Capturing the complexities of the Egyptian Revolution in black-and-white photographs

A revolution, an election, and a coup. All within three years.

At a recent soirée, I met an individual who evidently seemed perplexed about the condition of Iran and his fellow countrymen back home. Speaking softly, yet with not little agitation, the veins on his neck and forehead produced a rather interesting topography, while the hue of his face began to surpass that of the bulbous glass of cabernet sauvignon twirling around in a hirsute hand. He looked at me unflinchingly, with a glimmer of madness in his deep brown eyes, as he gave me the lowdown. ‘First, the Shah. Then, Mossadegh. Then, a coup. Then, the Shah again. Then, a Revolution and an Islamic Republic’, he said, as I bit my lip to stifle an oncoming smirk. ‘What other country have you seen that has experienced all of this within half a century? None. Why can’t we just make up our minds? We’re fucked up. Fucked up!’

The fellow obviously hadn’t been following the recent events in the Arab world in faraway USA. These are times of change, upheaval, destruction, violence, and renewal; as the Iranian photographers Bahman Jalali and Rana Javadi would have called them, days of blood, days of fire. From behind my desk in Toronto I watched the demonstrations in Cairo, Mubarak’s deposition, the coming of Morsi, and the speeches of Sisi. I watched films about post-Mubarak Egypt and documentaries about the Revolution, flipped through the pages of books about revolutionary street art and firsthand accounts of unrest in Cairo, and listened to musical responses to the Egyptian situation. I observed the passion, fear, and disillusionment of my Egyptian friends on social media, how hopes were alighted, maintained, and later dashed.

