Asad Faulwell delves into the world of the women of the Algerian War of Independence

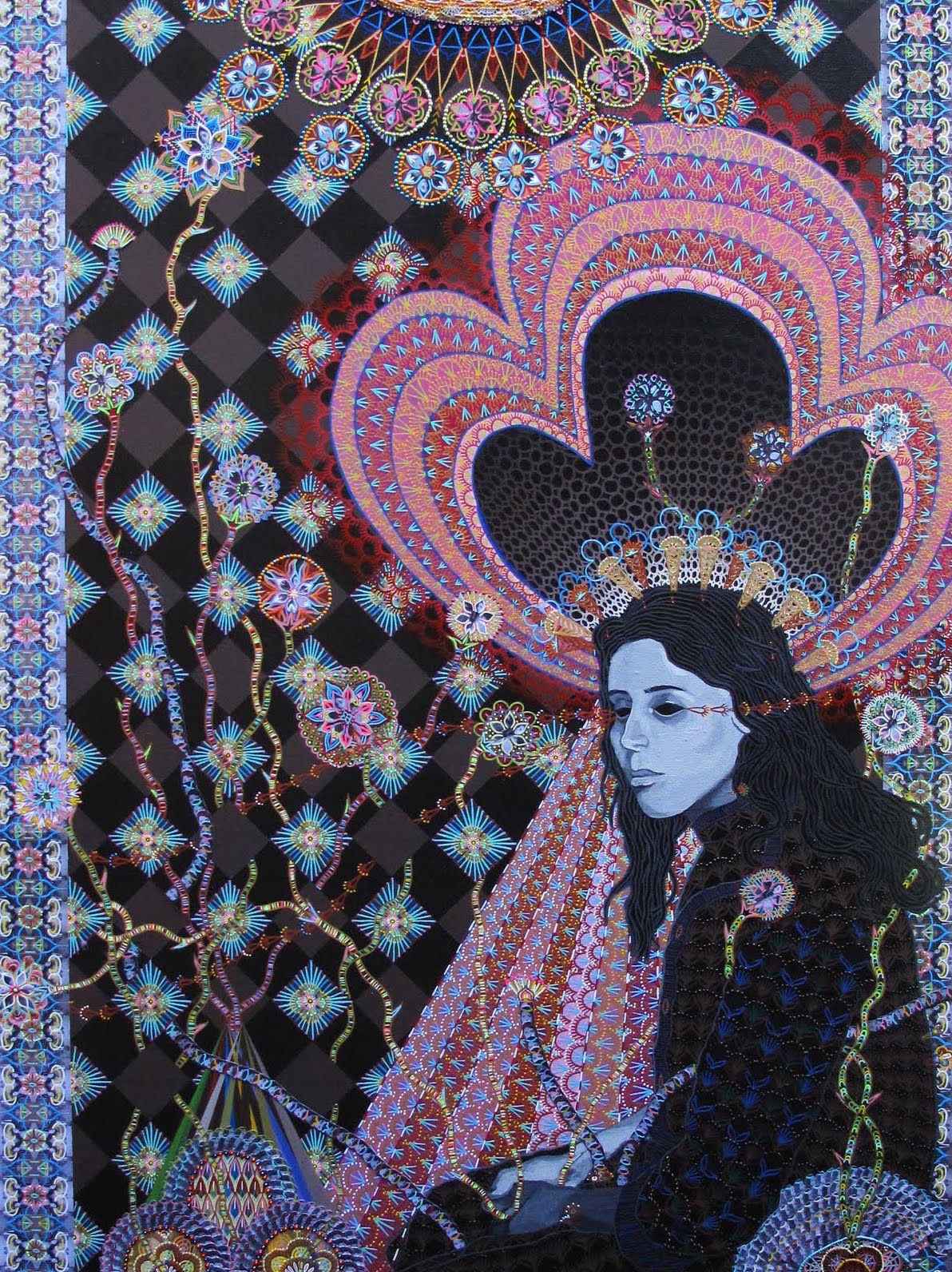

With references to works by the French Orientalist painter Eugène Delacroix and Pablo Picasso, a book by philosopher Frantz Fanon, and a song by an indie American rock duo, Bed of Broken Mirrors represents the first solo exhibition by Iranian-American artist Asad Faulwell at Dubai’s Lawrie Shabibi gallery. In his colourful, surreal, and electrically-charged portraits of women who played an active role in the Algerian War of Independence (1954 - 1962), Faulwell explores not only the stories of these all-but-forgotten ‘heroines’, but also their complexities, the suffering and agony they must have faced as participants in a bloody civil war, and what he terms the ‘moral ambiguity’ of using violence in fighting despotism.

