blame if the people of the slums have never seen a new-wave film or attended a jazz concert? It also becomes ironic when considering that both jazz and French new-wave cinema were the products of rebellion against the dominant artistic conventions of the age, and were widely criticised by the cultural elite for exactly that reason.

Today, electro-chaabi has become omnipresent in Egypt; those of the first generation of musicians are now national icons, and some are even successful businessmen. Even abroad, films such as Hind Meddeb’s Electro-Chaabi (the first instance of the use of the term) have helped these musicians achieve fame and tour in numerous festivals around the world. However, they still have a long way to go to receive recognition from Egypt’s cultural elite, as many of the same stereotypes about hip-hop in the West are being applied to this new musical movement in Egypt; but the case of hip-hop in France shows that it is not always necessarily the cultural elitists who spark revolutions.

Cover image: a detail of a still from Hind Meddeb’s Electro-Chaabi.