Songlines’ Editor-in-Chief has a heady experience or two in Konya, Turkey

The city of Konya in Turkey is a place of pilgrimage, drawing visitors from around the world to the shrine of Jalaluddin Rumi, the 13th century Persian Sufi poet and mystic from Balkh, Afghanistan, and inspirer of the Mevlevi (Mowlavi) order of Sufis, popularly referred to as the ‘Whirling Dervishes’. Rumi’s idea of finding the ‘Beloved’ through the human heart, and his message of tolerance seem particularly relevant today, given the Islamic State crisis lurking nearby on the Turkey-Syria border.

The number of visitors to Rumi’s iconic, conical green mausoleum reaches its peak during the annual Shab-e Arusi (Persian for ‘Wedding Night’), which takes place between December 10 – 17 to mark the mystic’s death, or, alternatively, his union with his Beloved in 1207. Unlike most other Muslim festivals whose dates are determined by the lunar calendar, the Turks have fixed the date of his death as December 17 in the Gregorian calendar. Rumi’s shrine attracts not only Muslim visitors, but people of many other faiths from around the world as well. During the festival, big sema ceremonies (recitations of Koranic verses, along with music and whirling) held in a specially-built building, as well as more informal musical gatherings and sessions in hotels and other venues throughout the city.

December in Konya, however, is bitterly cold, and the warmer period of late September – certainly a more appealing time for visitors – sees another celebration, the Mystic Music Festival, which ends on the 30th of the month each year, falling on Rumi’s birthday. The most recent edition, which ran from the 22nd till the 30th of September, was the 11th, and included performing artists from Iran, Tajikistan, Pakistan, India, Indonesia, Comoros, Bolivia, and Spain. ‘Rumi used to love music and uniting people; the Mystic Music Festival [brings] these together’, said organiser Feridun Gündeş. The concerts are free, and take place in a concert hall seating around 750 people, which is usually full. ‘Many of the most enthusiastic listeners [of] this music are in Europe and the US, and we want to create that [sort of] audience here’, he further remarked.

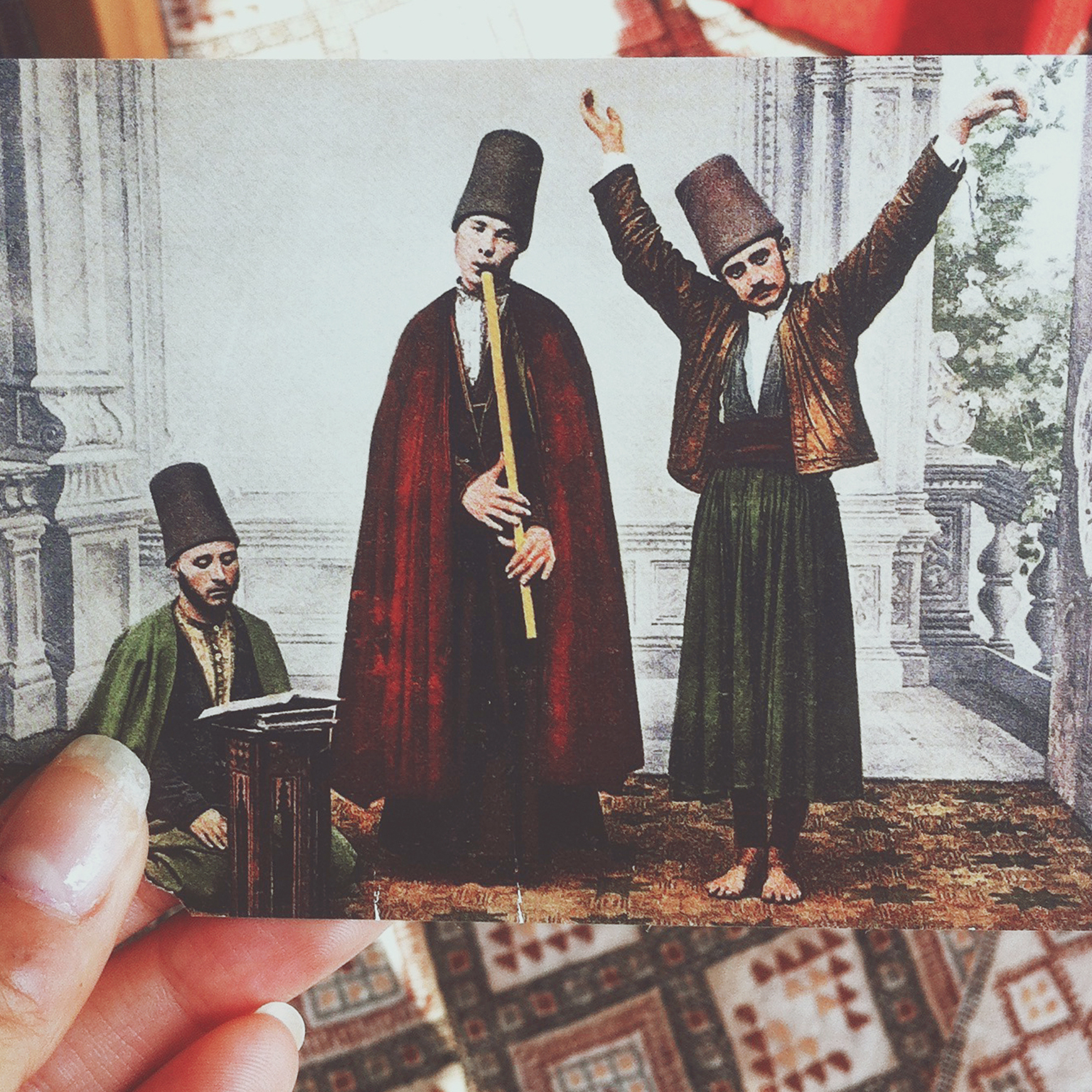

A late 16th/early 17th century Ottoman miniature depicting the meeting of Rumi (left, with black cap) and Shams of Tabriz (on horse)

