Slandered and belittled, yet ever strong: female voices in Persian and Urdu poetry

The 17th century Persian princess, Zeb-un-Nissa, was a gifted poet. ‘Though I am the Leila of Persian romance, my heart loves like the ferocious Majnun’, remarked the young Sufi whilst hiding from her father, the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb, who despised poetry. ‘I want to go to the desert,’ she wrote, ‘but modesty has chained my feet. A nightingale came to the flower garden, because she was my pupil’1.

In 1681, the puritanical Aurangzeb – the last politically powerful emperor of India’s Mughal dynasty – accused Zeb-un-Nissa of conspiring with her brother to usurp his throne. Aurangzeb imprisoned her, holding the princess captive for more than 20 years until her demise, despite having later made peace with his son. ‘The imperious Mughal incarcerates the woman in the tower’, writes Lisa Sarahson, a professor focusing on early modern intellectual history at Oregon State University. ‘Could there be a clearer image of patriarchal alienation from and subjugation of the feminine?’2 While trapped in Delhi’s Salimgarh Fort, Zeb-un-Nissa continued to write poetry nevertheless. After her death, hundreds of her scattered verses were collected and published in the Divan-e Makhfi (The Invisible Collection in Persian), named after the poet’s pen name, Makhfi (‘The Hidden One’).

A portrait of Zeb-un-Nissa painted in Golconda, India, sometime between 1670 and 1700

The literary cultures of the Persianate world, like those of virtually every tradition and era, have shown the tendency to efface their female voices. These voices, however, exist, and are all the more fascinating for what they have undergone: censorship, mockery, erasure, and disregard. ‘Whether it is … the legendary Shahrzad (Scheherazade), who staved off her beheading by spinning a thousand and one tales,’ once wrote Iranian Nobel Peace Prize winner Shirin Ebadi, ‘or the feminist poets of the last century, who challenged their culture’s perception of women through verse, or lawyers like me who defend the powerless in courts – Iranian women have for centuries relied on words to transform reality’3.

While a list of Persian literary heroes would undoubtedly include Ferdowsi, Hafez, and Mowlana (Rumi), and more contemporary ones such as Ahmad Shamlou and Sohrab Sepehri, even renowned poets like Zeb-un-Nissa, Forough Farrokhzad, Rabe’eh Balkhi, and Padeshah Khatun are often regarded as afterthoughts. Worse, one might say, they were, and are often condemned for their femininity rather than celebrated for their literary achievements. In the Persian literary tradition, the poetic voices of many women have been lost, disregarded, and accused of plagiarism. Their words, in many instances, were sanitised and de-sexualised before their release to the public, and their verses have vanished in history in a way that might not have, arguably, happened to those of male writers. In the poetry of female writers such as Farrokhzad and Simin Behbahani, one can read how women nonetheless achieved authority in using narrative frames used by their male counterparts, simultaneously conforming to and breaking them to defy marginalisation and expectations of ‘angelic silence’, as writer and professor Firouzeh Dianat posits4.

In her essay, Iranian Female Authors and the Anxiety of Authorship, Dianat points to the early 19th century poet Fatemeh Baraghani – famously known as Qor’at-ol-Ayn and Tahereh (‘Balm of the Eye’ and ‘The Pure’ in Arabic). The only female disciple of Seyyed Ali Mohammad Shirazi – the founder of the new Babi faith that would pave the way for Baha’ism – Qor’at-ol-Ayn was known for her mystical and deeply religious love poems layered with metaphors, as well as her advocacy of gender equality and challenging of the status quo. ‘Now hear me!’ she wrote in one ecstatic poem; ‘since I proclaim what is manifest and true, I speak the word of victory to you. Strip off your rags of law and piety – leap naked into the sea of compassion!’5 Qor’at-ol-Ayn, who caused a stir when she famously entered a gathering of Muslim clerics sans hejab, and was an outspoken advocate of Babism, was imprisoned for four years by the Qajar government, and eventually executed as a heretic in 1852. ‘You can kill me as soon as you like, but you cannot stop the emancipation of women’, she is reported to have said to said to the reformist Prime Minister Amir Kabir, in whose house she was imprisoned before her death. During her lifetime, Qor’at-ol-Ayn’s poetry received no scholarly attention, and in 1940, one scholar accused of her being a plagiarist. In Amin Banani’s book Tahirih [sic.]: A Portrait in Poetry, one scholar notes how Qor’at-ol-Ayn was depicted by critics as a ‘saintly martyr, a cunning vixen, or a fiery feminist’6.

