It was if all the beauty and horror of this wild world had been captured in those few mystifying breaths …

Having finished another chapter of the Turkish paperback novel with a mustachioed Orhan Kemal on the cover, I tossed it aside and laid down on my bed, gazing at a crude, colourful painting of horsemen in the desert. Outside, the purple sky blanketed the smooth roofs of crimson houses, and vestiges of the last hoary notes of the evening call to prayer lingered about in the expanse. Pierre, the quixotic blue-eyed French proprietor with his raspy, jarring guffaws was nowhere to be seen or heard, and I could only barely make out the sound of Ali’s yellow slippers flapping against the dusty mosaics of the riad. My friend had decided to go for a massage somewhere around the bustle of Mohammed VI Avenue, leaving me all alone in the little room, which smelled of smoke and spice. Not that I minded, though; a bit of time to myself after the day’s adventure was much welcomed. We had lost our way in the undulating back alleys of the daunting Djemaa El Fnaa, ending up in a café-cum-brothel beside a jaded Iraqi man who, in between puffs on his patterned serpentine pipe, lamented the state of Marrakech and extolled the writings of Mohamed Choukri, a longtime favourite of mine. A packet of Camel cigarettes we had bought out of boredom the previous afternoon before sipping on cool rosé beneath verdant boughs in the bar near the old church lay on the opposite nightstand, beckoning me for a puff, though I’ve never been one for smokes.

Looking at the painting on the wall in the warm, orange glow of the bulb overhead, I listened to the sounds emanating from the narrow street below, and in the courtyards of the red neighbouring houses. Berber brushed against Arabic in the clamour of children as greasy motorbikes zoomed by, rusty cymbals clinked against one another, and itinerant merchants hawked their panoplies of wares to passersby. The virginity of the place was something to behold; it hadn’t been sullied in the way Tehran or Istanbul had, those concrete jungles with towering skyscrapers, billboards, and pretty girls in sports cars; this was a page from the annals of ages past. Beasts of burden trudged alongside you on sun-drenched streets ponging with the fetid smell of excrement, sweet smoke billowed past handsome countenances, cloaked men with rosaries between coarse fingers gathered together for coffee in dingy haunts, and the day’s destiny lay in the hands of little boys who would hurl imprecations at you when you didn’t buy a trinket from their friend’s shop or stuff a few dirhams into their hands. What unsettled you made you feel like suave Tunner in The Sheltering Sky, and what you found romantic or enchanting like a closet Orientalist. It didn’t feel like the sort of place that time would soften one’s heart towards, or that you could ever become acclimatised to. Marrakech is a temptress to outsiders; she intimidates them, enraptures them, confounds them, devours them whole.

Perhaps it is this very onslaught of the senses, the juxtaposition of the sublime and the disquieting, that has continued to attract luminaries, romantics, and vagabonds (and those all three at once) from across the world. Jean Genet and Tennessee Williams found pleasure in the seedy bars of Tangier and the exotic backsides of doe-eyed catamites; Burroughs and Kerouac in a haven for drugs and drink, and Bowles in the sublime beauty of Morocco’s physical and human landscapes, which would serve as his literary muses from the time he settled there in the late 1940s to the end of his life. And, while the Beatles searched for the otherworldly in India (although Paul McCartney also visited Iran in the 60s), the Stones got what they needed – women, song, and the choicest hashish – in Morocco. The country made such an impression on the tragic Brian Jones that he, quite admirably, recorded the Master Musicians of Joujouka, whose songs were posthumously released on 1971’s Brian Jones Presents the Pipes of Pan at Joujouka. Decades later in the 80s, the Stones made a second trip to Morocco, again finding there musical inspiration with the Master Musicians, which culminated to dizzying effect in the trance-like Continental Drift.

Morocco was not a place that would give you the luxury of forgetting it; it seeped, slowly but surely, into your bones, and burned its image between your eyes

In two days, I would be back in dreary London where the sun never shines. My friend, who had been to Morocco numerous times, said she always swore she’d never come back, yet always soon managed to find herself again in the courtyard of some nondescript riad or other. It may have been my first, but I knew it certainly wouldn’t be my last sojourn there. While it could at times seem somewhat stifling, I was certain that soon I would long for it all: wandering around the streets of Guéliz, my clothes sticking to me and my mouth tasting like dust; trawling the alleys of the grand bazaar beneath a beating sun, looking for a pouf and a cold Casablanca; sitting outside on Mohammed VI Avenue lost in a canvas of blue and orange as the nasal, nostalgia-inducing ballads of Lili Boniche wafted onto the boulevard, and all the pleasures and anxieties of getting lost as a stranger in a strange land. Morocco was not a place that would give you the luxury of forgetting it; it seeped, slowly but surely, into your bones, and burned its image between your eyes.

