‘My work is so pure that it appeals to the children of the Revolution themselves’

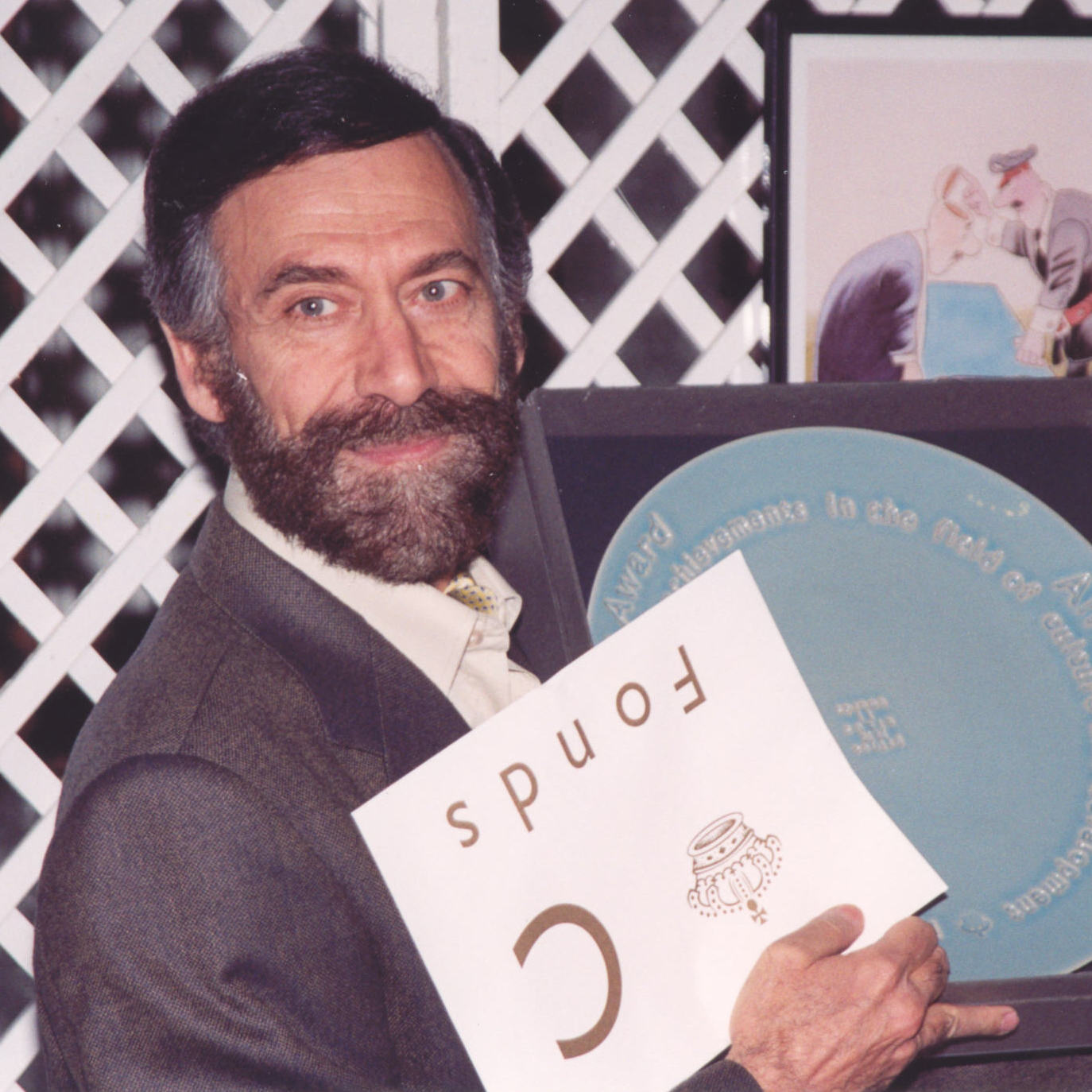

Ali Ferzat is a renowned Syrian political caricaturist and activist. In 2011, he was awarded the Sakharov Prize for peace, and was listed as one of Time magazine’s 100 most influential people in the world in 2012. Two years ago, during the beginning of the insurgency in Syria, Ferzat was attacked, his hands were broken, and he was left for dead on the side of the road – such is the controversy surrounding his caricatures. A few of Ferzat’s works were included in the recent #withoutwords exhibition of Syrian artists at the P21 gallery in London this summer, at which I got the chance to speak with Ferzat about his caricatures, among other things.

Just to begin – could you tell me a bit more about how you managed to publish your drawings during the Assad regime? How did you evade censorship?