Forough Farrokhzad

Though literary circles have grown more diverse as access to education and publication platforms has increased, the predicament of female voices in Persian literature is far from being resolved. Farrokhzad’s feminist poetry – made even more taboo coming from a divorcée – was banned for more than a decade following the 1979 Iranian Revolution. Mina Assadi, an Iranian songwriter and poet living in exile in Sweden on account of her criticism of both the Pahlavi dynasty and the Islamic Republic, was condemned for what her detractors called ‘vulgar’ and ‘harsh’ poetry. When you were asleep, a pig pissed in the sheep’s pasture, a wolf devoured a lamb, and a fox took the raven’s hat, she wrote in one poem. When you were asleep, the dead protested injustice in cemeteries7. Assadi now works with Iranian musicians to protest the censorship of female voices in the arts.

Similarly, in Urdu, poetic female voices such as those of Zehra Nigah, Fahmidah Riaz, Parveen Shakir, Kishwar Naheed, and countless others, have been overshadowed by the likes of Mirza Ghalib, Allama Iqbal, Faiz Ahmad Faiz, and Munir Niazi. Scholars generally consider the 18th century courtesan from Hyderabad, Mah Laqa Chanda (often referred to as Mah Laqa Bai) to be the first saheb-e divan (lit. ‘author of a divan’ in Persian) poet, and the first woman whose verses were compiled and published. Much of Mah Laqa’s Persian poetry was lost, but 125 of her Urdu ghazals – written in the highly-Persianised Urdu that Dakhini Urdu was shifting towards – survive today. She was the first poet in the Deccan to recite alongside men in mosha’erehs (a sort of competition of improvised poetry in the Persianate world), and was also known for her skill with the bow and javelin. Scott Kugle of the Emory College of Arts and Sciences contends that Mah Laqa wrote her work in a male voice, and was influenced by her role as a ‘dancing female devotee of Imam Ali’8. Today, many critics recognise that she both predated Mirza Ghalib and matched his poetic skill; but most Urdu critics of the time ignored her work, in addition to condemning her for singing and dancing. In the first mention of Mah Laqa in Urdu literary criticism, only a single couplet is presented beside her biography: ‘Mah Laqa. This woman was from among the beautiful prostitutes and was a resident of Hyderabad. She was a favourite of the deceased minister of Hyderabad, Raja Chandulal. Her poetic diction was simple and straightforward’. Compared to later literary histories, Kugle writes, this was generous. It was only through the work of modern revisionist feminist scholars that Mah Laqa received serious attention.

A young Fahmida Riaz (far left, seated) with friends in Pakistan

Recent scholarly research, however, proposes that the first Urdu saheb-e divan may have actually been Hyderabad’s Lutfunissa Imtiaz, whose massive divan of 8,000 couplets was published in 1797, a year before that of Mah Laqa’s. Little else is known of Imtiaz’s life, and she most probably received less recognition for her work. Even her own husband, a notable poet, made no mention of her in his significant book on Urdu poetry.

Worse, one might say, [female Persian poets] were, and are often condemned for their femininity rather than celebrated for their literary achievements

‘The effacement of the female voice is as common as theme as the effacement of any ‘other’ in any sphere of society’, wrote the contemporary Urdu poet Zehra Nigah:

We hear many soft and mild things about feelings said by men. These expressions are so tender that I feel they must have been said by women, who spoke, but did not write their poetry. Then the men wrote down these words. Mir Taqi Mir’s daughter was also a poet, but we don’t hear about her much. Despite being the daughter of one of the greatest Urdu poets, she couldn’t be acknowledged9.

Poets of Ghalib’s calibre referred to the 18th century poet Mir Taqi Mir as Ostad, or ‘Master’ in their own poems. Known as Khoda-ye Sokhan – the ‘God of Speech’ in Persian – his pioneering works in both Urdu and Persian helped shape the poetic and highly-Persianised Urdu language; yet, his daughter is virtually unknown. Even her title, Begum Lakhnavi (‘The Lady of Lucknow’) is a placeholder: she used the Turkic honorific begum as her penname, and is thought to have been born through Mir’s second marriage in Lucknow, hence the latter portion of her title10. There is little else known about Mir’s daughter, besides a few scattered ghazals she penned – and much of what is known is mostly conjecture.

