Sayed Kashua - the man who writes in Hebrew, lives in the US, and will ‘always be an Arab’

‘Last night was terrible’, he told me, shaking his salt-and-pepper head. ‘I don’t know what happened.’

Sayed Kashua and I sat on low, boxy couches in the foyer of New York University’s Gallatin School, and from the way he squinted in the morning sunshine, I wondered if he was having one of his famous hangovers. Later, he grinned as he recalled his only DUI incident – ‘My lawyer said it was a disgrace to the Israeli law enforcement that I’d gone so long without being arrested!’ – but for the time being, we were sitting in a pre-coffee haze and discussing his book tour.

‘Why do you think it was terrible?’ I prodded, running over the memory of Kashua’s lecture the previous evening. Granted, his presentation had meandered, lingering on themes of regret. He’d fidgeted under the hot glare of the stage light, removing his jacket partway through and often pausing to hunch, ponderously, over the podium. ‘I am very frustrated’, he said within the first minutes of the talk. ‘I worry I’ve made all the wrong decisions in my life’. Later, during the Q&A session, Kashua’s replies were inconclusive, if authentic. ‘I don’t know’ was more than once his answer; yet, the 100 or so guests gathered in the Manhattan lecture hall had appeared charmed by Kashua, answering his anecdotes with nods, chuckles, and applause. Afterwards, I watched as half-a-dozen tweedy literati followed him towards the door, boxing him in with their effusive, liberal zeal. From across the room, I could sense his exhaustion.

Sayed Kashua (courtesy Karl Gabor)

Kashua levelled his large eyes on mine, the morning sun glowing on his back. He shook his head again. ‘I don’t know … I just … wasn’t focused.’

Kashua has a lot on his mind these days. A little over a year ago, Kashua and his family of five relocated from Jerusalem to Illinois in the wake of violent unrest in the summer of 2014. Though he’d lived in Israel his entire life, when the ‘Death to Arabs’ marches invaded his neighbourhood streets, ‘something in [him] broke’. As tensions mounted in the holy city, Kashua and his family landed at Chicago’s O’Hare Airport, bound for the cornfields of Urbana, Illinois. In the past year, his family has made a new life for itself in this college town, where Kashua teaches part-time and his wife is working towards a PhD in social work. Still, it is clear that distance from Israel has not brought him peace. The previous evening, Kashua had bookended his talk with subdued laments for his former home. ‘I miss Jerusalem’, he confessed, abruptly and repeatedly. His brief talk was punctuated by laden pauses, reminiscent of his writing where so much lies between the lines. At the end of his presentation, Kashua gave a reading from his latest book, Native: Dispatches from an Israeli-Arab Life, compiling excerpts from his weekly columns in Haaretz, which, when read in sequence, serve as a chronology of one man’s growing despair.

Recently released in English after its original publication in Hebrew, Native is both more and less than what one might expect from a book ‘about’ the Arab experience in Israel. For one, it is emphatically un-polemical. ‘[In writing], I didn’t look for a thought or idea,’ Kashua said, ‘I looked for a feeling’. On the pages, readers are plunged into Kashua’s experience of Arab-Israeli life: neurotic, mundane, exasperating. The columns are short, yet never one-dimensional, inconclusive, yet almost painfully self-aware, blending brusque honesty with just enough humour to temper the author’s simmering ire.

‘How are you finding Urbana?’ I asked Kashua, the muted sound of Manhattan traffic filtering through the bright Broadway-facing windows. ‘It’s nice. It’s … flat. Very flat.’ Kashua’s eyes gravitated to the patch of carpet in front of his heavy leather shoes, but he looked at me when I spoke. His manners were kind, and I couldn’t help but imagine him with his children. I pictured a warmth exuding from his distracted face at the sight of his little boy. For the time being, though, his puckered brow suggested an unquiet interior.