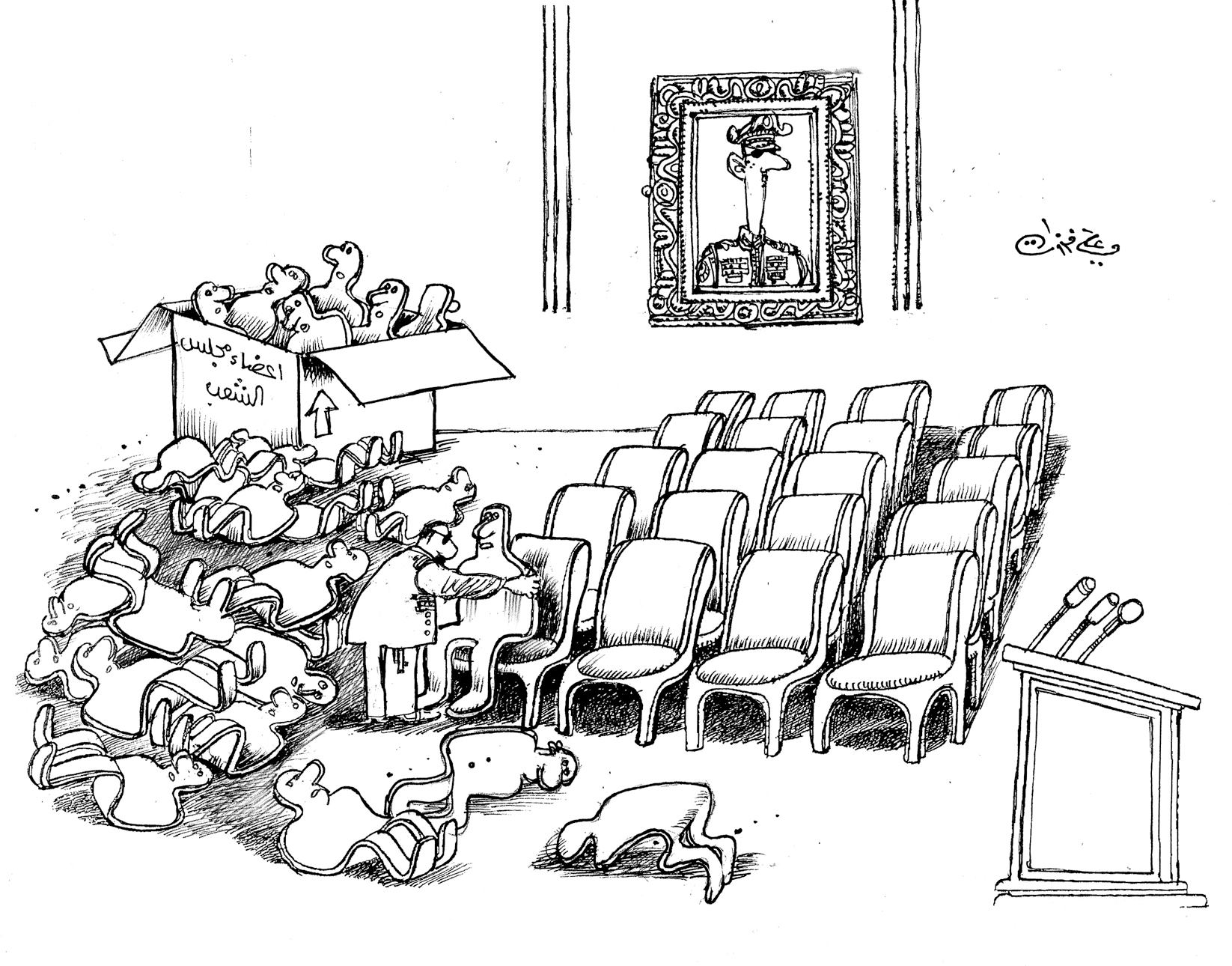

I dealt with the regime as though I was dealing with a venomous cobra. I had to attack them from a place where they couldn’t see me; so, I tackled issues that could have applied to them, but they could not say for certain that [the drawings were] definitely about them.

Yes, because you said they were about foreign political issues rather than Syrian ones …

Yes. For example, I would say that the drawings were dealing with the political situation in Iraq, or other countries; so, we were technically talking about Iraq, but of course, [the drawings] could have also applied to Syria.

Do you think that, as well as having avoided censorship, their non-specificity shows that the situations you depict are actually somewhat universal?

Yes. In the beginning, I didn’t personalise the cartoons; I kept them vague, and very general, so that they would apply to any country around the world – and that’s a very good point, because in fact, these cartoons have spread internationally. They don’t need a language – they’re just images without any words. I raised the issue of Syrian politics to the whole world so that they [could] understand what’s happening inside by just looking at these cartoons.

Then, I moved onto the next stage – breaking the ‘wall of fear’ – when I felt it was the right time. I felt that people had been waiting for this. Then, of course, the revolution started, so I began tackling the regime, the president, and the secret service directly, showing them as distinct [entities] with their own faces and personalities. This attack on the Baath (socialist) party, or, in fact, any Syrian party, had never happened in the years since the regime [came to] power in 1963. It was like a victory for liberation; it broke the ‘wall of fear’, and the revolution started three months afterwards.

I’m also interested in the way in which social media has played such a huge role in the Syrian revolution, in creating new ways of visualising and representing conflict. How do you view the role of social media in the revolution?

