Or, Down and Out in Benghazi and Burnley: the Story of Hasan ‘the Cleaver’

In 1975, Hasan Dhaimish was fresh from his mandatory military service, like most fit, young Libyan men. He managed to complete his stint under an invisible cloak, receiving little attention from generals and corporals. ‘Dhaimish, eh? Where’ve you been hiding?’ one commented whilst he was being discharged. That same cloak would come in useful over the next few decades as he worked as an artist, concealing his identity from Gaddafi’s regime and the British Home Office – but never out of fear. Instead, Hasan turned his paintbrush into the ultimate weapon of social and political dissidence.

The socioeconomic reforms that followed the 1969 coup d’état in Libya were vehemently opposed by many. In Hasan’s home city of Benghazi, a place with an extensive history of anti-colonial rebellion, youth were tainted with a profound sense of disillusionment in the face of stagnation, prompting many to migrate abroad. After being court-martialled, Hasan chose self-exile. ‘I remember one officer asking me to join the air force,’ Hasan remembered, ‘and I agreed, knowing somehow, some way, I was going to get out of [Libya]’. Leaving the country seemed like the only viable option at the time.

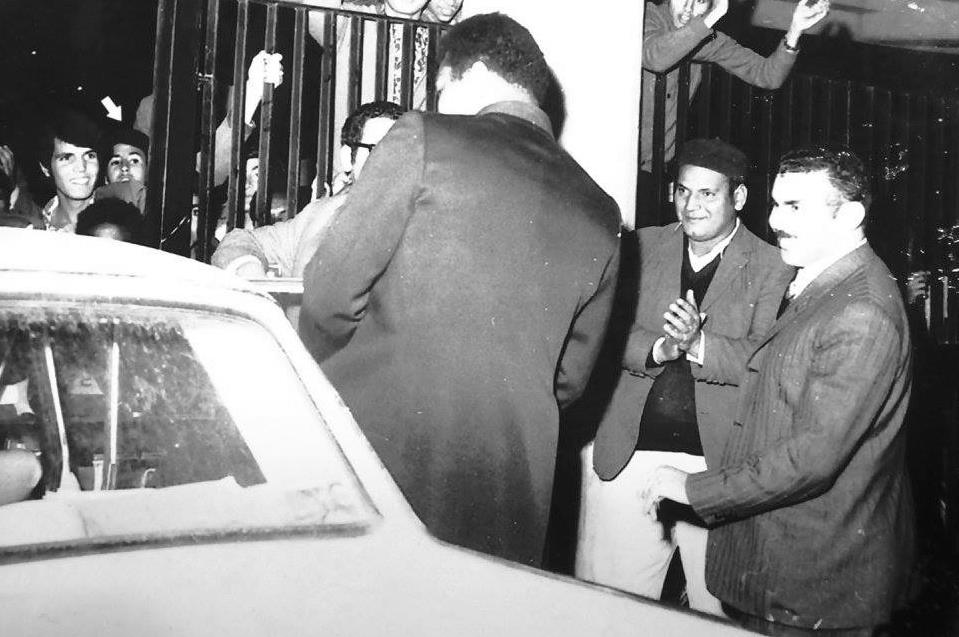

Fly like a butterfly, chop like a cleaver: Hasan (far left, beneath arrow) beholding Muhammad Ali in Libya in 1974

As a child, Hasan would watch his father, Sheikh Mahmoud Dhaimish, draw pigeons on the tiles of their home. The boy was captivated, and soon discovered his own artistic talent. ‘I remember my sister, who was also my best mate, getting engaged’, he recalled. ‘I was angry about it, so I started drawing cartoons of her on the walls of our home. I never got in trouble, though. I think my dad saw I had talent. After that, I started drawing pictures of Gaddafi in my room. Soon afterwards, my brother-in-law found them and took them to local security forces. “Are you out of your goddamn mind?” I [asked] him. I was furious, but he said they had a good laugh at them, too, so there was nothing to worry about.’

