Around the world with Moroccan-French artist Bouchra Khalili

Many know what the world is supposed to look like. Children grow up learning about global geography through atlases and globes they can turn on their axes in hundreds of different directions to discover distant countries many thousands of miles away from them. Historically, global cartography has changed repeatedly over time, and while some would think of maps as silent and unmovable objects, Bouchra Khalili’s video art gives voices to maps to reveal journeys many would struggle to find in any book, whether historical or contemporary.

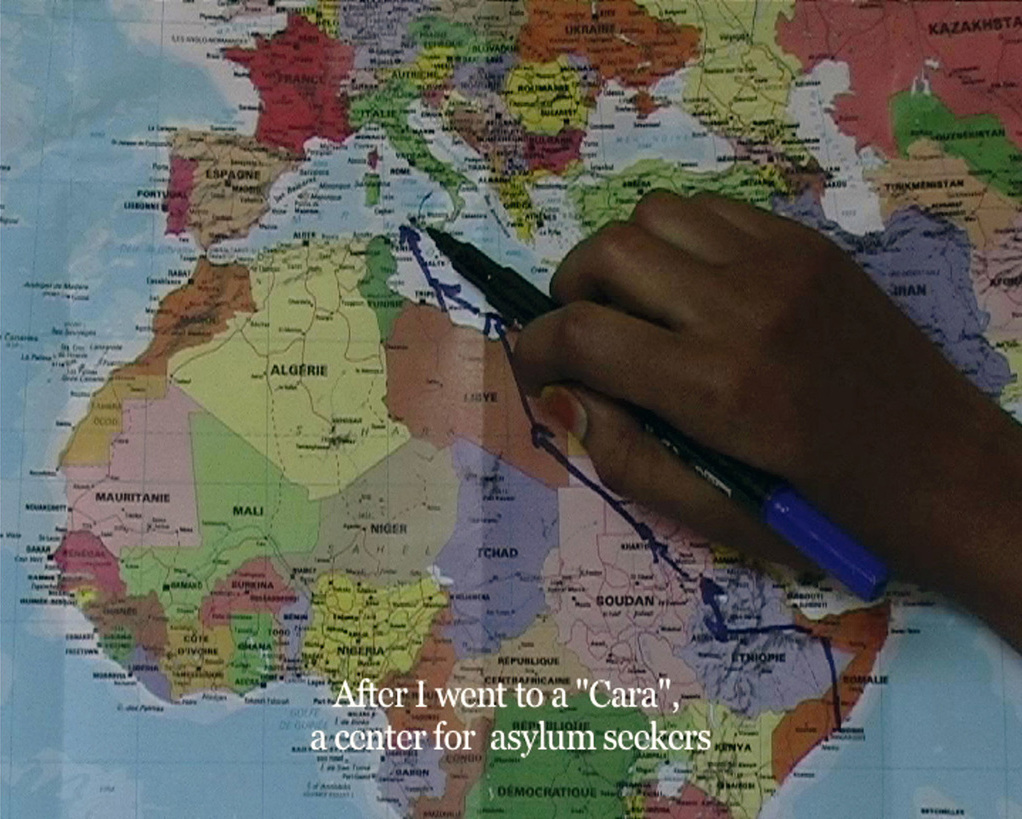

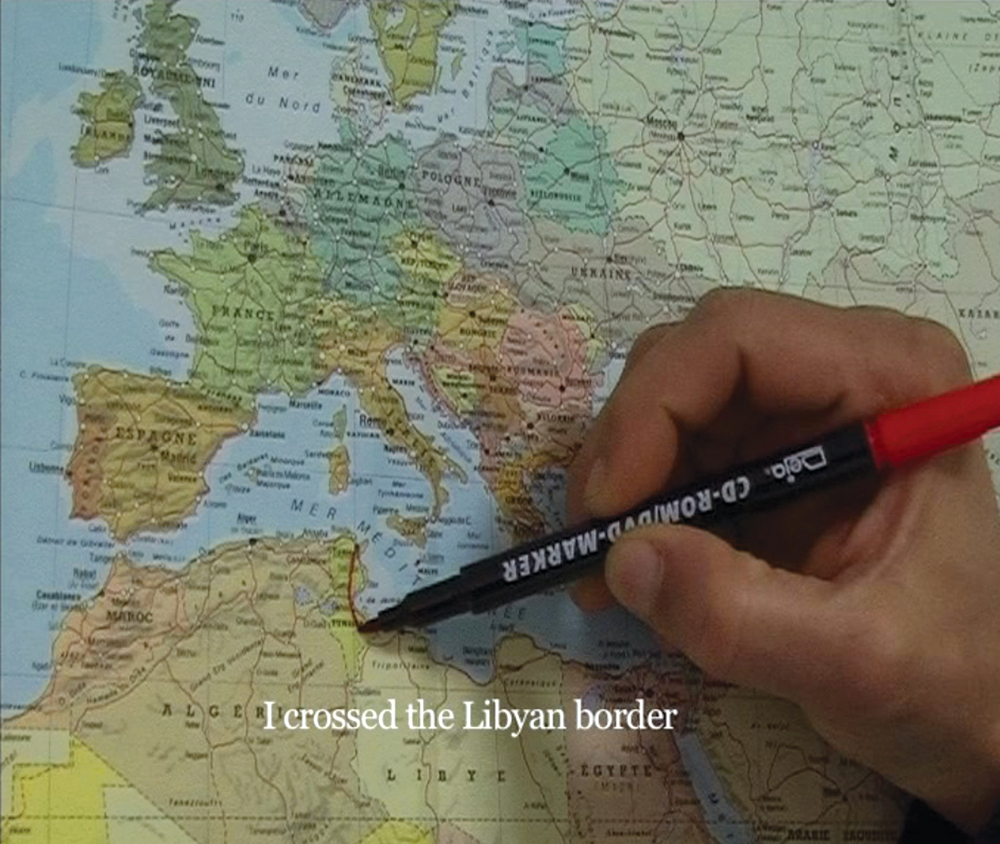

Currently suspended from the ceiling of London’s Lisson Gallery are eight flat screens, each of which projects a map in the dimly lit space. The images that flicker across the monitors are all different. The maps illustrate individual journeys to the viewer, which have taken place across the Mediterranean at some point within the last decade. Each screen plays a video that comprises The Mapping Journey Project series of videos made by Khalili between 2008 and 2011. The films have been recorded from above, such that a flat map serves as a backdrop, on top of which eight different hands plot eight individual voyages. The hands record thick black points across many different continents, countries, and seas, and are all accompanied by the voiceovers of their owners recounting the stories of their expeditions. The voices – some male, and some female – are all unique. While a few of the stories are told in English, many have been translated from various languages in the form of subtitles that appear at the bottom of the projection. Some of these speeches are hopeful, whereas others are tired.

A still from The Mapping Journey Project (courtesy Lisson Gallery)

These voices belong to refugees who, for whatever reason, have decided to leave their homelands illegally in search of other lives; and, although her own travels have been made legally, Khalili is no stranger to crossing borders. She was born in Casablanca in 1975, studied in Paris, and has lived in Germany and Norway. In a talk given by the artist in London in 2010, Khalili explained that the aim of the series was to plot an alternative map of the Mediterranean ‘not under the control of the usual tools used by geographers, but an alternative [one] shaped by clandestinity, and built around clandestine experiences and clandestine existences’. The word ‘clandestine’ implies secrets; yet, Khalili’s documentary pieces ask dozens of questions. Who are these people? Their names, ages, and backgrounds are all unknown. Despite this, the works present intimate portraits made even more private in the ways their secrets are revealed to viewers. Headphones are supplied for the journeys to unravel in their ears, such that nobody else can hear them. A typical portrait reflects the sitter’s face, but Khalili’s impressions move away from superficial adornments to highlight the voice. One doesn’t even know what clothes these people are wearing; they can only gauge scant information from a watch on a wrist or a ring on a finger.

