Slavs and Tatars on bringing the art of Central Asia and the Caucasus to Art Dubai

Initiated in 2011, Art Dubai’s Marker series highlights art from around the world, with a focus on a particular region each year. This year, the fair - which runs between the 19th and 22nd of March - has turned its attention towards the Caucasus and Central Asia, and will see the 2014 edition of Marker curated by the artist collective Slavs and Tatars. Featuring exhibitions, talks, and commissioned projects, among other initiatives, the collective will introduce five art institutions from Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Georgia, Russia, and Azerbaijan. To find out more about what they’ve got planned for this year’s edition, I talked with one of their members (who insisted on remaining anonymous) about their selections, the contemporary art of Central Asia and the Caucasus, and the allure of a land ‘east of the former Berlin Wall and west of the Great Wall of China’ …

What galleries and art institutions have you lined up for this edition’s Marker? Why do you think Art Dubai has decided to focus on Central Asia and the Caucasus this year, and what interest do you think such diverse regions will hold for audiences of a largely Middle Eastern art fair?

These regions and the Persian Gulf region share a relatively recent history of nation building – the 1960s and 70s for much of the Gulf, and the early 1990s for the former Soviet sphere; but perhaps, most importantly, the Middle East has a compelling imperative to consider the role of these regions in the development of a pluralist – even modernist – Islam. It can be argued that the ‘Golden Age’ of Islam happened not in the birthplace of the religion or only in Baghdad or Cairo, but equally in Bukhara, Khwarezm, and Samarkand, where [the contributions of Persian polymaths such as] Ibn Sina’s Canon of Medicine, Al-Biruni’s astronomy, and Al-Khwarazmi’s algebra appeared; or, in Tashkent, and even Tbilisi, where the moderate modernists such as the Jadidists inaugurated crucial reforms in educational policy.

Are there any themes in particular the works chosen will revolve around? As well, have any works been specially commissioned for the fair?

The works will indulge a notion of complexity in how one defines oneself – be it nationally, ethnically, intellectually, or spiritually. Sergei Maslov’s Dream paintings address a sense of self as topographically informed as [it is] narratively fabricated, [and] Taus Makhacheva’s Paysage defines landscape through the unlikely physiognomic imprimatur of noses.

Gulnara Kasmalieva & Muratbek Djumaliev - Untitled (ArtEast, Bishkek)

In addition to the art on display, what talks and forums will you be holding? In what ways do you plan on engaging audiences at the fair with two regions so often misrepresented and overlooked?

Masha Kirasirova, a professor at NYU’s Abu Dhabi [campus] will be looking at the curious case of Russian/Soviet Orientalism. A corrective – or counterpoint – to the perceived understanding of [Edward] Said’s Orientalism, the Russian/Soviet colonial context, unlike [that of] the British or French did not [deal with] far-off lands, but rather a proximity with historical neighbours (e.g. in Central Asia and the Caucasus), local (Tajik, Uzbek, etc.) ethnographers, linguists, [and] archaeologists … not to mention [the fact that] Bolshevism had to at least pay lip service to anti-colonial or anti-imperialist rhetoric and ideology, if not practice. As the famed ‘window onto the West’, the strength of Oriental Studies in St. Petersburg can be seen as the obverse or the underbelly of Russia’s self-identity, from its perennial debate between Slavophiles and Zapadniks to its self-colonisation.

In the past couple of years, artists as well as art institutions from the Caucasus and Central Asia have been making names for themselves not only at home and in the surrounding region (e.g. the Middle East), but also in Europe and North America. Can you tell us a bit of some of the recent (and noteworthy) artistic happenings and developments in these regions? As well, what do you envision for the trajectory of contemporary Caucasian and Central Asian art in the near future?

In Central Asia, after the fall of the Soviet Union, NGO-funded initiatives such as Soros or Hivos stepped in to support cultural initiatives. Today, after two decades, they are pulling out, with the understanding that resource-rich countries such as Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan could and should support their own cultural programmes. Unfortunately, no Central Asian country has drafted a coherent, consistent cultural policy beyond the instrumentalisation of art in nation-building exercises. The Caucasus presents a far more varied landscape given the proximities [of the countries therein] to each other, and to Eastern Europe, of these rather densely populated republics in a relatively small area. The viability of grass roots organisations in Georgia (such as GeoAir) or others is a testament to this.

Reza Hezare - Nostalgya (Yarat, Baku)

When we think of think of [the Caucasus], we often consider the three independent republics – Armenia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan. We’re thrilled to include in [this year’s] Marker the National Centre of Contemporary Art in Vladikavkaz in the Northern Caucasus, which belongs to the Russian Federation, and [which] has implemented an ambitious programme over the past couple [of] years.

If we are to believe, or even take at face value the nonsense that too often passes as wisdom today – that Islam and the West are on a collision course, that the rise of the East is a threat to liberal Western democracy – then it makes sense to look at a region equally [from a] geopolitical and imaginative [perspective], where the contrary has been the case for several centuries …

Despite the generous support of NGOs mentioned [in the case of] Central Asia, in retrospect, too little thought was given to the necessity for educational programmes, art schools, etc. to provide a long-term platform for [the] reflection, consideration, and training of the next generation of artists. [The Caucasus and Central Asia] share an urgency of art-historical continuity, one [wherein] the knowledge and experience of a previous generation can be recognised and well leveraged for the next [one], especially given the historical and political ruptures of the past century.