It is this ‘interiority’ that makes Native so compelling. Kashua traffics in ordinary absurdities, using fantasy and humour to create lively, unsettling vignettes of Arab-Israeli life. Central to these pieces are themes of ambivalence and shame. Kashua oscillates between his desire to elude abuse by disguising his ‘Arabness’, and his reluctant sense of duty to bear the Palestinian ‘cause’. With a mixture of guilt and pragmatism, he teaches his children to suppress their Arabic at checkpoints, and later, is horrified when an Arab acquaintance overhears them speaking Hebrew. In a nation where ‘present-absentee’ is a legal designation and political parties routinely pledge to eliminate Arabic as a national language, Kashua’s essays suggest the dilemmas of the Arab-Israeli experience are, by definition, unanswerable.

Sayed Kashua in Jerusalem (courtesy Ziv Koren)

Native also addresses the stratification of race and class in Israel, where systemic poverty and disenfranchisement are common for many Arabs, as well as other minorities. Throughout the book, readers are made privy to Kashua’s fitful, love-hate regard for Ashkenazi privilege. In one wry essay, The Land of Unlimited Possibilities, Kashua writes to his family members about the Arab city of Tira and the magical properties of the Jewish side of Jerusalem: This place is different from everything we know. I still can’t get over the feeling of terror that seized me when I took my first shower here. The Jews have such strong water pressure. Scary.

Later on in our morning together, Kashua and I ordered affogato at an East Village café, where he recalled his shock upon arriving in ‘Jewish Israel’ as a 15 year-old boy from Tira. ‘I could not believe there were indoor toilets at the school!’ he told me, mimicking his eighth-grade bewilderment. ‘It was so clean!’ We shared a laugh – his a little hoarse, mine, a little forced. ‘My first friends at the school were Arabs who cleaned the toilets’, he added, after a pause.

Kashua arrived in Jerusalem as one of two Arabs selected for a pilot programme for ‘gifted minorities’ at the Israel Arts and Sciences Academy. His parents, eager to see their son escape the stagnation of their Arab town, sent their son to pursue his fortune in Jewish Israel, and refused to take him back when he called home to complain of hardships. For them, the desire to see their child succeed trumped their own political misgivings about the Zionist state – a choice Kashua later emulated with his own children, who also attended Jewish schools in Jerusalem.

The transition was a difficult one for the young author. He recalled the cloistered loneliness of his early months, when he spoke Hebrew in only broken, panicked fragments, and felt out of touch with his Jewish classmates. ‘I was completely ignorant of so much of Western culture’, he told me. ‘I didn’t know who the Beatles were!’ I then asked him what he made of the conflation of the terms ‘Western’ and ‘Jewish’. ‘Western and Ashkenazi, more precisely’, he clarified after a pause. And for Kashua, it was plain to see that Ashkenazi culture was regarded as the highest stratum of Israeli society. ‘I’m afraid I internalised a lot of shame. Arab culture was considered primitive, so I tried hard to cover up my Arabness.’

In Native, readers are given a visceral experience of an adult Kashua still caught by conflicting aspirations. When he moves his family to an upper-middle-class Jewish building in West Jerusalem, he reveals a lingering anxiety about his Hebrew. He frets over his diction, entertaining the futile hope that a perfect accent will gain his family acceptance from their new neighbours. Perhaps, he fantasises, his neighbours will mistake them for being ‘Druze or Circassian and not really and truly Arabs’. This intense self-scrutiny is ubiquitous throughout the book, as Kashua tries – and inevitably fails – to avoid ‘detection’: an impulse that appears paranoid and appropriate in turn. ‘They always know I’m Arab, even before I open my mouth’, he said with an exasperated chuckle, shrugging aggressively as we strode through Washington Square Park. ‘I don’t know how they do it. How do they always know?’

