A look at the Middle Eastern highlights of this year’s edition of the Frieze Art Fair

‘It’s not a trend, it’s not a passing thing’ says Rana Nasser Eddin of Beirut’s Sfeir-Semler Gallery. We chatted in the midst of on lookers with busy eyes at the tenth Frieze Art Fair (October 11 - 14) in London. It’s true that it is not a passing thing, but Middle Eastern art - from ancient to modern to contemporary - has been carrying a healthy dose of cache as big names become bigger and more expensive across auctions and fairs. Although the price tags are lagging behind their Western contemporaries by huge margins, the works of artists such as Hassan Sharif, Reza Derakhshani, Akram Zataari, and Shirin Neshat have become noticeably desirable.

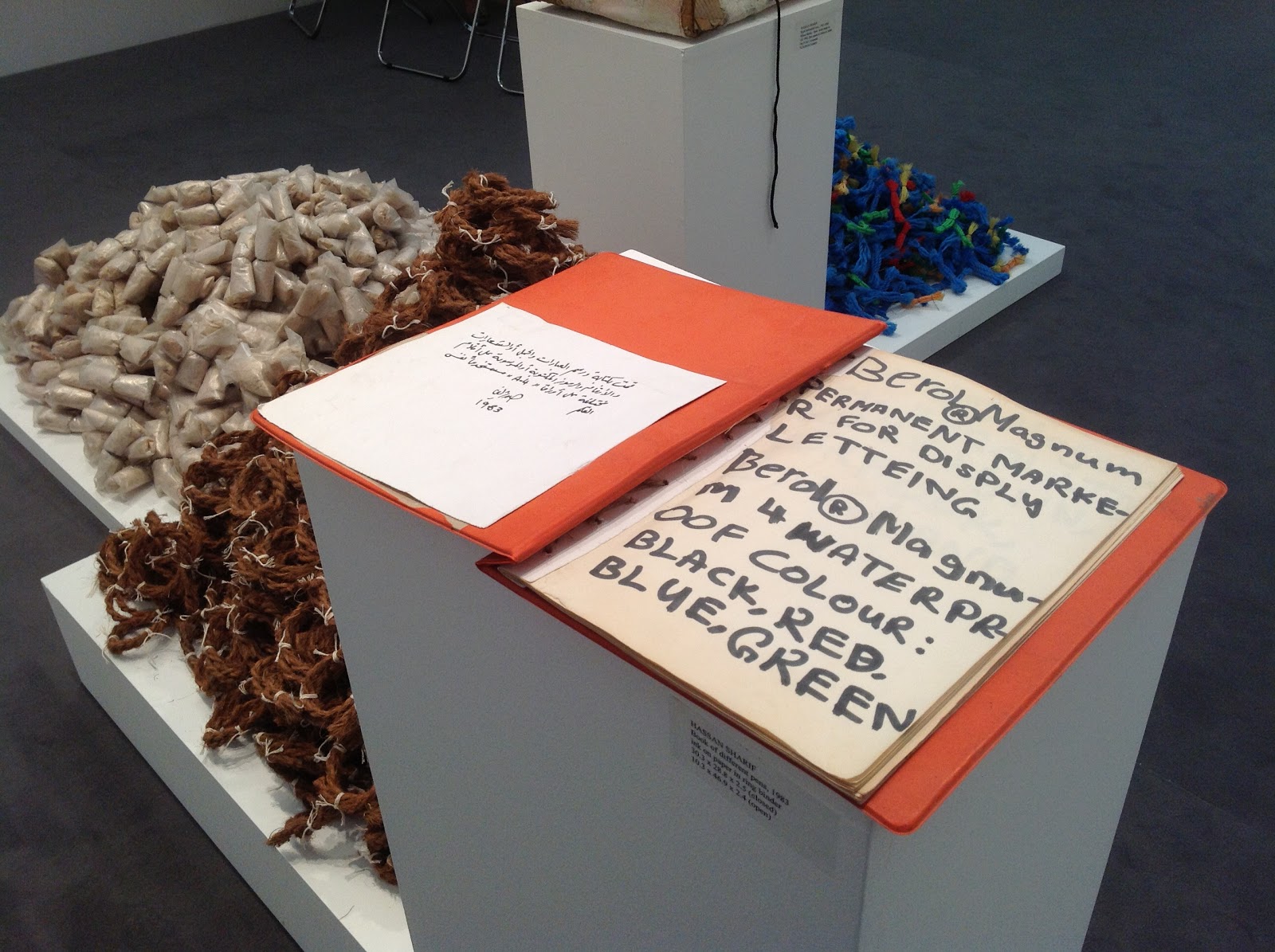

This year’s Frieze featured only a few Middle Eastern galleries, such as Dubai’s The Third Line, Istanbul’s Rampa, and Israel’s Sommers, chosen out of 500 applicants. Yet, the artists represented were more recognizable, and seem to be sticking around - at least for now. Sharif’s work is a great example of this stable foot in the canon, especially since he was spotlighted for Frieze Masters as well. Masters, a new addition to the fair, is just a few minutes away from the main venue in Regent’s Park, and you experience a warm, sobering feeling walking into it. Lit more discreetly, and coloured more quietly, over 90 galleries took part in the inaugural edition. Designed by New York-based Selldorf Architects, the high-ceiling tent they created boasted a subtle, yet distinctively more elegant aura, while still maintaining the fair-like aesthetic. While Masters brought together art from the ancient world, Mesopotamia, and the Renaissance up to the current millennia, the almost nonchalant way that they were displayed (as opposed to as grand museum gears) made them as refreshing as the contemporary works. The introduction of such masterpieces to a fair bustling with post-modern glitz was both a creative initiative, and a response to market demand, as many of the more serious collectors at the fair tend to gravitate towards modernists, enjoy investing in pieces from a range of periods, and acquire ‘safer’ names that make purchases less risky.

