Zakaria Ramhani’s reflections on portraiture, Islam, language, and identity

Images courtesy Julie Meneret Gallery

Lost among the roses, nightingales, flowing cypresses, and drunken lovers of Persia’s miniature masters of old, one often forgets - if they are aware, that is - about the dark secrets these flowery delights conceal. According to legend, after their careers as painters of all that was sumptuous, rapturous, and in many cases, downright hedonistic, these artists would spend their old age in repentance of their ‘sins’, even going so far as burning the remnants of their works, at times; for though the patrons and artists of miniature painting (as well as other art forms, for that matter) of the era had a weakness for the cup-bearer’s winding curls and the sight of the fair Shirin bathing in the wild, their passions were more often than not in defiance of the orthodox Islam they knew.

The tension between the depiction of sentient beings and rigid interpretations of orthodox Islam has existed for centuries, and is one which has manifested itself in variegated forms throught history. The Byzantine icons of the Hagia Sophia, the Buddhist images of Bamiyan (the statues are another story), the Safavid frescoes of Esfahan, and countless other depictions of beings earthly and divine, in what is today known as the ‘Islamic World’, were all at one point smothered with clay, at the hands of new rulers charged with religious fervour; some have, in recent years, seen again the light of day, while others, less fortunately, still remain in the void of the unseen.

In his novel, My Name is Red, Orhan Pamuk brilliantly illustrated this tension, through a heady mixture of mystery, philosophy, and a lush telling of the history of the Persian miniature tradition. As per the plot of the book, the Ottoman Sultan commissioned a group of artists to produce portraits in the European style, which resulted in outrage, as well as a tangled web of conspiracy, intrigue, and murder. More recently, this tension has been again brought to light by Zakaria Ramhani, a much younger artist working in a different medium. In his first US solo exhibition currently showing at NYC’s Julie Meneret Gallery, May Allah Forgive Me, Ramhani has explored the relationship between portraiture and interpretations of orthodox Islam, as well as other subjects, including identity, language, and innocence - albeit without the Turkish drama.

Your father used to be commissioned to paint portraits from time to time in Morocco - a practice that was the source of much guilt and anxiety for him. With the title of your exhibition serving as a reference to this, as well as the broader ‘conflict’ between orthodox Islam and portraiture, would you say you also feel a sense of guilt as an artist whose subjects are mostly individuals?

I think that this feeling of guilt is today part of a collective mental ‘heritage’; the influence of Islam and its theological perception of existence are in fact major forces that have influenced to this day a lot of Arab art. But individual experiences are also today expressed through art, so figurative painting – which hasn’t existed for more than 200 years in the Arab world – is in a way contradictory to orthodox Islam, which is why even today there are identity issues surrounding it.

