Ara Güler’s photos of Anatolia raise questions about Turkish identity and culture

Photographs courtesy the Freer Gallery and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives

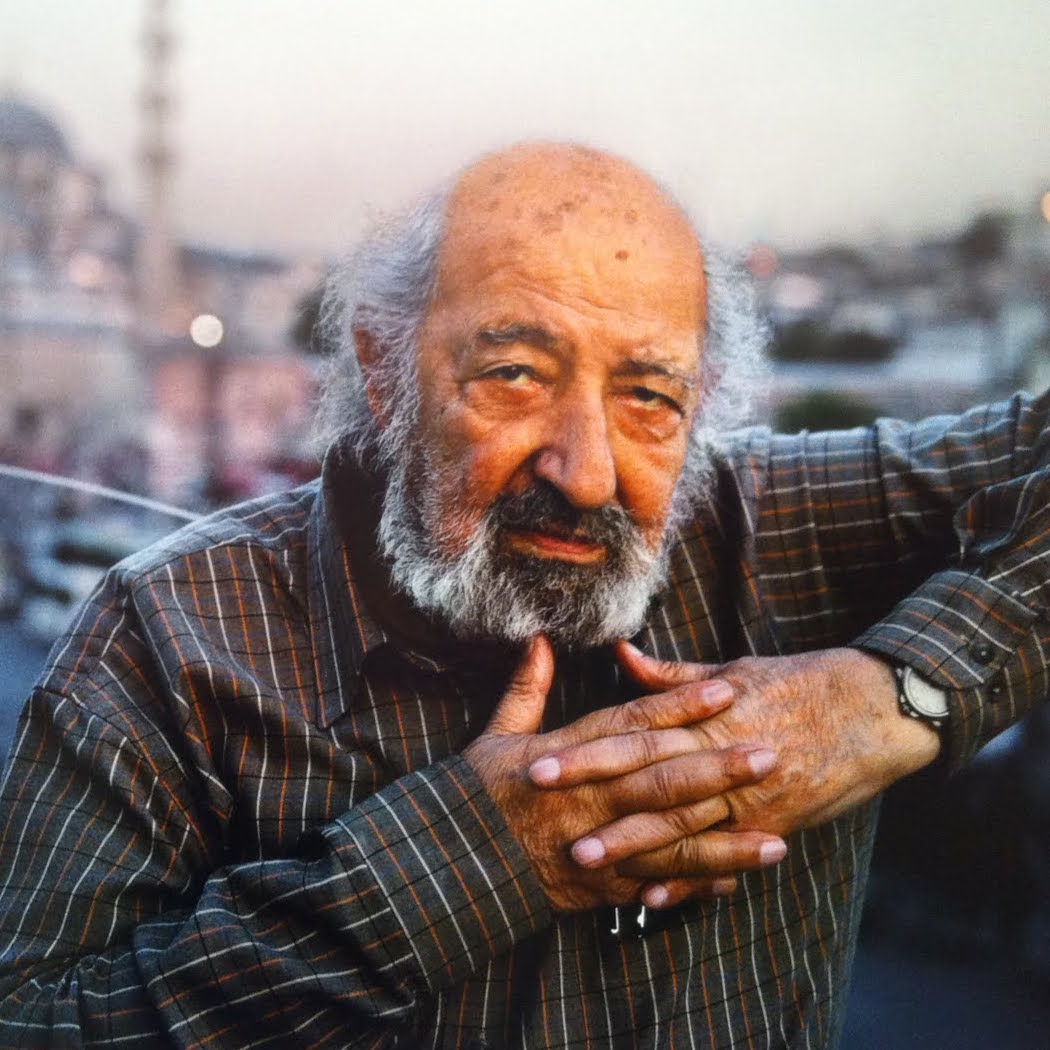

Known as the ‘Eye of Istanbul’, Ara Güler may be best known outside his native Turkey for the iconic images featured in Orhan Pamuk’s memoir, Istanbul: Memories and the City, which beautifully illustrate the notion of hüzün (a sort of nostalgic longing) so prevalent throughout the book. Güler does not consider himself an artist, but rather a photojournalist - a distinction he believes is rooted in the importance of observation. Accordingly, an exhibition of his photographs at Washington, D.C.’s Freer and Sackler Galleries of Asian Art featuring 21 black and white silver gelatine prints taken in 1965 asks viewers to consider Güler’s distinction between observation and art, challenging his assertion that photographers capture truth, while artists create works of fiction. More interestingly, however, a close examination of the photographs of Armenian and Seljuk ruins from Anatolia preserved in the gallery’s archives reveals a complex historical narrative of the country.

The exhibition, co-curated by Freer and Sackler’s Nancy Micklewright and students from John Hopkins University comprises a collection of Güler’s photographs donated to the Smithsonian by Raymond Hare, a former US ambassador to Turkey. According to Micklewright, the goal of the exhibition is to complicate Güler’s belief in a dichotomy between art and observation. The curators encourage audiences to approach the exhibition from a perspective of ‘visual literacy’, to ‘look at the images carefully and think about the photographer’s choices’. Throughout the exhibition, Micklewright and the students aim to explore the role of photographs in an art museum context; that is, to think about and consider how, by displaying photographs in art museums instead of in newspapers or history museums, the context of an art museum can blur the art/observation distinction. Güler’s eye for light, and for capturing the juxtapositions between the historical and the modern enable him to explore issues of identity and memory in a country where the past is constantly being reinterpreted.

Ara Güler’s Anatolia divides Güler’s images into four categories, each matched with an explanatory quote from the photographer. The first category, Eye of the World highlights Güler’s ability to capture unique moments, while the second, Magic, addresses his relationship with time, both in capturing specific moments on film, and in documenting the impact of time on the Turkish landscape. In many ways an expansion on the themes explored in Magic, the third category, Change – which Micklewright characterises as an attempt to capture ‘vanishing ways of life’ –is full of images depicting decaying monuments from the past that serve as reminders of Anatolia’s lush history. The final category, Truth, demonstrates Güler’s approach to documentation, particularly his shooting of objects from multiple perspectives in order to preserve their ‘true’ form.

