On the trail of oud, from scriptures and souqs to the heart of the jungle

I have known oud for as long as I can remember; it has been present in almost every aspect of my life. The scent was in every sitting I was in – at home, at the houses of my neighbours and relatives, and in every mosque. I remember the scent of oud very well in our local mosque back in the 80s; of course, this was when everyone burnt quality oud. Nowadays, it is only the smell of the best oud that takes me back to my mosque in 1987. I am one of those people who are very sentimental about growing up in the 80s. I love the cartoons, television programmes, and cars of the era; but nothing gives me the feeling of nostalgia like the aroma of a certain type of oud. This very oud has become incredibly rare and expensive to possess these days, and its scent carries a feeling of hope and carelessness that can only be felt by a child.

Constantly having been around that amazing scent since my childhood in Qatar has instilled something deep in my subconscious. Little did I know, however, that I would take it for granted. Growing up, I did not notice the changes in the oud market until I started working with Al Jazeera in 2001 and became independent. I started to realise then how high quality oud had become hard to find, and was doubling in price every few years. Being an oud fanatic made it easy for me to differentiate between choice oud and that of poorer quality, and nowadays, other than the stacks of precious oud gifted to me by my uncle every now and then, I’ve always struggled to find the oud of my childhood at reasonable prices.

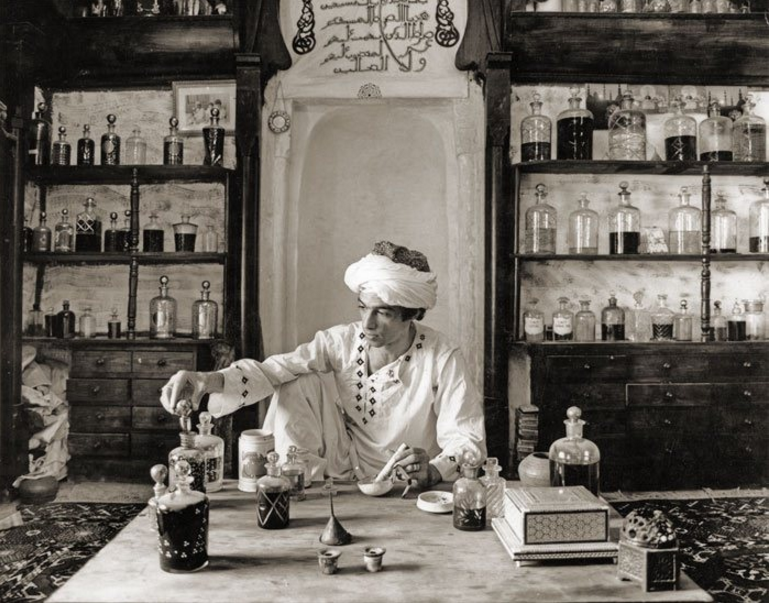

The author burning the ‘most expensive oud in the world’

Around 2008, I began looking at oud from a different angle, wondering about its sources, the factors affecting its supply and demand, its politics, and its transformation into a rare commodity whose price was soaring. That was when the idea of producing a documentary about oud hit me, and when I realised such a project was inevitable. Being in the UK, and having commitments to continuing my education, though, made it difficult to pursue this ambition at that particular moment in time.

In the UK, I have discovered many more dimensions of oud that I hadn’t tapped into during all my years of using it. For example, I have learned about how it reacts to cold climates, as well as different clothing fabrics. Oud has a very ‘hot’ aroma, which explains why it used to make me feel warm when I wore it on my clothes; my thick layers of cotton and wool would absorb its smoke for days. I remember those cold, sunny mornings walking to university in London, when the warmth of the sun, along with the wind and weather hitting against my layered clothes caused the strong scent of my oud to react and rise in the air as a result. Not only was the scent accentuated, but I felt happier as well. I have certainly enjoyed the smell of oud far more in the UK than in my native Qatar.

Hasan Ali Omran producing oud-based perfumes in Cairo in 1981 (courtesy Joseph Hunwick)

I can confidently say that oud is a part of who I am. As an Arab from the GCC, It is inseparable from my daily life and my culture. To put this into perspective, I am a coffee lover, and smelling oud always feels to me like smelling coffee after a long, deep sleep.

The Journey

Oud – or, agarwood or gaharu, as it’s called in other cultures – is a type of strong incense and oil. It originally comes from the tropical aquilaria trees in India and Southeast Asia, but is also widely used in the Arab countries of the Persian Gulf region. In an effort to answer my initial questions about it in the form of a documentary, I embarked on a journey around the world. I knew the trip would be very long and tiring, and I felt tense and uneasy; I wasn’t sure why, though. Was it because of the places I’d planned on visiting, whose jungles and cities I thought could have been dangerous? Or, was it because I thought I might discover things I didn’t want to know about something so precious to me? To me, oud was innocent and pure, and I didn’t want to get more than I’d bargained for. What if I’d found out enough to make me hate the oud trade, and … oud itself?

