Her eyes were shut, her cheeks wet … The hair was falling on his knee and on the white sheet … ‘Just like Googoosh,’ he whispered

The young man reached into his Kurdish pants pocket, pulled out some cash from among the business cards, receipts, and other folded papers, and put his small black pouch on the counter, next to the scale.

‘Two thousand and three.’ The fruit vendor licked his upper lip on which there was a huge red moustache and looked obliquely at the man’s grey, baggy pants.

The man unfolded the banknotes only to see some long, black strands of hair between them. Despite the cold, sweat dropped from his left temple onto his one-week-old beard and hollow cheeks. Then, he paused.

An old man next to him handed his shopping bags to the fruit vendor. The man with the red moustache put them on the digital scale one by one and pressed the buttons on the display. The vendor looked again at the young man who was staring at the strands of hair between his fingers.

‘Two thousand and three hundred tomans!’ the fruit vendor said, raising an eyebrow, startling the young man. ‘Two and three,’ the vendor repeated, looking irritated.

‘Prices soar every second,’ the young man said, as if talking to himself.

‘Been the same for the last two weeks,’ the vendor said.

‘Here you go.’ The man put the strands of hair in his pocket and gave the vendor all the cash he had in his hand, and the vendor threw it into the rusted drawer of the counter under the scale.

The man picked up the bags of potatoes, onions, and eggplants. He was stepping out of the store when the cell phone in his large pocket rang. He looked at its display, which read “Chonour” and pressed the green button.

‘Allo! … Near home … No! … Please, don’t start again, please … You might be comfortable, but she isn’t.’ The cold weather turned his hands crimson while he carefully picked his steps in the snow in the dark narrow alley. ‘Chonour! You think I have forgotten how you’d imprison yourself every time you had a few pimples on your face?’ The man stopped, remembered something. He put down the grocery bags, searched his pockets one by one, turned them inside out. ‘Hold on,’ he whispered to the cell, picked up the bags and ran back to the counter where the digital scale stood.

‘My pouch?’ the man asked, looking around. ‘I had a small black pouch here.’

The fruit vendor was counting some cash and did not respond. A woman in a long, Kurdish dress was bent over a box of big and almost rotten cucumbers, carefully selecting some. The man’s knees hit her while he was leaving the store in a hurry, still holding the cell and the grocery bags.

‘You blind?’ The woman turned her head, her cheeks and nose red from the cold. The man remained speechless, looking at her thick black hair pouring out of the headscarf and onto her waist.

About ten steps further, he reached the last customer who’d left the store, an old man walking with a crutch, carrying a few tomatoes in a white bag.

‘Agha … Agha! I had a small pouch there.’ The man looked at the tomatoes and pointed at the store. He didn’t see when the old man shrugged because he stuck the cell to his ear and shouted, ‘Allo! … Allo!’ The display was dark.

The man ran to the fruit vendor again. ‘Agha! My pouch. Didn’t you see my pouch?’ he implored.

The fruit vendor with a sly smile on his face took a black bag out of his rusty drawer. ‘Is this the one?’

The man grabbed the pouch, frowning. His cell rang again, and he answered it. ‘Slaw, sorry … Look! She is not in a position to party … she doesn’t like anybody to see her.’

He reached the door of a building, looked up, and stepped back. ‘Listen, sis, I’d like to go with you and I know that I should, but I can’t leave her alone … Why don’t you understand?’

The curtains of the fourth floor were pulled down and the lights were off. ‘What’s that?’

He frowned, raised his head to hold the cell to his ear, took the key out of his pocket and stepped forward to open the door. ‘It’s not zesht! Who the hell are these relatives anyway? Why do we have to be there for them all the time, when they left us alone after father’s death? Where the hell were they when Mom was in the hospital?’ Closing the door, he continued talking. ‘Whatever! Tell them my brother can’t go anywhere without his wife’s permission. Tell everyone my brother is a miserable, docile, weak man. Tell ’em he’s not a man at all, if that makes you happy.’ He pressed the red button and was about to crush the phone against the wall.

Standing on his knees, he touched her hair, took off her hairclip, and spread the hair over her shoulder. He bent her head forward and stared at the white hairless area that was spreading, taking an ever greater share of her head

He turned on the hallway lights and noticed the loud music. He turned them on again when he reached the third floor, since they had automatically turned off. In front of the door, there were dozens of shoes. He stopped for a moment and heard the voice inside the apartment. ‘No one can resist dancing to this song.’

