One Beirut. Two very different dolls.

As an object, the doll has something to say. Reflecting particular values and beliefs, it serves a cultural purpose. In Lebanon, where there is relatively little in terms of art, but the land itself is part of heaven, the doll is a public statement and an artistic expression. This small human replica creates a certain emotional connection, asking to be used as a medium. The doll is ever-ready to function within any context, waiting inanimately to be controlled and brought to life, such that it can open up infinite imagined realities in which its beholder finds his or herself surrounded, and perhaps, controlled by their own fantasies.

Particularly interesting is the use of the doll in the works of two prominent contemporary Lebanese artists. In the art of Mohammad El Rawas, one sees half-naked, Westernised dolls, while for the most part, they conservatively appear wearing the headscarf in the works of Zena El Khalil. Though their approaches are different, however, both artists refer to strong religious notions originating from Lebanese society in their works. While Rawas rejects the revival of conservative traditions, El Khalil covers her dolls with glitter, admitting the presence of such customs, though presenting their ‘modern’ dimensions and aspects at the same time.

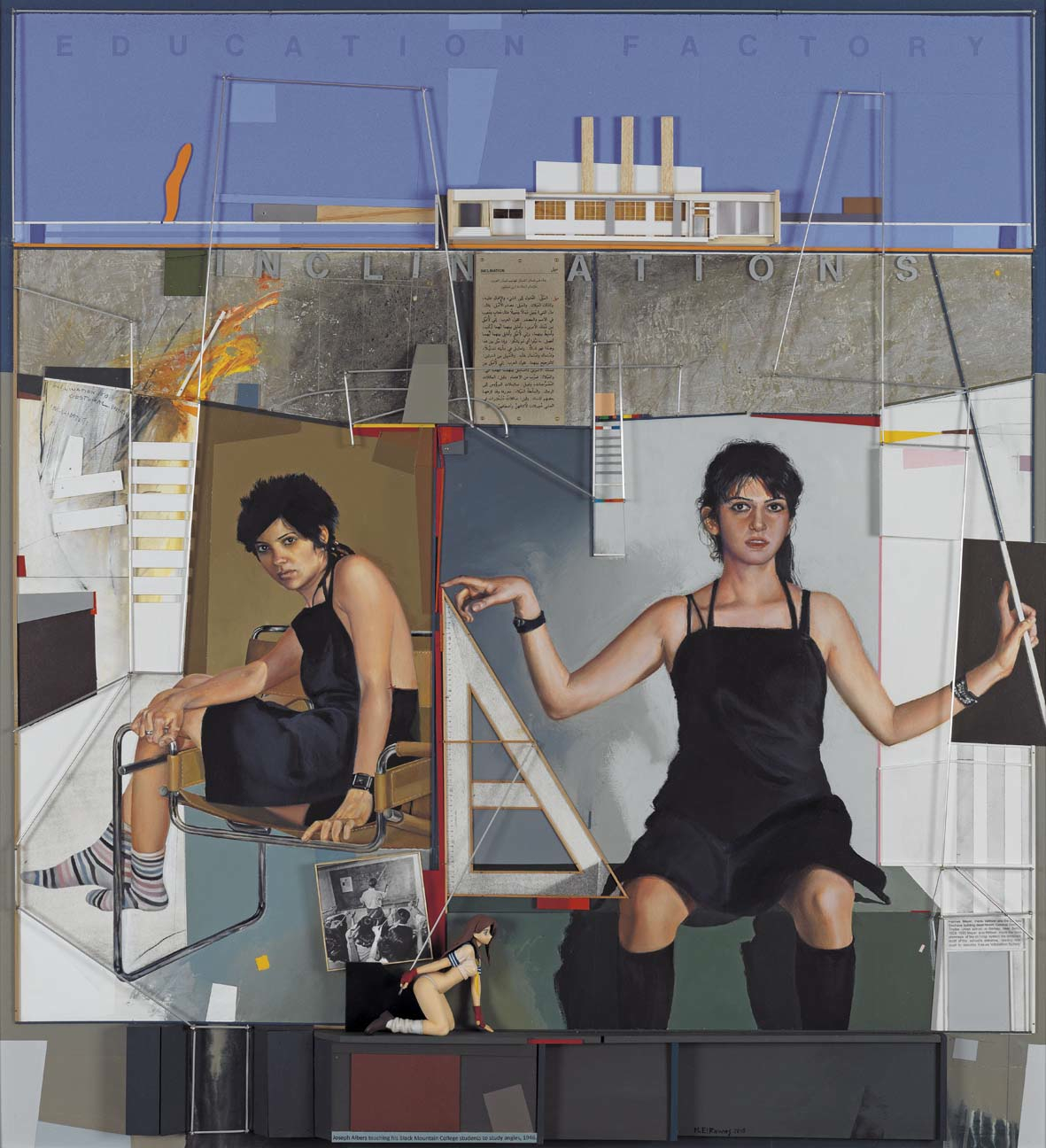

The element of playfulness in their work is a shared one, albeit each artist employs it in their own way. Rawas’ three-dimensional assemblages require audiences to unwrap several layers of meanings and codes to follow his narratives. His work leads one to follow a story, as if inside the dollhouse, the doll is presenting a Western worldview within a setting of events specific to the particular artwork in question. Though the doll in Rawas’ work is mostly based on the aesthetic of the Japanese Manga figurine, he gives it a makeover; Its hair is coloured - and perhaps cut, too - although one only sees the ‘bigger picture’ in beholding the artist’s highly and delicately polished works as a whole. In these pieces, Rawas gives the doll a specific role in a globalised world open to various cultures. Rawas’ doll switches between languages – sometimes English, sometimes French – and is aware of the current cultural situation in Lebanon. Being nestled within assemblages of historical and cultural elements, it expresses a standpoint in favour of the conceptual perspective of the work.

Mohammed Rawas - Inclinations

Rawas uses the doll in his artwork as an element of traditional storytelling that goes beyond the boundaries of contemporary Muslim Lebanese culture. Accordingly, the doll navigates between the two and three-dimensional layers, or existences of his works. The use of religious notions and historical facts in his work suggests as reshuffling of events, introducing, mixing, and contrasting cultures to create a different, ‘playful’ plot, imposing a host of other possible scenarios. Altogether, his dolls are acutely representative of the current state of today’s globalised culture.

In the works of Rawas and El Khalil, the doll becomes an object representing the juxtaposing of cultures, realities, and universes

