Brigands, burqas, and bushy eyebrows: Central Asia and the Caucasus in Soviet cinema

My ability to speak Russian like a native constantly brings about assumptions about my ethnic heritage, from jokes about vodka and imitations of Russian accents to comments about how I should be used to cold weather, whenever I so much as shiver. I, along with many Russian-speaking Central Asians and Caucasians (i.e. from the Caucasus) from countries belonging to the former Soviet Union, are caught in an identity limbo. How, for example, do I explain why it is that I’m more fluent in Russian than my native Juhuri, a Jewish variety of the Iranian Tati language closely related to Persian? Today, I force myself to wrap my tongue around the few Tati phrases I know, in a desperate effort to preserve what is left of my identity – an identity that is falling like sand through the spaces between my fingers. In the past two generations, my family’s heritage was subdued under Russian dominance; and now, as immigrants, we’ve had to adopt new American identities.

My inability to speak Tati isn’t merely an accident of assimilation, but a calculated victory of Soviet leadership, which aimed to replace indigenous identities with an ‘international Soviet’ one, favouring Russian culture as an elite ‘big brother to all other nations’. This international Soviet identity, in the words of Dyuyshen in the 1965 Soviet Kyrgyz film The First Teacher, was supposed to make people like me ‘fight for the global revolution’ and become a cog in the Soviet machine. While Soviet policies concerning nationality and ethnicity were complex and changed over time along with the needs of the central government, their aims were to ensure that ethnic minorities fell in line with the Soviet agenda. These policies weren’t hidden away in documents; they could be seen in Soviet society and especially the media. Films were ideal mediums through which to propagate not only communist principles, but also the government’s attitudes towards minorities – particularly those in the Caucasus and Central Asia.

A still from The First Teacher

Many of these films have now been classified into a genre of their own dealing with the aforesaid regions: the ‘Soviet eastern’ genre1. These films were well-known in their time, with Central Asia and the Caucasus often portrayed as exotic and fantastical distant lands full of mountains, deserts, and wild people. They mirrored American westerns in the sense that westerns tended to justify reasons for Euro-American control of the Western frontier from native ‘savages’, while Soviet ‘easterns’ justified Russian imperialism by portraying indigenous peoples as being in need of becoming ‘civilised’2. Only through ‘Russification’ and communism as an ideology, it was believed, could indigenous minorities in the Soviet Union reach the status and intelligence of their Slavic conquerors. This way of thinking, as well as the Soviet fascination with Central Asia and the Caucasus can be traced back to pre-Soviet Russian Saidian-Orientalist literature.

Classicist Russian writers such as Leo Tolstoy, Alexander Pushkin, Mikhail Lermontov, and Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin used these regions as settings for stories such as Prisoner of the Caucasus and A Hero of Our Time, both of which were made into films3. Saltykov-Shchedrin, best known for his satirical Tashkent Gentlemen, had never even set foot in Central Asia; according to historian Alexander Morrison of Kazakhstan’s Nazarbayev University, the writer had instead referred to previous Russian Orientalist literature dealing with the Caucasus as the basis for his ideas about the Central Asian Steppe, and as a result conflated the two disparate regions into one ‘Eastern’ monolith4.

Mirza Abolhassan Khan Ilchi of Iran and Russia’s Nikolai Rtischev during the signing of the Treaty of Turkmenchay in Iran in 1828

In the 19th century, Russian imperial expansion created new borders in the Caucasus and Central Asia5. The 1813 Treaty of Gulistan between the Russians and Iran’s Qajar dynasty gave the former a substantial amount of Iranian territory in the Caucasus, while the Treaty of Turkmenchay officially ended the last of the Russo-Persian wars6. According to Morrison, 1865 was the year that imperial Russia annexed Tashkent in Central Asia, and the years afterwards followed with the conquest of the Persian cities Samarkand and Bukhara7. Once these cultural centres had been absorbed, more territories within the region quickly fell8. Much later, after the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, the Russian language would become the lingua franca of the peoples of the Soviet Union9. In the 1920s, religion was banned, and indigenous and ‘religious’ scripts that had been used (e.g. Persian, Arabic, Hebrew, and various Turkic languages) were quickly replaced with Latin, and later, Cyrillic10.

