Arrr! Introducing the badass sounds of Pashto pop from Afghanistan to new audiences

Imagine taking a tour of a university in Peshawar and having staff and guards abruptly begin to rush you into a car driving hurriedly out of the compound, as militants head to attack the university. It is under such chaotic circumstances that Pakistani native Abeera Arif Bashir and Timothy P.A. Cooper of Pirate Modernity first discovered Pashto pop music in 2013. Their experiences mirrored, albeit coincidentally, the very same conditions under which such music is made.

Having lived in Pakistan for the better half of a year, the two were working on developing partnerships between universities based both in Pakistan and the United Kingdom. The threatening militants were coming after having been made aware of the presence of Westerners, the presence of Western garments and a woman without a headscarf at the said university in particular. It was not until on the way back from their hasty escape, after the militants had indeed attacked the university, that the car happened to stop at a service station where Arif Bashir snuck a glimpse at some Afghan pop cassettes behind religious ones.

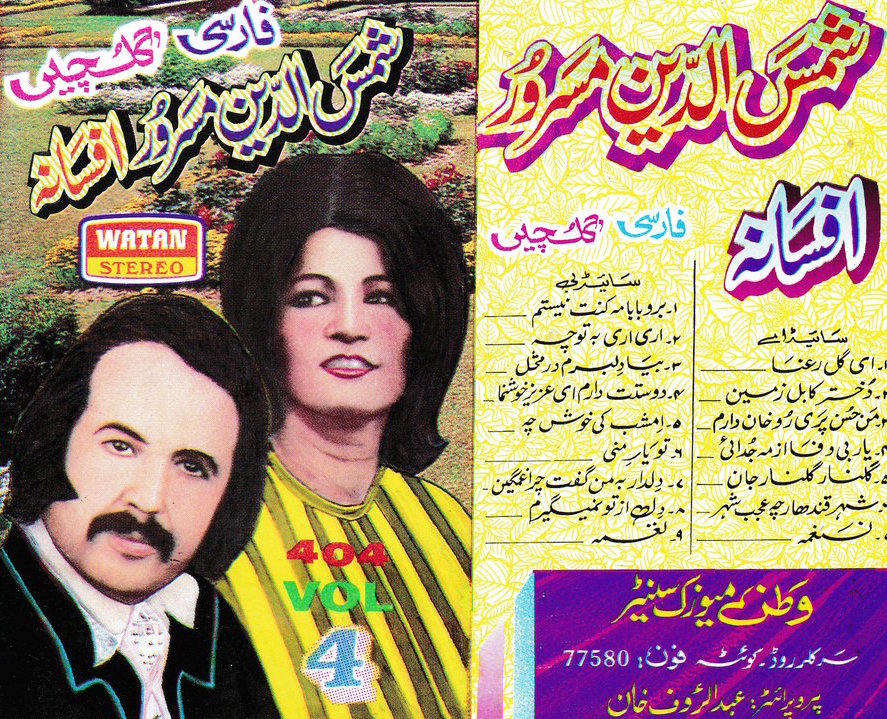

Shamseddin Masroor and Afsaneh

Soon after, entranced by the sublime high-octane tunes, the two began to collect tapes in media markets around the area with the intent of playing and sharing them. With Pakistan as the host to the greatest number of registered Afghan refugees – approximately 1.5 million, 85% of them being ethnic Pashtuns – it makes it clearer why Arif Bashir and Cooper collect many of their cassettes from not only Kabul, the epicenter and capital of Afghanistan, but Peshawar (a city in northwest Pakistan close to the border) as well, . Upon their return to London, the two scoured grocery stores headed by Afghans of the diaspora in London.

‘[We] asked them things like, “Do you have cassettes like a library, and do you still have them?” And they were like, “Yeah why?” “We’d like to buy them.”’ Cooper continued excitedly to state the shop owner’s confusion as to why the couple had wanted tapes instead of CDs, as cassette tape culture has rapidly declined within the past decade. Aside from the historical value of such tapes, Cooper also attributed sonic superiority to their preference of cassette tapes and the inner ‘technological purist’ in him.

