Getting messy with Morocco’s Soukaina Joual, in the flesh

Soukaina Joual is not afraid of blood, and doesn’t understand why anyone else would be, either. I know this because I spent a weekend with her in Fes in Morocco for an arts conference, during which we joined an organised group tour at a local horse clinic. Joual is from Fes, where horses and mules play an essential role in the economic circuit of the city’s old Medina, one of the largest pedestrian-only areas in the world. Halfway through the clinic tour, I wandered into a stable to find the guide explaining an ongoing procedure in which veterinarians were amputating a horse’s tongue. Crouching in front of the horse, staring into the silver sea urchin of needles and instruments clustered in its mouth, was Joual.

Flesh and blood lend much inspiration to Joual, a 26 year-old artist whose first step in 2017 will be a residency at Rabat’s historic l’Appartement 22, which has seen the likes of Mona Hatoum and Adel Abdessemed cross its threshold. Her art spans multiple mediums and often invokes the raw, the red, and the repulsive. Because of its vivid imagery, it sometimes darts into the territory of gore; but what makes Joual’s pieces so provocative in particular is the playfulness involved. There is an underlying gesture in her oeuvre that swivels like a weathervane between the fake and the real. A piece like Saucisse may have all the similarities and texture of a sausage, but it is deceptive, a bloody ruse crafted from acrylic and clay. ‘It’s interesting – when people see meat, they have such a strong reaction’, Joual tells me. ‘It’s just something that exists beneath your own skin. I don’t think I’m using meat or this image of meat to shock; it’s a way of expression.’

A still from Aggression of the Simulacrum

This is the hitch in Joual’s work; meat is ubiquitous. As scholar Nick Fiddes once said, it seems like ‘anything but a symbol – it is substantial: literally, in the flesh’. And yet, to peel back and expose meat reveals many of the meanings, orthodoxies, and subterraneous fears that people have layered onto its material existence.

Joual, who listens to my stories of high-school biology dissections with interest and a little envy, saw her childhood revolve around meat as an everyday commonality – and commodity – while growing up in Fes. She has memories of watching the Eid al-Adha sacrifices and getting lost in the streets of the Medina, where butcher shops show a customer the chicken alive, before they buy it dead. After a stint up north at l’Institut National des Beaux-Arts in Tétouan, she began channeling the subject of meat and its imagery into her work, and today still finds herself surprised by people’s reactions. ‘What I found funny is that even people here who are used to seeing meat … pull back. They say, “Oh, that’s too much”’, remarks Joual. ‘I’m especially surprised by the women. How can you be disgusted by blood? You’re bleeding every month!’

The Arab World (detail)

