Rakı days, rock and roll nights: the life and times of Sait Faik Abasıyanık

Sait Faik had a foul mouth. Or so the story goes. In a televised interview, author Orhan Kemal reminisced about his friend, a faint grin sometimes flickering under a thin, clean-combed moustache. Deadpan and a little nettled, he said:

We really liked each other, and that’s why we were always fighting. I mean, we really went at it. [Sait] always had something nasty to say when I ran into him. ‘What are you doing around here,’ he said [once], and went on [to talk] about my books and stories and said, ‘What’s the point?’ And I said, ‘Yeah, but what about you? Aren’t you an ambassador yet? ‘What’s that supposed to mean,’ he said in a rage. He figured I was making fun of him. He was always a little paranoid. ‘That’s right, chief. An ambassador, you deserve so much. You’re rich and your mother takes care of you, and you studied in France.’ And then he spat out a dirty word I can’t say here. ‘Why not?’ I [asked]. ‘You twerp’, he said, ‘ I didn’t go to France to study French. I went there to eat and drink, travel, and spend money’. And then he let fly another dirty word. And we laughed.

Coffeehouse blues

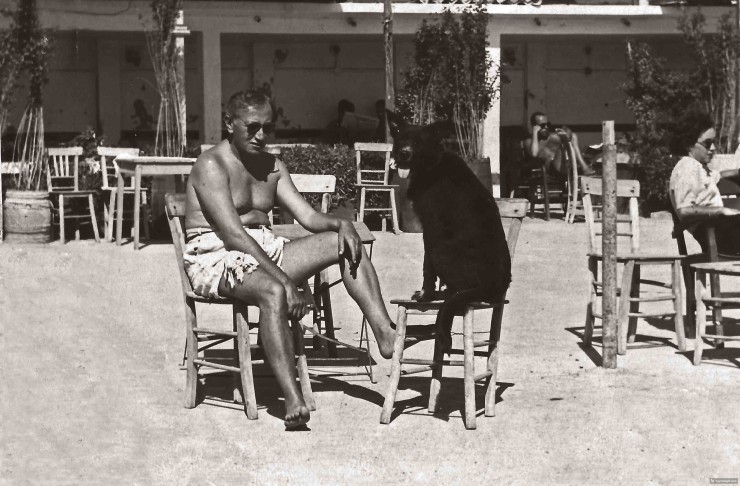

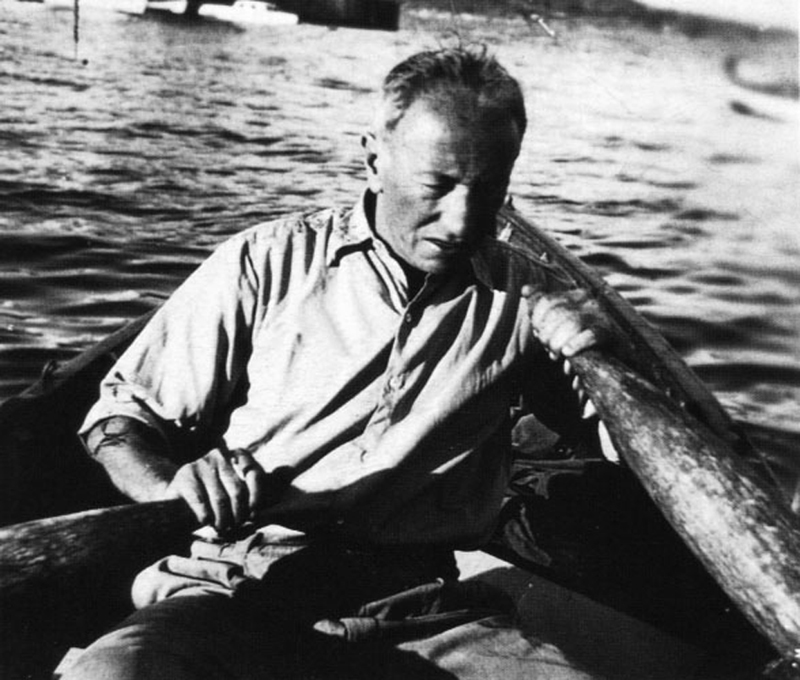

While Orhan’s story is probably true, for many, Sait was a quiet, peaceful, and solitary man, who in his stories depicted the lives of lovers, deviants, idlers, and others belonging to the working class: fishermen, builders, off-the-wall philosophers, sex addicts, lost souls pocketing dreams in old countryside coffeehouses. He was unambitious, perhaps because he could afford to be (his father was a zealous businessman who raked in not a little money selling timber), and, as a writer, he never was looking for fortune or fame. He lived in an opulent family villa – a grand four-story wooden Ottoman mansion not far from the pier on Burgazada, one of the quieter Princes’ Islands, where he took shelter from the crowd and wrote, and enjoyed his mother’s finest dishes (a former maid said he had been particularly fond of a sweet zucchini pie). Life for Sait was about idling with the local fishermen and tradesmen on the island, exploring its quiet corners with his dogs, and boozing until the sun came up with other writers in the bars of Beyoğlu.