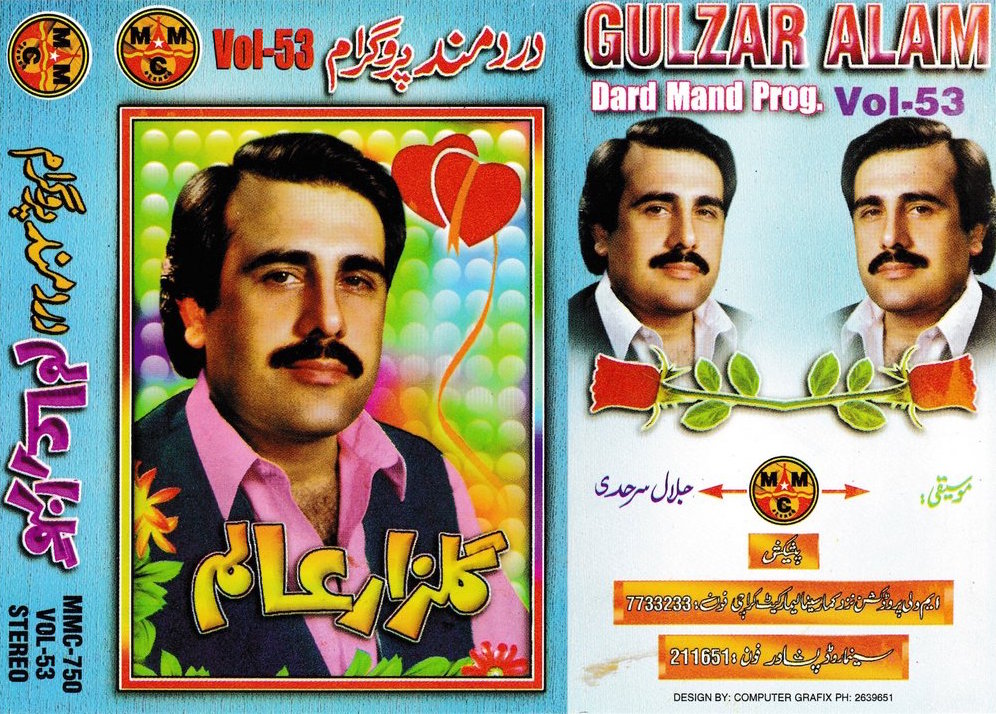

Gulzar Alam

After amassing a large archive of Pashto pop music from the late 90s to the early 2000s, the two were discovered whilst DJ-ing by the acclaimed online radio station NTS, well known amongst the alternative music scene, and were asked to play a monthly show this past April. Thus began Pirate Modernity and the duo’s attempt to revive and introduce Pashto pop to a larger, diverse community. A favourite of underground music platforms and frequently featured as curating choice mixes, Pirate Modernity often play shows at SOAS at the University of London, as well as underground and experimental music venues in the city such as Rye Wax and Café Oto.

Psychedelic backgrounds with rainbow-gradient typeface, bulging hearts, single roses, and water ripples promise trance-like music and hint at what is to come

Known as having the world’s largest protracted refugee situation and making up the second-largest refugee group in the world (according to the UN), Afghanistan and its people are hardly what one typically associates with astounding pop music. However, it weighs true, as Arif Bashir and Cooper claim, with Pashto pop’s notorious impassioned improvised drumming and heavy use of Autotune.