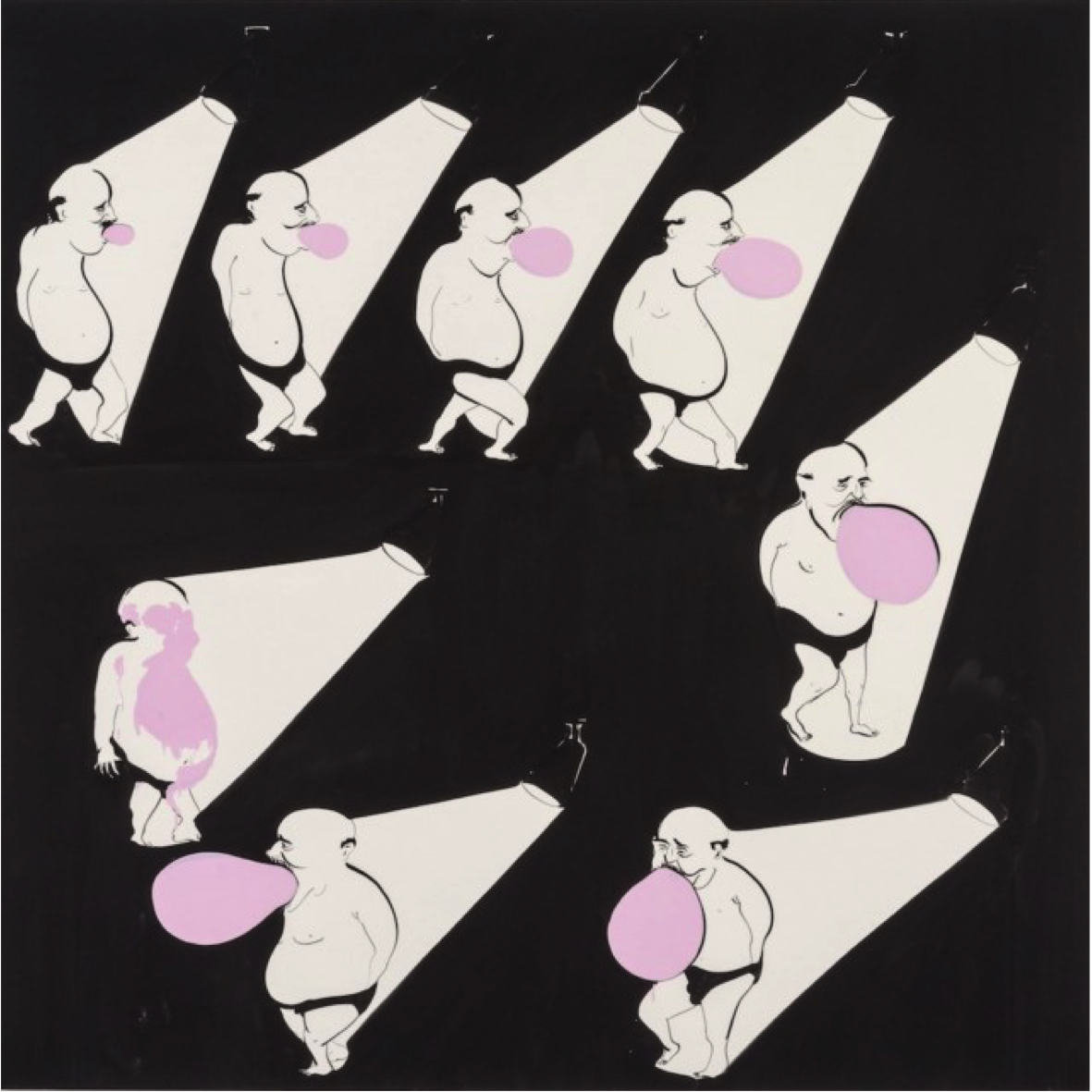

Whereas the Master’s Spotlight section focused on solo presentations, a few artists such as Sharif crossed between both the main and Masters tents. ‘He is viewed as one of the oldest conceptual artists in the Gulf, so it’s a great opportunity,’ Nasser Eddin explains. It was the sixth time that Sfeir-Semer occupied a booth in the fair, and yes - they sold. Younger galleries tend to start at Frame, and move up (or into) the main section. Rampa Gallery, which is only two-years old and showcases Turkish artists, did just that this October, and they too made a few sales. There were works by many Iranian artists – such as Tala Madani, represented by London’s Pilar Corrias - on display, although there was no official entry from the country’s lively gallery scene.

Tala Madani – The Bubble

However, it’s not just Middle Eastern artists (a category as broad and inclusive as it can be exclusive) that are holding ground in the art scene; the region’s collectors, curators and dealers are also significant. While a world economy characterised by globalisation should have brought about a worldwide recession in the past few years, certain destinations and institutions have been more or less immune. Art as a commodity is seen as worth investing in, and countries such as Turkey, as well as some Persian Gulf region nations have certainly kept the money afloat. What’s more, London’s central location is convenient for many Middle Eastern, Russian, and Chinese buyers who would otherwise travel to other art capitals such as New York. This is why many galleries – such as Pace and Skarstedt – have opened London branches to take advantage of the traffic. ‘A lot of galleries are also looking to open branches in the Middle East,’ says Rampa’s Mahtap Ozturk. During the Frieze ordeal there were synchronised, adventurous openings rippling across the city, from Tate Modern’s exquisite William Klein and Daido Moriyama exhibition to Lisson Gallery’s evening banquet with around 700 attendees.

What we might be witnessing now is an art scene becoming adept at reading Middle Eastern art, and going beyond the expected ‘Oriental’ stereotypes

But, in a quieter corner of the fair, you found Frieze Talks, which surprisingly didn’t gather a large audience, despite the relevant topics and attractive speakers. One of the talks, titled Being Difficult: A Panel on Refusal and Responsibility, raised issues of professional standards and the ethics of taking part in shows and art projects, especially in the Middle East. Vasif Kortun, curator and researcher for Istanbul’s SALT, and an influential critic, dubbed today’s art scene that of a ‘yes-generation’. While decades ago, exhibiting in shows or participating in projects would steam out a more critical approach (a ‘no’ first, and maybe a conditional ‘yes’), today there is more passivity, (i.e. a ‘yes’ followed by an occasional negotiation). Artists Hassan Khan from Cairo, and Akram Zaatari from Beirut shared the panel, while the articulate and opinionated writer, Kaelen Wilson-Goldie from Beirut chaired it.