Nigah, one of the few prominent female Pakistani poets of the post-Partition 50s, notes that most of the preserved poetry of Pakistani women is attributable to either those from the higher and ruling classes, or from the Bazaar-e Hosn (lit. ‘Bazaar of Beauty’), the red light district11. The latter might explain why families were so reluctant to encourage their daughters to write poetry, as Nigah has suggested; the title of ‘courtesan’ was attached to female poets as though it were an academic title. Even after breaking ranks to sit beside Faiz and other legendary male poets, Nigah was hardly immune to the male establishment’s marginalisation of female writers. She herself recalls people worrying about how other might question the subject matter of her ghazals and make it difficult for her to find a husband. Belonging to a family with a long literary history, Nigah eventually married a man interested in Sufi poetry.

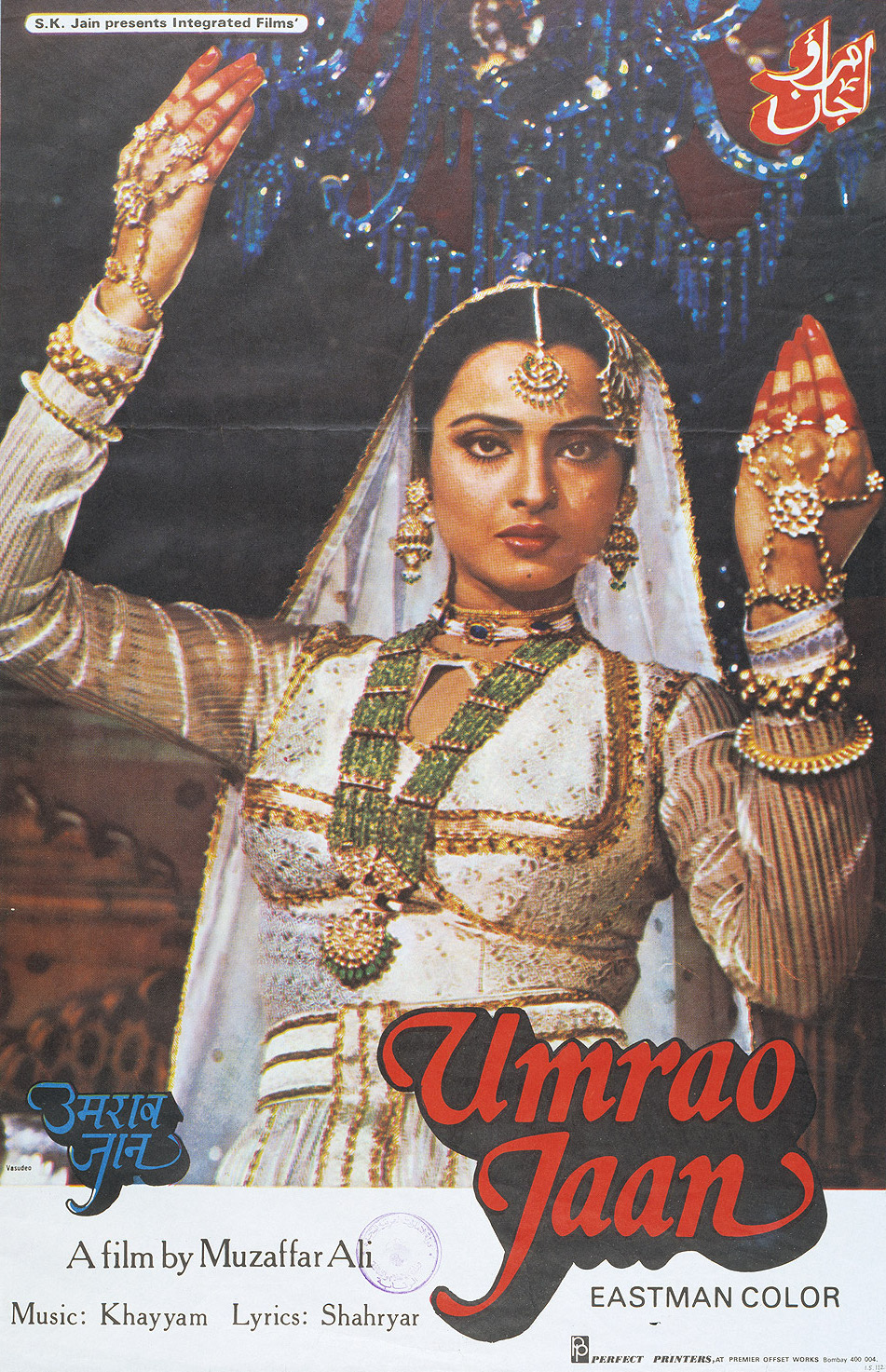

A poster for Muzaffar Ali’s 1981 film, Umrao Jaan, based on Mirza Hadi Ruswa‘s (‘Shamefaced’ in Persian) novel – known as the first in Urdu – of a cultured, poetry-reciting courtesan, and starring the legendary Rekha

Cultural anthropology and women’s studies professor Shahla Haeri researches gender dynamics in Iran, Pakistan, and India. For her book No Shame for the Sun, she interviewed six educated and professional Pakistani women, including the contemporary poet Kishwar Naheed, who had been a student of Faiz’s once and who wrote the well-known feminist poem, We Sinful Women. Naheed, who like Nigah says she was subject to abuse from her family as a result of her literary leanings and writings about men, spoke to Haeri about the humiliation she felt upon hearing men ask, ‘How could [Nigah] write [these poems]? A man must have written them for her. She is not a poet’12. Haeri lists other female poets adversely affected by patriarchy, many of whom assumed there was a male ghostwriter behind Nigah. When Ismat Chugtai published her Urdu writings in India, her audiences believed them to be the work of her brother; and, more than 35 years after the death of the renowned 20th century Persian poet Parvin E’tesami, numerous scholars still argue that her poetry was ‘too good’ to have come from such a young, shy, and ‘unglamorous’ woman.