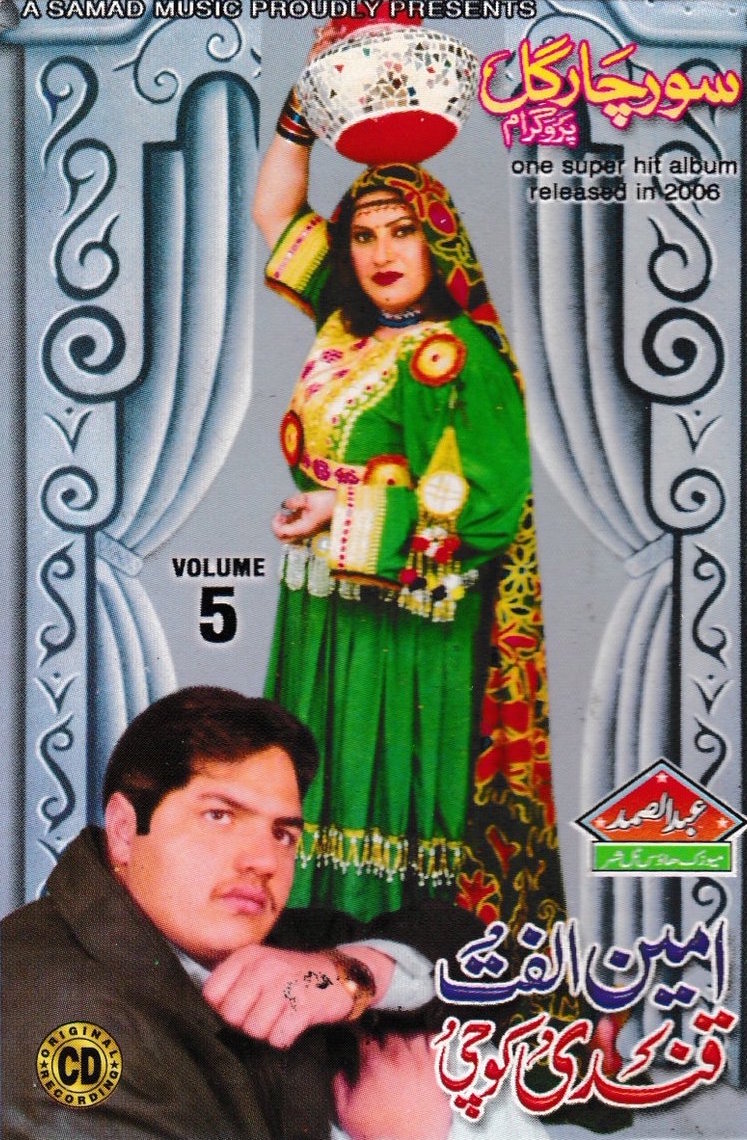

Amin Olfat and Ghandi Kuchi

The graphics and visual culture of Pashto pop cassettes are arguably just as compelling as the tonality and orchestration of the music. Similar to the generous appliance of Autotune, images are highly photoshopped and exorbitantly saturated with Pashtun musicians depicted as heartthrob heroes, often with clasped hands and dreamy looks. There is a ferocious liveliness in the candy-coloured cassette covers that demands attention and challenges regimentally imposed austerity and restrictions. Psychedelic backgrounds with rainbow-gradient typeface, bulging hearts, single roses, and water ripples promise trance-like music and hint at what is to come. Interestingly enough, the cassette tapes themselves are not subject to such creative freedom and come in their standard shapes and colours. The covers boast the artistic handiwork of the graphic design studios by proudly labelling their contact information, rather than recording studios, indicating the increasingly problematic grey areas in Pashto pop recording and distribution.

Attesting to the genre’s literary merit of its poetic couplets, Pirate Modernity also seeks to reverse pop’s notoriety amongst the Afghan community as ‘low-brow’, as many prefer more classical and sophisticated Afghan music. ‘A lot of successful musicians whose craft intertwines with the art of poetry look down on pop music because it’s considered to be wedding music; it’s considered to be cheap, [and for] people of lower moral standing’, said Cooper.

Poetry, however, is an integral component to Pashto pop music. Many Pashto pop songs feature ghazals, which are couplets with specific and intricate rhyme schemes. These are interwoven with a highly energetic and fiercely rapid instrumental session in the songs in order to create melodic canonisations of Pashto pop. Such use of ghazals is similar to that in oral traditions of Afghan culture, such as the poetry sung by Pashtun village women and made famous by Professor Sayd Bahodine Majrouh in his book Songs of Love and War: Afghan Women’s Poetry. One can compare these lyrics of unrequited love and pain to Pashtun pop star Naghma’s lyrics, Alama nor me de khwago khwago zra mor shawe / Pa tarkho sanga sok maregi mala chal razi, which roughly translates to, ‘My heart is too full of this “sweet sweet” in this world / But how can one be full by eating bitterness? I don’t know this trick’. In her ode to her beloved, Naghma suggests this paradox of bitterness juxtaposed with love and synonymises it with insatiability.