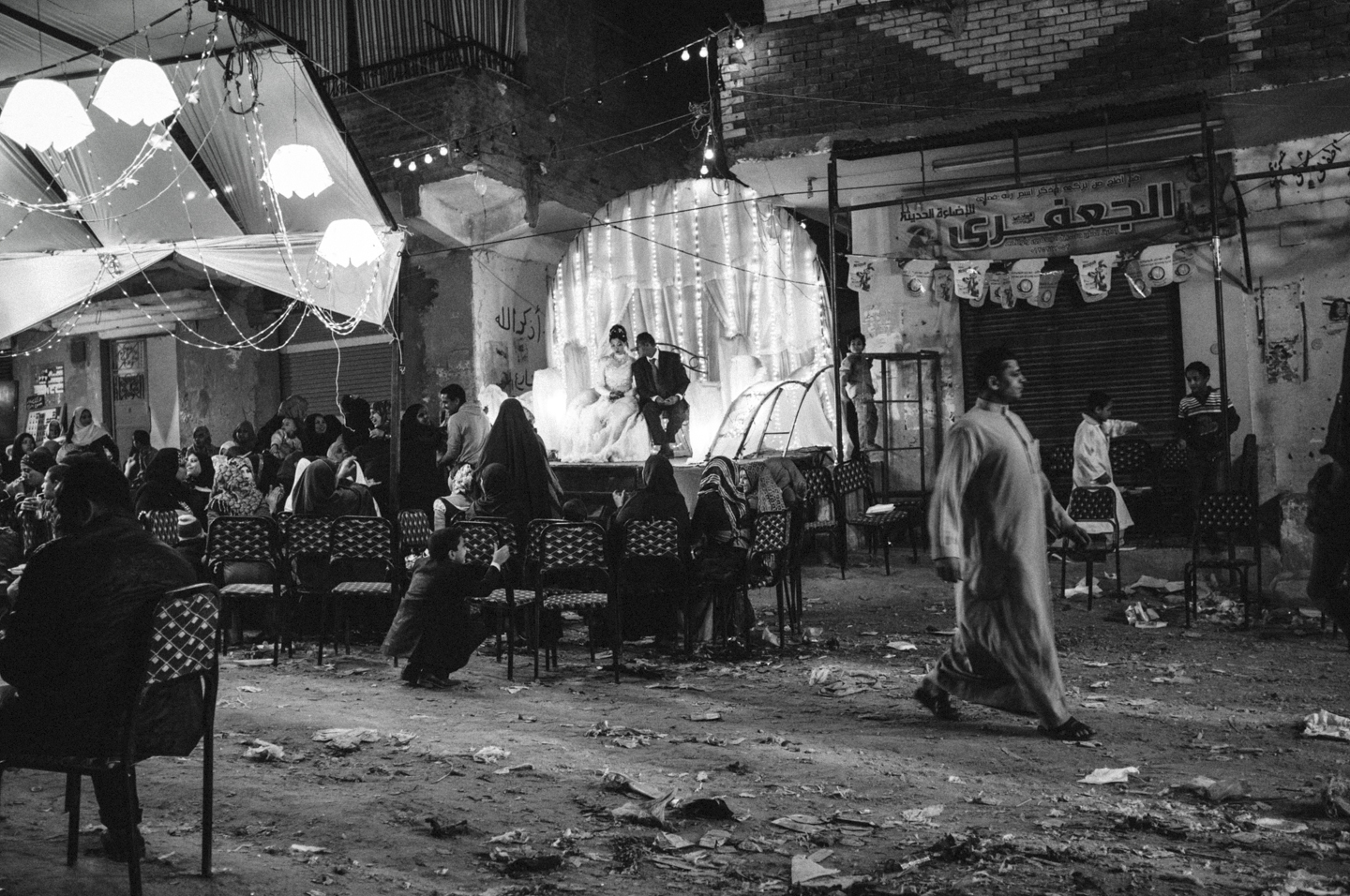

My perspective, though, was always that of an outsider. I’d only read about Tahrir Square in books, most of them coming-of-age novels by the Caulfields of Cairo. I’d never smelled tear gas, brushed shoulders with protesters at midnight, chanted slogans, and experienced the dreams and desires of a revolutionary youth fighting the good fight. There are, however, those whose passion takes them beyond the pages of books and strips of celluloid to the beating, palpitating heart of things. Emine Gözde Sevim is one of them. Of Turkish and Afghan origin, Sevim slung a camera on her shoulder and set out for Egypt to document with aching beauty the days of the Revolution, as well as its aftermath and impact on the quotidian existence of ordinary Egyptians. In a slim, yet telling volume of photographs, she makes no statements, passes no judgments, and draws no conclusions; she simply, like the bards of her ancestral homelands did, and still do, tells a story – and a very compelling one to boot.

A young, yet highly-accomplished photographer who has showcased her works in formidable galleries and worked alongside some of the industry’s greats, Sevim’s Embed in Egypt – her first book – chronicles her various trips to Cairo, serving as a pictorial record of defining moments in modern Egyptian history, as well as work of art in its own right.

You describe your book as portraying the ‘emotional residue’ of life in post-Mubarak Egypt. Could you elaborate a bit on this?