The subjects of The Mapping Journey Project were not cast; all are people Khalili met by chance through allowing herself to get lost in cities at various points of transit. The films contain no editing whatsoever, and display a particular candour. Khalili has added no comments, and there are little traces of any ulterior motives; she has no need to add to her footage. Her recordings are multilayered as a result of having drawn journeys on top of a paper map. In one clip, a speaker is heard saying, ‘I just want to stay, have a normal life, I just hope they give me paper to stay’. Deductions are left for audiences to make.

A still from The Mapping Journey Project (courtesy Lisson Gallery)

The journeys traced upon Khalili’s maps traverse a number of countries, including France, Italy, Palestine, Spain, Russia, and Turkey. The first point of departure chosen by the artist was Marseille, as it has long been a site of transition and movement between North Africa and Europe. The films draw on centuries-old traditions of mapmaking to challenge ideas of borders and national identity. Khalili’s films also illustrate how cross-border travel has impacted language over time. Her subjects can be heard speaking a range of languages; in one video, a speaker says in a mélange of Arabic and French, ‘burning illegally’, implying that by passing illegally, one literally ‘burns’ a border. The inclusion of different tongues and varieties of languages is not only a commentary on the diversity of countries surrounding the Mediterranean, but also a reflection of the colonisation of language.

Through the rawness and sincerity of her work, Khalili reveals personal insights into the lives of those who are often forgotten