Beside a penchant for drawing and a talent for shooting hoops, music was Hasan’s passion. He would tune into shortwave radio stations to pick up the latest funk and soul from overseas and tape them on his reel-to-reel. Clad in dapper outfits consisting of flares, denim, and tailored shirts, and sporting a giant afro, he certainly looked the part. At the age of nineteen, Hasan arrived in London, with no intention of staying. Like many who left Libya in the mid-seventies, he believed Gaddafi would soon be deposed and that he would return home to the warmth of Africa. Stepping into cold England wasn’t exactly what Hasan had envisioned – but the country soon became his playground. He’d run wild at reggae festivals, Glastonbury, funk discos, and psychedelic parties like his friends, enjoying life without so much as even a pittance in his pocket. As Thatcherism was on the horizon, he’d taken up quarters in Yorkshire’s Bradford, a city that suffered greatly under the Tory Government. The Home Office was hot on Hasan’s heels, however, and he once again had to look for a way out.

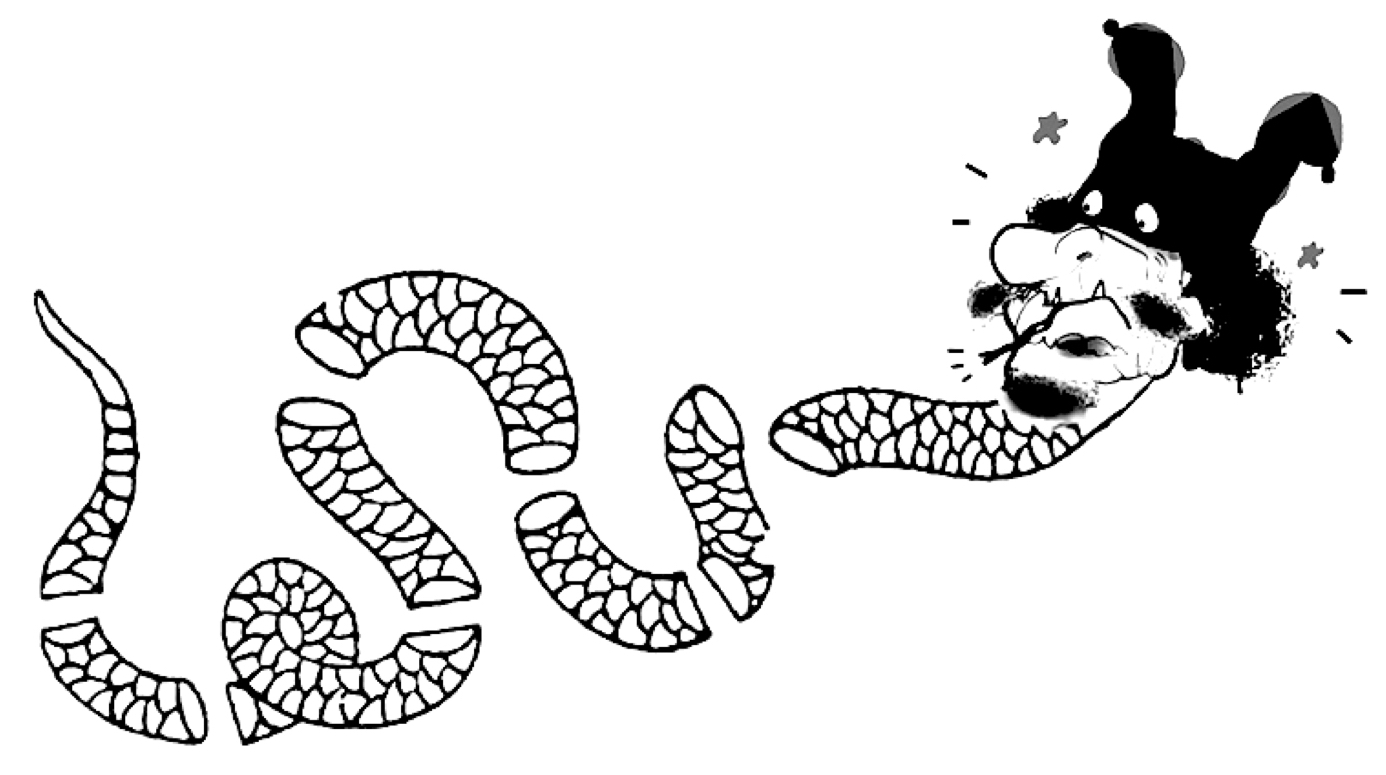

Nobody draws the Colonel: one of Hasan’s many caricatures of Colonel Gaddafi

I’ll tell you now and I’ll tell you firmly.