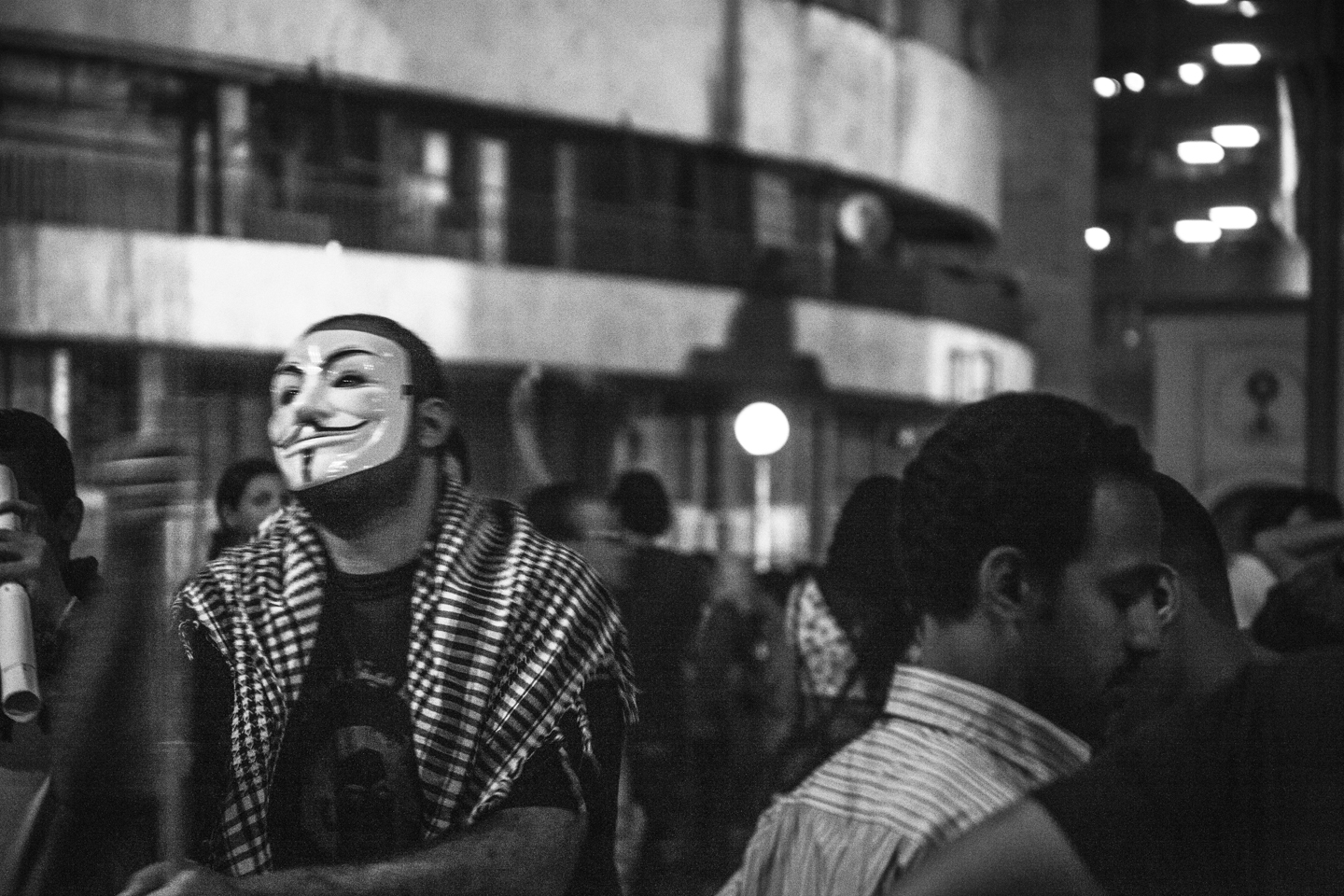

Though I was following the developments in Egypt very keenly, my actual physical experience began with my first trip there in November 2011. The period between the January 25th Revolution and the parliamentary elections earlier in November actually saw a lot of human rights abuses, military trials for civilians, and the Maspero Massacre, to name a few. Knowing about these events is one thing – one can read the facts; but what really felt personal to me was the toll all these took on individual lives.