His works still hanging in the gallery (the exhibition runs through March 11), I talked with Asad at length about his motivations and ambitions for his Les Femmes d’Alger series, revolutions old and new, and the place of his work within the spectrum of art surrounding the Algerian War of Independence.

Tell me a bit about the Les Femmes d’Alger series, which you’ve been working on for quite a while now – how did it begin, and what inspired it? As well, what does the title of the exhibition refer to?

The Les Femmes d’Alger series depicts female combatants from the Algerian War of Independence, particularly the women who took part in the Battle of Algiers. The series is intended to shed light on these women in order to both examine their lives, and to address larger issues such as the lingering effects of colonial rule, gender inequality, and the morality (or immorality) of violent resistance. The series also has [links] to art history; [the title] refers to [Eugène] Delacroix’s [1834 painting] of the same name, and also Pablo Picasso’s interpretation of that work. While those artists depicted an Orientalist and sexualised scene of anonymous women in a harem, I [on the other hand] wanted to make a contemporary version of those paintings based on specific women, [and] based on research and facts. I view Delacroix’s works as a testament to the time he lived in; they are visual documentations of the colonial mindset, [and] I wanted to upend that way of thinking.

The real catalyst for the work was [Gillo] Pontecorvo’s film, The Battle of Algiers, which I watched in 2007. That movie really planted a seed [in me] that pushed me to do two years’ worth of research into the lives of the women [of the Algerian revolution] and eventually to make works about them. The early works were more collage-based, and did not have painted figures in them; they tended to be small and largely colourless works. Over time, they changed in [terms of] scale, colour, and ambition to become what they are today.

The title of the exhibition was taken from a lyric by the [American rock group] The Mars Volta. The lyric goes: I saw you leave and crawl into a bed of broken windows. I liked the image of a bed of broken windows; it goes against everything a bed should be: a place that provides rest, safety, and comfort. I saw these women and men [who partook in the revolution] as forever searching for peace, but being unable to find it. They were either haunted by what they had seen, what they had done, or what had been done to them. I saw their lives as a bed of broken windows. I changed the song lyric tothe eventual title of the exhibition, A Bed of Broken Mirrors, because I thought of a mirror as being something that forces self-reflection.

As an Iranian-American artist, one would naturally expect you to explore subjects ‘closer to home’; why Algeria, and in particular, a specific episode in Algerian history?

In a sense, my decision not to make works about issues that are directly Iranian or American was a conscious one. The art world has this bizarre need to put people into neat and tidy boxes based on race, nationality, gender, and/or sexual orientation. When I look at other disciplines like writing, film, music, etc., I don’t see these restrictions. I don’t know a single human being who only has opinions or interests that pertain to his or her nationality or race. I decided I was going to make works about what interested me, regardless of geography or gender. Many people who have never met me or read my bio assume that I am an Algerian woman. I actually like that confusion; to me, it means that I am successfully pushing back against the art world’s undercurrent of segregation. Also, although this body of work is about Algeria, I believe it is universally relatable. [Revolution] is a story that has played out all over the globe, and that continues to repeat itself today.

Can you draw any parallels between the revolutions that occurred in Iran and Algeria during the 20th century?

I think the revolutions in Iran and Algeria were very different. In Iran, [the people] were rebelling against an Iranian ruler who was tainted by corruption, and who had used violent oppression to subdue his opponents. In Algeria, they were rebelling against a foreign occupying force that was willing to use any means of violence and suppression to maintain Algeria as a colony. The revolution in Algeria was a much longer and bloodier one, and was based on secular ideals, while in Iran, the revolution ended up morphing into a religious one. I actually see much more of a connection between the Iranian Revolution of ’79 and the Arab Spring [uprisings].

In terms of the role of women in the Algerian and Iranian revolutions, though, I see a common thread. In both cases, women played a role in the revolutions, but were pushed out of the way once the revolution succeeded. Arguably, women in both countries have also seen their rights erode rather then increase since the revolutions.

The women you’ve depicted in this series refer to particular individuals; who are they, and why did you choose to feature them among all the women who participated in Algeria’s fight for independence?