I don’t ever want to go to Burnley.

What they do there don’t concern me.

Why would anybody make that journey?

- John Cooper Clarke

‘I was in a café with some Libyan friends, and was introduced to a guy called Sa’ad. I asked him where he lived, and he replied, “Burrrrnley”. I’d never heard of the place, but after he assured me there was a college I could enrol in, I put my record player and rucksack in his Morris Minor. The next thing [I knew], I was in Burnley for the next thirty-five years.’

My dad never chose to integrate with the Libyan diaspora … He was an anomaly, a deviant, an eccentric. He was the buzzing fly Gaddafi had failed to swat.

Hasan had gone from Benghazi to Burnley in an odd change of place that nobody could have predicted. It was a case of life being stranger than fiction, and that also led to him meeting Karen Waddington, whom he married in 1979. ‘She’s been my rock since day one’, Hasan told me. ‘I wouldn’t have made anything of myself it weren’t for her. She stuck by me through all the turbulence.’

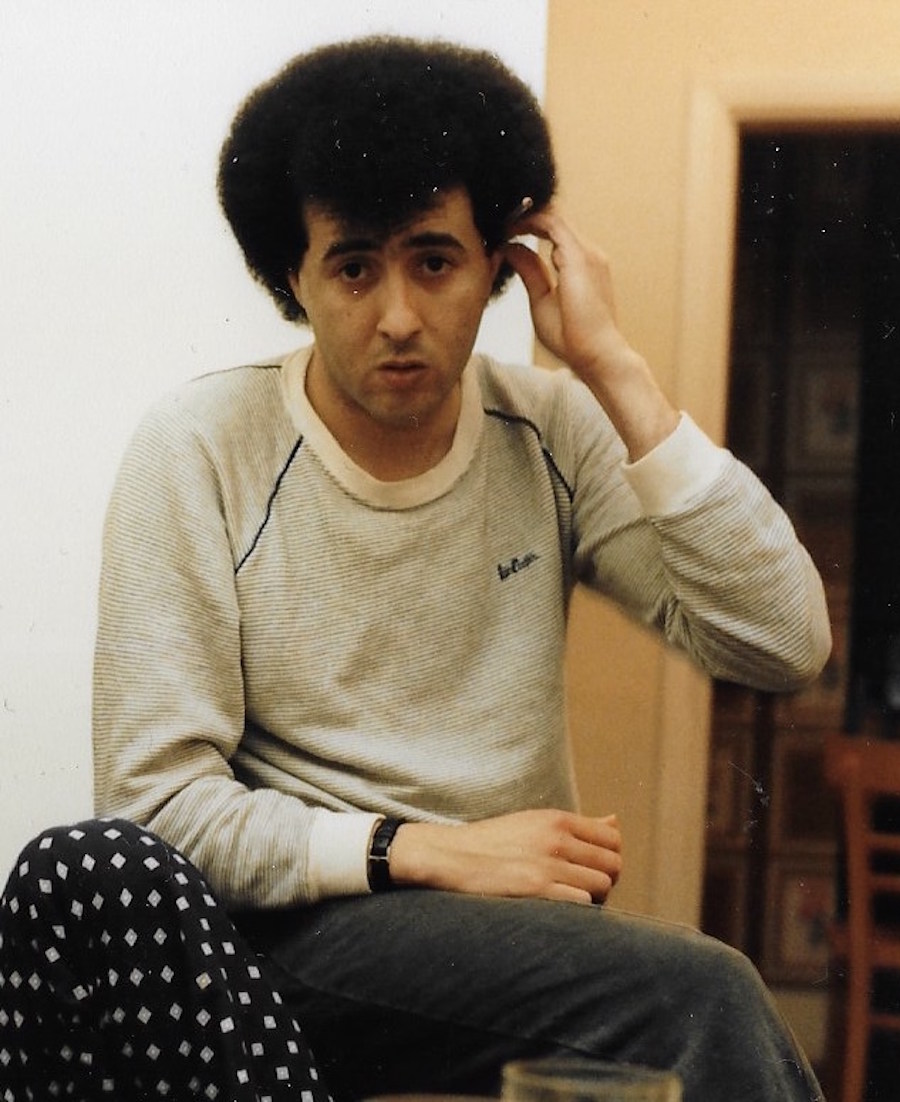

Bradford blues: Hasan, c. 1977

On a trip to London that same year, Hasan spotted an Arabic newsstand outside the Earl’s Court tube station. ‘An orange magazine caught my eye from afar, so I went over, picked it up, and realised it was for the Libyan Opposition. It was about four pages, with no contact information. I wanted to get involved with my cartoons. Luckily, the bright blue magazine next to it had exactly the same articles inside, along with contact information. I bought both, took them back to Burnley with me, and wrote to them. The only [other] contact number I had was my in-laws’.’

A couple of weeks later, his mother-in-law, Enid, arrived at the couple’s flat. ‘A Frenchman called for your and left this number’, she told him. Of course, the man wasn’t French at all: he was Libyan.