By the 60s and 70s, Soviet filmmakers were producing high-quality, world-class pictures that also entered the mainstream. One of the most well-known Soviet easterns is Vladimir Motyl’s 1970 film, White Sun of the Desert. The film begins on the Central Asian shores of the Caspian Sea during the Russian Civil War that followed the 1917 Revolution, and follows Fyodor Sukhov, a soldier in the Red Army. Sukhov saves Said, who becomes his loyal Central Asian companion. Said represents a model Central Asian: civilised, loyal, and helpful to the Soviet cause. He is juxtaposed against Abdullah, a gangster whose nine fully-veiled wives he saves with Sukhov at the start of the film. Along their journey, Sukhov tries to convince the women to abandon polygamy and the veil. Believing they are his wives, they reveal their faces to him, embrace communism, and address him as ‘comrade’ Sukhov. ‘The Revolution has freed you’, he asserts. ‘You no longer have a master, so forget your cruel past. You will work for us freely.’ These women are mere props, naïve women who do not know any better and are seemingly okay with the supposed restrictions of their culture. No specific ethnic group or region is mentioned – only ‘Turkestan’, a Persian term denoting parts of eastern Central Asia; as such, many Central Asian peoples are painted with the same brush.

A still from White Sun of the Desert

Andrey Konchalovsky’s 1965 classic, The First Teacher, presents another example. The Kyrgyz Dyuyshen, a young komsomol in the Communist Party, claims he has come back from the army to teach the children of his village, and is met with laughter in response. Dyuyshen becomes angry with the villagers; ‘Who freed you?’ he asks. ‘Answer me: who freed you? The Soviet powers freed you, and they sent me here to teach.’ He convinces a few children to come under his wing, including Altynai, a teenage girl whose mother wants to marry her off. In the classroom, Dyuyshen lectures on Lenin and communism, claiming that capitalism, the wealthy, and mullahs are enemies, while only the proletariat are their friends. ‘I need to prepare you for the global revolution’, he says to the children, referencing the Soviet desire to spread communism far and wide.

Caucasians and Central Asians were never portrayed as complete people, but mere tools; the idea of Russian dominance, initially written about in pre-Soviet literature, had clearly found its way into film plots

It is because of the Russians that Dyuyshen is able to bring back his knowledge, experience, and hopes to better his society. He constantly praises Lenin and exclaims that his people have been saved by communism. Altynai suffers, and it isn’t until Dyuyshen returns that she can be ‘saved’ by his European ideas. This notion of using women to justify Russian imperialism can be seen in many such films, as well as in the book of the same name written by the Kyrgyz-Tatar author Chingiz Aitmatov. In many instances, writers and directors who sometimes encouraged these ideas were natives themselves who believed in European cultural superiority, or in communism as a unifying force between Russians and natives.

A still from The First Teacher

Stanislav Rostotskiy’s 1967 film, A Hero of Our Time: Bela, based on Lermontov’s eponymous novel, takes place in the northern Caucasus. Pechorin, a Russian soldier, had become entranced with Bela, the daughter of a Circassian Muslim tribal leader. She is shown performing a Circassian version of the lezginka dance and singing a Circassian song, both of which transfix Pechorin. He grows desperate when Bela doesn’t immediately return his love, and angrily retorts that other ‘wild Oriental women’ would have considered themselves lucky. ‘If Allah made me love you,’ he asks her, ‘wouldn’t he want you to love me back?’ The film often juxtaposes Russian and Circassian culture, cutting intermittently from the love story to the present, where a character named Maksim narrates. Throughout, the Caucasus is purposely used, as Pechorin needs exotic places to feel alive11. The region is therefore seen by him (who represents privilege and imperialism) as a means to satisfy the emptiness in his life12. Bela, too, is a conquest, an object to distract Pechorin from perpetual boredom. Eventually, despite her exotic essence, even she cannot make him happy13.