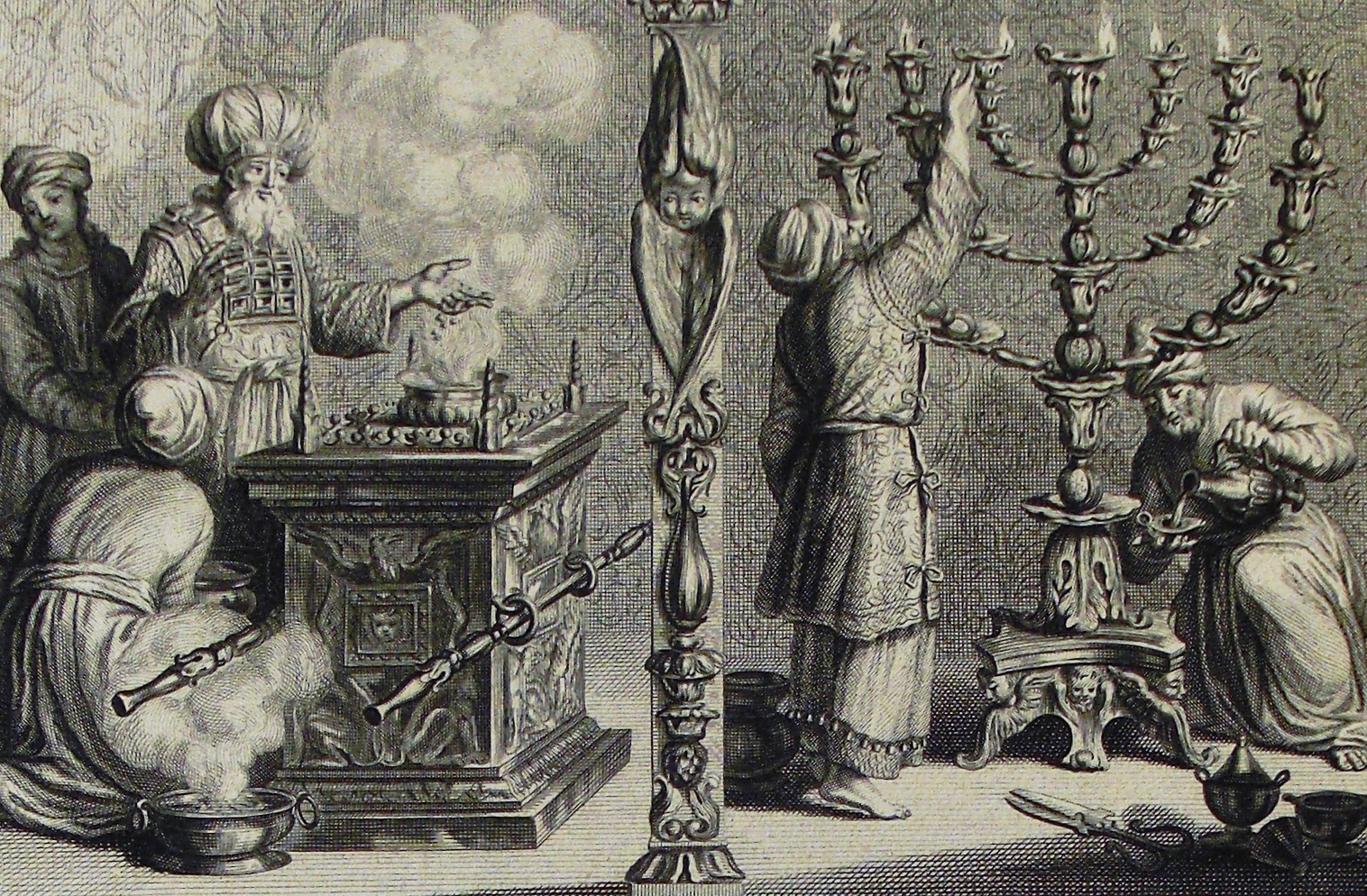

A youth burning oud in a Safavid Persian miniature (c. 1640; courtesy the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art)

Traditionally, oud came to the Persian Gulf through trade between Arab countries and India and China. It has been mentioned in a number of Islamic texts, in addition to having been cited extensively in Arabic literature. I thought, therefore, that old souqs, where the smell of incense is mixed with that of spices and other traditional commodities, would be ideal as a starting point; but, as the high quality oud chips are found in a near-final state in souqs, I had to visit my uncle – one of the few people I know who uses the best oud. I was lucky to find Mr. Khamis, my uncle’s dealer in the souq, who was very specific about the rarity of good oud chips. To obtain this oud – the quality of which often differs – he often has to make several visits to Southeast Asia. The dealer told me about a local oud expert, Mr. Mohammed Aldulaimi, who also assured me that oud was difficult to find, primarily as a result of its rarity and high prices. Both Khamis and Aldulaimi gave me valuable information as to how to find quality oud and differentiate grades; but I was still confused, as the grading system is highly subjective. Therefore, to get to the bottom of the problem, I (like Khamis) had to travel to Southeast Asia, the source of most of the oud in the international market – a fact reinforced by the information provided to me by the Customs Authority in Qatar.

