How the story of a little-known dancer has inspired a new generation of Armenian artists

Born Sophia Pirboudaghian in Aran in Transcaucasia, Armen Ohanian lived a life that was both fascinating, and, for her readers, confounding. Many of the basic facts of her life are difficult to ascertain. A base and lifeless reading of life story provides clues about various love affairs with both men and women, many of whom (e.g. Anatole France) formed part of the milieu of artists and writers of 1920s Paris. Having performed throughout Europe and North America, she created a sensation with her ‘Oriental’ dances. By the end of her life, she was a prolific memoirist and translator, as well as a member of Mexico’s communist party. Few can say Armen had been given her due; but now, Lee Williams Boudakian and Kamee Abrahamian, two Armenian-Canadian artists, along with director Anoushka Ratnarajah, have shed light on the hidden history and poignant legacy of a life lived between the shadows and light of modern Armenian history.

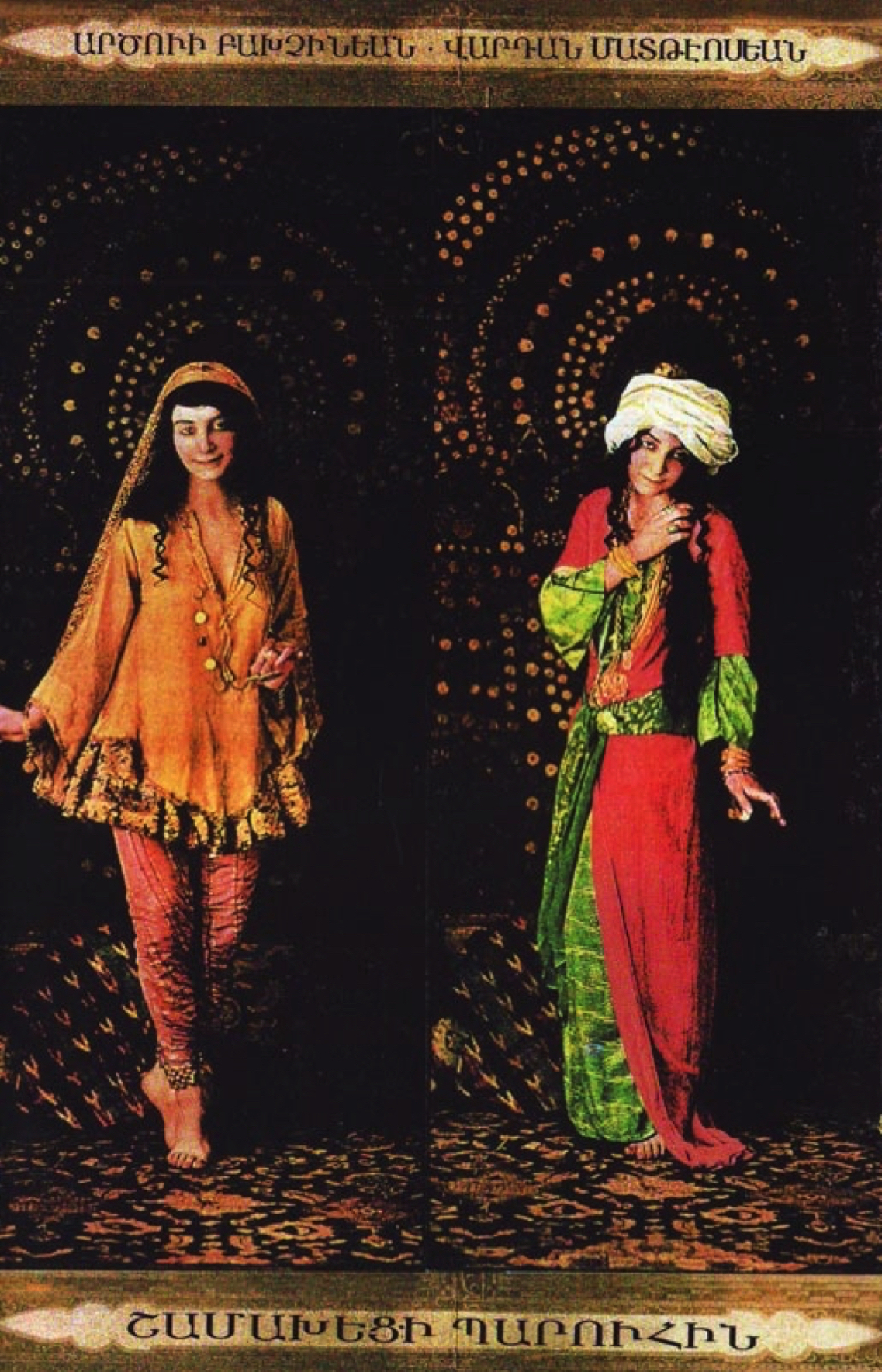

To understand Armen, they worked with her biographers and delved deeply into her first memoir, The Dancer of Shamahka [sic.] (1922). Her story – which takes places at various points in Aran and the Caucasus, Iran, Turkey, and finally, Egypt – ends as she is on the threshold of an unknown life as an artist in Europe. The twists and turns of fate in her life end as she decides, plainly against her will, to leave her beloved East. Following the pogroms in Badkubeh (Baku), Armen fled to Iran, about which she relates in her memoir a phantasmagorical set of Scheherazade-esque rites of passage that can perhaps only be understood as a shifting of light from one reality towards a more shadowy, if not unreal depiction of her inner worlds. The Persian world she describes is at times so shockingly outlandish that it might be best understood as a metaphor. To understand Armen is to understand how an artist can flourish when faced with survival; and, key to understanding this fantastical world are Armen’s own words. ‘A dancer’, she wrote, ‘is a dream'; and to preserve the dream, she felt she had to ‘show the world only her unreal self’. Armen Ohanian – whoever she was – was someone obviously steeped in Eastern and Western fantasies. She wrote with winks and nods between the lines, knew her audiences, and shifted shapes before their eyes. One can only assume she knew her readers were many, and that she understood they passed beyond her own mortality.

