Stitching together sociopolitical histories of Palestine in Beirut

It was a humid May’s evening in Beirut, and the city was crackling with energy as galleries, stores, and museums staged events as part of the city’s Annual Design Week. Tucked onto a side-street, the Dar El-Nimer Centre for Arts and Culture opened its doors to host the first-ever exhibition of the newly founded Palestinian Museum, At the Seams: A Political History of Palestinian Embroidery. Outside on an overflowing patio, waiters passed around glasses of wine and one could see trays of mushakhan and kibbe piled upon each other. The crowd was a mix of the Beiruti elite, ‘artsy’ types, and foreign journalists. Some of the embroiderers were there as well, standing proudly beside their works and the videos they appeared in.

‘[In] whatever we do, whether it is historic, ethnographic, or artistic … we really need to offer the visitor something new – a new perspective on something’, said Omar al-Qattan, the Museum’s Chairman, who believes that investigating embroidery – a craft so emblematic of Palestine – and showcasing it as a living heritage is central to what the Museum is trying to accomplish. ‘If it was just an exhibition of dresses, I don’t think it would have [generated] any interest, except [amongst] those who were specialists.’ Created as a museum of the Palestinian diaspora, it was somewhat fitting that its inaugural show was a satellite one in a country with a sizeable population of Palestinian refugees. The people at the Museum are hoping that parts of the exhibition will move on to the main one in Bir Zeit in the West Bank.