Mr. Aldulaimi’s oud chips (courtesy the author)

Before my travels, I went to find out more about the ‘science’ of oud and its trade in the West. London is my second home; I’m comfortable moving around there, as I’m very familiar with the people and the places. I had been to Arabian Oud – ‘the only specific shop for oud in the UK’, and (according to them) the only place selling actual oud chips in the UK – many times, but never knew they had a VIP room. Coincidentally, I met a Sufi from Ghana in the shop who’d been introduced to oud in the UK. Although it is not traditionally used in Ghana, he told me that he began using it in his Sufi rituals, believing the scent had a spiritual quality that brought him closer to God.

I can confidently say that oud is a part of who I am. As an Arab … it is inseparable from my daily life and my culture

In being determined to identify the geographical connections this valuable resource has made around the world, I was led to the Harrods department store in London. There, I met renowned perfumers who used oud oil in their scents. They spoke passionately about oud, even though it was to them a recent ingredient. It was clear to them, though, that oud had become a new trend, as so many perfumeries are now using it in their most expensive and exclusive perfumes; but to truly understand and appreciate oud, I had to travel to its ultimate source.

Gone pickin': collecting jasmine petals in Grasse, France (courtesy the author)

After a short flight from London, I landed in the historic perfume capital of the world in southern France: Grasse! I’d always associated the south of France with lavender fields; the place, however, was full of jasmine fields, as lavender season had passed when I arrived. According to a French farmer in Grasse, skilled fourth-generation Gypsy women visit the fields between six to nine every morning to pick jasmine. Upon arriving, I went straight to visit Henry Jacque, a passionate perfumer who only produces blends of oils. For decades, Jacque’s perfumery had been exclusive; he used to supply perfumes for only VIPs, including royals and celebrities; but a year ago, he opened a boutique in Harrods’ Salon de Parfums. I was very fascinated by Jacque; modest and highly knowledgeable about oud, he has been a regular visitor to the Gulf countries since the 60s. He shared many insights about oud with me, such as the fact that it took him a quarter of a century to produce a blend containing it, as he believes oud to be a very complicated ingredient.

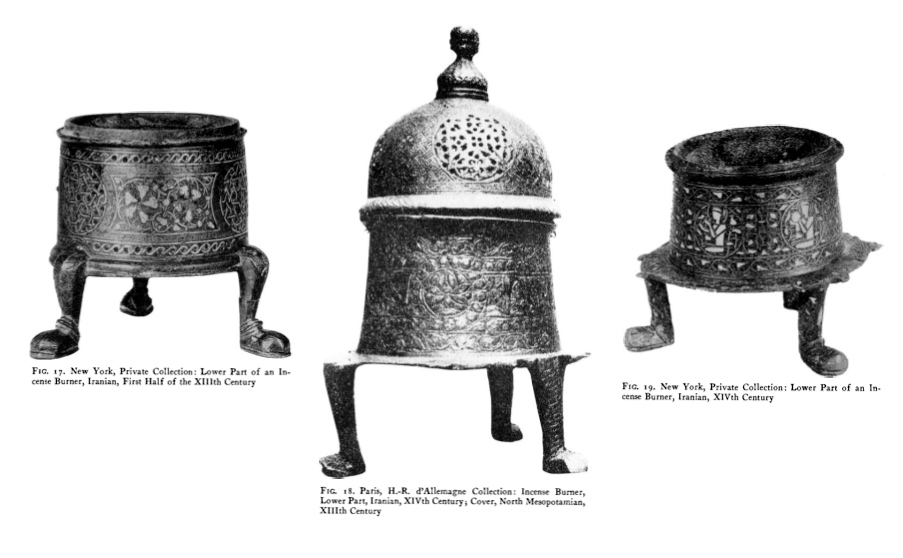

Iranian incense burners from the 13th and 14th centuries (courtesy Mehmet Ağa-Oğlu)

Afterwards, I went to a perfume school, where great ‘noses’ teach the art of perfumery. I’d been a university student for the past five years, but never imagined that I’d sit in a classroom to hear a great French nose explain the properties and types of oud oil! The nose was equally excited to meet such a heavy user of oud as myself. Swamped with information on the oud market in the West, I wanted to know more about the science of oud, and so planned to go back to London to meet Joachim Gratzfeld of the Botanic Gardens Conservation. But before I left France, I got in touch with a very interesting individual – a French oud expert who hunts for only the best oud chips around the world with particular and passionate customers. Alan Mahaffey was introduced to oud as a child, as his parents worked for the late King Fahad bin Abdulaziz of Saudi Arabia. Alan is not what I’d call an ordinary person; he’s quiet and secretive, perhaps as his trade in high quality oud is mysterious by nature. I brought some oud chips with me to see what Alan thought of them. He immediately recognised their shape, but I had to burn them for him so he’d be able to give me his opinion of their grade. We agreed to meet a week later, in Thailand.