‘How do they always know?’ Sayed Kashua on the roof of his house in Tira, Jerusalem (courtesy Nati Shohat/Flash90)

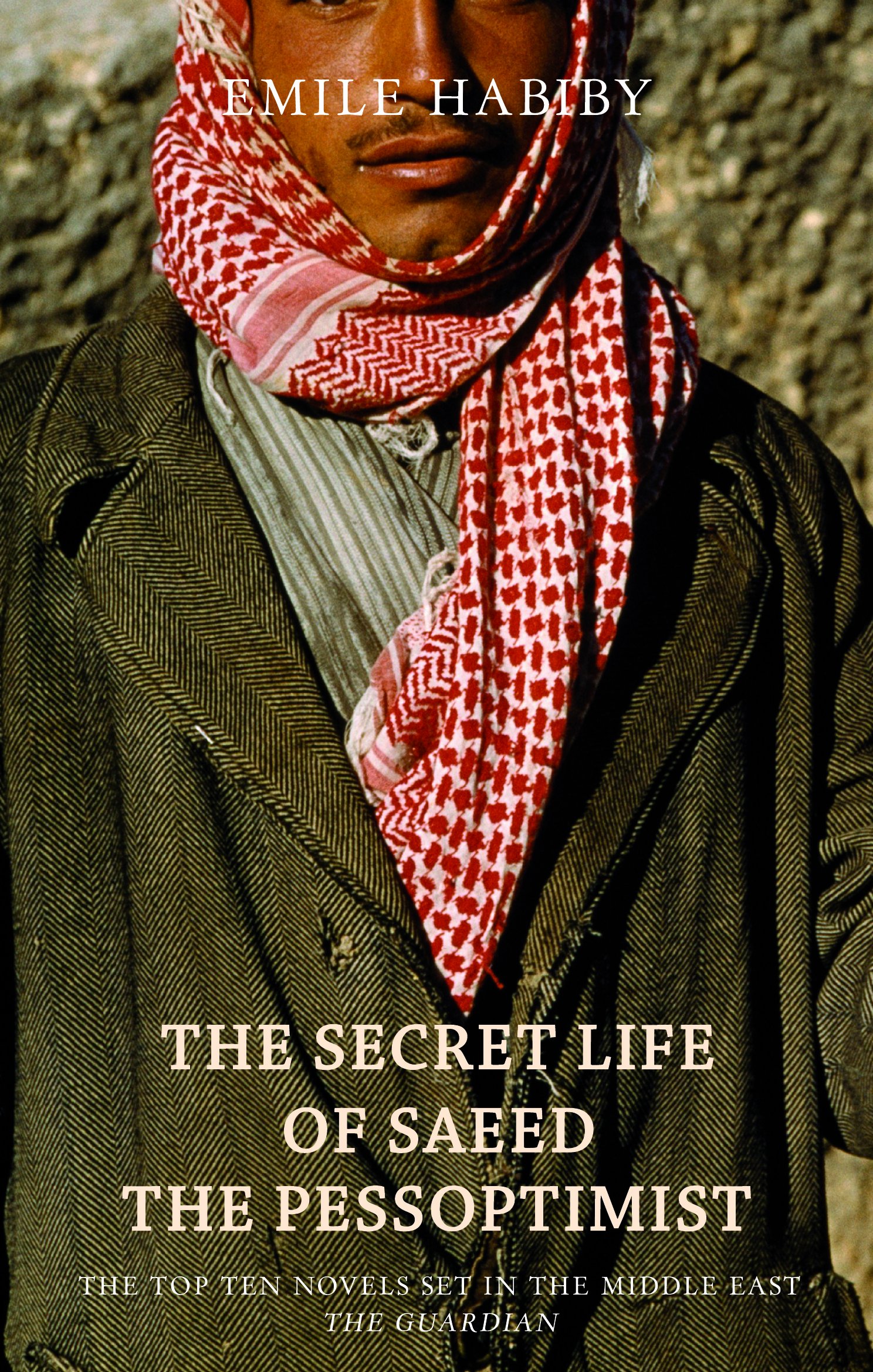

During our conversation, Kashua and I connected over a shared love for Arab-Israeli writer Emile Habiby. Habiby, writing in the 70s, addressed the contradictions of Palestinian life within the Zionist state. In his novel The Secret Life of Saeed the Pessoptomist, Habiby likened himself to a donkey, implicating Israel for its dehumanising treatment of Arabs, and himself, for playing the fool according to the Zionist script. He survived by reducing himself to a benign, braying animal, and is left wondering if the life of an ass, even, is worth saving. ‘Yes, yes, that was a very important book to me’, Kashua said, slowly smiling at the allusion. He’d met Habiby as a young boy, and called him one of his ‘heroes’. But Habiby probably had it easier, Kashua speculated; after all, he wrote in Arabic.