On the other hand, the playfulness in El Khalil’s work is more or less limited to a Muslim Lebanese context, in which the doll is strictly garbed within political and cultural boundaries specific to contemporary Beirut. El Khalil’s covered doll, however, is not telling a story like that of Rawas, but rather reflecting images of a continuous situation in which it finds itself, rejoicing. The headscarves on her dolls are mostly comprised of a soft, glittering, bright pink fabric, which rather festively portrays it as a celebration of religion under the power of globalisation, further elucidating the role the hijab plays in contemporary Lebanese society. El Khalil’s works are attractive, colourful, and vibrant at first sight; however, upon second glance, the cultural tragedies within them float to the surface. In her works, the artist projects her love/hate relationship with Beirut in a politically-charged manner, depicting popular religious and military figures. Representative of a confused society, El Khalil vests in her dolls a girlish power, in an attempt to childishly provoke audiences into a political and religious dialogue.

El Khalil’s dolls are surrounded by everyday objects particular to her environment, which aim to penetrate the consciousness of the masses in a joyful gesture. El Khalil covers all the disastrous memories and lingering facts of the Lebanon she knows in a gleaming pink, and the banality one would see in a typically decorated Beirut store window. She is an artist who embraces the future with a foot steadily entrenched in a traditional past.

Although El Khalil’s dolls wear the hijab, she reassures the viewer that they are not generically Muslim, but culturally Lebanese, specific to Beirut and its unique, complex society. Though they appear as flashy, localised Western products, they continue their religious practices as responsible Muslims. In pieces featuring multiple dolls, a festive gathering of religious and political elements particular to Muslim Lebanese society is portrayed, urging audiences to acknowledge various societal contradictions in Beirut.

Zena El Khalil - Paradise (detail)

In the framework of Muslim Lebanese society, the dolls in El Khalil’s work reflect the presence of a group that finds itself in-between cultures, being neither completely Western, nor strictly conservative in the Eastern sense. Within the confusion of this Muslim Lebanese identity, these devout dolls have most probably been excluded from the Muslim community; nevertheless, they are shiny and happy. In the end, however, they acknowledge their role within the grander sphere of contemporary Islam, whereas Rawas’ Manga dolls seem to be resisting Islamic culture in Lebanon.

Perhaps the difference in the use of the doll in the work of these two artists can partly be attributed to their age. El Khalil is several generations younger than Rawas, and a living product of the culture of her subjects. Her dolls lead one to question the current climate of cultural contestation in Lebanon, and the present revival of past practices and traditions. At the same time, however, one also witnesses through her works the ‘progression’ and Westernisation of these old-fashioned practices in the contemporary age.

In the works of Rawas and El Khalil, the doll becomes an object representing the juxtaposing of cultures, realities, and universes, as well as a medium for the creation of various contexts and positions within these realms.