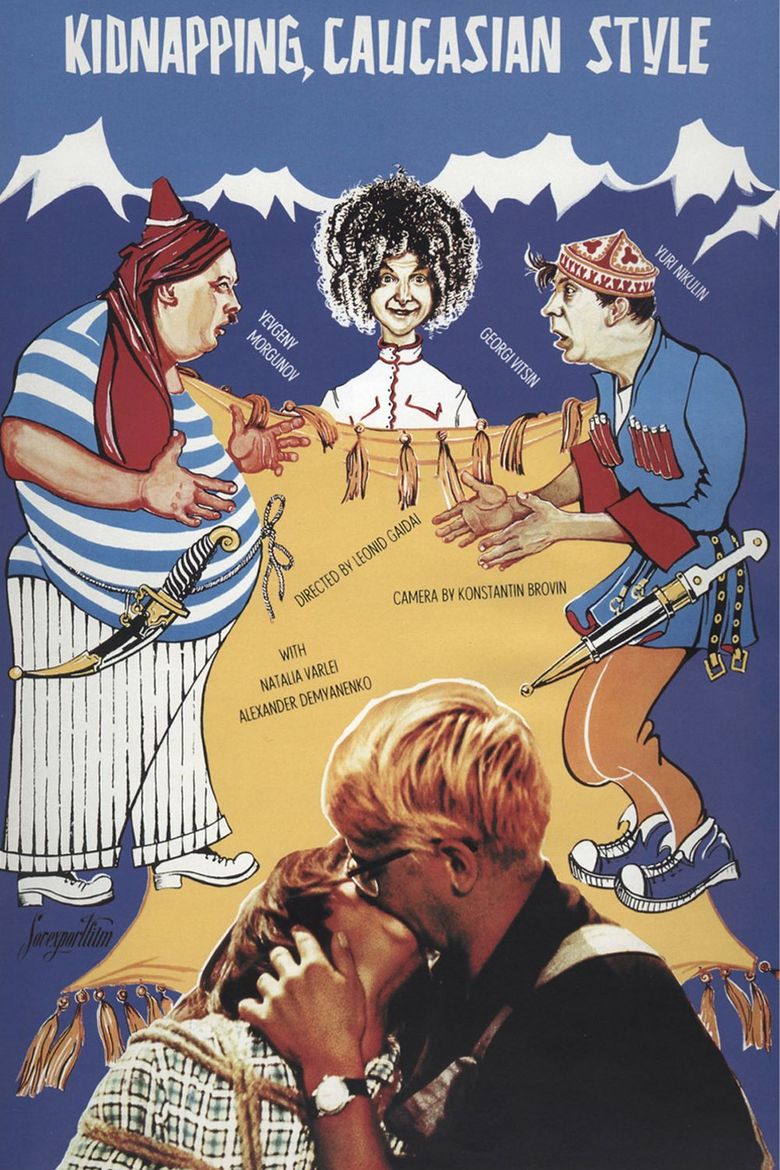

A promotional poster for Kidnapping, Caucasian Style

Leonid Gadai’s 1967 comedy, Kidnapping, Caucasian Style, is perhaps one of the most famous easterns with the Caucasus as a setting. Alluding to Pushkin’s Prisoner of the Caucasus poem and Tolstoy’s story of the same name, the film tells the story of Shurik, a Russian student who travels to the Caucasus to study indigenous rituals14. There, he meets Nina, who although is Caucasian, is also a modern Soviet. The Armenian actor Frunzik Mkrtchyan – the only actual Caucasian in the film – constantly brags that Nina is the ‘new example’ of the ‘ideal’ Soviet Caucasian woman. It is important to note that no specific ethnic groups are named; the characters are instead meant to be caricatures of the many peoples of the Caucasus, whether they be Armenian, Arani, Tat, Chechen, or otherwise.

In all of the mentioned films, Russian culture, if not explicitly shown, is at least implied to be the liberator of indigenous women, a force able to tame the animalistic, emotional, and passionate ‘Oriental’ nature of the people it is foisted on. While it is true that certain innovations were brought to Central Asia by the Russians, they were done so only after considerable damage had been done. Zamira Sydykova, a Kyrgyz writer, states that,

Local people … refused to fulfil Tsar Nicholas II’s decree of July 25, 1916 conscripting 400,000 men from the ages of 19 to 43 into support battalions in the Tsar’s army. This decree sparked a mass uprising across Central Asia that was put down by force and sent many Kyrgyz, Kazakhs, and Uzbeks fleeing to China to escape being killed at the hands of Russian soldiers.15

Russian soldiers on the Kazakh steppe in 1916

After the establishment of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), Russia yet again enforced ethnocentric ideals upon non-Russian subjects. In March 1919, Lenin established the korenizatsiya policy, (formed from the Russian words for ‘roots’ and ‘heritage’), in which ethnic groups were encouraged to speak in their languages, establish cultural centres, and set up government-funded theatres and newspapers dedicated to their cultures16. This was Lenin’s attempt at making peace amongst nations, and he believed that encouraging ethnic identity would make the Soviet Union’s minorities feel more comfortable. The policy, however, wasn’t spread across evenly, and the borders of the republics drawn by Lenin and Stalin didn’t always correspond to where certain ethnic groups felt at home.

When Stalin took control, he initiated the ‘Great Retreat’, a reversal of Lenin’s korenizatsiya. Lenin did not believe in Russian cultural domination, but Stalin – a Russified Georgian – reasoned that emphasis on cultural heritage would become a threat to the establishment. If people felt connected to their ethnic identities rather than their Soviet one, he argued, they might press to leave the Union17. Stalin’s purges began in 1933, when peoples such as Chechens, Circassians, and many others were relocated by force and subjected to genocide18. At the same time, Russians were sent to areas in which they were minorities in order to dilute indigenous populations, and the Russian language became mandatory for all19. However, because Stalin and Lenin’s approaches were so different, and policies were adapted as support was needed for the war effort during World War II, there was no consistency in the treatment of minorities20.