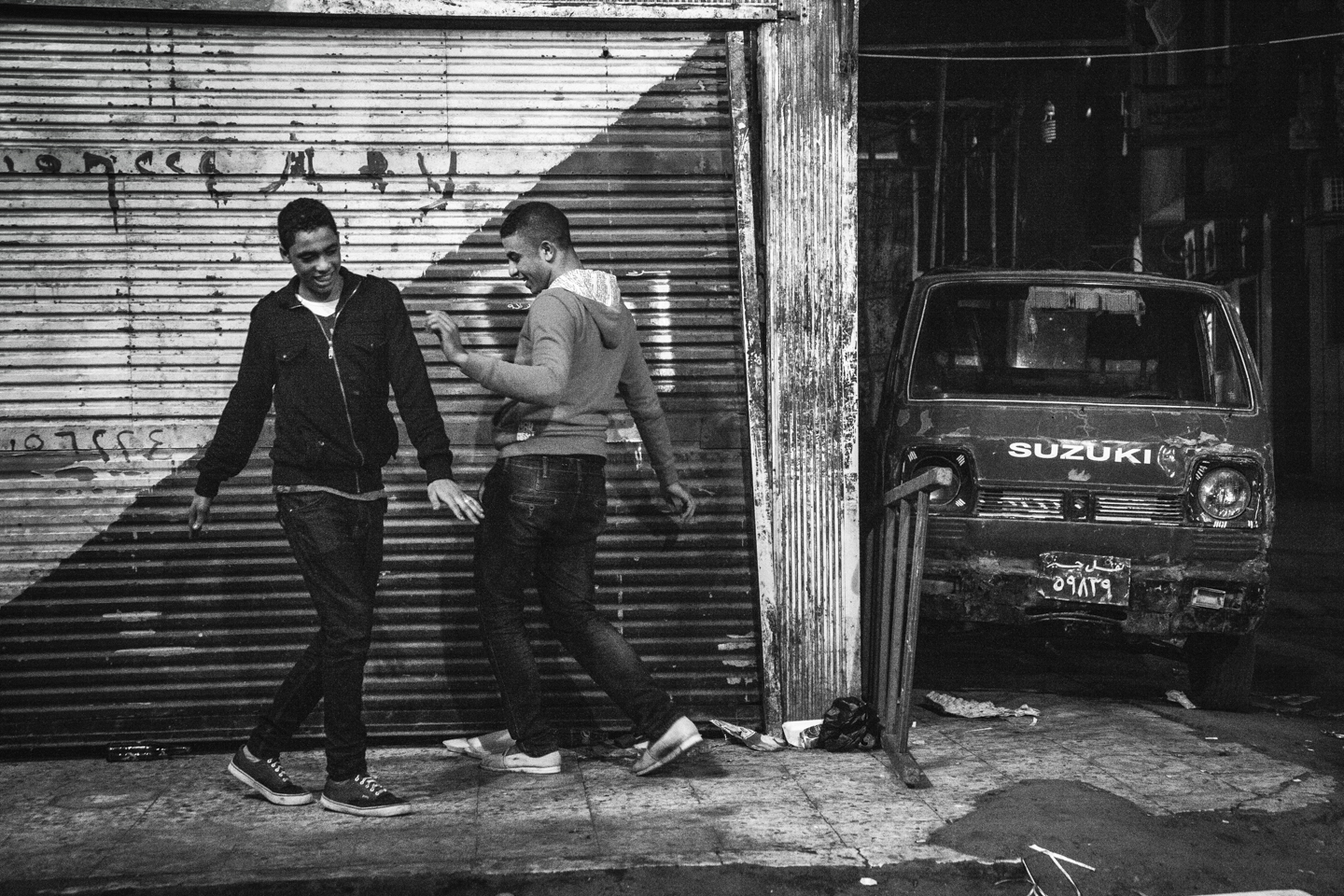

Once I got to Egypt, I became interested in particular issues and places. I wasn’t there to take pictures for a pre-meditated project; I wanted to live in that period there, and see beyond what was already seen on the news. I met a group of friends, some of whom I can say will remain among the closest I’ve ever made. For me, the experience of that period was beyond the conjoined terms we began hearing in the media, like ‘Arab Spring’. The experience of being young and living in history – which feels at times like it consumes an individual – is a transforming experience. In between, still young, we fall in love, we laugh, we cry, we create.

This was my reality there, and the photographs I made during that time became a record of the memory. The book is the self-contained existence of that.

Aside from the political upheavals in Egypt, was there anything else that attracted you to the country? Why not, for instance, publish a book on the unrest in Turkey?

For me, each place forms a very different experience, emotionally, each having its own ‘texture’; however, history trying to find its course is their common, shared condition that was my first anchor. Although events of historic importance happened in many places at once, the places I chose came from a personal curiosity, almost a bond I felt I had and had to follow, even before getting to Egypt. I wanted to go to Egypt in the same way; I was inspired, and felt the movement of millions in the largest country in the Arab world could not be overlooked. Now, it’s Turkey, because I am from there, and the country is going through historic times that I feel I must experience.

It’s not the political upheavals, but rather their historic significance and my personal curiosity and relationship to them that makes me go to some place. That is why, while I was trying to find my way to get to Egypt until November 2011, and the world had moved on to Libya and Syria by then, I didn’t; I couldn’t. Coincidentally, I shifted to Turkey, where I was born, in the aftermath of my last trip to Egypt for personal reasons, only to find myself in the middle of yet another historic shift that peaked with the Gezi Park protests. This resulted in the body of work that I’m actually currently making – Homeland Delirium – which I hope to turn into a book.

Where do you think your book sits vis-à-vis other artistic output produced regarding the Revolution (e.g. Jehane Noujaim’s The Square, Don Stone’s Walls of Freedom: Street Art of the Egyptian Revolution, Mona Prince’s Revolution is My Name, etc.)? What message(s) is it trying to convey?