A Bedouin woman burning oud in Saudi Arabia (courtesy J. Lewis)

Back in London, Gratzfeld supported the claim that all agarwood trees are endangered to some extent. It was educating to discover the origins of a commodity harvested from India to Indochina, Malaysia, Indonesia, and even Papua New Guinea. The professor took me to the herbarium containing many types of aquilaria trees, and explained how oud is formed. One in every ten trees is wounded (by animals, storms, etc.); afterwards, the wounds provide an open door to bacteria and insects, which incite the tree to defend itself by producing antibodies in the form of agarwood. So far, the trip had only made me even more curious to know about the wild jungle tree.

My first stop in Southeast Asia was Thailand. For millennia, oud has had spiritual associations in many Southeast Asian cultures, its smoke being said to aid contemplation. It has been mentioned in some of the world’s oldest texts (e.g. the Sanskrit Vedas), and also appears in the Bible, the Torah, and Islamic scriptures. I was supposed to go to a national park to see a tree in the wild. Coincidentally (and unfortunately), there had been some trouble in the jungle, where shooting between park rangers and agarwood poachers had led to the death of a ranger. Because of this, I didn’t get to see it.

An illustration from the Phillip Medhurst Picture Torah

This was the first clue of the danger surrounding the oud trade. At the funeral of the fallen ranger, I met with government officials and other rangers, who talked about steady illegal logging, and the endangerment of the agarwood tree as well as others. I later visited Bangkok, where illegal oud chips are sold publicly, suggesting not only a huge market for it, but also corruption. To document illegal practices, I had to take with me a secret camera. I remembered what a major oud dealer had once told me: when you start asking questions about the oud business in Bangkok, you’d better look over your shoulder! I had never been in a dangerous situation like that in my life; but my curiosity was stronger than my cautiousness. I disguised myself as a wealthy client, and was invited to a private flat, where oud had been piled on the floor and was being sifted by shady individuals. I could tell it was the ‘good stuff’, and they comfortably told me that they’d sourced it from India, Myanmar, and Cambodia – the same countries that have a ban on exporting wild agarwood. It became clear to me that the oud trade was not only harming nature, but also people. But, I thought, as the harm was only being done in places where the tree is nearly extinct, and as all of what I buy comes from Indonesia and Malaysia, I might not have anything to feel guilty about.

The author (centre) standing before the 200 year-old agarwood tree in Thailand

I was happy to meet Alan in Thailand. There, he introduced me to one of his friends, who was kind enough to show me agarwood trees and the process of distilling oud oil. What was really amazing, though, was a trip to a 200 year-old agarwood tree, full of resin. To add to its magnificence and the dodgy side of the oud business, a whole regiment of the Thai army protects it. A Japanese company had made an offer to purchase the tree for $23 million, which might make it the most expensive in the world; but, as amazing as it was, it wasn’t enough to feed my curiosity. I needed to see the agarwood tree in the jungle itself.

The final stop on my travels was Malaysia. I got in touch with a member of the native forest people, the Orang Asli, who took me on a day trip deep into the Malaysian jungle. It was hot, humid, and of course, very dangerous. Nevertheless, it was worth it, as I eventually managed to see the agarwood tree in the wild. It was also a very sad experience, as the Orang Asli have so few trees that they have to harvest them earlier, resulting in lower quality agarwood. The Malaysian market, however, seems to be relatively stable. Most of the wild agarwood being sold is harvested legally, suggesting that the oud trade is less problematic in Malaysia, despite the illegal Indian, Sri Lankan, and Burmese agarwood being sold there.

My journey, all in all, was beyond belief on so many levels. I had the opportunity to link East and West, and North and South, as well as uncover the stories surrounding a magnificent natural resource and observe the dynamics of its market. As for oud itself, perhaps everyone who consumes it is a part of the problem to some extent, as its demand far outstrips its supply. The question, some may argue, is how to preserve the rich cultures that have thrived on this resource while safeguarding its life in the wild as the same time.

Cover image: Tareq Sayed Rajab de Montfort - A Midsummer Arabian Dream (detail; courtesy the artist)