Few islanders ever knew Sait was an accomplished writer until the day he died; now, a monstrous statue of him stands in the centre of the main square, a strange twist of fate considering that one of his last stories, I Can’t Go Downtown, tells about his remembrance on his deathbed of the shopkeepers and cronies on the island and their crazy stories, and how he ‘couldn’t’ go downtown. Now, it seems that Sait is condemned to stand there for time eternal. Sait died at the age of forty-six of cirrhosis, the same disease that claimed the life of Atatürk, the father of modern Turkey. Both had a wild passion for rakı, the national Turkish drink known as ‘lion’s milk.’

Lion’s milk, dog day afternoons …

Sait was prolific: all in all, he wrote twelve books of short stories, two novels, and a book of poetry. It was hard to pin him down, however – and that’s probably how he’d wanted it to be. Sait was stubbornly iconoclastic, and favoured pushing the boundaries and letting his imagination run wild, often neglecting the need for an editorial eye. In some of his more mind-bending passages, one wonders how much of his inspiration flowed right from the bottle; but he was arguably a distinct new voice in modern Turkish literature, challenging the dominant trend of social realism. His prose is lyrical and unpretentious, ethereal yet down-to-earth, bold and unforgiving. His stories cover a lot of ground as well: some are set in rural Anatolia, some in Istanbul, and many on the Princes’ Islands. They celebrate the natural world and trace the plight of iconic characters in modern society: ancient coffeehouse proprietors, priests, dream-addled fishermen, poets, lovers, and wandering minstrels. Some are naïvely good-willed, humorously upbeat, drunk on hope and optimism, singing the praises of man and love; but others are sinister and brooding, steeped in loathing and desire. In A Serpent in Alemdağ, he sees a darker side of Istanbul:

Istanbul? Istanbul’s an ugly city, a dirty city – on rainy days, especially. Are other days any better? No. They’re not. On other days, the bridge is covered in bile. Back streets are covered in rubble and mud. Nights are like vomit. Houses turn their backs to the sun. The streets are narrow. The merchants are cruel. The rich are indifferent. People are the same everywhere. Even that one couple asleep on a bed with a gilded frame.