The man climbed the stairs slowly, listening to the people’s applause and hurrahs. He smiled. His pouch fell and slipped down three stairs. The man climbed down, picked it up and continued climbing. People inside the apartment persisted with their calls of happiness. He didn’t look back any more.

When he reached the fourth floor, he buzzed and waited a few minutes. He put down the grocery bags, and tucked the black pouch under his armpit. He was turning the key in the door when a frail, slim woman in a white Kurdish dress and headscarf opened the door. Her blue velvet vest was entirely embroidered in bands of multicoloured flowers. She said hello and reached out to grab the bags.

‘No, no. I’ll take ’em,’ the man bent and kissed her forehead. ’I can,’ the woman whispered. ’You can,’ he replied. He gave her one small bag, looking at her red nose and cheeks. She went in quickly. He put the black pouch in his coat pocket, picked up the other bags and went in. She was not in the living room. He went to the kitchen. She was washing some dishes. He stayed there for a moment. ‘I’ll wash ’em.’

‘I can,’ she said, not turning to him.

He pulled on the handle of the fridge door and said, ‘This is broken. I should fix it.’ He bent down, hands on knees, and looked inside. There was a jar and a bottle of water, a can of tuna and some bread.

‘Good news!’ He took the bottle and sipped the water. ‘Our loan is approved. See how lucky we are?’ He put his hand on her shoulder. ‘We got absolutely nothing to worry about, aziz. Also, we have a chance of getting reimbursed for the new medication.’ She kept washing.

The man put the bottle down on the counter top, left for the bed- room and hung his coat. He took the pouch out of his pocket, stretched his hand and touched the object inside. His eyes stared into space, lips moving and right foot trembling. He looked at the kitchen door and then at the pouch. The cell rang. He saw the name ‘Chonour’ on the display.

‘Allo.’ He held his thumb on the red button for a few seconds. The screen went dark.

‘Wrong number.’ He turned towards the kitchen and saw the corner of the woman’s white dress quickly flitting by the door.

He crouched down, turned on the TV, picked up a video from a pile and put it into the player. The man leaned on the cushion and stretched his legs, looked at the small screen of the old TV, and glanced at the pile of moving boxes in the other corner of the room. On the top box lay a wooden framed wedding picture. The man and the woman were holding hands and smiling at the photographer. The bride’s hair flowed down to her waist. No voice from the kitchen.

‘Fermisk! Your beloved is singing, Fermisk!’ he called out. She came to the kitchen door, drying her hands. ’Come, sit here,’ he patted the carpet. She hung the towel on the handle of the door and sat where he had indicated. She looked at the TV and he at her.

‘I know you don’t feel too comfortable in this place but, you know, nobody knows us here and the rent is reasonable.’

‘I know all this.’ She looked at the TV screen and hummed a sad song along with Googoosh.

He tried to draw her headscarf back, but its knot kept it in place. He untied it while looking at her profile.

‘I’ll buy you the blue scarf I promised,’ he said.

‘Oh, I’d forgotten about that.’

’I haven’t.’

She held his wrist when he finished untying the scarf. He stared at her. Her face was dry but her eyes were red and her eyelids swollen. She freed his hand, and he took off her scarf and held her head across from his face. Standing on his knees, he touched her hair, took off her hairclip, and spread the hair over her shoulder. He bent her head forward and stared at the white hairless area that was spreading, taking an ever greater share of her head.

‘It doesn’t show, if … you … tie your hair like that.’ He swallowed.

‘Tie what hair, Diako?’ she pulled the scarf back on her head.

‘Well … it can’t go on like this.’

She hummed with Googoosh. ‘Bezar ghesmat konim tanhai moono…’*

‘You mustn’t cry for this every night, gian,’ he continued. ‘You are not in pain any more, are you?’

‘You just can’t stand my hair loss, can you?’ she said, still looking at Googoosh.

‘What are you talking about, aziz?’

‘I know, you have a thing for hair.’

‘Fermisk gian, you’re beautiful with or without hair.’

’Oh, I am not blind, Diako.’

’You see … yes … I mean no … I mean it’s not nice to have hair on some parts of your head … and not on the …’

‘Where have you hidden the mirrors? You thought I wouldn’t notice,’ she suddenly yelled, peeling herself away from him.