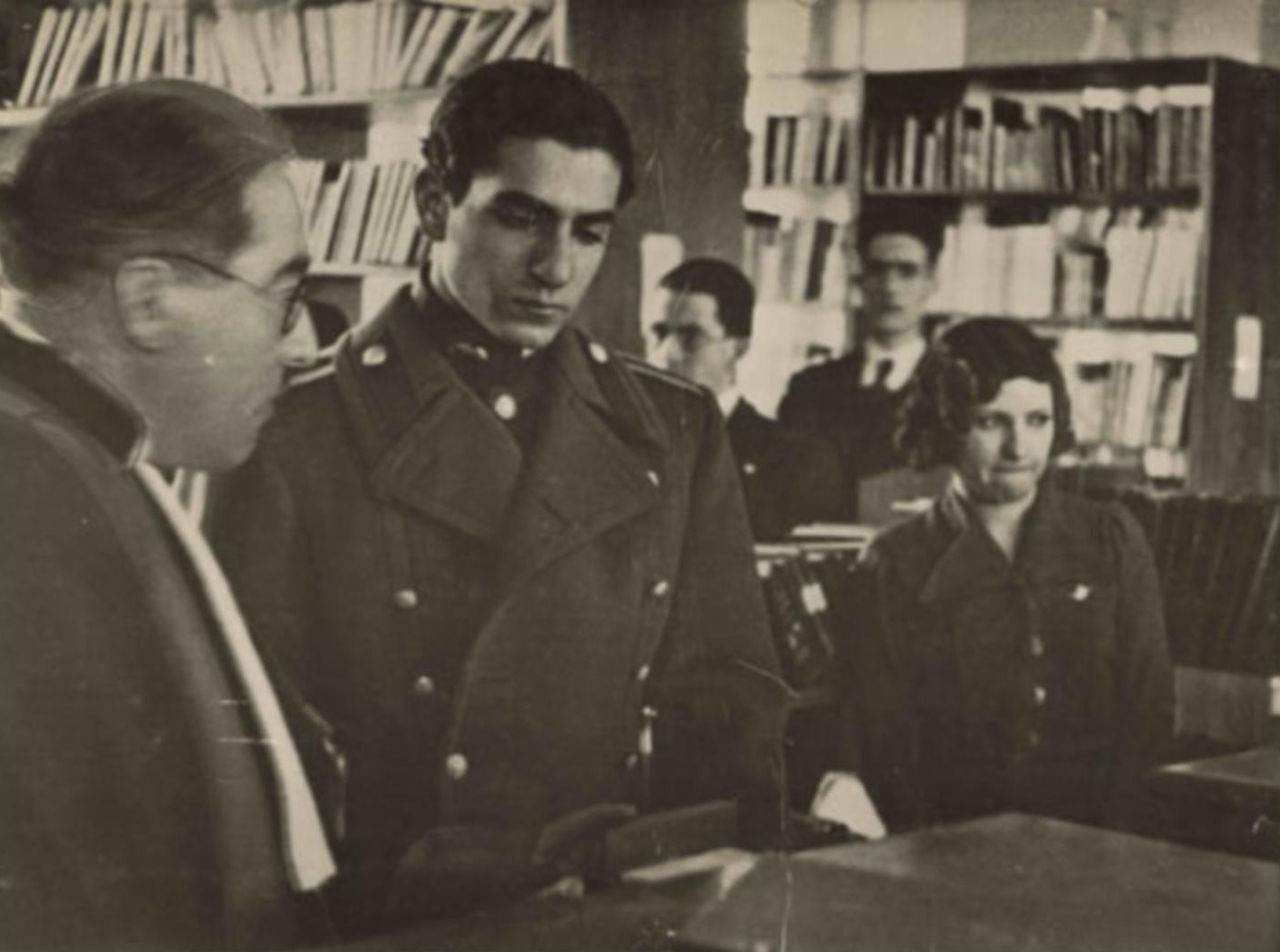

Crown Prince Mohammad Reza Pahlavi (who would become the last Shah of Iran, four years later in 1941) visiting the library of Iran’s Aali University, of which Parvin E’tesami (right) was the Head

That being said, however, only a fraction of classical Urdu poetry attributed to women was actually written by them. The term rekhti refers to classical Urdu ghazals of the rekhta (from the Persian rikhteh, meaning ‘poured’ or ‘mixed’, on the basis of its combination of Persian and Hindi), in which a typically male poet impersonates an exaggerated feminine voice, according to C.M. Naim in his essay Transvestic Words? The Rekhti in Urdu.13 Rekhti is, in a sense, transvestic literature, the feminine and idiomatic voice of which was ascribed to the domestic sphere of socially elite, secluded women during the late 18th and 19th centuries. The genre was birthed by Lucknow’s 18th century poet, Sa’adat Yar Khan, who went by the pen name Rangin (‘Colourful’ in Persian) and was reportedly based on the language of the courtesans he consorted with as a youth: hardly the upper-class society he attributed his risqué begumati zaban (‘ladies’ language’ in Urdu) to.

Rangin wrote a collection of rekhti poetry known as The Aroused Verses (Angikhteh in Persian) for the entertainment of his male patron. According to Naim, its contents dealt with ‘mundane events in the domestic life of women’ as well as ‘adulterous sex between men and women; sex between women; lustful women; quarrelsome women; jealous women; women’s superstitions and rituals; women’s exclusive