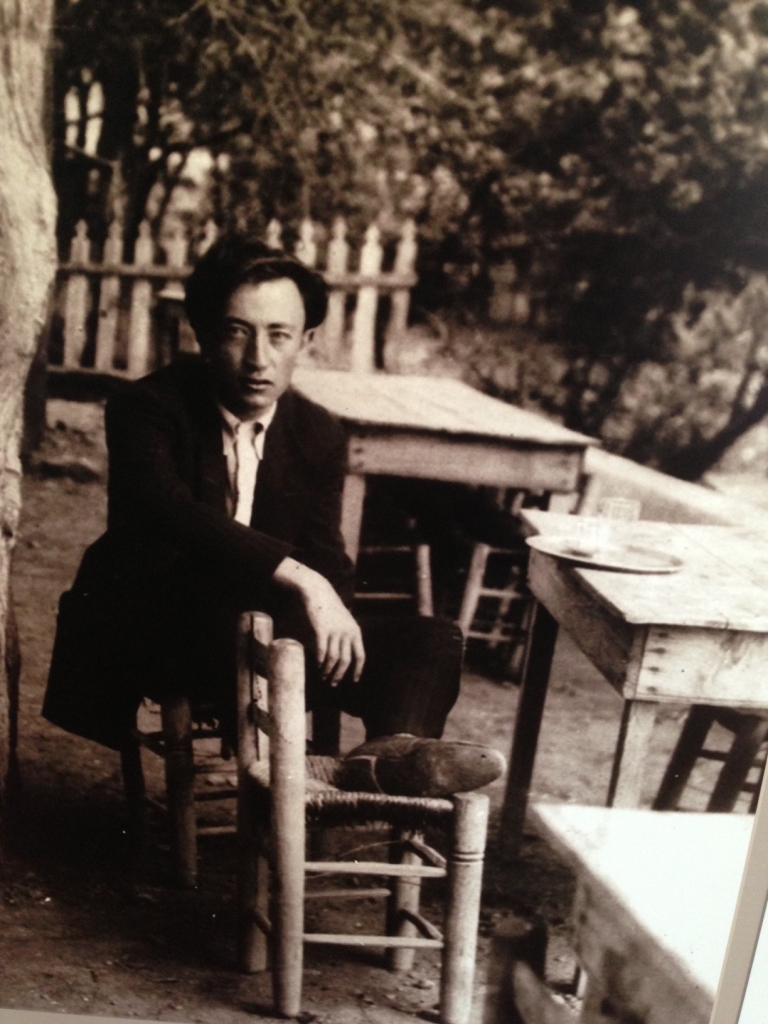

Living the çay life: with fellow poet Özdemir Asaf (centre) and a shiny samovar

In 1953, Faik was made an honorary member of the Mark Twain Foundation, and today many of his stories have been translated into English and other languages. In Turkey, he is widely revered and remembered fondly – one of the most prestigious short story awards bears his name, and many make the pilgrimage out to his family home, now a crisp newly renovated museum; and nearly all of his admirers remember how Sait felt that everything ‘begins with love for another human being’, or how he ‘would go insane if couldn’t write’ – not surprising, given that many of his darker stories dealing with addiction, desire, and violence have either been overlooked or omitted from his canon altogether.

Life for Sait was about idling with the local fishermen and tradesmen on the island, exploring its quiet corners with his dogs, and boozing until the sun came up … in the bars of Beyoğlu

One evening, Sait proposed to fellow writer Leyla Erbil, who promptly slapped him in the face for putting forward what she felt to be a preposterous idea. He suggested they relocate to the Mediterranean coast, where they would run a simple teahouse together: Leyla would brew tea, and Sait would serve the customers, while in the evenings, they would write stories. Perhaps it was only a drunkard’s dream: Sait was almost twenty years older than Leyla, and he was already a heavy drinker when he proposed. The truth is that Sait supposedly snapped his pencil in two and nearly renounced his career as a writer when he discovered Leyla’s brilliance. Not long after Leyla’s rejection, Sait died, and many went so far as to blame Leyla for his death, insinuating that she had driven him to drink. The Kurdish poet Ahmed Arif, who was also desperately in love with Leyla (as much for her brains as for her good looks), assured her that she had nothing to worry about. Leyla had perhaps taken the accusations to heart; she surely had a soft spot for Sait. In a love letter, Ahmed again assured Leyla that she had had nothing to do with Sait’s death, going on to write, ‘A sad, risible, apathetic, indifferent and fearful community, bad wine, and eastern Anatolian food – each dish more poisonous than the next – killed the man.’

Boozing on the Bosphorus

Though almost everyone on Burgazada speaks of Sait’s anonymity and quiet nature, Ahmed called him a ‘tight-fisted egoist’. But still, he reported to Leyla that there were times when Sait would say to him him, ‘My beloved John Dory (a ghastly looking monster of a fish called the dülger that had supposedly been tamed by Christ), my lion, haven’t you turned into that monster yet?’ In his story Death of a Dülger, Sait bemoans a society that mistreats its poets, taming them before making monsters of them. Some say it is a tribute to his friend Ahmed.

In the same televised interview, Orhan Kemal related another one of his run-ins with Sait:

‘But you’re a realist, a social-realist. You just keep drawing out the words if they give you the money, the dialogue and all that …’ [Sait said]. ‘Why don’t you do the same,’ I said. ‘I use my imagination’, he said. ‘We do the same,’ I said, ‘but at the right level, [with] the right amount.’ He thought for a moment. And then he cursed me again.

It will never be known for sure if Sait really had such a foul mouth; but, taking a closer look at some of some of the strange, surreal, rakı-infused, hallucinatory stories of his later period, Orhan might have been on to something. There are, as some would say, limits to the imagination. For the late Yashar Kemal, once regarded as ‘Turkey’s greatest living writer’, ‘Sait not only wrote those sorrowful, intimate stories full of a love for humankind – he also lived them’. For Leyla Erbil, he was a ‘child at heart springing angrily to life, shoving through the dirt that fell over him every day, to challenge death to a duel, and whose anger suddenly subsided the moment he put pen to paper’. Sait was forever pushing back against the walls around him, reimagining boundaries, dreaming of a more inclusive world. His legacy endures in the brave Turkish writers of today.

In memory of Sait Faik Abasıyanık (1906 – 1954).