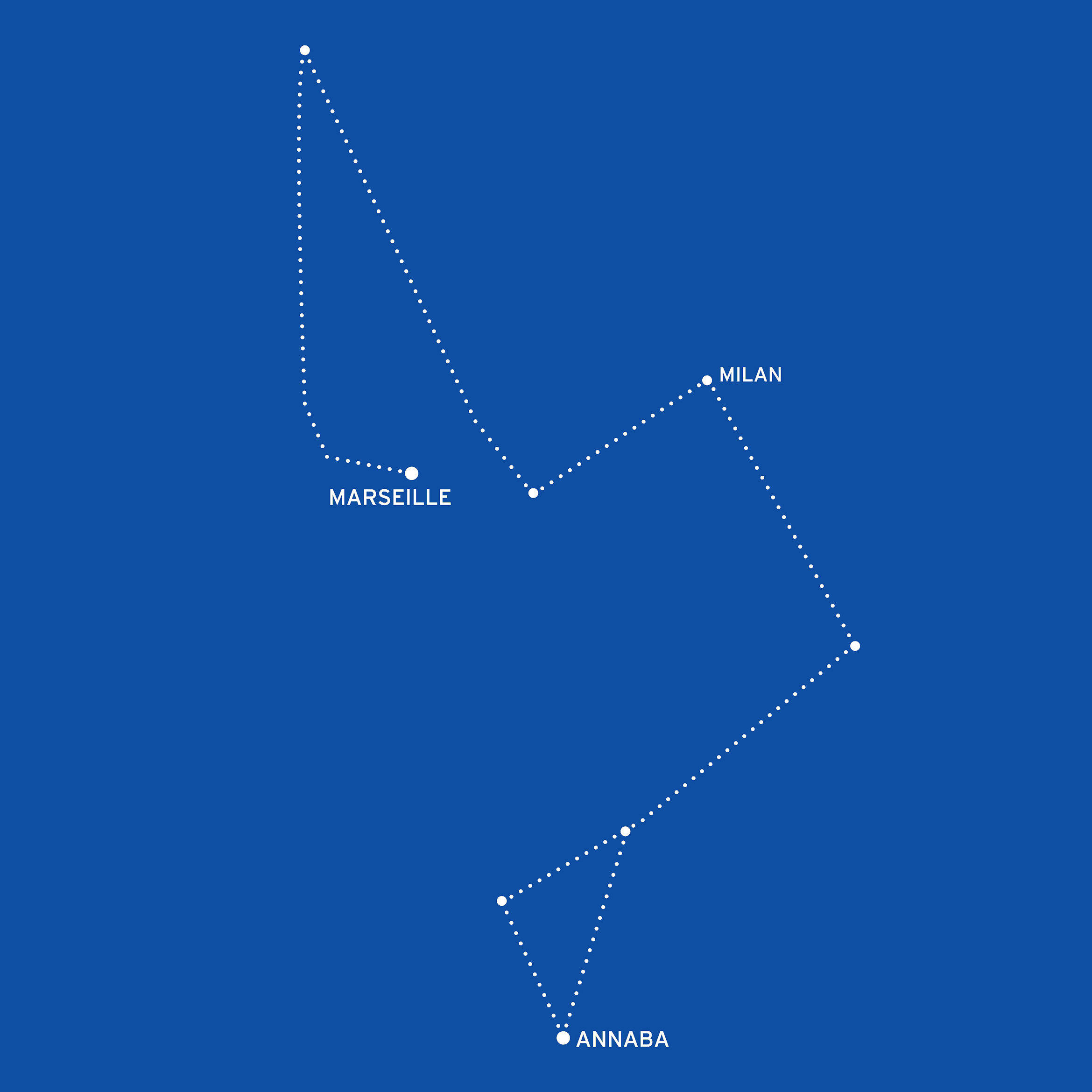

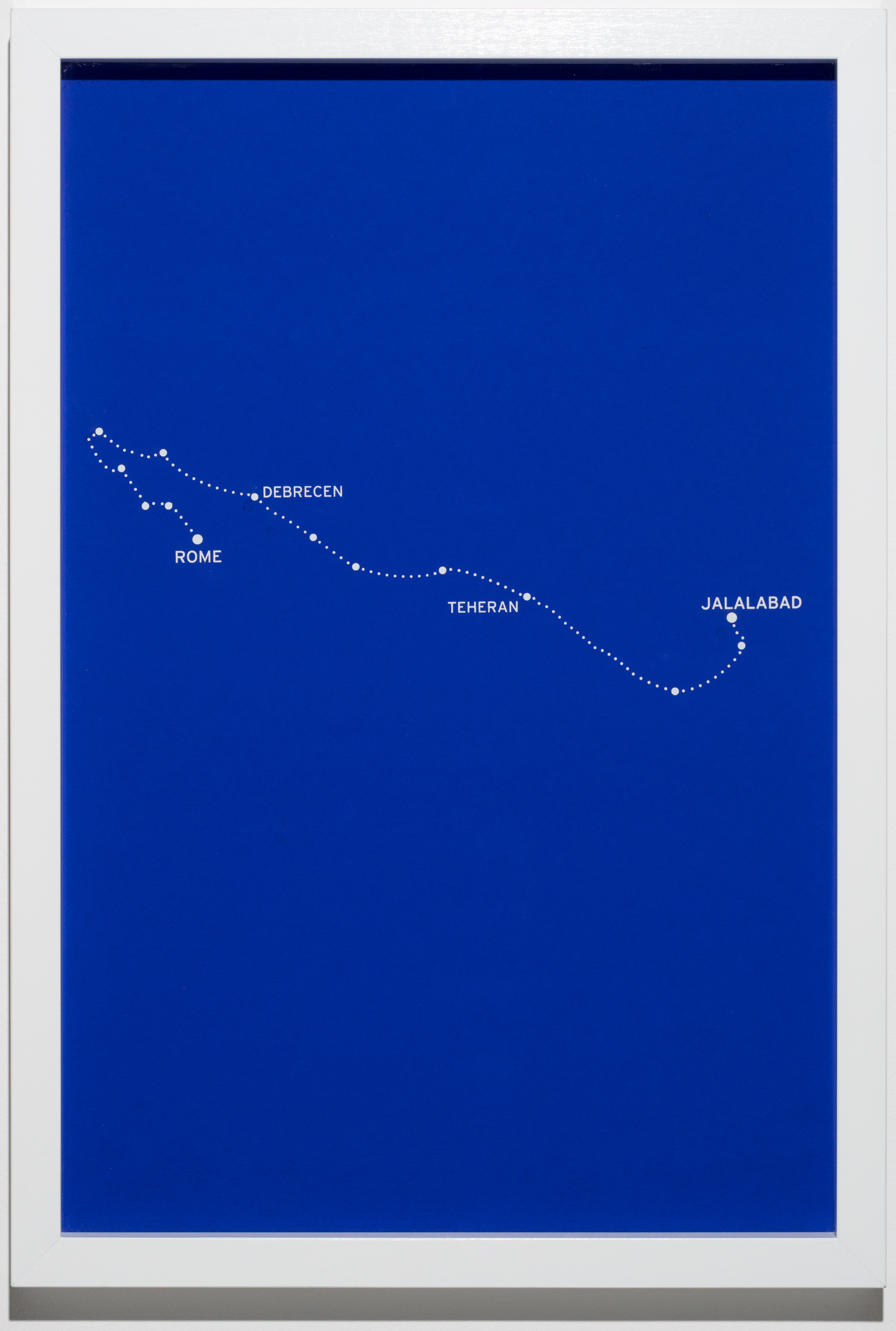

The various stopping points made by Khalili’s travellers are plotted on the maps with a cross. They may be compared to stars, and the artist has mirrored these in the form of geographical constellations, displayed on a wall viewers pass by upon entering the gallery. These astral projections are titled The Constellation Series, and comprise a series of eight silkscreen prints with white stars plotted across a deep blue sky. It is noteworthy that these constellations have been recorded against blue and not black; perhaps the choice of colour was intended to serve as a reflection of the seas that the subjects of The Mapping Journey Project had passed during their journeys across borders.

Fig. 6 (from the Constellation Series; courtesy Lisson Gallery)