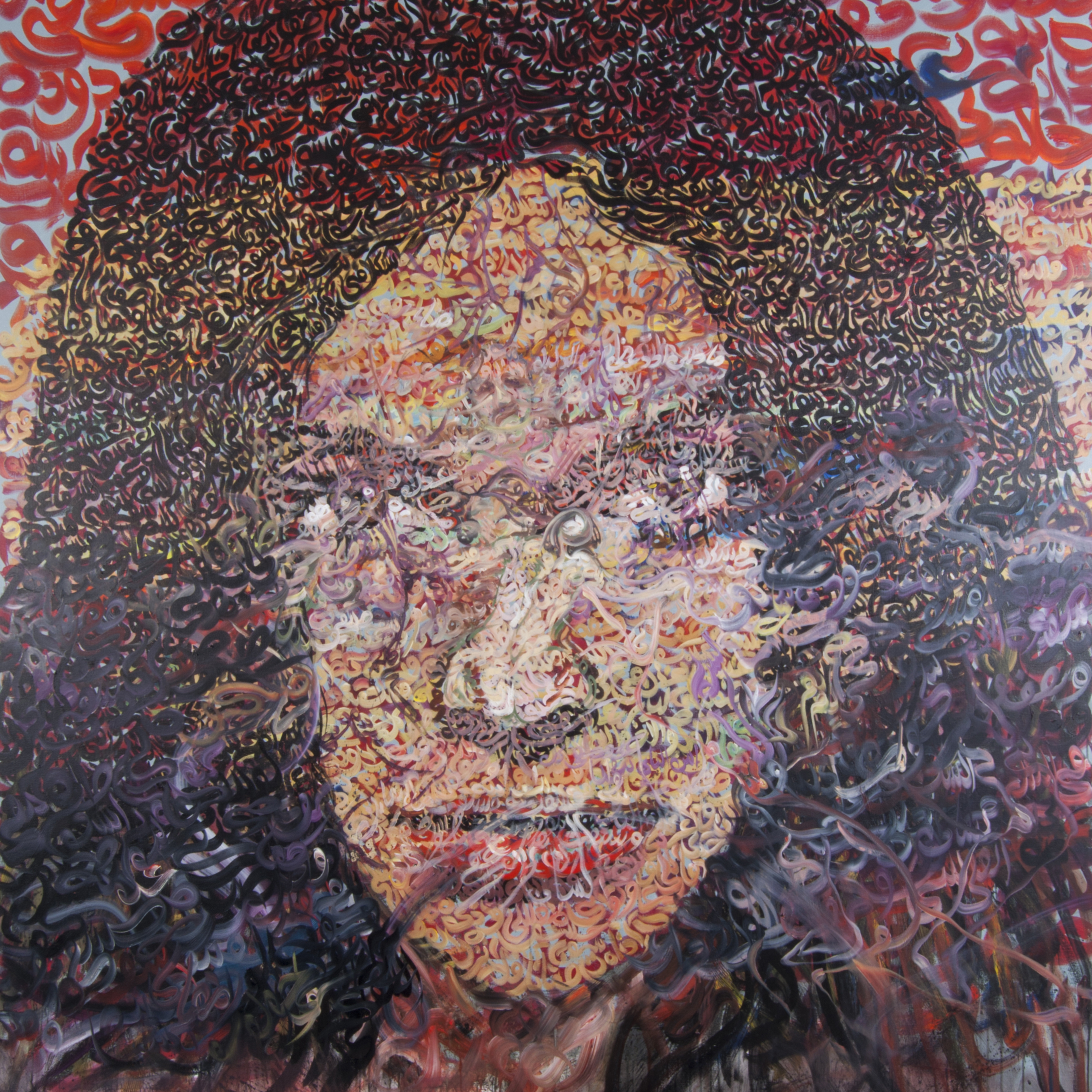

The Unknown General

How do you view the longstanding tension between portraiture – and any visual representation of beings, for that matter – and orthodox Islam? How do you manage to reconcile the two?

I think that this specific tension has turned into a problematic question of aesthetics; the creation of visual figurative artworks that represent the human form with elements that had at a time made them forbidden is in a way a trompe-l’oeil for me. It at once represents a reflection on the possible reconciliation between words and figurative forms coming from the visual heritage of two different civilisations, in such a way that makes it possible to question the issue from two opposing directions. In my works, calligraphy has become painting and portraiture; but portraiture, as an Occidental form of art, has turned into something else in my paintings, with respect to traditional European art. One sees these portraits with another ‘eye’, and this is where the idea of ‘otherness’ comes into play.

Growing up in a Muslim household in a relatively conservative environment in Tangier, your surroundings weren’t exactly conducive to a life as an artist; yet, you managed to become your country’s youngest artist to be awarded a residency at the Cite International des Artes in Paris, and have exhibited your works around the world. What has been the driving force behind your practice as an artist?

I think that every artist is stimulated by different elements in their desire for achievement. I prefer to think of my past – as well as my present – as a reality that is providing me with material for transformation. Is there any specific force behind creativity? Perhaps it’s the distance we try to make between ourselves and reality – from our limited state of physical existence – and the desire to leave behind something that will remain when we face the only real truth: death.

This accumulation of words that have no particular meaning is symbolic of the impossibility of understanding our own identities, and I think only a medium such as language has the capability to represent this complexity

You have a few pieces titled Faces of Your Other, which I find particularly interesting. As I mentioned in a recent interview I did with Christie’s, the works speak to me on a number of levels, especially where politics and spirituality are concerned. Could you explain the concept behind these pieces? Who are the ‘others’ you are referring to, and what are they trying to say?

Faces of Your Other is a series of paintings I did, in which I strove to replicate the human face using Arabic script. To do this, I juxtaposed words and phrases of various sizes and colours, and superimposed them on the entire surface of the canvas in a free and expressive style. In the centre of the compositions, these words and phrases form organs such as eyes, noses, mouths, ears, as well as hands, as a result of the combination of the curved and straight lines of the letters of the Arabic alphabet.

Faces of Your Other

The faces in the portraits are composed of a colourful assortment of poetry fragments, verses from the Koran, popular expressions, literary passages, inconsequential remarks, rash thoughts of mine, and made-up terms, as well as individual letters. Essentially, the natural flow of my thoughts served as material for me, which I translated onto my canvases. The ‘codes’ and formalities of classical Arabic form a sort of ornamental frieze or forgotten cuneiform script in the paintings; the circle or opening of a letter becomes an eye, handwritten inscriptions become purely visual … through the formal aspects of the Arabic script, I at once tried to transcribe and obscure the human face in its most elementary and fundamental visual form.