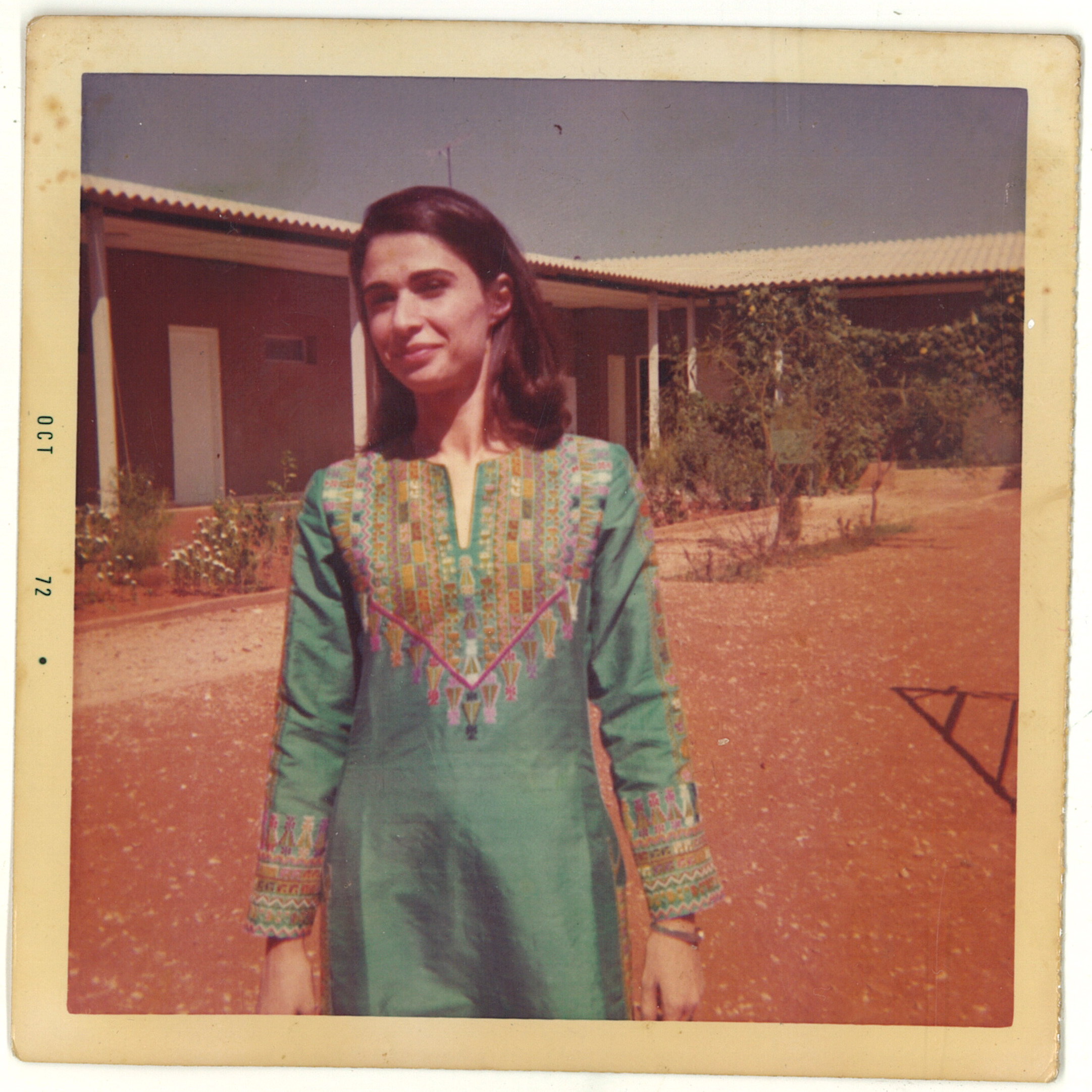

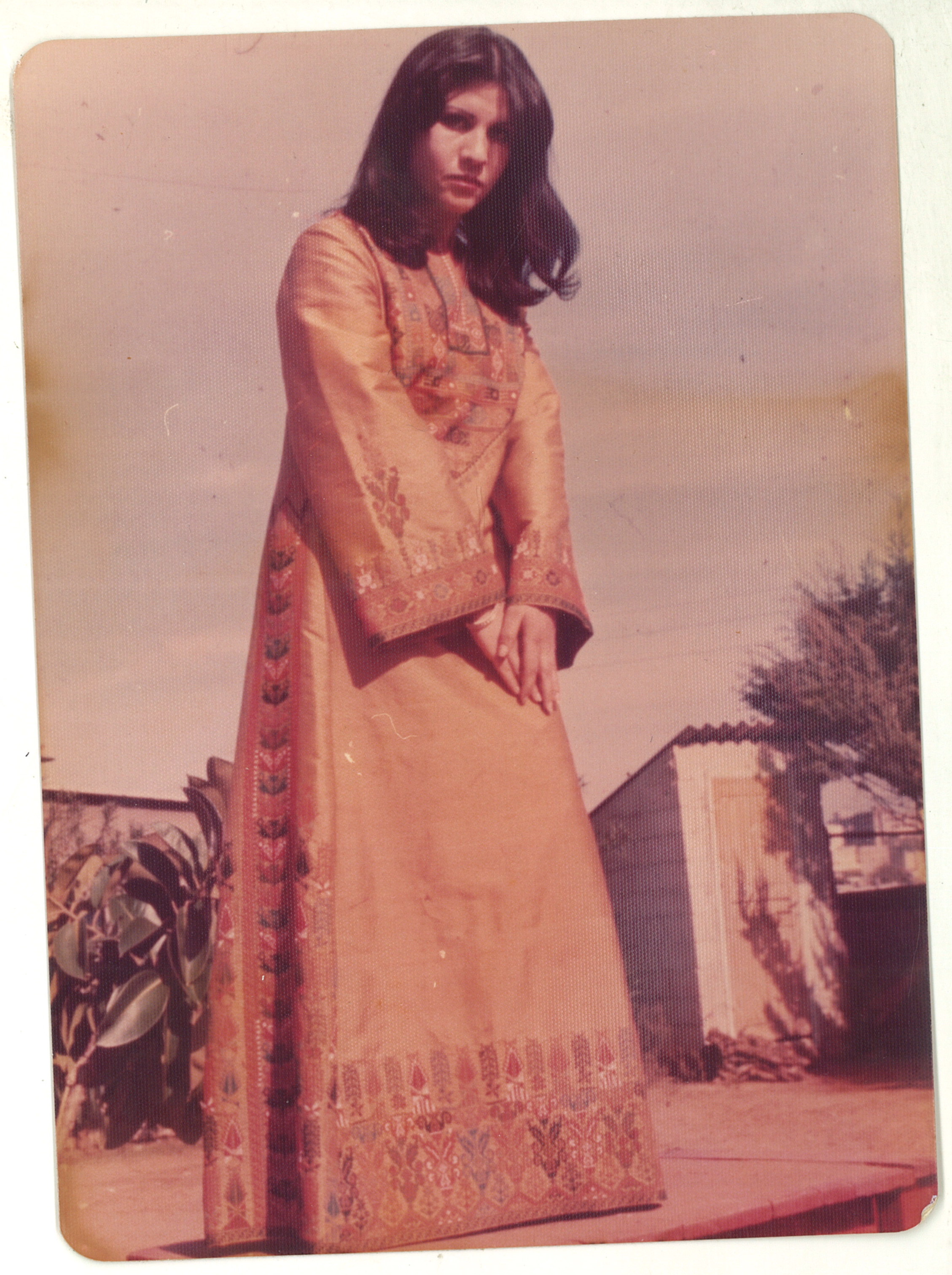

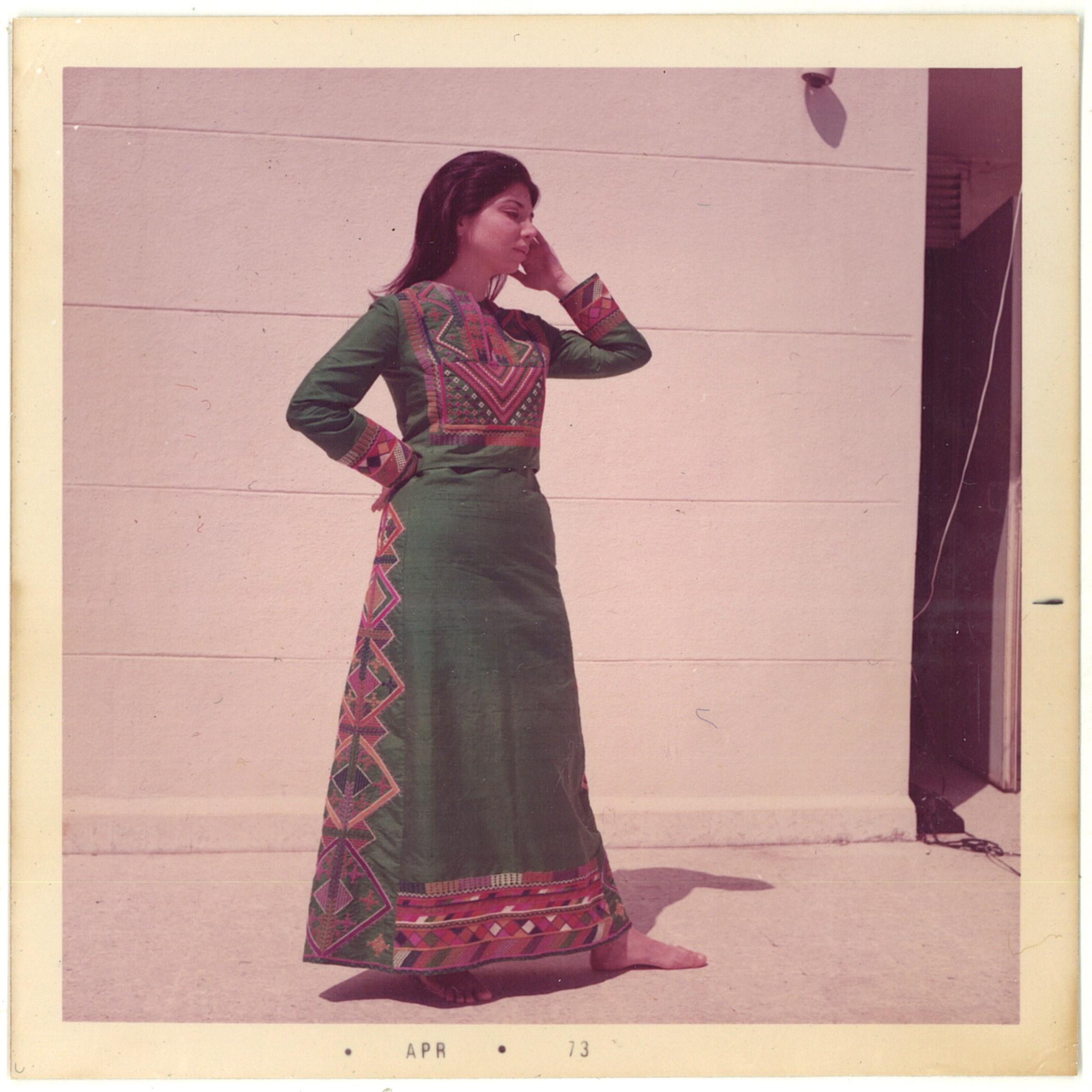

Courtesy INAASH

Before the bubbling party, curator Rachel Dedman took the press on a tour of the exhibition. Wearing an off-the-shoulder white shirt adorned with embroidery, Dedman offered her personal anecdotes on a collection she had laboured on for over two years. As she led us through the modern space, her speech became interspersed with the odd Arabic word here and there, such as ‘adi and ya’ni. When she mentioned Palestinian towns or words, she deferred to the Arabic pronunciation, saying ‘Bethl’em’ instead of ‘Bethlehem’, and th’obe instead of the elongated thobe (denoting a long robe worn throughout the Arab world). At the beginning of the exhibition, Dedman pointed out how one dress had been constructed from disparate patches of older clothes. Other dresses from the 19th and 20th centuries had stains on them where women had repetitively wiped their hands or breast-fed their children. This intimacy of the craft well lends itself to reflecting the changing conditions of Palestine.

Embroidery in Palestine was traditionally ‘something for a woman, by a woman, for herself alone, never to circulate in a marketplace’, said Dedman. ‘It was very personal, subjective, and intimate.’ In the early 20th century, it had become a language. Each town and region in Palestine had particular motifs, colours, designs, stitches, fabrics, and even styles of dress associated with them; everything from a person’s hometown to their marital status could be represented through their clothes. ‘If a woman was widowed, she would stitch blue embroidery onto her dress, or dye it a bright blue indigo; then, if she was ready for remarriage, [she would] introduce red thread again’, Dedman remarked, explaining that red – a colour typically associated with Palestinian embroidery – represented love.

