Shubbak: two weeks. Every two years. Too much to see. Too little time.

Initiated in 2011 by London mayor Boris Johnson, the Shubbak festival of contemporary Arab arts and culture is the largest of its kind in the world. Embracing a wide range of mediums, from street art and underground music to dance and opera, Shubbak is a biennial festival occurring over a span of two weeks in July, across various venues in London. Although I always – for different reasons – miss the festival, I’ll do my best this year to catch the many sights and sounds of Shubbak; whether I do make it or not, though, I at least know what to expect of the 2015 edition, as a result of a chat over coffee one dreary spring afternoon in the city with the festival’s Artistic Director, Eckhard Thiemann.

I know there have been a few changes since the festival came on the scene in 2011 … for instance, the first festival received state support and funding (and was initiated by Boris Johnson), whereas the second didn’t, and neither will the third. Why is this?

The first edition in 2011 was an initiative of the Mayor of London and had HSBC as the headline sponsor at the time. The Mayor had initiated a series of cultural summers, of which Shubbak was the latest example. Originally conceived as a one-off festival, the organisers felt there was a much deeper and long-term need to engage with the region; so, Shubbak became an independent organisation, and an independent charity. We still collaborate with the Mayor’s office, but it’s an independent festival now.

A still from Michel Khleifi’s Wedding in Galilee

How else has the festival evolved? How will Shubbak 2015, for instance, be different from the 2013 edition?

First of all, it will be larger. We’ve got over 70 events in over 40 locations at the moment – a significant increase in content and volume since the last festival. This year, we also really thought about what a festival can do in London, where there’s a year-round provision of cultural events with Arab artists. So, we’ve created some very specific focuses within the festival. We have installations and exhibitions under the banner In Situ, which present Arab artists responding directly to London locations; we’ve placed a lot more works out into the public realm, into squares, into streets, on walls, and in response to London’s historic locations, like the British Museum, and the Leighton House Museum. We have asked the renowned film director, Michel Khleifi, to personally curate the major film season, and position his work alongside masterworks of Arab and European cinema history. We have a focus on London’s Arab theatre makers, showing five productions of London-based talent, and we’ve concentrated our literature programme into a very dense two-day event at the British Library.

The management of the festival is all down to you and Dan Gorman, who work on a part-time basis. How on earth do you manage to organise everything with such limited resources? Who else is helping you guys out?

We work with a really small infrastructure. We’ve got a wonderful board of directors, who help with contacts, fundraising, and advice. The execution and planning is really down to Daniel Gorman, the Festival Director, and myself. But we work, of course, in close partnership with many London organisations, and it’s that deep cooperation and partnership that makes things possible. So the Southbank Centre, Sadler’s Wells, the British Museum, the British Library and many others all help us to stage the events we programme with them. We wouldn’t be able to do it alone, and the great strength, I think, of Shubbak is that it works in such close partnership with other organisations.

eL Seed’s calligraffiti in Tunisia

You’ve got quite a bit planned for this year, in such a broad range of mediums and venues … Which events are you particularly excited about?

[Laughs] You should never ask a festival director that! I am not allowed favourites. I mentioned to you earlier some of the focuses we’re having … but I’m very pleased about the UK premieres we have of international companies and Arab artists, who will present their work for the first time in London. We’re commissioning the first UK mural from eL Seed, probably the most sought-after Arab calligraffiti artist; we’re presenting the UK premiere of Badke, a wonderful performance by 10 Palestinian dancers who collaborated with Ballet C de la B and KVS, and the performance of four scenes of the opera Cities of Salt by Zaid Jabri, which will be the first time an Arab composer will be presented at the Royal Opera House. But equally, I’m very excited about Hello Psychaleppo! – a young Syrian refugee artist, musician, and DJ who’s really made a name for himself in the Beirut underground music scene. So, we’ve got the full range, from opera to young DJs from Beirut; I think that’s what really excites me – the range and the diversity of the work.