Embed in Egypt is an individual’s wandering through the experience of a historic time; there are no answers, no beginnings, no real ‘conclusions’ (in fact, the full title of the work is Embed in Egypt: A Story Without a Beginning). I can’t, and am not trying to explain the Egyptian Revolution; I think such an event would require volumes. Rather, through a non-linear narrative structure, I channelled the complexity of life during that time through my viewfinder.

… The Revolution is one melody, always playing in the background, while other melodies of life come in and fade out. The guiding voice is very dimmed; there are only a few pieces of writing to ‘steer’ the experience, but never to explain

Rather than showing a very in-depth investigation of the January 25th Revolution as an event from very particular angles (e.g. those of protesters, of a woman in Egypt during those 18 days, or the graffiti that transformed the physical landscape of downtown Cairo), Embed in Egypt is different: it doesn’t have chapters or a specific focus on the Revolution, even though it contains these details. If we were to think of it like a song, the Revolution is one melody, always playing in the background, while other melodies of life come in and fade out. The guiding voice is very dimmed; there are only a few pieces of writing to ‘steer’ the experience, but never to explain.

What was living in Egypt like between 2011 and 2013? What sorts of things did you witness there?

I began going to Egypt every two months, and then spent six months straight there, so I wasn’t there the whole time between 2011 and 2013. However, this segmented experience actually made the changes all the more apparent, in a way. There are too many changes to list here, but it should be mentioned that the events the general public reads about in the news never happen overnight. For instance, during a protest in October 2012, buses of Muslim Brotherhood supporters were torched, and for the first time, civilian groups (Muslim Brotherhood supporters and their adversaries) clashed. This was very worrisome and poignant in terms of the level of societal discontent and the instability at the time. Of course, this dynamic landscape also affected the individual experience, and my work was also affected by these changes. Originally, I was taken by the movement and colour in the streets upon my arrival. However, during my second trip, life became more still, and the connection I felt was of a memory of a certain time that was passing all too fast. Accordingly, I felt black-and-white photographs were more suited to mark this experience.

In your opinion, would you say Egyptians are better off now than they were before the Revolution or during Morsi’s presidency (i.e. pre vs. post-Sisi)? What do you make of things there at the moment?

I haven’t been back to Egypt since March 2013. However, I believe if we think of things not in terms of political figures, but actual conditions on the ground based on universal principles, perhaps we could tackle the issues. Or, even more specifically, we could ask if the original demands of the Revolution – ‘bread, freedom, dignity’ – have been fulfilled. These demands, for decades, have not been fulfilled. It will take years of work, but unfortunately thus far, I believe we are nowhere near.

Of all the images you took during your stay in Egypt, which ones do you find the most poignant, and why?

It is very difficult for me to think in this way. However, the photograph of the concrete blocks in the formation of a wall with a mural on it is one of the most symbolic for me. I took this photo in 2012. The wall was on one of the several streets that lead to Tahrir Square, which were blocked at that time. The wall and the mural are so symbolic of the situation: on one hand, concrete blocks prevented access to the Square – of Freedom, as it was once called, by many; on the other, however, its surface became a canvas, and of all things what was painted on it was the continuation of the road. The mural is hopeful, but also realistic: if you look closer, you’ll notice security waiting at the end of the road. It is so simple, yet so telling. That’s life.

Will any of the photographs be exhibited anywhere?

The photographs were previously exhibited in Istanbul on a small scale, and I am currently working on exhibition possibilities – both group and solo – for the near future. Everything is being discussed, so I’ll need to update you as things become confirmed.

What do you envision for the near future of Egypt and Egyptians? Can we be hopeful?

Although since the end of 2010, we have been seeing progressive violence in the region, this cannot undo the fact that the original movements began as truly hopeful. For all the unfinished histories in the region, the situation has become very complicated, especially with the most recent developments. Having been in the middle of that time in history, it’s more difficult than ever to tell what will come next. Unfortunately, it takes only a few powerful people to make barbaric decisions and cause chaos. So, for the near future – not just for Egypt, but also the region as a whole – I am concerned about what will come. But if hopes for a better society have the potential to survive during these tumultuous times, and as long as the potential is alive, one cannot give up.

‘Embed in Egypt’ can be ordered from Emine’s website.