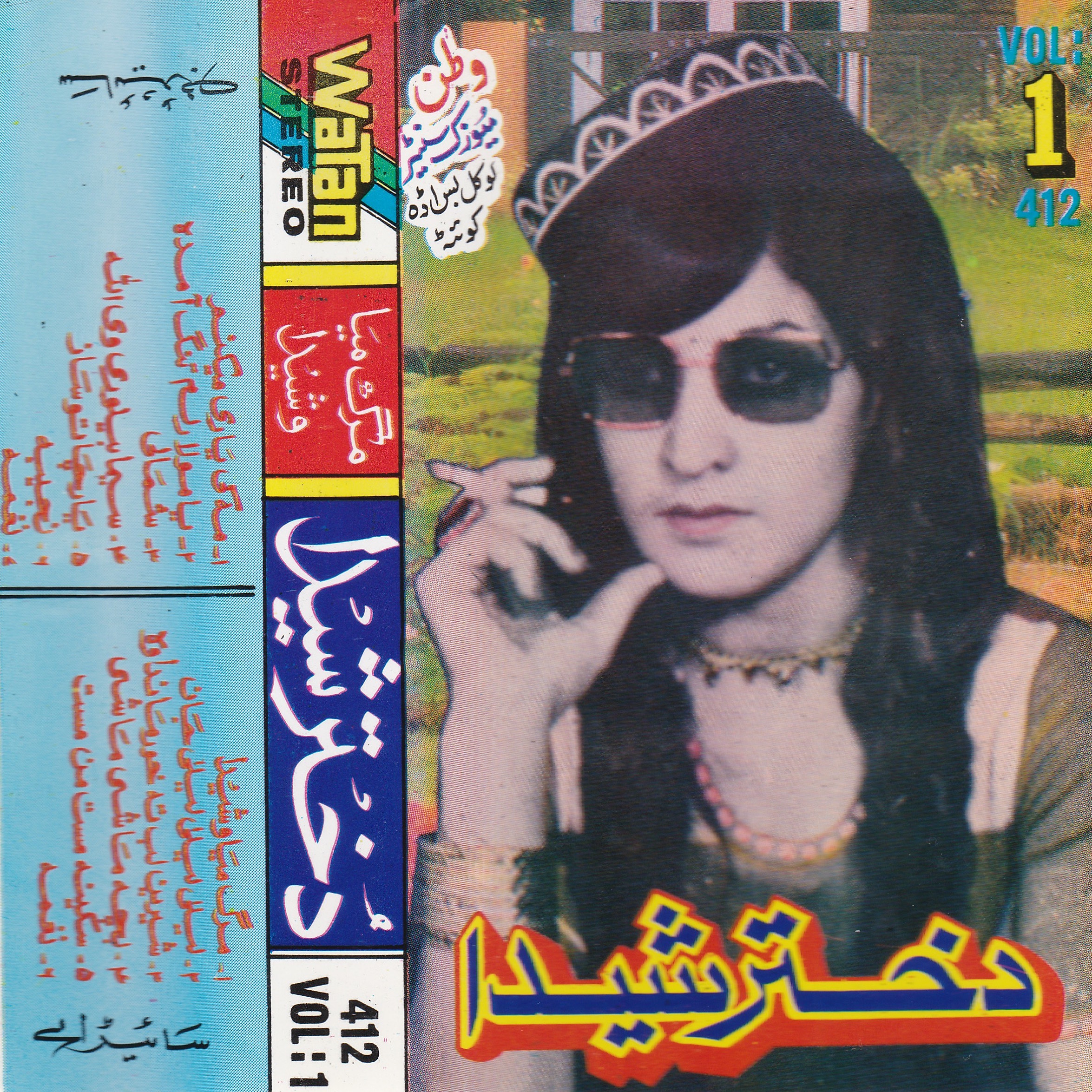

Nazia Iqbal

Cooper and Arif Bashir also asserted that Pashto pop has archival signification not only where Afghan culture and poetry are concerned, but history as well. ‘There’s a bottomless pit of interesting stuff no one has done anything with, [and an] amount of things that can come from it’, said Cooper. ‘There’s the analysis of the weaponisation of languages in the songs near the 2000s with the onset of the American invasion and subsequent drone strikes where you get this kind of language coming in the songs, like [the lyrics], “Your eyes hit my heart like a drone strike”’.

Following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 and the rise of the Islamist Muttahida Majlis–e–Amal (MMA) in Pakistan, music such as Pashto pop, common to both countries, was targeted. ‘They banned music, they banned cinemas, they banned every sort of entertainment’, said Arif Bashir when referring to Pakistan. This context, however, gives more value to Pashto pop and more of a reason for Pirate Modernity to spread exposure, as Cooper argued. ‘The Taliban in Afghanistan didn’t ban] music – they banned musical instruments. It’s important to remember that the Taliban had their own musical aesthetic; they just banned the instrumentation, which led to mass riots against people who were selling cassettes.’ Some statistics also came to Cooper as he remembered the era. ‘Every cassette seller was targeted and attacked; and musicians were targeted, and musicians were attacked, and musicians were killed … In this period I think about 18 – 20 musicians were killed for a period of about four to five years.’ Cooper continued to describe the main force compelling him and Arif Bashir as Pirate Modernity. ‘I can’t imagine anywhere on earth at that time where it was more dangerous to make music’, he said. ‘[These cassettes] are not only incredibly accomplished and astonishingly pieces of music, but also driven by people in difficult situations making them.’

Noor-Mohammad Kavazi

Today, Pashto pop is in fact thriving within both Afghanistan and Pakistan, as well as in the Afghan diaspora. However, with cassette tape culture on the brink of extinction, and today’s Pashto pop being heavily influenced by Bollywood and Western music, there is less emphasis on Afghan instruments such as the robab and dohol. One can still find Pashto pop with folk instrumentation at weddings and gatherings, though, as they are highly popular for traditional Afghan dances like the attan. Pirate Modernity’s archive and shows of Pashto pop, particularly in the form of cassette tapes, is important not only for showcasing Afghan culture, but also keeping alive significant aspects of Pashto pop that many have died or fled their homeland for. Thanks to the likes of Cooper and Arif Bashir, one need not own a Walkman or wait for an invitation to an Afghan celebration to listen to some of the finest Pashto pop.