A photograph of Jerash in Jordan, part of the Disappearing Cities of the Arab World exhibition (© Andrew Cross)

One event many people I know have been talking about is Disappearing Cities of the Arab World. What’s that all about?

This event is curated by the Mosaic Rooms, and it’s one of those events where we’ll be working very closely our partners. So, at the British Library, a number of speakers will talk about our physical and imaginary relationships with cities, and the threat of destruction to Arab cities.

Who are your main audiences? Would you say, mostly Arabs and Middle Easterners, or is there more of a mix? How have the English responded to what you’ve been doing?

We have a very diverse audience. We did some research, and at the last festival, about 29% of our audience were Arab Londoners, 29% ‘white’ London residents, and the rest was made up of the vast variety of culturally diverse audiences in London. I’m very pleased about this; it’s roughly a three-way split between an Arab audience, a white English audience, and a diverse UK audience.

A still from Sadik Kwaish Alfraji’s Ali’s Boat video installation

The response has been really positive. Many people feel it’s providing another view of contemporary Arab culture. People also commented that the breadth and variety have been such important factors of the festival. Artists have told us that London plays an important role as a home and platform for Arab artists to be shown alongside each other, with probably a greater sense of tolerance and side-by-side presence than would be possible in any other city. This kind of response makes us very proud about what we have achieved.

We’ve got the full range, from opera to young DJs from Beirut; I think that’s what really excites me – the range and the diversity of the work

Why would it not be possible in any other city?

I think the links from London into the Arab world are probably the deepest and longest globally. In Europe, for instance, cities like Paris have very close links with the Francophone North African countries, but weaker links with the [Persian] Gulf and Iraq. I feel that London really has the most wide-ranging links, and this helps with festival programming.