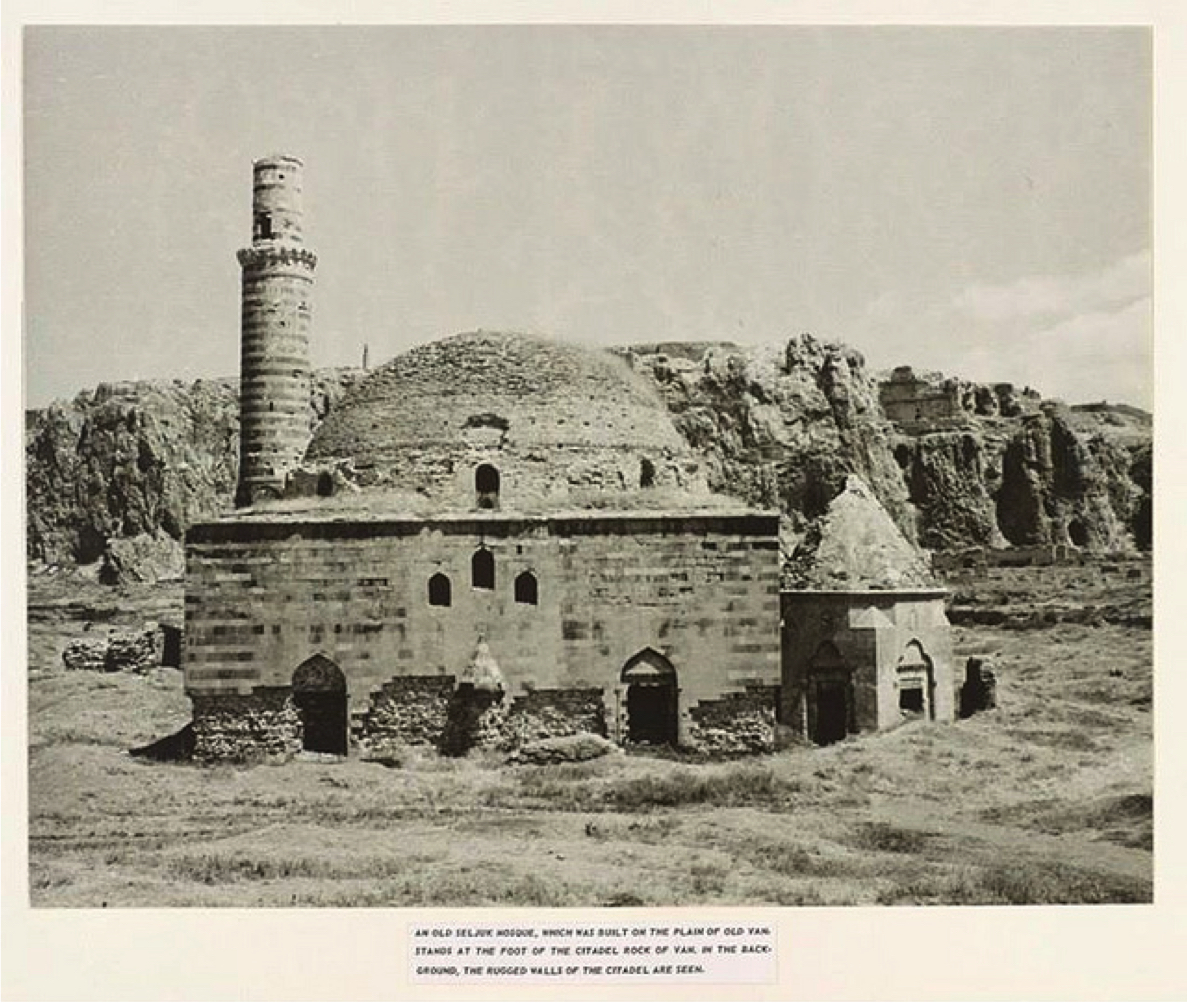

The Köse Hüsrev Paşa Camii in Van

The curators have carefully highlighted elements from Güler’s photos to challenge the assumed dichotomy between observation and art. Micklewright also told me that while planning the exhibition, she and her team paid special attention to the role of archives in a museum context, a fact not necessarily evident to casual viewers. While the debate over art and observation is an interesting ‘lens’ through which to view Güler’s photographs, exploring the role of memory in the exhibition leads to the contemplation of deeper issues of ownership and identity. Archives are repositories of memory, as Michel-Rolph Trouillot argues in his groundbreaking work on historiography, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. Our conceptions of the past, of our place in the world, and of the identities we construct for others and ourselves are dependent on archives, both formal and informal, while photographs and other artefacts preserved in the hallowed archives of museums – including art museums – can alter the way people view history. Moreover, existing power structures determine what enters these archives and what remains ‘silenced’ outside the dominant narratives of history.

Though perhaps best known for his iconic images of Istanbul, there are none on display among the 21 images in the gallery; Güler believes his most important work is the documentation of historical ruins throughout Turkey. He has photographed the Hittite site, Nemrut Dağ, the so-called ‘Noah’s Ark’ near Mount Ararat, and the small town of Geyre, the photos of the latter having led to the discovery of the Hellenistic city of Aphrodisias. The monumental architecture on display in the photographs is that of Eastern Anatolia – remnants of Armenian and Seljuk cultures, some almost forgotten, and some which have been interpreted to frame current identity struggles in Turkey. Identifying as a Turk of Armenian descent, as Güler does, is contested in modern Turkey, where conceptions of ‘Turkishness’ challenge the very existence of a hyphenated ‘Turkish-Armenian’.