‘Heh, I did that to my hair after I watched that clip of Googoosh you just talked about. My mom beat me up.’ She smirked. ‘I will look like a boy …’

‘Fermisk gian, Fermisk.’ Diako held her face in his palms. ‘I haven’t hidden anything from you.’

’Yes, you have. There isn’t one single mirror in this place. But I still see myself in the window. I know what I look like.’

‘No, you don’t. You have no idea how beautiful you are,’ he said.

‘You just said it’s not nice to be bald.’ She put her hands on his, which were still on her cheeks.

‘I was just gonna say you could be like Googoosh.’

’Like who?’ she gaped.

’Look!’ He said. ‘There is a show where … she is so attractive … she … she has shaved her hair. She’s beautiful, isn’t she?’

‘She hasn’t quite shaved her head. But, that’s a very short haircut which I have always liked. You never let me cut my hair short like that.’

’You’ll love it!’ He hesitated. ‘It would be … great … Let’s try it … you will look super attractive. I am sure.’

She wiped a tear in the corner of her eye. ‘You remember my childhood picture with shaved hair?’ She smiled.

‘I do. You looked even prettier than Googoosh.’ He kissed her hand.

She ran her hand through her hair and looked down at the mass of black strands in her fingers. ‘Heh, I did that to my hair after I watched that clip of Googoosh you just talked about. My mom beat me up.’ She smirked. ‘I will look like a boy, you’re not gonna like …’

He kissed her on her lips.

She drew her head back. ‘Hey, I was in my childhood streets last night.’

‘Where?’

‘Those old streets. I dreamt there was a flood.’ She leaned her head on his shoulder. ‘The water was very clean but they said it was sewage. I was in it.’

‘Who said so?’ He patted her head.

‘I don’t know.’

‘Was I in your dream, too?’

’I was all by myself,’ she said, shaking her head. They were both silent.

‘Diako?’ she asked.

‘Gian?’ He gently patted her head.

’If I ever get better …’

‘You will, bawanm, you will, and your beautiful hair will grow back,’ he kissed her forehead.

‘Say, what did you say to my mom?’

’I told her the truth.’

‘You told her the truth?’ She lifted her head and looked into his eyes.

’Not like that! She said she’s gonna visit. I tried to tell her something so she would not be surprised when she sees you with a headscarf at home,’ he said.

‘Oh, what did you say, then?’ Fermisk asked.

’I said you have been to a contaminated swimming pool.’

‘She knows I don’t swim.’

’Well, I said you had been there once,’ he said.

‘You think she believed you?’

’What else could I say?’

’Don’t know,’ she shrugged. ‘I’ll never tell her the truth.’

‘We shouldn’t. She can’t take it.’

‘I’ll put on one of those scarves with a hat for my brother’s memorial day.’

‘Do so, azizam.’

‘Buy me a wig.’

’I will, gianakam.’ He pulled her in his arms.

‘What colour will you buy?’

’The colour of your own hair,’ he said.

‘Naah, buy me a new colour, but a nice one.’ She put her hand through her hair then looked down at the clump she had brought out. ‘Let’s stick this hair in again and not pay extra money for the wig,’ she laughed. He squeezed her and pressed his cheek to her pale cheek.

‘Hey, don’t break my bones.’

‘Let me bring a sheet.’

‘All right,’ she said.

He fetched his small black pouch and a sheet and sat behind Fermisk.

Diako spread the white sheet on the floor. She sat in the middle of it, facing the TV screen. He withdrew a silver metal object out of the black bag and took its two long handles between his thumb and forefinger. He stood on his knees, held Fermisk’s hair between his hands, swallowed, lifted her hair and covered his face in it. Fermisk turned to him. Diako saw his reflection in the screen of the television.

‘Turn,’ he said.

‘Why don’t you turn?’ Fermisk asked.

‘Turn, please.’

She placed her palms on the carpet and turned her body around.

Diako sat on his knees. He took her hair in his left hand and the metal piece in his right. He stood up, sat down again, and stood up once more. Diako fetched a chair, placed it behind her and sat down on it. ‘Sit on your knees.’

‘Yes, Ghorban!’