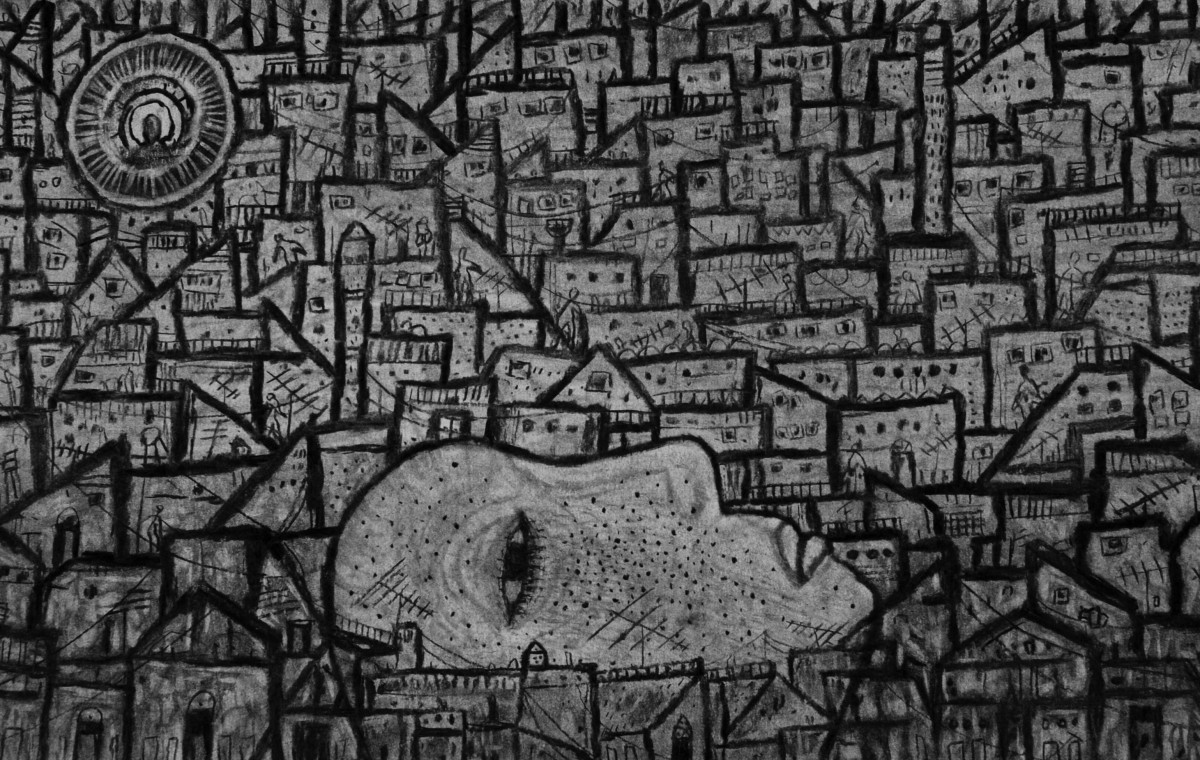

Raed Yassin - Ruins in Space (© Kalfayan Galleries)

We also have very long-established Arab communities based in London from across the Arab region. And as large parts of the region are suffering from humanitarian crises and very violent situations, it wouldn’t be possible to stage a festival of this scale in many places .In some countries – in the Gulf states, for instance – there are cultural sensitivities to certain art forms. While the visual arts sector is highly developed, it is harder to present performance – in particular, dance – compared to other forms.

How does Shubbak compare to the Nour Festival of Arts, for instance? There are quite a few similarities (e.g. the focus on the Arab world, the inclusion of so many different venues around London, the sorts of events, etc.)

I think the Nour Festival is a great festival – we speak with them very regularly, and they’re very good colleagues. The main difference, really, is that the Nour Festival is geographically limited to the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea; it doesn’t take place across London. The second difference is that it looks at culture from the wider Middle East and Muslim regions, while our focus at Shubbak is on individual Arab artists: artists with very strong visions, very strong signature styles and approaches. We cover the whole of London and we work on a much larger scale. Lastly, the Nour Festival is annual, whereas we’re biennial.

A still from Meqdad Al-Kout’s Shenab

Where does your particular interest in Arab arts and culture stem from? It’s interesting that neither you nor Dan are of Arab origin, but are nonetheless spearheading everything.

I got interested in the region just by travelling, and being inspired by the culture and the artists I met there. Professionally, it started when I was the Performing Arts Officer for the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham in 2000 and 2001. I noticed that in West London there were very large Arab, Iranian, Afghan, and Kurdish populations who were at that time very under-represented in London’s cultural offer. So I started the literature festival, Word-Wide, with a focus on Arab artists, collaborated with Saqi Books, ensured that libraries stocked books by Arab authors, and started to give public readings with Banipal (the magazine of Arabic literature in translation), which at that time only had published a few volumes.

Later on, while I was the Artistic Director of the Woking International Dance Festival, I noticed a new generation of dancers and choreographers emerging in the Arab region who were virtually unknown here in the UK, but were beginning to perform in France, Belgium, and Holland. I became very passionate to ensure that their work would also be shown to UK audiences, and organised the first platform for Arab dancers here in the UK, for the International Dance Festival in Birmingham in 2010. I later curated the Liverpool Arabic Arts Festival in 2011.

Shaweesh Bey - Al Beik, Iwo Jima

What plans do you have for the evolution and expansion of Shubbak?

I hope that after this Shubbak we will continue. Given the current difficult economic climate, it’s a challenge, but we want to continue – and will continue – and we’re looking forward to 2017. Something we would like to see is some events in-between the festival periods to keep the momentum going, as well as looking beyond London. This year, for the first time, we’re touring the dance production, Badke, to The Lowry in Manchester. Wouldn’t it be great, if in two years’ time we were able to share more of the works coming to London with wider audiences across the UK?

Shubbak: A Window on Contemporary Arab Culture runs between the 11th and 26th of July, 2015, in venues across London. For more information, visit www.shubbak.co.uk

Cover image: Raed Yassin - Family Portrait with Peacock (© Kalfayan Galleries).