I rested my head against my stiff, coarse pillow, and ran a hand over the smooth, pink wall. The sounds outside were gradually growing dimmer, and a few stars poked their heads through the swarthy sheet of the night sky. From behind the wall came the faint sounds of a haunting melody played on an old reed flute that seemed at once so close and so far away. The sound transfixed me, and I pressed my ear to the wall, taking pleasure in its coolness against my cheek. Soon, the reed flute was all I could hear; the dulled notes had drowned out the waning chaos of the world below. I opened my door, and looked down at the tiled, idle fountain in the leafy courtyard; not a soul was to be seen, nor a voice to be heard. The warbling sound of the reed grew louder, its languid, hypnotic song enveloping me in sonorous swathes. It was as if all the beauty and horror of this wild world had been captured in those few mystifying breaths, which seemed at that moment to be not the stuff of men, but jinn.

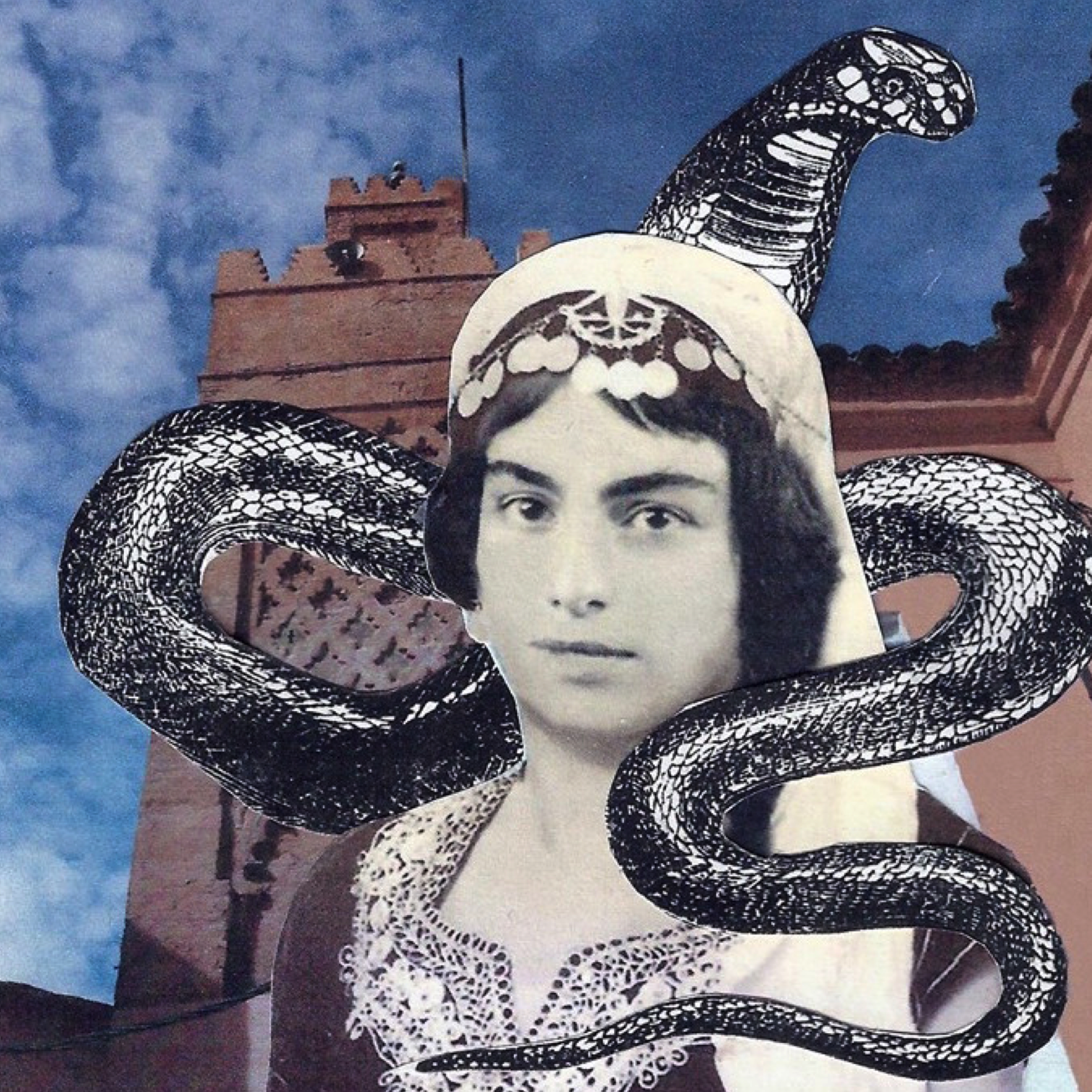

All images from Afsoon’s Smokeless Fire series (Morocco, 2012 - 2013), exhibited at Galerie 127 in Marrakech and featured in her book, Jinns: The Smokeless Fire - Art and Stories by Afsoon, available via www.afsoon.co.uk.