bodily functions; women’s clothes and jewellery’, and more14. It was the heterosexual male’s pseudo-voyeuristic peek into the lives of secluded upper-class women and their imagined – and often, lesbian – intimacies. Men like Rangin wrote and narrated their poetry as lovers, and their beloveds – whether mortal or divine – were of ambiguous gender, although masculine ‘clues’ were aplenty. This was a facet of the Persian-style ghazal that also became popular in Urdu ones.

Women enjoying an evening concert in a Mughal miniature, painted sometime between 1650 and 1670

Carla Petievich, a professor of women’s studies and histories, calls the misogynistic rekhti genre ‘a parody of [men’s] idealised love literature’15. Rekhti became instantly popular among the almost exclusively male poets and elites of Lucknow – who enthused over male poets who sometimes dressed as women – but has been largely ignored today. The irony of rekhti is that it was purportedly narrated by women addressing one another intimately, and yet was performed by male poets for male audiences, as Petievich points out. In fact, according to her, women were only ‘quite incidental’ to this so-called ‘women’s’ poetry. Even more unfortunate, says Petievich, is that men were at least open to delve into an exclusively female world 200 years ago. Today, the male-dominated scholarly elite of Urdu poetry has condemned, to quote the author, ‘all poetic expression – of women’s experiences – real or imagined – in the feminine voice as delusional, decadent, [and/or] even evil’.

Click here to download this article’s bibliography.