The Church of St. Gregory of Tigran Honents in Ani

In the West, the AKP (Justice and Development Party/Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi), the current ruling party in Turkey, is often cited as a paragon of Islamic democracy, though this notion has been challenged recently by popular anti-state protests and the rise of what some view as anti-democratic elements in the republic. Under AKP rule, there has been a resurgence of interest in Ottoman and Seljuk history, and the appropriation of the past of previous Muslim empires has led to a new identity rooted in empire and Islam. Güler’s photographs, however, predate this new narrative, and his focus on Armenian and Seljuk monuments complicates it by revealing past perceptions of Turkish history - a history now dominant yet formerly marginalised.

An exploration of the state of the monuments today reveals how Turkey’s perception of its past has changed since the 60s; the Seljuk monuments have been rehabilitated and reincorporated into the dominant strain of Turkish history, while many Armenian ones are still languishing

His photographs from the 60s document the existence of non-dominant strains of the past. Out-of-favour Armenian and Seljuk history was silenced following the formation of the Turkish Republic in the 20s, and left to deteriorate in marginalised Eastern Turkey, while Greek and Roman ruins were excavated and rebuilt for consumption by tourists and Turks alike. These photographs capture the neglected and deteriorating buildings, providing evidence of this marginalisation. An exploration of the state of the monuments today reveals how Turkey’s perception of its past has changed since the 60s; the Seljuk monuments have been rehabilitated and reincorporated into the dominant strain of Turkish history, while many Armenian ones are still languishing.

Depiction of the Biblical tale of Jonah and the Whale on the South Wall Church of the Holy Cross on Akdamar Island

For example, the exhibition includes a photo of the Büyük Karatay Medrese in Konya. The Seljuks, who made Konya their capital during the 12th and 13th centuries, built the medrese with a beautifully carved monumental stone entranceway. Formerly a dusty, deteriorating provincial museum, it was in dire need of emergency restoration due to years of neglect. the Büyük Karatay Medrese has been recently refurbished – a move indicative of a general resurgence of interest in not only Seljuk monuments and ceramics and tiles, but also Turkish history in general. Guided by the vision of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founder and first president of the Turkish Republic, many Turks for years downplayed their Ottoman and Seljuk past, and instead emphasised a new and ‘modern’ national identity forged after the First World War, the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, and the formation of modern-day Turkey in the early 20s. Under the AKP regime, however, the tone of rigid secularism is softening, and alongside this shift, one can witness the ‘reclamation’ of the Islamic history of the Republic’s forebears.

On the other hand, however, many of the Armenian monuments photographed by Güler in the 60s are still in a state of disrepair. When I visited the ruins of the ancient Armenian city of Ani (documented in the exhibition) in 2010, my party was the only group exploring the site. Mere kilometres from the Armenian border, Ani has been neglected – and perhaps abused – by the Turkish state ever since it gained control of the region in 1921. Almost inaccessible without private transportation and subject to looting, negligence, and even target practice by the Turkish military, Ani is one of 12 sites worldwide facing ‘irreversible loss and destruction’, according to a 2010 report by the Global Heritage Fund. My own views of the site mirrored the same wild isolation and disrepair reflected in Güler’s photos, taken some 45 years before I visited Ani. Though the Turkish Ministry of Culture has begun restoration work on several of Ani’s monuments, it remains to be seen to what extent alternative narratives of history will be incorporated into its rehabilitation.

Walls in Ani

As the Ministry of Culture carries out research and restoration, and thousands of tourists pour into Ottoman, Seljuk, and Hittite sites around Turkey, many of the Armenian ones are still suffering from a lack of funds and visitors, and are becoming increasingly forgotten. The exhibition at the Smithsonian successfully addresses the problematic nature of Güler’s distinction between observation and art. In beholding these archived photographs of marginalised histories and monuments, one has the opportunity to re-examine changing narratives of Turkish history and explore issues of identity, memory, ownership, and nationalism.

‘In Focus: Ara Güler’s Anatolia’ runs through August 3, 2014 at the Smithsonian Museum’s Freer and Sackler Galleries of Asian Art in Washington, D.C.