Hasan’s caricatures of Gaddafi and his associates were received with adulation from members of the Opposition, and it was then that he adopted a moniker and gave to the world ‘Alsatoor’ (‘The Cleaver’ in Arabic). The cartoons appeared in the same magazines he’d spotted in Earl’s Court, and also spread to other similar publications. As the only Libyan for miles around in Burnley, Alsatoor operated covertly and blended into his new hometown as best a foreigner could. He was well aware of the dangers his work posed for him and his family back in Libya. In the midst of 1980s, when Gaddafi’s notoriety was at its peak, anti-regime activists like Hasan were at great risk. Despite this, Hasan maintained his double-identity with an air of defiant coolness. His friends in England knew little about Alsatoor and the mischief his satire was instigating.

As an active member of the Opposition, Hasan attended rallies in cities around the UK, including the infamous one where police officer Yvonne Fletcher was shot dead outside the Libyan Embassy in London in 1984. Alsatoor persevered even after the Opposition crumbled during the following years, working to his own rhythm while also trying to make ends meet. ‘I got denied a job at the petrol station – can you believe it?’ He once asked me. ‘That was soul-destroying. I went through many jobs in Burnley, from kebab houses to nightclubs. I’ll never forget the Italian restaurant I worked in that couldn’t afford my wages. The chef gave me two sirloin steaks at the end of the night as payment. I went home singing Taj Mahal’s Satisfied ‘N Tickled Too to Karen: I’m comin’ back home with a pocket full of tens …’

In spite of the economic pressures he was under, and unfettered by life’s harsh realities, Hasan’s creativity continued to flow. When not penning political satire, he’d paint to the sounds of musicians like Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, and Dexter Gordon, or Blind Wille Johnson and Skip James, bringing jazz and the blues to life through his artwork. He swore by Paul Oliver’s The Story of the Blues, which was to many of his pieces gospel. In the meantime, British satire from Private Eye, Giles, and The Viz contributed to the development of his own unique satirical style: rhythmically witty, acerbically insightful, and playfully relentless.