I have depicted less than 15 women in the series. The reason I have depicted such a small number compared to the thousands of women who actually took part in the war is that it is extremely difficult to find the names of all these women. The ones whose photos I [was] able to find tended to be those who carried out high-profile attacks, or who had high-profile trials in France. The photographs almost always came from either press conferences after the women were captured, images of them walking to court in France, or images of them after being released from prison. I am always looking for new names and new photos, but in general, it is very difficult to find information about these women. In the first year of research, I had found images of four women, and since then I have found images of nine more; so, it is really not a choice I have made to feature certain women over [the others], but rather [a problem of] not being able to find enough information. The names of some of the women I have been able to find information about are Djamila Bouhired, Zohra Drif, Hassiba Ben Bouali, Ourida Meddad, and Danielle Minne.

While I do see my work as a celebration of resistance, I do not see it as a justification or celebration of violent resistance. I [rather] make an attempt to show the torment and psychological anguish that these women must have lived with. If anything, I think my work points to the moral ambiguity of using violence to overthrow an oppressive entity.

Last year, artist Ahlam Shibli was criticised for presenting Palestinian oppositionists as heroes, as was filmmaker Ziad Doueiri for his depiction of a Palestinian suicide bomber and the Palestinian resistance in The Attack. Though we’re not talking about Palestine here, a comparison of sorts could possibly be made with respect to the subjects on display in Bed of Broken Mirrors; how do you view the women – and men – who fought against the French to win their independence, and the means they used to attain it? What message(s) do you wish to impart to your audiences?

I agree that there is an undeniable link to Palestine. In both present-day Palestine and in colonial Algeria, there is and was a large native population being occupied through the use of force. In both cases, these native populations are and were treated as being less human than their occupiers, and violent and non-violent resistance are and were being used to combat oppression. While I do see my work as a celebration of resistance, I do not see it as a justification or celebration of violent resistance. I [rather] make an attempt to show the torment and psychological anguish that these women must have lived with. If anything, I think my work points to the moral ambiguity of using violence to overthrow an oppressive entity. In the paintings, the women are often depicted carrying the book, The Wretched of the Earth by Frantz Fanon. In his book, he says that violent opposition to colonial rule is necessary to ‘repair’ the self-esteem of the oppressed indigenous population. I think there is a case to be made for this mode of thinking; I think there is an equally valid argument that violence in any form is never justified and is rarely effective in achieving the desired result. I really want to present information and let the viewer use that information to draw their own conclusions.

Where do you feel these pieces fall within the spectrum of art related to the Algerian revolution and Algeria’s days as a French colony? (e.g. Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers, the works of Albert Camus, Said Ould Khalifa’s Zabana!, etc.)

I love the Pontecorvo film; however, his movie was made just when the war had ended. There is a sense of hope and elation that permeates the movie despite its sad and horrific subject matter. I think he was making a great document for his time, when colonialism was ending and the non-aligned world was full of hope and optimism. I also like that Pontecorvo went out of his way to highlight the female combatants … he was sending a message about creating a free Algeria in which all of its inhabitants would be included in all aspects of society.

I see my work as having 50+ years of perspective that Pontecorvo didn’t have access to. The tension is still there, but Pontecorvo’s urgency and hopefulness is not. I would say my work actually has more of a sense of acceptance of hopelessness, which I suppose is more in line with Camus’ absurdist style. Although I can enjoy Camus’ work as literature, it will always be tainted by the fact that to the very end he was a fervent advocate of colonial rule. Reading The Stranger, I think you can see his disregard for the indigenous Algerian population; not a single Algerian speaks throughout the entire book … they only exist as props for the French characters to react to. I think Camus is a case where personal issues override intellectual and moral compass. That being said, there were plenty of French intellectuals like [Jean-Paul] Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, who played vital roles in turning French public opinion against the war.

I think that my work differs greatly from Camus’ in that I am presenting the opposite angle; however, it is similar in the sense that I am choosing to depict mostly one side of the story. My work is largely devoid of French characters; the French exist in my work – through context – although they are not explicitly depicted … Also, I see my work as a psychological examination of the women depicted in the same way that I see Camus’ work as a psychological examination of the pied noirs. That being said, [though], Camus’ work is fiction, whereas mine is based on fact, which lines up more with Pontecorvo’s film.

I have admittedly never seen Zabana! But now that you have brought it to my attention, I will make sure to check it out as soon as possible!