For a community that feels largely besieged and often invisible, Kashua’s tendencies towards self-deprecation and metaphor are unsatisfying, and even enraging

Kashua’s choice to write exclusively in Hebrew is a rare and contentious one amongst Arab intellectuals. For Kashua, the main reason is a practical one: he was raised in Hebrew schools and taught the Hebrew canon, and as such, uses Hebrew to tell his stories. He understands that this is seen by some as a cultural betrayal, but also resists the impulse of some nationalists to create a world apart from Jewish-Israeli culture. ‘Yes, Hebrew, the language of the oppressor, of the Zionist state’, he acknowledged. ‘But which language do you use to criticise a culture? The language of the outsider, or the language of the majority?’

The cover of an English translation of Emile Habiby’s The Secret Life of Saeed the Pessoptimist

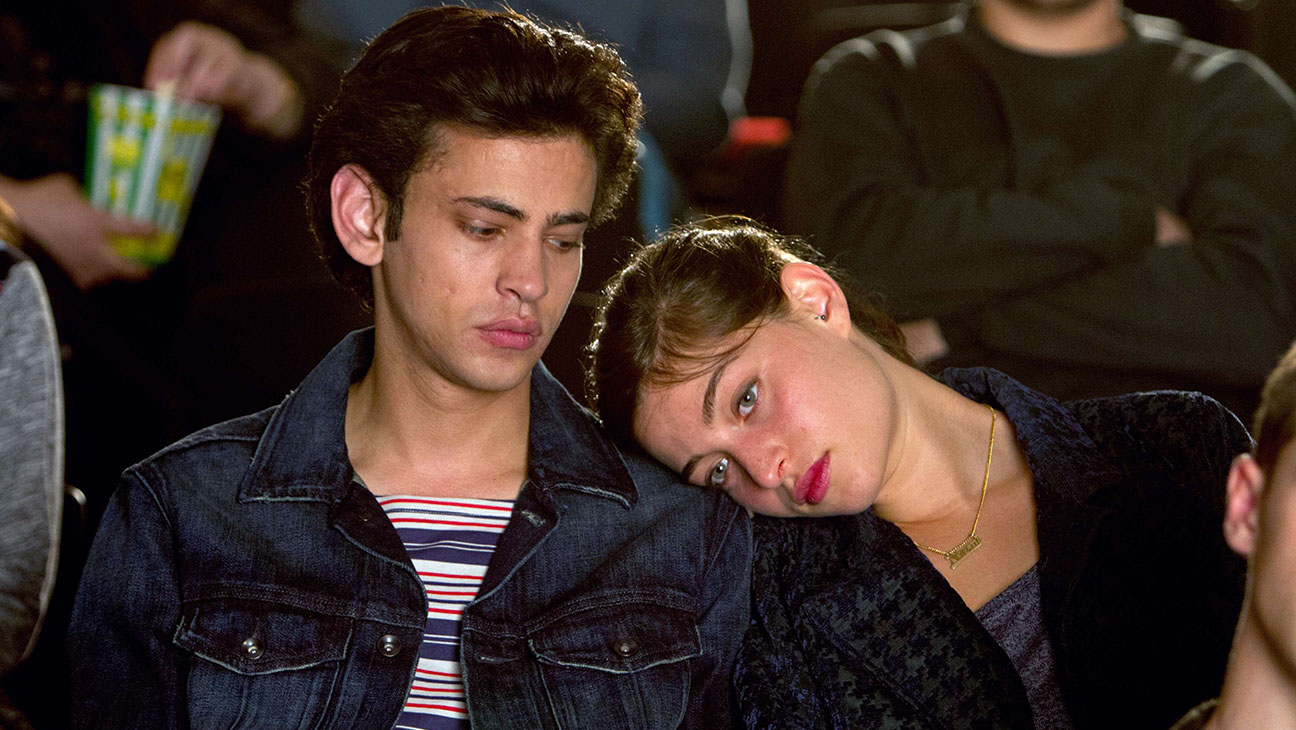

Kashua has maintained a tentative embrace with Hebrew throughout his career, publishing several novels in the language and maintaining an active Hebrew-language blog on Haaretz. When he was approached in 2004 by Israeli producer Danny Paran, who was looking to commission a television show, the prospect of writing a primetime, commercial programme came as a shock. Kashua hoped that portraying Arabs on national television would allow Israeli audiences to meet Arabs ‘who weren’t terrorists or criminals’. Paran and Kashua together produced five seasons of Arab Labor [sic.], a sitcom featuring a mix of Arabic and Hebrew that portrayed an Arab-Israeli’s frustrated attempts to transcend discrimination. The show, said Kashua, while not perfect, ‘let Israelis meet human Arabs’. Evidently, the author sees humour as an important and disarming tool: ‘Maybe if we laugh together, you’ll listen to my sad story next’.

To his critics, Kashua’s approach is misguided. He uses words that many Arabs don’t like hearing from the mouth of their own: ‘fear’, ‘regret’, ‘shame’. For a community that feels largely besieged and often invisible, Kashua’s tendencies towards self-deprecation and metaphor are unsatisfying, and even enraging. ‘It’s almost impossible to be a critic within your own community’, he reflected, hunching his shoulders again. ‘Any critique is seen as an attack on our collective honour’. And, to make matters worse, he describes amicable relationships with Jewish counterparts – something that some Jewish and Arab-Israeli readers alike have found hard to digest.