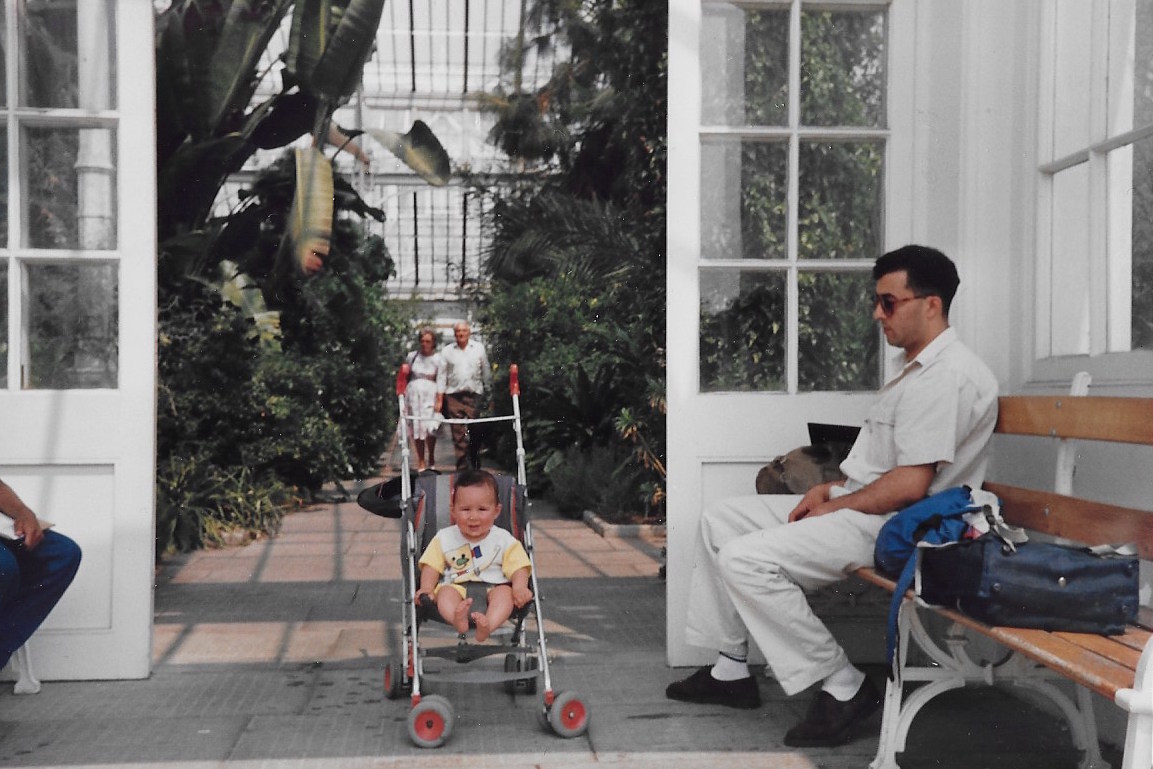

The author with his father at London’s Kew Gardens in 1989

In the nineties, Hasan trudged through his A-levels and a degree whilst waiting tables at Carlo’s restaurant in neighbouring Colne. In 1995, he began his teaching career at Nelson & Colne College’s graphics department. ‘Has’ was a popular figure there amongst students and fellow staff, known for his unorthodox approach to art and curricula. Background music never ceased to resound and turn students on to his waves of artistic experimentation. ‘You’re Hasan’s son! He’s the man!’ many people used to tell me. Still, they had no idea who Alsatoor was.

The rise of the Internet brought a pivotal turn: Alsatoor became global. After the teaching day was over, he’d glue himself to his desk watching Arabic-language news picked up from the array of sketchy satellite dishes he’d accumulated. Hasan began to manipulate screenshots and sound bites, majestically mocking Gaddafi through political satire. Stylistically, his work transformed over the decades in accordance with technology, but his staunch opposition remained unshakable until the very end.

Hasan found it hard to maintain hope and fervour for political change in Libya, particularly after the disarmament in 2003, which saw the nation momentarily return to the international community. Perhaps it was the online response that spurred him to carry on, despite the bleak realities. It wasn’t until thirty-six years after leaving Libya, however, that the fight seemed worthwhile at all. During the 2011 Revolution, he worked interminably as news came thick and fast from all directions. During February and March of that year, he sketched notes and cartoons as he received calls on his landline and mobile phones, sometimes simultaneously. Tinged with coffee and tea stains and cigarette ash, this collection epitomises Hasan’s experiences during the early stages of the Revolution. Still stashed away from the public eye, the work narrates the sporadic disjointedness of the Revolution while never reaching a conclusion.

My dad never chose to integrate with the Libyan diaspora. This wasn’t because he wasn’t sociable or felt he didn’t belong, but because he was an anomaly, a deviant, an eccentric. He was the buzzing fly Gaddafi had failed to swat. Even though Hasan had pledged to stop drawing him once his regime fell, his daily publications continued to criticise Libya’s debilitated political landscape. With the advent of social media, Hasan aroused laughter, hatred, and controversy amongst his followers. The burning zeal he had for the cause he’d fought for during his early days as an asylum seeker in England lived on, and his flame continued to burn.