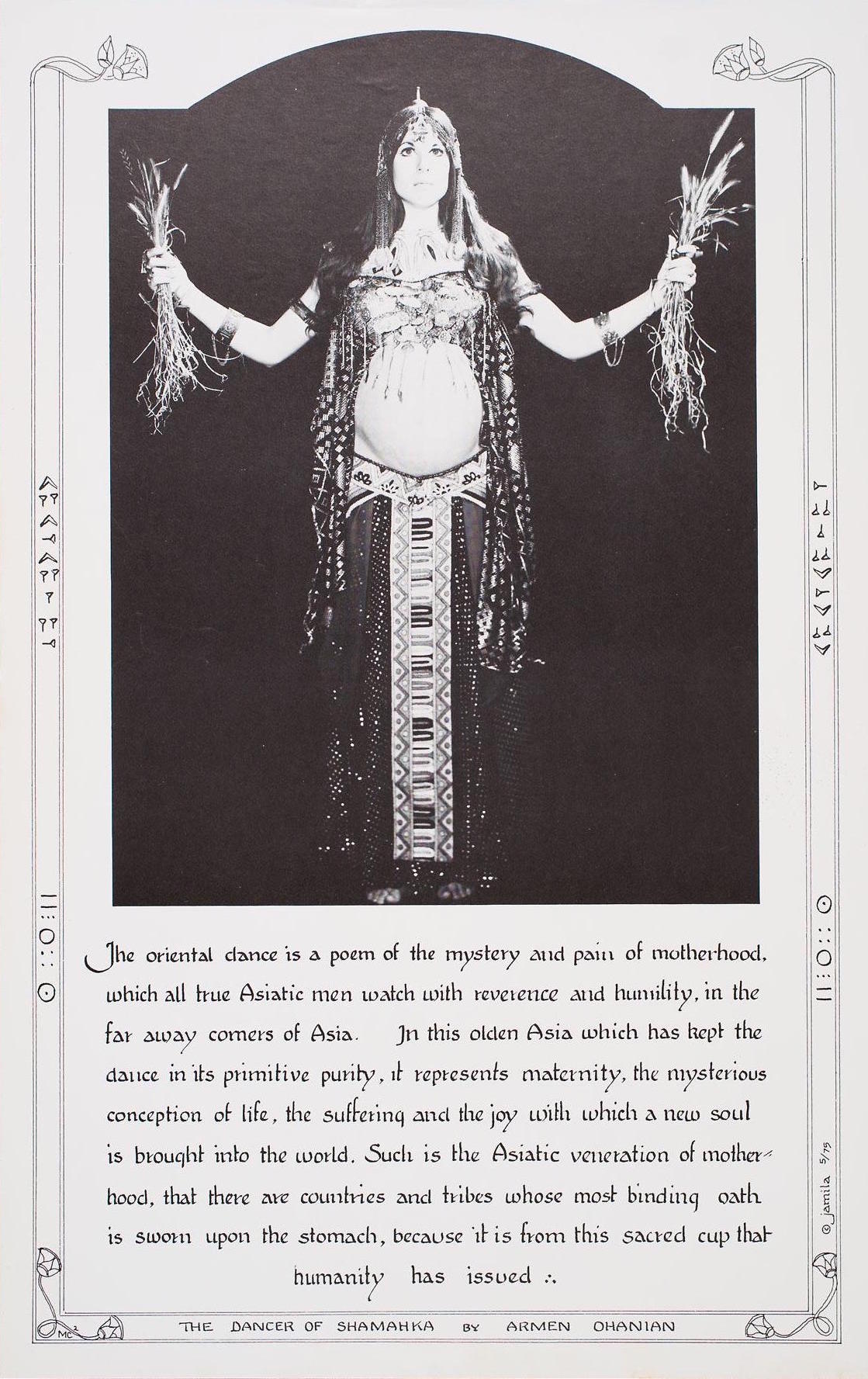

A 1975 poster featuring a passage from Armen Ohanian’s The Dancer of Shamahka (courtesy the Oakland Museum of Contemporary Art)

In her memoir, one reads of a woman who learned the passions of dance as a sacred art form, and who underwent a transformation in dancing for her survival; and so, after a lifetime of fleeing and staving off certain death, destruction, and powerlessness at the hands of men, women, and God alike, she accepted the offer to be the master of her own destiny when she signed a contract for the American and British to perform the dances of the East. ‘And for this miserable fate,’ she wrote, ‘I had for ever ceased to be [a] Khanoum (a Turkic female honorific common in Iran); I had become an artist!’

In their play, entitled Dear Armen, Boudakian and Abrahamian confront Armen and her history in a way that is equally informed and confounded by the enigmatic dancer from Shamakha. Identity, loss, and a people’s trauma that seems to transcend borders and generations carries the play to a powerful climax, in which Abrahamian performs an erotic dance and Armen is depicted as masked amidst the sensuality she created to survive. To learn about their inspiration and their own thoughts on Armen, I spoke with Lee, Kamee, and Noush (Anoushka).

In many ways, Armen was way ahead of her time. A writer once described her as ‘[having] found a way to travel between spaces and temporalities’. She’s a pretty good example of one who had what academics often call ‘intersectional identities’. What was it about Armen that drew you to her? How has her legacy managed to travel across time and space?

Noush – As a non-Western woman and an artist, [Armen] broke open so many boundaries and spaces for herself at a time and in places where barriers were significant. Queer and trans[gender] people … don’t often have access to a canon of artists the way cisgender men and white people do. Armen is yet another groundbreaking figure [who] is not only little-known [amongst] Armenians and trans/queer artists of [non-Western European origin], but who is virtually invisible within Western and Eurocentric art histories. Someone like Armen is invaluable to me as a resource and an inspiration. Her struggles with the realities of scarcity and displacement and her search for some kind of authenticity and legitimacy beyond basic survival are things I very much identify with in her narratives. Those are challenges I think artists – especially those of us marginalised in multiple ways – are always attempting to balance.

A 1918 portrait of Armen Ohanian by Émile Bernard

Lee – Over the years, the more I began to understand myself as queer and trans[gender], the more distance I felt I had to keep from the Armenian and SWANA (Southwest Asian and North African) communities I grew up in. I felt like I was always fighting to be seen, and that there was no space to be all the parts of me. I especially didn’t see how I could be both Armenian and queer, and survive in my family and cultural communities. I felt haunted by silence, and felt the absence of references, stories, and oral histories that weren’t being passed down.