The majority of the performers for the 11th edition came primarily from Muslim countries, although the Spanish group, Resonet, brought Christian music from the church of Santiago de Compostela, which, interestingly, was consecrated around the same time as Rumi’s death in Konya. A pre-Christian world, on the other hand, was evoked by the singing of Bolivia’s Luzmila Carpio, who performs songs by the indigenous Quechua and Aymara people accompanied by panpipes and flutes, as well as music for Christian celebrations; most remarkable, however, are her bird-like vocals, which truly sound like a force of nature. From Pakistan, Sain Zahoor is a true Sufi minstrel who has performed for years at shrines in Pakistan’s Punjab province, specialising in the poetry of the 18th century Bulleh Shah, who, like Rumi, spoke of the love of – rather than the fear – of God, and decried religious dogma. Dressed in colourful clothes, he plucks a brightly-tasselled ektara (Persian for ‘one string’), and swirls between verses, stamping his ghunghroos (ankle bells). It is in seeing Zahoor perform that one can really understand the power of this sort of music to move hearts.

For [Kayhan] Kalhor, as well as all the other performers, a visit to the shrine itself was a highlight of the festival, being both a sacred site and a museum with interesting artefacts related to Mevlevi music, culture, and beliefs … The feeling of a dedicated community of humanistic people is something that is very well-represented throughout the museum

Less interesting, however, was a group I was most interested to see: Seni Budaya Nusantara from Aceh in Indonesia. Apparently, their dances were based on some sort of local tradition, but it was so unfortunately lost in the precision choreography of the dancing girls, the glitzy costumes, and the showbiz aura of the spectacle, that whatever spiritual roots it may have had were lost, despite the many divine invocations. This, perhaps, revealed misunderstandings in much of the world about what this group wants to export, and what they think an international audience might be interested in. The Indonesian organisers presumably thought that his Bollywood-esque version of their local traditions would have great international appeal. Quite the contrary, it looked like a tourist show. I’m sure there are great Sufi music groups in Indonesia that would have a welcoming audience in the West, but I’ve yet to see any.

Unlike the Indonesian troupe, Sain Zahoor was such a hit, because he seemed like someone plucked from a village or local shrine, coming across as the genuine article. His producers, however, could have presented his show much better to make it look more professional on stage and to more effectively convey the meanings of his songs to audiences who didn’t understand Punjabi. When I met Sain a few years ago in Lahore, he told me how he’d been troubled by a recurring dream as a child; he saw a hand beckoning to him from a grave, and he sleepwalked to try and find it. His parents took him to various local experts to cure the problem, but it didn’t work. In the end, he left home aged around 10, to go and find the grave that called him in his dreams. Several years later, he recognised the shrine at Uch Sharif, the ‘City of Saints’ in Punjab, and when he arrived, someone greeted him and said they had been waiting for him. From then on, he dedicated himself to Sufi music and spreading the words of mystics like Bulleh Shah. Some verses of Difficult Paths, one of Shah’s most popular poems, as sung by Sain, read:

Engrossed in God, love erases being;

Love’s fire unites the lover with the Beloved.

Like Bulleh Shah, I dance to the tune of love;

The paths of love are long and difficult. Allah-hu …

Sain Zahoor and the others aside, the most popular concert of the festival was that of Kayhan Kalhor, the internationally-renowned kamancheh player from Iran, and a group of Iranian musicians who performed music to poems by Rumi. The concert hall was packed, with people crowding onto the steps in the aisles; some had even come from Iran to hear Kalhor perform, as he hasn’t given a concert in Iran since 2009.

For Kalhor, as well as all the other performers, a visit to the shrine itself was a highlight of the festival, being both a sacred site and a museum with interesting artefacts related to Mevlevi music, culture, and beliefs, and accompanying texts in both Turkish and English. It’s clear how important the kitchen was in Mevlevi culture, not just for supplying food, but also in giving a hierarchy of roles in the community, from ‘keeper of the fire’ to head chef. The feeling of a dedicated community of humanistic people is something that is very well-represented throughout the museum.

Altogether, the Mystic Music Festival holds great potential and attraction for international visitors. I met people coming from Birmingham in the UK for the second time there; and, as part of a wider trip, Konya is a good starting place en route to other sites in Turkey, such as Cappadocia, known for its otherworldly landscapes and Byzantine churches. Perhaps one of Rumi’s most cited verses stands as a suitable invitation to Konya and the festival held in his honour:

Come, come, whoever you are,

Wanderer, worshipper, lover of leaving;

It doesn’t matter.

Ours is not a caravan of despair -

Come, even if you have broken your vows a thousand times;

Come, yet again, come, come.

- An inscription in Rumi’s shrine in Konya, adapted from Persian into English by Coleman Barks