He put her hair on his lap. Then, he gently pulled the strands above her ear towards himself and put them on the bald part of her head. Diako placed his fingers on Fermisk’s forehead and pushed her head back on his lap. She resisted. He kissed the place between her brows. Her eyes were shut, her cheeks wet. He pushed her head forward tenderly and started from where the bald spot was spreading in her hair. The silver-white cold metal went on and on. The hair was falling on his knee and on the white sheet. His hands were trembling. ‘Just like Googoosh,’ he whispered.

* A line from the song Pol (Bridge) - Let’s share our loneliness …

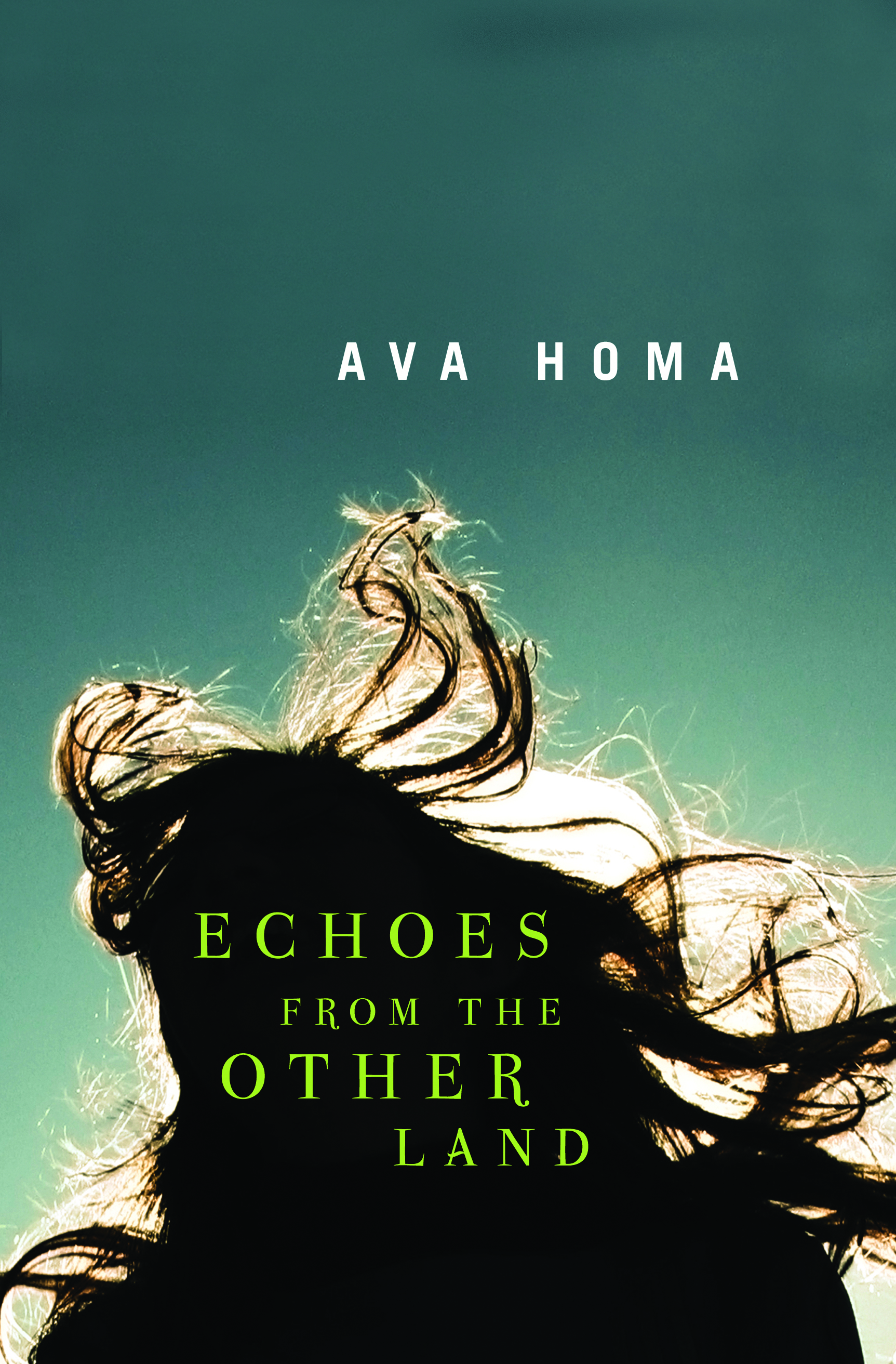

From Echoes from the Other Land