Besides the theoretical undertones of the talk, the group highlighted the need for some sort of sign-posting or analytical look at the current art market in the Middle East. Khan argued against ‘Middle Eastern’ or ‘Arab’ tags placed on artists, and the sort of expectations that come with them. He made a poignant remark about how artists develop their own language, saying how the ‘local’ references that may be alien to outsiders are all part of the work, which - with enough conviction, and if repeated by the artist - can be decoded. He made the example of watching his first Cassavetes film, Faces, at the age of 16, and how after half an hour of struggling, he became familiar with, and was drawn into the film’s rhetoric. Similarly, what we might be witnessing now is an art scene becoming adept at reading Middle Eastern art, and going beyond the expected ‘Oriental’ stereotypes.

Hassan Sharif presented by Sfeir-Semler Gallery (courtesy Latitudes)

Perhaps there aren’t many industries as self-aware and insecure as the art industry. Reverberations of the big question – ‘But is it art?’ - jump out now and again, even from the most distinguished gallery spaces. Critics, curators, and collectors try to navigate between immediacy and longevity in an art scene where anything goes, but not everything matters, stays around, or sells more. There are constant debates about not just how to look at art, and what to look for, but also about how to value it, and what level of attention it deserves. An article in Lebanon’s Daily Star - which lamented the million dollar deals on unworthy pieces that make collecting art seem like winning trophies rather than falling in love with the piece or supporting the artist – is just one recent example.

Within this volatile scheme, such monumental fairs as Frieze, neatly categorised into Focus (a section presenting up to three galleries opened in or after 2001), Frame, and now, Masters, offer an air of certainty and vision. While for some, the addition of Masters brought a sort of conventional weight and an elitist historicity for others, it accentuated the references, and made looking at ‘old’ art more youthful. The surrealism in Giovanni Stanchi’s Anthropomorphic Figures, the conceptualism in ancient African art, and eroticism of old East Asian drawings are as riveting as ever. As the Frieze franchise expands, time will tell which trends will last, and which ones will fade out.