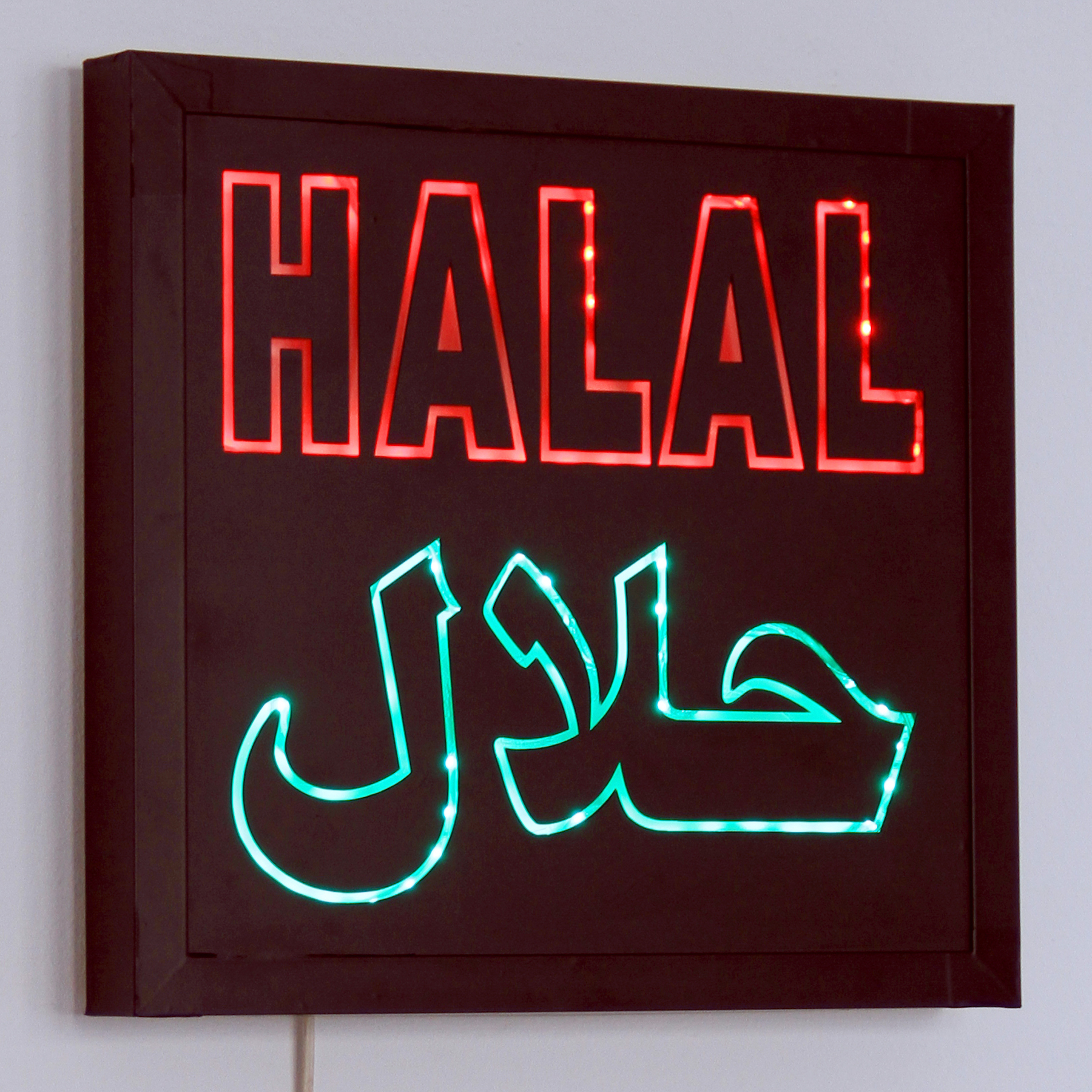

Much of Joual’s work explores meat’s presence in Morocco and the surrounding region. The Arab World, which she presented in 2014, is a map of the Middle East and North Africa reconfigured as a wall of packaged raw beef. Meat’s link to violence is an easily made one, and it only takes the viewer another thoughtless step forward to affix the MENA region onto that relationship; but Joual avoids the obvious constellation of meat-violence-Arab world, instead tinkering with a type of humour that seems almost prankish in how it addresses viewers. For example, an LED sign with the word ‘halal’ blazed into its surface may seem to signal vaguely towards meat’s position in a religious value system; yet, a second look discloses the mutually informative relation between language and sense of place that undergirds much of Joual’s work. ‘When I commissioned a man to make the panel for me, he asked me, “Why do you need the halal panel? Everyone knows meat here is halal”’, Joual recounts. ‘I said, “No it’s not for the Moroccans – it’s for the foreigners”, and he said, “Ah yes, you’re right”’. At this, Joual laughs: ‘[It] doesn’t make sense, but he totally followed the logic’.

There is an underlying gesture in Joual’s oeuvre that swivels like a weathervane between the fake and the real

The joke of the piece is perhaps its own redundancy. The sign’s neon glints slyly off people’s own assumptions, showing how attitudes towards meat are so unthinkingly rooted in personal context; Halal panels can be seen as a necessity, a logical fixture in the urban landscapes and immigrant neighbourhoods of Europe and America. For many, the sign is commercial and utilitarian. For the panel-maker, a halal sign in Morocco can only make sense if it serves the [mostly non-Muslim] European tourists who frequent the Medina. All have been fooled, maybe. What is the sign’s real audience? Joual shrugs, and then says, ‘The foreigners’.

Halal Stamp

In The Art of Cruelty, Maggie Nelson writes that the ‘The spectre of our eventual “becoming object” – of our (live) flesh one day turning into (dead) meat – is a shadow that accompanies us throughout our lives’. Joual’s work leans into this shadow, facing its terror head-on, while still blurring the line between dead and alive. In I’m Not So Innocent Anymore, her first performance piece, the artist takes two kilos of meat, slices them, and then manually grinds them for a mind-numbing and repetitive 45 minutes. ‘Flesh: I don’t know if I can call it alive or dead’, she tells me. ‘At one point it will rot, it will change. In a way, it’s still alive.’ The performance is about killing, of course, but also transformation and – another dry quip – the boredom that can be found in both processes.

Though meat is a thematic strain in her work, Joual’s art perhaps finds its existential base in Morocco. Throughout a nascent career that has taken her around the country and as far as South Korea for a residency at the Seoul Art Space Geumcheon, Joual is always returning home. Her second performance piece, in which she attends a mass protest in Seoul while wearing a mirrored cube on her head, evokes a Daft Punk-esque techno-future of dissent, wherein the watched and the watcher become endlessly confused. Whether it is Joual’s own observance of the protest, or the bystanders taking photos of her (and in turn, themselves reflected in her mirrors), the beam of surveillance bounces back and forth endlessly. The performance contains an associative relationship with Morocco, where surveillance has a different, more intimate nature. ‘In Seoul, you don’t have to worry about your purse on the subway because of all the security cameras’, Joual says. ‘Here in Morocco, the surveillance often comes from the people around you. It’s very different when it’s a pair of someone’s eyes watching you.’

Holy Knives

In 2016, Joual took a look at dissent in Morocco with Holy Knives, a set of stainless steel knives engraved with variations of the Arabic word madhbuh. The literal translation is ‘slaughtered’, but in Darija, the colloquial dialect spoken in the country, the word has another sense that comes closer to ‘screwed’ or ‘damned’. According to Joual, it can be used in rock-bottom situations that offer no exit: ‘Like saying, “Yes, everyone’s slaughtered, we’re fed up, the situation is awful”’. At a time when the international art world often turns to Arab artists for social commentary, sometimes prioritising their political existence over their aesthetic inclinations, Joual has kept the circle small, giving audiences a piece that reads like an inside joke for an entire country.

Over a plate of cold, salty fries at a café in one of Fes’ busy roundabouts, Joual summarises for me the gist of her work: ‘I am from Morocco. I was born and raised here. And I get inspired from this place.’ Pointing to the café’s refrigerated display, in which sausage links and kebabs have been laid out like pieces of jewellery, she adds, ‘I see this image, and I want to take that whole thing and put it in a gallery. I want to say, “This is art.”’