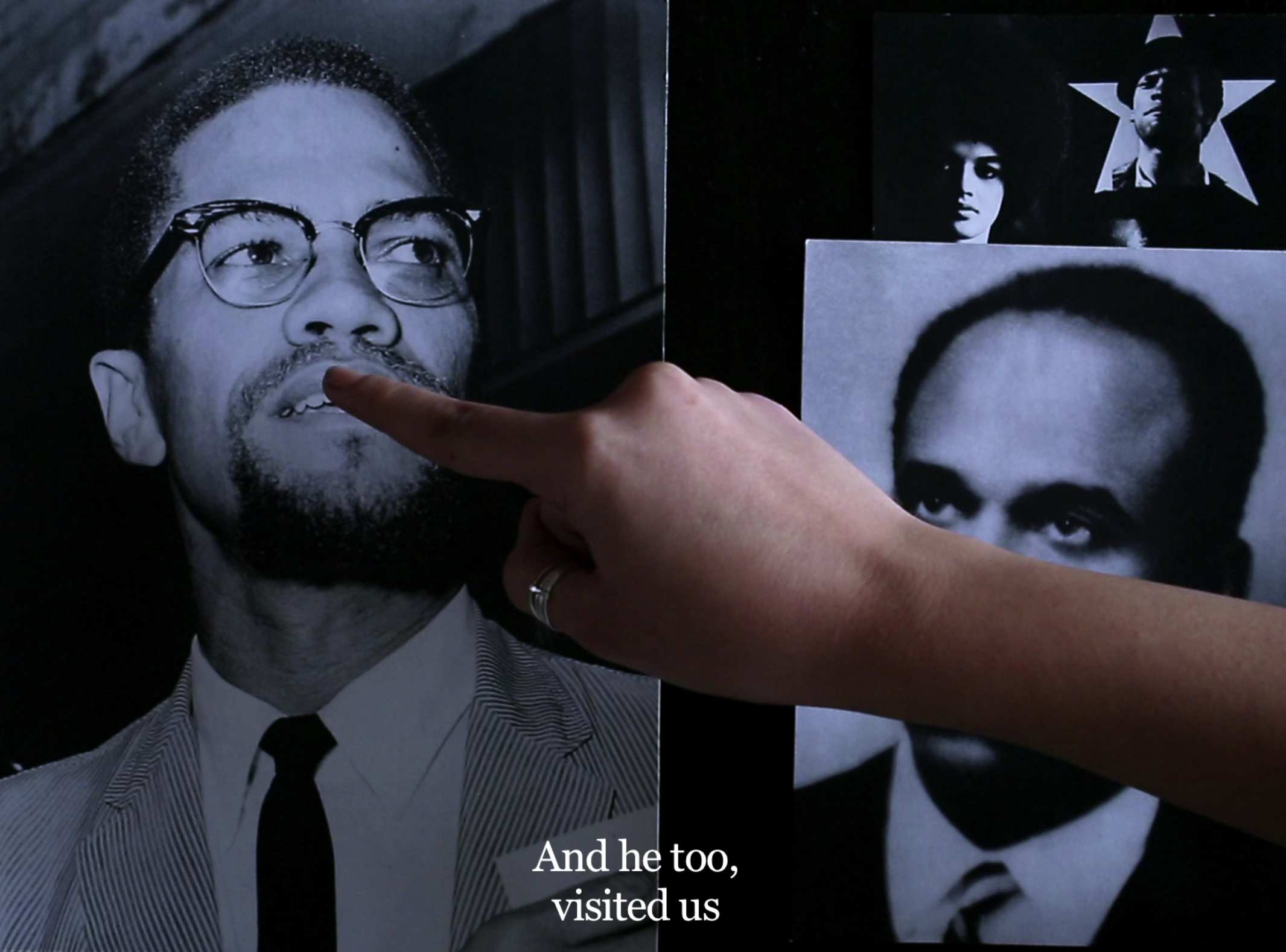

On the walls leading to another section of the exhibition are photographs of vacant spaces. Ornate dining halls with luxurious carpets and meeting rooms that seem as if they have been empty for years stare ominously out at audiences, leading them around the corner to another gallery with a single screen projecting a video onto a wall. Unlike The Mapping Journey Project, there are no headphones for the viewer to place over their ears; this video was not meant for such intimate viewing. The film Foreign Office is set in one city: Algiers. This document is a reflection on the Algerian capital’s first decade of independence after French rule between 1962 and 1972, as seen through the eyes of two young Algerians, Ines and Fadi. They, however, remain hidden throughout most of the projection. Ines says one sentence, and Fadi follows with another. Their language intermingles Arabic and French, while English subtitles linger at the bottom of the screen. The young orators – without expressing any emotions or opinions – piece together fragments of history with photographs and video clips, narrating the story of a city that was once the epicentre of anti-colonial movements.

On the opposite wall are additional photographs that build upon the narrative of those in the hallway. The locations here do not look as luxurious. There are abandoned parks and children’s slides with vegetation on them; all life has been sucked out of these vapid spaces. The images show the various contact points of the radical groups documented in the aforementioned video, such as the Black Panthers, the African National Congress, and the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine, the only one still active in Algiers being the latter. There is also a solitary silkscreen print hanging alone on a vacant wall, Archipelago, which consists of a cluster of islands formed out of the buildings referred to in Foreign Office.

A still from Foreign Office (courtesy Lisson Gallery)

Khalili, all the while, manages to speak volumes while saying very little. Through the rawness and sincerity of her work, she reveals personal insights into the lives of those who are often forgotten. Rather than speaking for her subjects, Khalili provides them with a platform to speak for themselves. In a talk at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 2016, Khalili explained that, ‘Every single life deserves to be told, because they are all singular; and because they are singular, they are universal’.

Bouchra Khalili’s untitled solo exhibition runs through March 18, 2017 at London’s Lisson Gallery.

Cover image: Fig. 1 (detail; from the Constellation Series; courtesy Lisson Gallery).