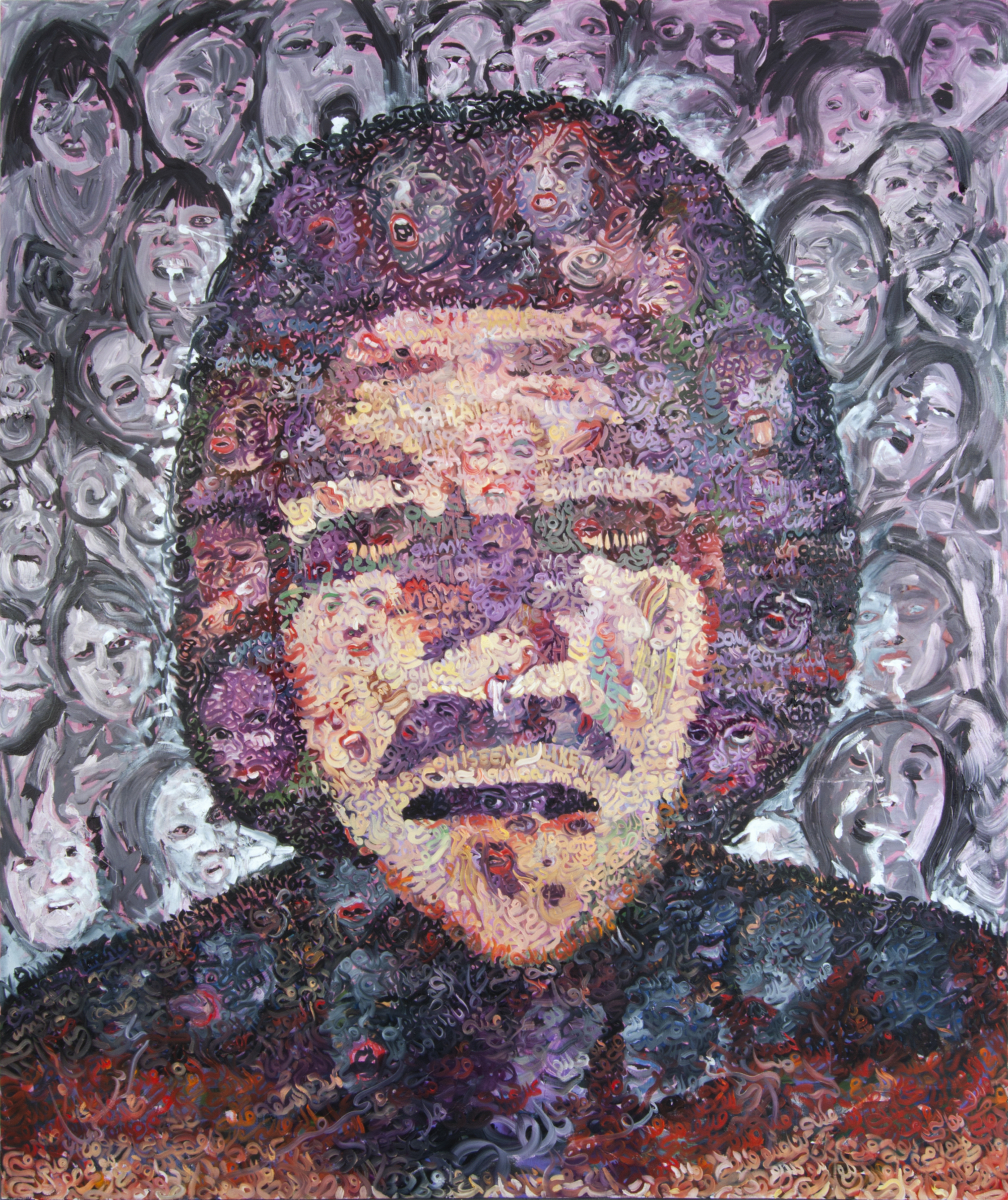

In addition to the Faces of Your Other series, you’ll also be exhibiting a few works with featuring dictators and other infamous personalities from the Arab world and beyond. Looking at the triptych of the childhood portraits of Adolf Hitler, Saddam Hussein, and Osama bin Laden, one can’t help but think, why? What sort of reaction do you hope to elicit from audiences with these particular works?

The idea was to embark on an investigation about the notions of identity and innocence. The title of the series implies a notion of guilt present in the show, which explains why I chose to depict well-known infamous personalities as children, at times during which they were still innocent.

I’m Sorry Father (Adolf, Saddam, and Osama)

What initially caught my attention was your striking use of calligraphy. You once mentioned that through your use of calligraphy, you intend to highlight the impact of language on one’s identity. Can you elaborate on this?

The linguistic meaning of the Arabic script in my works is illusory, and is intended to be illegible, even to readers of Arabic. I cull my references from a wide variety of sources and combine them into implausible and surreal scenes. The paintings deliver the elements of meaning, but lack significance. In the paintings, language ‘breaks’ apart on the surface of the canvas. This accumulation of words that have no particular meaning is symbolic of the impossibility of understanding our own identities, and I think only a medium such as language has the capability to represent this complexity.

‘May Allah Forgive Me’ runs through December 22 at Julie Meneret Gallery.