Aside from Marker, what else are you looking forward to at this year’s Art Dubai? Any ‘must-sees’ on your list?

The people we’ve met at the Global Art Forum, from UN policy thinkers to writers, dentists to artists, are a testament to the discursive energy that can result directly or indirectly from an [art] fair. Shumon Basar, the commissioner of the Forum put it best [when he said] ‘art as a topic isn’t privileged over other topics. I think that’s healthy’.

A still from Taus Makhacheva’s Bullet (North Caucasus Branch of the National Centre for Contemporary Arts, Vladikavkaz)

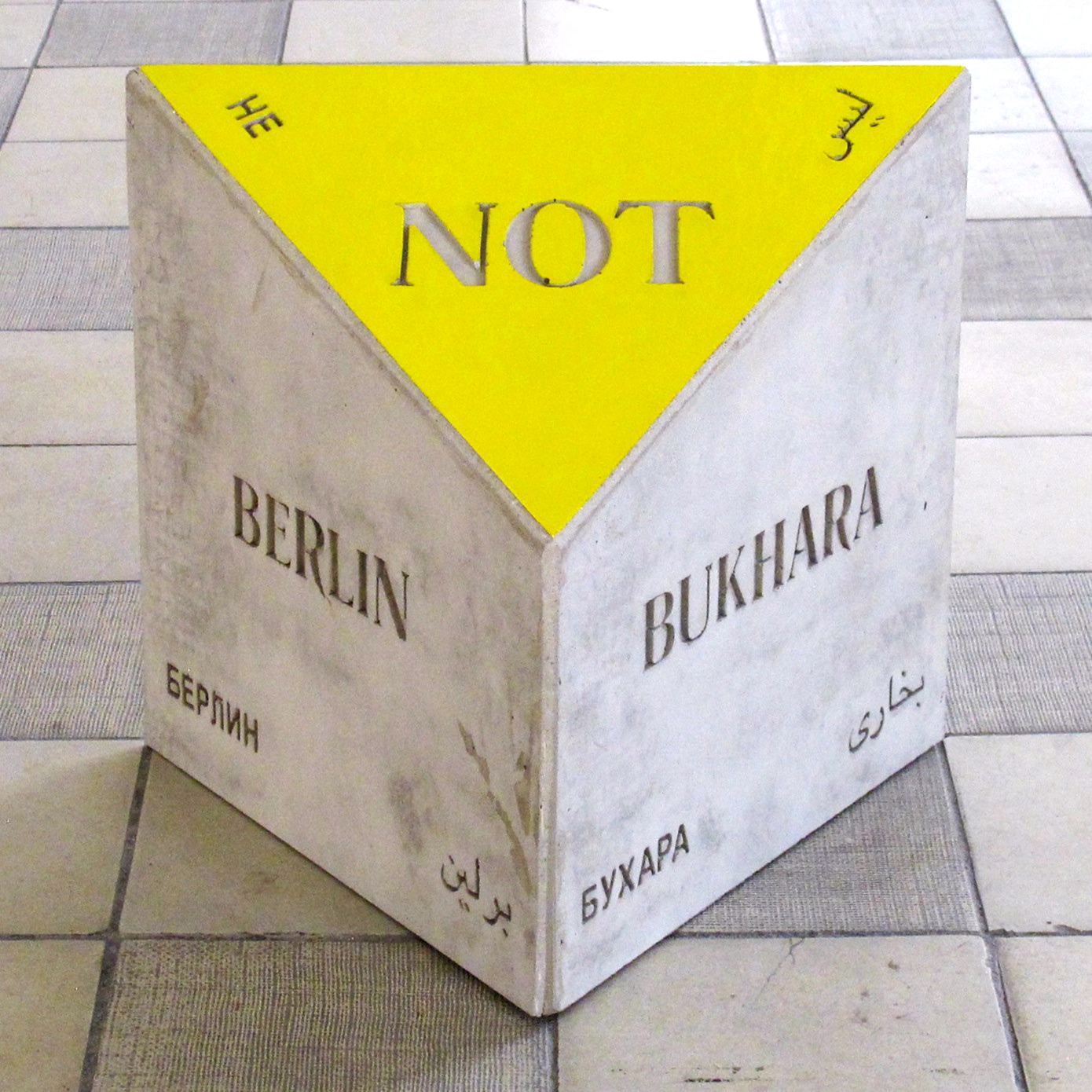

Lastly, what is it exactly about the area ‘east of the former Berlin Wall and west of the Great Wall of China’ that has, and that continues to inspire you?

If we are to believe, or even take at face value the nonsense that too often passes as wisdom today – that Islam and the West are on a collision course, that the rise of the East is a threat to liberal Western democracy – then it makes sense to look at a region equally [from a] geopolitical and imaginative [perspective], where the contrary has been the case for several centuries, from the transnational cosmopolitanism of Tbilisi to the [case of] the Jews of Bukhara.

Geographies are as political as they are poetic, [and as] real as [they are] imaginary. We founded Slavs and Tatars in 2006 for equally intellectual and intimate reasons. Of course, we are interested in researching an area of the world – Eurasia – that we consider relevant, politically, culturally, and spiritually. We take issue with various ideas: the positivism that seems to be so rampant in the West, the idolisation of youth coupled with the dismissal of age; an excessive emphasis on the rational at the expense of the mystical; the segregation of children from adults at social functions; splitting dinner bills, and [the] disproportionate attention [given] to the individual over the collective …