Social media gives you a lot of help, in a way, but in another way, it’s not going to enable you to address the main issues; it’s still firmly in the arena of personal opinion, and it won’t necessarily give you proper, objective information. You can’t get the facts of the revolution just from social media – you really only get opinions, and you have to really search for which opinion is ‘better’ or more true to the reality. But, generally speaking, it gives a truthful account of what’s happening.

Considering photography – for example, the work of the collective Lens Young – do you think that it’s empowering for civilian artists in Syria to be able to present these images to the international media in new ways?

These images might be manipulated as well – they give an idea of what’s happening, but might give the wrong information as well. The good thing about social media, however, is that you’re not waiting around for CNN or any of the other big media outlets to give you the news from the ground. There are a lot of people who are effectively correspondents on the front line, and [they] can give you, for example, the same photo from different angles. In this case, because there are so many different perspectives of the same image, they are unlikely to be misleading when considered collectively.

I found it really interesting how you’ve spoken about the role graffiti has played in this revolution – particularly considering the fact that the revolution started with graffiti*. Graffiti continues to play a huge role in the movement – what do you think it is about both street art and caricature that speaks so directly to the movement?

The unique thing about street art and graffiti in this revolution is that it has allowed all of the people from Syria to engage with the movement, and [they are] platforms for the creativity of people from different background and different ages. It is the same for cartoons, music, and singing; it is because all of these art forms are non-political from the start.

They’re not political, did you say?

Well, yes, in a way, because this is a movement of regular people who just want to stop this regime from committing the barbarian acts that they’ve been carrying out over the past 50 years. It’s not about a political party that wants to displace another party; in a way, the work is political, but in a different sense. Although it’s about politics, the people on the ground don’t listen to the political rhetoric.

When we started the uprising three years ago, there wasn’t an opposition anywhere – it didn’t exist. The art is not directly related to the opposition. The opposition is still outside – it is trying to do something – but the real people on the ground, the civilians and artists who started this movement and are pushing it forward perhaps don’t even have TVs to see what’s going on with the opposition, so they don’t care … the people are leading the movement, and the opposition party is following them.

Do you think that caricature as a form is inherently subversive?

Yes, in a way, because it allows people to claim their rights, and to be openly and actively against a certain problem. In this way, it gives people a sense of freedom.

How do you think it’s liberating vis-à-vis other forms of art?

Caricature is on the front line against dictatorship. It is an art form for all people – people who may not necessarily understand painting or sculpture, but [who will all] understand caricature. Also, it’s daily, and so it gives the audience a daily view and keeps them up-to-date.

You have said before that you don’t believe art and politics can mix, and we have touched on this briefly already, but I was wondering what your opinion is on this … because this exhibition seems almost entirely based on the mix of art and politics, and art based on politics.

Yes, but the thing is, as a person, I will tackle political issues – but at the end of the day, I am not a politician. But as an artist, you still need to highlight these issues.

Caricature is on the front line against dictatorship. It is an art form for all people – people who may not necessarily understand painting or sculpture, but [who will all] understand caricature

I see, so as an artist you need to tackle important issues but not engage in political polemics yourself …

Yes, exactly.

And your criticism of Adonis [the well-known Syrian poet]?

Yes – I criticised Adonis because he engaged politically, and placed himself firmly on the side of the government. He himself criticised the revolution, and the people themselves. He can criticise me personally as Ali Ferzat, he can criticise individual people, but he really cannot criticise the majority or the movement. He also contradicts himself; he supported the [1979] revolution in Iran, which was all about religion, but now he’s outspoken against the Syrian revolution, because he says it’s coming from the mosques. So you can see the contradiction. This regime came riding in military tanks – but he hasn’t criticised the regime, he’s criticised the people whose crime was simply asking for their freedom.

You’ve said before that this is a ‘revolution of children’ – this is a poignant description, especially when looking at the photographs coming out Syria at the moment. Downstairs, in the room dedicated to photographs taken by Lens Young, there is a sign stating that nobody under the age of 18 can enter, but there are very young children in almost every single photograph. Children have indeed played a huge part in this movement, and of course, it was the plight of children in Daraa that sparked the revolution. Similarly, I feel like the cartoon format is inherently more accessible to children.

I address ideas, but in a way that everyone can understand. Children are drawn to the cartoons because there is still hope in them – [they] don’t just depict the issues in a depressing way in order to make people feel down. There is hope and humour there too, and that’s the good thing about cartoons. Actually, when I exhibited in Damascus, most of my audiences were children; they would come and greet me, and say hello. A lot of children are fond of my work.

That’s lovely, and so apt, considering what you were saying about this being a revolution of children.

That’s why my work is not exactly directly related to politics; it addresses political issues, but it’s more pure than that. It’s so pure [that] it appeals to the children of the revolution themselves.

Of course - because children don’t speak politics.

* The revolution was sparked in the southern city of Daraa in 2011, when at least fifteen children were arrested and tortured for painting anti-government graffiti on the walls. Amongst other reactions from the government, the children’s families were informed that they should consider their children dead, but that soldiers would come over and ‘give their wives new children’.