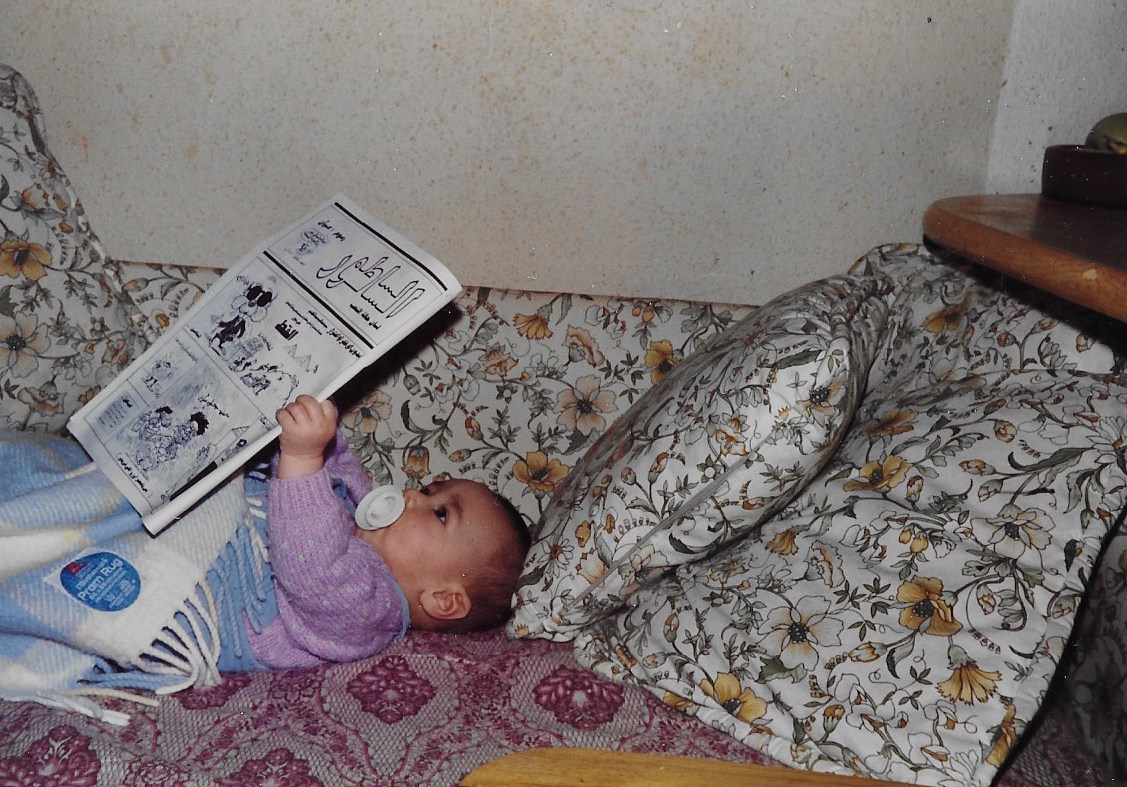

The author, aged eight months in 1988, enjoying his father’s cartoons

During his final years, my father’s artistic flair was subsumed by Libya’s poisonous political landscape. His ambition was always to promote education, creativity, and individuality amongst youth, and he fulfilled this. First and foremost, he was a teacher; he was a black sheep in all the right ways, and anyone who spent time with him became enlightened somehow, whether in their knowledge of art, music, football, or Libya. Truth be told, Alsatoor became a burden to Hasan. All Hasan wanted to do was paint under the blue skies of the Mediterranean and the grey clouds of Lancashire; but his selflessness and zeal for a free Libya were stronger than his desire to paint. But forget all that. When I step into his studio, I can still smell hash, incense, and paint, hear J.J. Cale’s lo-fi sound coming from the speakers, and see my father on the sofa, shackled to a sketchpad.

In memory of Hasan Dhaimish, a.k.a. ‘Alsatoor’ (1955 - 2016). More of Hasan’s works can be viewed on his Facebook fan page, as well as his website.