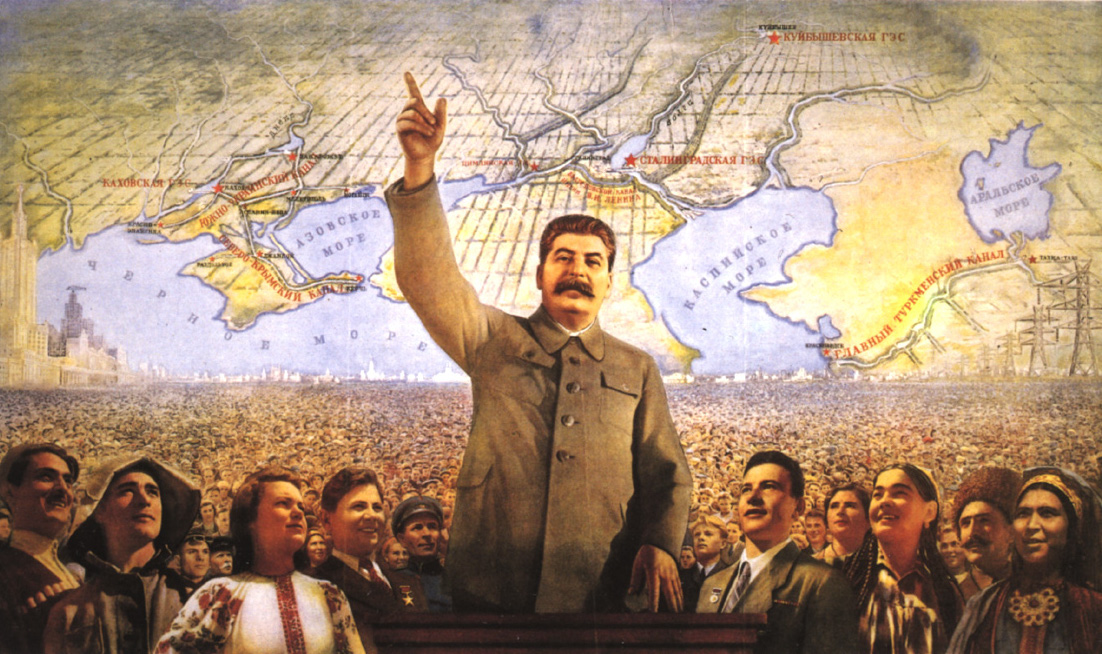

A detail of a Stalin-era Soviet propaganda poster depicting various peoples of the USSR united under communism

After Stalin’s death, Nikita Khurshchev ended Stalin’s ‘reign of terror’ and began the ‘moulding of all nationalities into a ‘Soviet Person’, where ‘the concept of being “international” was pushed’21. There was also the previously mentioned notion of Russians being ‘big brothers’ to all other Soviets, and this further stoked tensions between Russians and non-Russians22. This strife, with roots in the inconsistent nuances of Soviet policies, would later be replicated on screen.

In the above-mentioned Soviet easterns, as well as many other films produced in the same vein, Caucasians and Central Asians were never portrayed as complete people, but mere tools; the idea of Russian dominance, initially written about in pre-Soviet literature, had clearly found its way into film plots. The historical conquests of the Caucasus and Central Asia, Saidian-Orientalist writings, and Soviet policies regarding ethnicity and nationality (e.g. ethnic cleansing, relocation, and korenizatsiya) all shaped the ways in which the people of the two regions were portrayed in film. This not only justified the colonisation of the Caucasus and Central Asia, but also the spreading of the ideals of communism and secularism – two major pillars of Soviet ideology – in order to serve the state.

Mikhail Galustyan as Jorik Vartanov on Nasha Russia

Today, many Caucasians and Central Asians tend to overlook history, laughing along with the jokes in Kidnapping, Caucasian Style, and watching contemporary Russian variety shows such as KVN, Nasha Russia (Our Russia), and Comedy Club, the latter of which is hosted (and partially produced by) Armenian comedian Garik Martirosyan. While humorous, these programmes portray many of the aforementioned stereotypes, depicting Caucasian men as hyper-masculine, hairy, and in constant need of dancing. In the sitcom Druzhba Narodov (Friendship of Nations), for example, the main character, an ethnic Lezgin, constantly tries to explain to his Russian wife why his relatives are so uncivilised.

I often sit on my parents’ couch, noticing their laughter as the television blares loud and sometimes degrading jokes about the place I still regard as home. I question them, knowing the brutal and tragic history behind the humour, knowing that we’re watching television in the Russian language at the expense of communicating in our own native one. What’s lost is lost, but watching Makhachkalinskiye Brodagi (Vagabonds from Makhachkala), a mutli-ethnic comedy group from Dagestan, gives me a sense of pride. On another show, the Armenian comedian Mikhail Galustyan, with eyebrows exaggerated by makeup and a thick accent jokingly claims that no other cuisine beats that of the Caucasus. I think about my father’s kebabs, my mother’s dried fruit plov, and my grandmother’s kurze, and laugh, too.

Click here to download this article’s bibliography.

Cover image: a still from White Sun of the Desert.