Six obscure tracks provide a glimpse of the ‘Golden Age’ of Morocco’s record industry

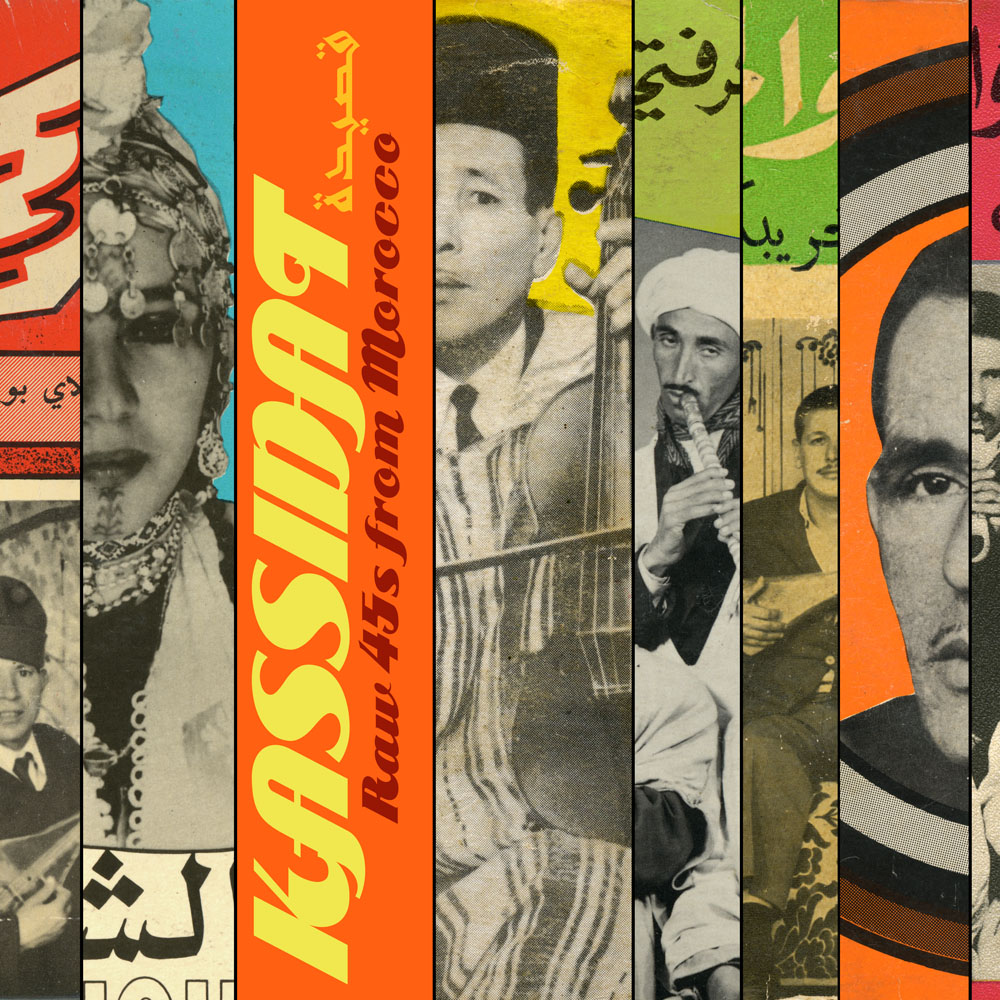

The third in a series of albums bringing together salvaged historical recordings and extensive accompanying photographs and liner notes, Kassidat: Raw Moroccan 45s by US label Dust-to-Digital presents a heady and hypnotic mix of songs from the 60s and 70s, decades referred to as belonging to the Moroccan record industry’s ‘Golden Age’. Featuring six extended tracks by popular musicians and covering a variety of musical forms and styles from the country’s various regions, it provides an appetising sample of sounds largely obscure and esoteric to Western ears.

Contributor John Wisniewski talked with the album’s producer, Dave Murray about the conception of the project, his selections, and the characteristics of the traditional Moroccan music of the era.

Could you tell us a bit about how the Raw Moroccan 45s project began?

I collect a wide variety of 78 and 45 rpm records from around the world, and I’ve always been interested in the raw and unfiltered traditional music heard on these records. In 2007, I started a blog called Haji Maji to share some of the Chinese Opera 78s I’d been collecting and learning about, since there was almost [nothing] available for English-speaking audiences. After a couple [of] years, I expanded the blog’s scope to [also] include other Asian 78s, especially [those from] Southeast Asia.

Around that time, I came into contact with the folk who run Dust-to-Digital; I’d been a fan of the label’s reissue projects ever since I’d bought their first release, Goodbye Babylon. Needless to say, I was [very] happy when they [showed interest] in my proposal for a big Southeast Asian project, Longing for the Past: The 78 rpm Era in Southeast Asia, which was released in October 2013. I knew the project would take a few years to complete, so [in the meantime] I proposed a short album of Thai Luk Thung music that had originally been released in the 60s. The idea was that it would be the first in a series [of albums] that explored a very interesting time [for] traditional records; it was a period when local companies came to dominate the record scene, as multinational labels pulled out to pursue bigger things … At the same time, the cost of recording decreased as magnetic tape became the recording medium of choice and the vinyl 45 rpm format allowed for cheap [and] quick production and distribution … Luk Thung: Classic and Obscure 78s from the Thai Countryside came out in 2008 … [which was] followed by Qat, Coffee, and Qambus: Raw 45s from Yemen, compiled and written by Chris Menist, with my designs.