A jacket from Bethlehem (photo by Tanya Traboulsi; courtesy the Palestinian Museum and the collection of Widad Kawar)

As she pointed out these first pieces, Dedman introduced a central thread running throughout the entire collection: the idea that the art of embroidery today is a way to explore and represent a diaspora. The specificity and intimacy of the craft holds a unique mirror to the shifting economic and social realities of Palestine, as curators could literally pinpoint events like the Nakba through the evolution of the craft. Moving through to the British Mandate period (1920 – 1948), Dedman showed the lining of a dress from Bethlehem, imploring us to only look at and not touch it. At that time, European fabrics – like the one used in the dress’ lining – were popular and served as statements of prestige. Such linings would often be applied to ‘eye-catching positions on the garments’ as reflections of social and economic statuses.

Similarly, as cars and buses became popular, ‘modernity began to be reflected further in the dresses themselves’, Dedman noted. As women were able to travel further than ever before, they became exposed to new motifs and designs. ‘They would meet at marketplaces and perhaps get inspiration from someone else’s dress, [and then] rush home and stitch it to a pocket, maybe forgetting something in the process and creating something entirely new.’ The macro-political event of modern transportation was thus expressed in dress: a cause-and-effect relationship between the outside world and embroidery that was touched upon again and again.

Courtesy INAASH

As we made our way past the 30s and beyond, Dedman highlighted a dress that had been purchased by Basma Kawar, a woman from Nazareth, for her honeymoon in 1921. The dress had both a French cut and motifs from Jerusalem, indicating that by this period, urban Palestinians had already begun thinking of embroidery as a rural craft that could also be used for decoration, challenging the notion that every Palestinian woman wore an embroidered dress before the Nakba in 1948.

… The art of embroidery today is a way to explore and represent a diaspora. The specificity and intimacy of the craft holds a unique mirror to the shifting economic and social realities of Palestine …

Entering the Nakba period, the tone of the collection shifted from nostalgic to sombre. From new combinations of regional motifs to a homogenisation of the thobe, the expulsion of scores of Palestinians from their homeland could quite literally be seen in the ways in which Palestinian embroidery changed. As Dedman said, being ‘suddenly divorced from the context in which they had always produced’ meant that designs, motifs, and modes of production shifted. In addition to reduced financial capabilities for some, women from regions all over Palestine began living together in the close quarters of refugee camps. ‘The geographical specificity of embroidery – where each village has quite particular motifs and traditions passed down from generation to generation, as mothers taught their daughters – then became diluted.’