This work and the stories told are not only about or for Armenians … We speak into the broader narratives of struggle and resistance that our stories are connected to and are a part of

Dear Armen was born at a time when I was determined to close that distance. I began adamantly taking up space as a person who was Armenian, queer, and trans[gender], and was searching for a community and representations of other Armenian women [who were] gender-benders and queers. Finding Armen at that time was transformative, and brought a mentor into my world. Her work was at once personal and political, speaking and moving into and through the intersections of her identities; and, ultimately, this finding of Armen was an act of community building. It brought all of us – Kamee, Haig, Anoushka, Tiffany, [and I, as well as] the countless friends, activists, and collaborators from all over the world – together. It has [also] been especially inspiring to meet and form relationships with the queer Armenian and SWANA communities who have been gathering with us and urging us to continue with our work.

Kamee – I was originally drawn to Armen because of how she created her multifarious identity; she was like a house of mirrors. My fascination grew more so after I witnessed the way in which some [people], upon discovering Armen, felt the need to possess her, to insulate her identity into a container that felt digestible only to them. I realised, then, that Armen and her legacy are symbolic of our ability to understand and be with ourselves and others in the world, [both] in history and in the now.

What are your thoughts on Armen’s experiences in times of migration and war? What aspects of her life resonated in particular with you as artists?

Kamee – The reason why a friend told me about Armen in the first place is because she knew I performed burlesque. It’s true that one of the popular facts about Armen is that she was known for the erotic elements of her dances; but, she was, of course, [about] much more than that. People today tend to focus on and highlight my dabbling as a burlesque performer – surely, because of its exotic nature – [and] everything else that I am (e.g. a producer, filmmaker, student, artist, etc.) seemingly gets thrown into the shadows. My resonance with Armen has less to do with this erotic notion, and more to do with the fact that [there was more to her], as a person and in her experiences, than just one ‘naughty’ [dimension].

An Armenian-language edition of Ohanian’s The Dancer of Shamahka (1918)

Lee – I [recently] went with my mother and grandfather to try and arrange housing for our cousins, who will soon arrive in Toronto as refugees from Aleppo. On our way to the apartment, my grandfather talked about the Aleppo he knew, decades before he fled to Beirut. While [Armen’s] stories and experiences are particular to her and her times, they are also the stories of our present. Armen’s commitment to her art, while surviving and witnessing so much [hardship], puts me in a fire to push hard in [all] this creative work we do. We are writing our her-stories. We are remembering our people. We are writing to survive; and this is where I find meaning and power.

One of the main subjects of The Dancer of Shamahka is Armen’s own gender, which she often presents in a certain light. Whether in relation to her father’s decision that she and her sisters learn to read, or her forced and hastily-arranged marriage, her gender reads as a dynamic part of her experience as an artist. How have you interpreted her writings on gender?

Lee – It took us time to put Armen on the stage as a character; we didn’t want to define her, [and] we weren’t sure how to embody her. She resists definition, intentionally masking and unmasking herself. We wanted to celebrate her fabrications of self and her-story as much as honour her truths. As a queer and trans[gender] Armenian, her gender-fabulousness endlessly fascinates me. Some days, I arrive at [a passage] and see Armen’s art and identities as screens to project my own search and questions onto. On other days, she is a humbling mirror, reflecting back truths I need to examine. In witnessing her many selves and the ‘gendered role(s)’ she moved between and through, I am inspired to keep thinking and searching for multiplicities rather than binaries, and carve out a gender identity for myself that feels authentic, and, possibly always evolves.

A 1630 map of Shamakha in the Caucasus by Engelbert Kempferin

The experience of living within the boundaries of certain norms and expectations is one that artists and writers have had to deal with for generations; artists are implicated by the market, even if they are trying to distance themselves from it. How did such norms and expectations affect Armen’s work and outlook?

Noush – In reading and interpreting Armen’s work, as with any other artist (and at least for myself), it’s important to consider the conditions under and within which the artist lived and their works were created. Armen had experienced loss on a personal and cultural level, and her own lived experiences of scarcity must have informed the ways in which she cultivated her career in order to ensure her needs for survival were met (i.e. the spiritual and emotional need to create art, to move her body and write stories, as well as feed and clothe herself). Armen certainly created and marketed her work strategically. She did what she needed in order to survive within a capitalist art market and [post-]colonial world, where narratives about the ‘Orient’ would have played an instrumental role in how her work was made and consumed.