Morocco had a thriving record industry that started after the country gained its independence in 1956. There were a dozen or more record companies releasing an endless stream of colourful 45 rpm records well into the 70s, when the conversion to cassette tapes resulted in a shift in the [industry]. For many years – [and this is still the case] even today, I believe – there were large quantities of leftover stock that had become obsolete when the cassette overtook the vinyl [format]; so, it’s [still] possible to find records that are essentially in ‘new’ condition. [As such], I suggested [that] the third [project] in [our] series would [focus on] Moroccan records.

On what basis did you decide to choose the songs on the album?

It was very difficult to make the selection[s], because a vinyl LP only holds about 40 minutes of music, and nearly all the Moroccan 45s are double-length, meaning that each side is about six minutes long, rather than the typical three minutes; so, I knew I could only use six tracks, [although] I have nearly 400 Moroccan records in my collection! [As a result], I set about dividing [my] collection into major [themes] and picked a couple [songs] from each one based on [factors such as] performance, sound quality, etc. Then, during the research phase, I made some cuts based on what interesting information I could [find]. In this regard, I [received] a lot of help from Ayyoub Ajmi, who along with his father runs the wonderful Moroccan music website Settat Bladi. I think we ended up with six fantastic tracks that covered the major styles of the times, [and included] a variety of instruments and regions.

What audience is such a record intended for? Is there something that translates internationally in the sound of these ‘raw’ Moroccan tracks?

I’m not really qualified to predict what other people will enjoy, since my tastes are obviously pretty esoteric; but, there is a basic rhythmic propulsion to most Moroccan songs [from the era] that should appeal to lovers of rock and roll, funk, and dance music. If people can open their ears to the different textures and timbres, I think the hypnotic grooves would be very appealing [to them]. Fortunately, one of the positive effects that the Internet has had on [the music industry] is [that it has created] an explosion of awareness and access to [the] music of different cultures via recordings, both old and new. I often have conversations with people who I’m surprised to learn are interested in obscure artists or [musical] styles from different parts of the world.

What would you say is uniquely ‘Moroccan’ about these recordings? What makes them stand out in particular?

Although the six tracks included on Kassidat are wide-ranging [in terms of] styles and regions, they share a lot of common musical traits. The songs [feature] similar scales, and – more importantly, perhaps – [similar] rhythms. Complex polyrhythms and syncopated hand-clapping are commonly used across [the] regions [presented]. Another uniquely Moroccan trait is the use of the gunbri, a stringed lute that is native to Morocco and [that] comes in several shapes and sizes. Finally, the use of Amazigh dialects (sometimes mixed with Arabic) is very much a part of [traditional] Moroccan music.

I think that one reason people have been excited about Kassidat is that this is really the first reissue of its kind … the format of a single CD or LP is too limited to really explore the intricacies of a music complex as Moroccan folk, but it’s a nice introduction [nonetheless]

To what would you attribute the interest in this type of music outside Morocco?

I’m not sure that [this type of music] is popular in many countries; as far as I understand it, this older Moroccan folk music is barely known outside the region, with the exception of the Moroccan diaspora. Although [the late American composer, author, and translator] Paul Bowles, and later Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones recorded and issued Moroccan folk music, the impact of their recordings was limited. In the case of Bowles, his recordings were not widely heard, whereas Jones’ recordings of the musicians of Joujouka enjoyed [some] popularity in the mainstream world music market; [these were] only limited [fragments] of the huge tapestry of [musical] styles found in Morocco, [though].

I think that one reason people have been excited about Kassidat is that this is really the first reissue of its kind. Admittedly, the format of a single CD or LP is too limited to really explore the intricacies of a music complex as Moroccan folk, but it’s a nice introduction [nonetheless].

Could you provide a bit of background information on some of the more popular Moroccan pop singers featured on the album?

One interesting performer was Rais Haj Omar Wahrouch. He was born in the mountains outside of Marrakech in 1933, and began performing at an early age in the regional style known as rwais. He joined the troupe of Rais Moulay Ali, a well-known band leader at the time in Marrakech, where rwais was the reigning style. Wahrouch spent time in jail for his politically-charged lyrics, and was popular enough to tour Europe in the mid-60s. Another interesting figure, who, like Wahrouch, is virtually unknown outside of Morocco is Abdellah el Magana, a popular goual (lit. ‘storyteller’) and musician from Oujda in Eastern Morocco, near the Algerian border. Magana was known throughout Oujda for his provocative songs, [and] was unmatched in his knowledge of the city’s politics and gossip, weaving facts, rumours, and history into his songs. Like Wahrouch and many other Moroccan singers and storytellers, part of his role [entailed] spreading news, information, and commentaries about contemporary events. There are so many fantastic Moroccan performers, [and] I would love to know [all their stories], but unfortunately, knowledge of these [sorts of] details is quickly disappearing.

Do you believe such projects can encourage the understanding and appreciation of different cultures?

This is hard to answer, because I can only speak from my own experiences. I do think music is a window into another culture, but, [as with] any window, your view from it is limited. The music of any culture is connected to many other things; its history, social patterns, mythology, language, food, and [so on]. If we can learn about the music, we [will] invariably end up learning about these [other] interconnected [aspects] as well.