Courtesy INAASH

It was at that period in Palestinian history that a central Palestinian ‘style’, which the craft is known for today, began to take shape. Flower and butterfly motifs became popular, and the cuts of dresses became uniform. As well, for those in camps without access to, or the ability to afford handmade dyes, threads, or silks, inexpensive materials began to be used. While the style is iconic on one hand, on the other, it is also a stark abandonment of the traditions of the craft, as the specificity and regionalism of motifs and stitches were so essential to its ‘language’.

In addition to this shift, the craft also came to be seen as a form of post-Nakba resistance. In the 60s and 70s, there was an effort both in the diaspora and in Palestine itself to celebrate tradition as a way to fight the Israeli occupation. Specifically, after the Six-Day War of 1967, the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO), though Samid, its economic arm, worked to revive heritage as a way of ‘countering Israeli violence, the occupation, and the appropriation of Palestinian tradition’ by founding embroidery workshops in camps across Lebanon and elsewhere in the region, Dedman explained. Women participants were told they were as important as the men fighting on the front lines, and were seen as essential elements of the Palestinian resistance.

L-R: an ‘everyday’ dress and one specific to the first Intifada (photos by Tanya Traboulsi; courtesy the Palestinian Museum and the collection of Widad Kawar)

Sharing profits as part of its pseudo-socialist structure, Samid provided employment for hundreds of thousands of women. In addition to this celebration of culture, it focused on creating wares like socks that could be worn by fighters. In the eyes of the PLO, these efforts were just as necessary as physical combat. Although not many pieces that can be pointed to as having been influenced by this policy survive today, the implications were momentous. ‘[The PLO] thought of the embroiderers … with their needles and threads as being just as important as the worker in the field, or the fighter behind his gun’, Dedman said. ‘That embroidery and labour of this kind played an active role in the Palestinian resistance is really fascinating.’

Samid’s work becomes particularly interesting when future modes of production are investigated – specifically, beginning with the time in which NGOs began to commission Palestinian women to produce pieces for international consumption. While both entities now serve to celebrate a heritage and ‘empower women’, their aims are somewhat different. These NGOs – which range from local enterprises to international organisations – commission pieces from women in camps. Although embroidery is a way for these women to remain connected to Palestine (a sentiment that was echoed by the women present in the exhibition), there are ‘ethical and political implications of turning something “uncommodifiable” into something that was sold and produced by women’, noted Dedman, who went on to say that the idea was ‘a bit problematic, because the idea that women are empowered by craft through NGOs is really complex’.

Courtesy INAASH

Although the women that Dedman interviewed found their work as positive – as it gave them independence and financial support – she also noticed how it reinforced gender roles in camp societies. Similarly disheartening, Dedman pointed out that there ‘was a noticeable gap between the amount women received for their labour and the prices [their goods] were sold for in a market’. When pressed on this issue, Dedman did not comment on ‘good’ or ‘bad’ agents, as some organisations are known to pay fair wages.

It is also worth noting that many Palestinians in Lebanon are originally from the Galilee, a region in which the craft died out early, in the 20th century. Describing this as a ‘geographic rupture’, Dedman explained that these third, fourth, and fifth generation Palestinians in Lebanon ‘embroider central Palestinian motifs that are not what their great-great-great grandmothers would have embroidered, originally’. Some of the embroiderers present at the exhibition agreed with this statement, but didn’t find it a problem that their mothers hadn’t taught them the craft. ‘I haven’t seen Palestine, my daughter hasn’t, [and] her daughter hasn’t, [either]’, said one woman who had learned embroidery in Lebanon.