Kamee – Noush’s response [reminds me] of how this also applies to the present. We are following Armen’s path in strategising ways to ‘sell’ our work in a ‘capitalist art market and [post-]colonial world’ because that is still our world today! I’d like to think that we’re [moving] towards a time when we won’t have to face as many challenges to tell our stories as folks who live on the fringe, or have our stories appropriated and told by others just for the sake of sprinkling a magical ‘diversity dust’ on their marketing and branding strategies.

Grigory Gagarin - Dancers of Shamakha (1847)

Lee – I remember being in college and saying in class one day, ‘I don’t care about the art market’. My teacher at the time – a long-time practising artist – turned to me and said, ‘as an artist, you have to care’ … When I look at the breadth of Armen’s work and think about the ways she choreographed, toured, wrote, published, and started her own school, I see someone to emulate, and someone I admire deeply. We can do it, too; and as Kamee said, we are doing it.

Transnational movements have occurred at high costs for Armenians. Displacement, war, and genocide have all been very real experiences. What is the role of the artist in ‘tackling’ such issues? How did Armen respond to the sufferings of the Armenian people during the 20th century through her own art and activism?

Kamee – [Sarcastically] Well, we all know that our sole responsibility as artists of Armenian descent is to create content that focuses on the genocide, and the genocide only!

Noush – What Kamee says here hits close to the heart for me, too. Do people who have survived violence – both systemic and interpersonal (the two are often entwined) – always have to write about that violence? Are we obligated to only speak to our pain? Is there nothing beyond the tragedy? It’s true that these massive acts of cultural devastation and physical and emotional violence do reverberate throughout our lives and across generations, but when and how they are [highlighted] is important. If [this violence] is all we see of ourselves, and the dominant story we tell to the world, and the only [thing] the world reflects back to us, that’s dangerous.

Unearthing Armenian skeletons in Deir ez-Zor, Syria, in 1938 (courtesy the Armenian Genocide Museum Institute)

Personally, I think artists have a role to play and fulfill in the world by telling stories, and telling the truth, as responsibly as they can. And, I also think we have a responsibility to ourselves to enjoy our work, to play, and to experiment. The beautiful thing about Dear Armen, to me, is that yes, we talk about the pogroms, but [also acknowledge that] Armen’s life was [about] so much more than that experience. And Moorkor’s life is [about] so much more than leaving Beirut, and Garo’s [than an] inherited cultural and familial trauma. The film gives every character a chance to breathe and step out of the past so they can walk alongside it, [and] clarify their relationship with it.

Lee – I find art is most impactful when it takes on the politics of the everyday, [when it] deals with the personal inside the political; I believe this is what Armen did. She spoke about and dancer her ‘Armenian-ness’, she wrote about and danced her many selves, and she also wrote about and danced the peoples of the worlds around her. She reminds me that one of the most significant [aspects] o f intersectionality is an awareness that all oppression is connected, and that there are no single-issue struggles. The sufferings of the Armenian people are connected to the sufferings of other oppressed peoples, then and now. We say ‘never again’ in our communities regarding the Genocide, but then see that ‘it’ has been happening, again and again, to so many people. This is evidence of the solidarity work that is pressing and needed. Our art is grounded in cultural specificity, yes, because that is our experience; but this work and the stories told are not only about or for Armenians. We speak of and for ourselves, but we speak into the broader narratives of struggle and resistance that our stories are connected to and are a part of.

If you could speak to Armen’s spirit, what would you say to her? How would you begin such a conversation?

Kamee – I’d probably kiss her hands, [and] then, maybe ask for her notes on my masked performance, to be honest.

Noush – I would ask her for all the hot gossip about her and Natalie Barney! And about her time in Mexico. And I [would] tell her I’d save a spot for her in the audience on our next tour … or, on stage, if she wanted to be a guest star.

Lee – Not to be trite … but I do speak with Armen’s ghost. Regularly. And the conversation often begins with ‘Dear Armen …’