The cast of Arab Labor (courtesy Avoda Aravit)

In his essay Vox Populi, Kashua satirises his would-be political guides. A concerned Palestinian reader, Bassam, telephones Kashua to chide him for wasting his ‘platform’ on personal stories and ‘nonsense’. The young caller proceeds to supply him with a list of appropriate and ‘important’ topics, urging him to be more polemical. ‘Please write that Israel and America allow themselves to be the world’s policeman’, he requests. Kashua, with exaggerated humility, thanks the man for his instruction. ‘Tell me, Bassam, may I call you again next week?’ In another essay, Superman and Me, he portrays a Palestinian hero rendered impotent by the impossible and contradictory demands of Arab factions, the Israeli occupation, and Western pressures. Defeated before he even begins, the would-be ‘Superman’ is found begging for whisky and peanuts in an Israeli bar.

Despite his harsh appraisals of Arab dysfunction, Kashua, one could argue, does not neglect criticism of Zionist Israel. He did so from the stage at New York University, as well as during our chat the next day. ‘Let me be clear,’ he told his audience, ‘I’m in the United States now because of the political situation in Israel. Because of the racism and despair. I couldn’t handle it anymore’. Afterwards, over ice cream and espresso, he told me that ‘it’s getting worse than ever there’. From the ragged edge in his voice, it was obvious that his cynicism about Palestinian politics is more than balanced by an exasperation with the Israeli regime.

Courtesy Haaretz

In fact, Israeli liberals are perhaps Kashua’s favourite satirical objects. ‘In Arab Labor, the most racist character is an Israeli leftist’, he said, laughing. Kashua’s disenchantment with Israeli liberalism also features frequently in Native. In many of his essays, Israeli do-gooders have nothing to expect from Kashua aside from an acquiescent, assimilated Arab. In My Investment Advice, Kashua is approached by a Jewish journalist working on a ‘special programme’ for Israeli Independence Day. The conversation is mutually disappointing:

‘I really wanted to ask you how Independence Day makes you feel, as an Arab and a citizen of the country.’

‘Shit.’

‘Could you, um, maybe elaborate a bit?’

‘Yeah, sure. Independence Day makes me, as an Arab and as a citizen, feel like shit.’