Courtesy INAASH

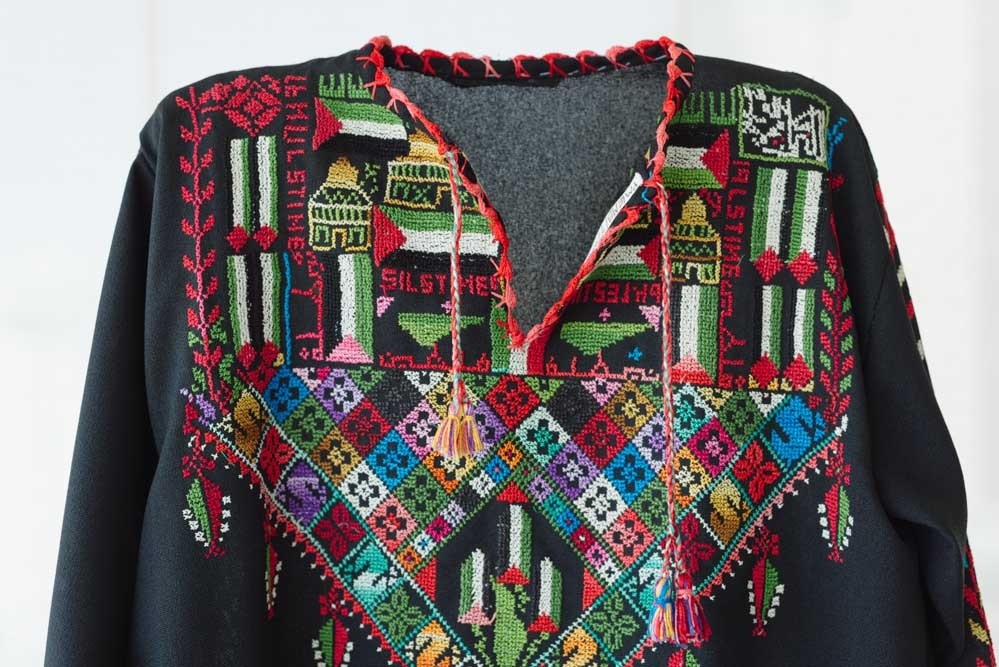

We soon arrived at a number of eye-catching Intifada dresses. Although there isn’t a clear story of how these came to be created, it is believed that the women around the villages of Hebron and the Qalandiya camp had become more involved in protests. ‘Because their husbands, brothers, and fathers were being jailed, injured, or martyred’, said Dedman, ‘they began to take a frontline role’. At the time of the first Intifada in the late 80s, Palestinian flags were being confiscated by the Israeli authorities. Accordingly, women began stitching nationalistic images (such as that of the Temple of the Mount) on their clothes. Employing traditional formats and designs, these dresses and garments were made specifically for the resistance.

Pointing out that embroidery is a time-consuming, community-oriented art, Dedman highlighted that these garments embodied the essence of the Intifada. ‘What was at the heart of Intifada was sumud, its steadfastness, its endurance. They captured the longevity and the time that are implicit and inherent in all embroidered dresses.’ This idea of the craft being politicised has continued though to today. As we reached the final part of the exhibition, we witnessed works by contemporary embroiderers, which often combined traditional motifs with explicitly political messages. In one piece, a Bethlehem-style dress by Sasha Nassar had a wall depicted on it.

A dress dating back to the first Intifada (photo by Tanya Traboulsi; courtesy the Palestinian Museum and the collection of Widad Kawar)

Part of what originally drew designer Natalie Tahhan to using embroidery motifs in her pieces is the fact that embroidery is a language. The Palestinian artist grew up wearing embroidered dresses for special events, but did not realise the history behind the designs until she was a student in London. Tahhan now takes symbols – like the kharaz (beads from Gaza) – and digitally reinterprets them before printing them onto fabrics. Although she was originally drawn to the aesthetics of embroidery, she has continued to use employ elements rooted in the tradition to educate other Palestinians who might not be aware of the history of embroidery in their culture.

‘[Embroidery] continues to feel like a resistance for those who practice it, and that was something I felt very moved and compelled by’, Dedman told me. ‘This stuff is political even when it is not being explicitly so, by virtue of being made by people – made by women – that it endures, that it continues.’

‘At the Seams: A Political History of Palestinian Embroidery’ ran between May 25, 2016 and July 30, 2016 at Dar El-Nimer in Beirut.

Cover image courtesy INAASH.