Kashua is also distressed by the way political over-determinism obscures actual artistic discussion. In the essay Antihero, he parodies the assumption that his work should be seen as a stand-in for the entire Palestinian experience. When another radio host appears to be losing interest when he describes his novel in literary terms, Kashua quickly switches to deliver the expected: ‘I would say that the book is undoubtedly a rare look into the very heart of Arab society’. At this, the Jewish host breathes ‘an audible sigh of relief’. This tokenisation is shown to extend beyond Israel. Kashua, in the essay, is thrilled by an invitation to appear on a Dutch radio show alongside American author Paul Auster. Looking forward to being engaged as a novelist instead of a political object, Kashua begins to fantasise about immigrating to Holland. ‘I will integrate beautifully … [as] a highly regarded author without any connection to my origin.’ Yet, he is disappointed when the host, after a nuanced discussion of literature with Auster, turns to Kashua and asks, ‘Mr. Kashua, tell us where you were born’.

‘The question took me by surprise’, Kashua reflects:

He hadn’t asked Auster where he’d been born … The moderator insisted that I describe my childhood in the village. How hard were things there? What kind of childhood did you have? … What’s it like to be a foreign minority? I almost choked … Nothing about literature, no questions of the kind Auster had been asked … Only anthropological stuff derived from the finest colonial tradition.

Kashua’s frustration has at times turned into depression, and even despair; and in these moments, he says he can ‘understand’ why some turn to violence. At the East Village café, our conversation turned to the then-recent stabbing attacks perpetrated by Palestinian youth inside Israel. ‘I don’t think it’s really hatred’, he told me. By then, his ice cream had melted into a coagulated espresso soup, and his sticky spoon was resting against the edge of his plate. ‘I think those are acts of despair’, he continued. ‘It’s despair, despair.’ We sat in silence before he threw me another of his chopped glances. ‘People take advantage of that despair.’ Something like a spark flew with these words.

A still from Eran Riklis’ 2014 film Dancing Arabs, based on Sayed Kashua’s book of the same name (courtesy the Locarno Film Festival)

Kashua wrote of his own despair as he made a hasty retreat from Israel in 2014. When he speaks now of his decision to leave Jerusalem for Illinois, he uses words like ‘failure’; but I get the feeling that what he’s feeling is more disappointment and betrayal. After all, this is a man who, despite his caustic tone, has confessed a real and bold idealism. It was hope that first motivated him to write:

I began to write in Hebrew, believing that all I had to do to change things would be to write the other side, to tell the stories that I heard from my grandmother … I wanted to tell the Israelis a story, the Palestinian story. [I thought] surely when they read it they will understand … One day we will turn into equal citizens, almost like the Jews.

And perhaps it was this improbable hope that made the sting of 2014 so sharp. ‘[I spent] 25 years of writing and knowing bitter criticism from both sides, but last week I gave up’, he wrote in Farewell. ‘Last week something inside me broke. When Jewish youth parade through the city shouting “Death to the Arabs” … I understood that I [had] lost my little war.’ Days before their departure from Israel, Kashua found himself at the edge of his daughter’s bed, repeating the words of his father, which, decades later, resonated more deeply than ever:

I repeated to her exactly the same sentence my father said to me when he left me at the entrance to the best school in the country twenty five years ago. ‘Remember, whatever you do in life, for them you will always, but always, be an Arab.’

Courtesy Nati Shohat/Flash 90

Kashua is not sure if he’ll return to Israel. He wonders out loud whether, once his contract in Urbana is over, he’ll try to relocate to a bigger American city; after all, as he reminded me, central Illinois is ‘very flat’. The author is thinking about pursuing a graduate degree in literary theory (he says the secret to reading Lacan is to pretend he’s a comedian), but also wonders how he’ll find the time to finish his fourth novel. He is considering writing in English instead of Hebrew in the future, but says he finds the language difficult. He’s forthright about his cynicism; yet, after our time together, and through reading his books, I must conclude that his despair is not total. His prose, despite the thick overlay of sarcasm, still displays a loving commitment to his family and a defiant vibrancy. If Kashua often appears miserable, it’s perhaps due to his ideals.