Bringing together past and current generations of Iranian artists through works on paper

A small section in the middle of the lower ground floor of the British Museum has a beautiful red carpet laid out, and surrounding walls adorned with a selection of recent acquisitions of works on paper by Iranian artists from both inside and outside Iran. The works – collages, drawings, artist books, and photographs – fill three glass cases standing on both sides of the carpet. Of the two walls devoted to the exhibition, the entirety of one has been given over to a series of collages by the late modernist Bahman Mohassess. A notable work entitled Pour Munch is a nod to Edvard Munch’s 1944 The Scream, in which a grotesque, animal-like figure mimics the Norwegian original. Similar misshapen figures are present in the other works by Mohassess, complete with twisted and warped visages. His figures can be described as bestial, as they certainly do not appear human. A shark, for example, serves as an allusion to the late Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, who served as Iran’s president between 1989 and 1997 (and who was often likened to the sea creature – kuseh in Persian). To the right-hand side of Mohassess’ collages is the artist’s own portrait, taken by Ahmad Aali, often referred to as the father of fine art photography in Iran. The black-and-white image shows Mohassess seated in front of one of his mythical artworks, facing away from the camera. He looks pensive, and seems far more serious than the artworks the photograph has been placed beside.

Bahman Mohassess - Kuseh

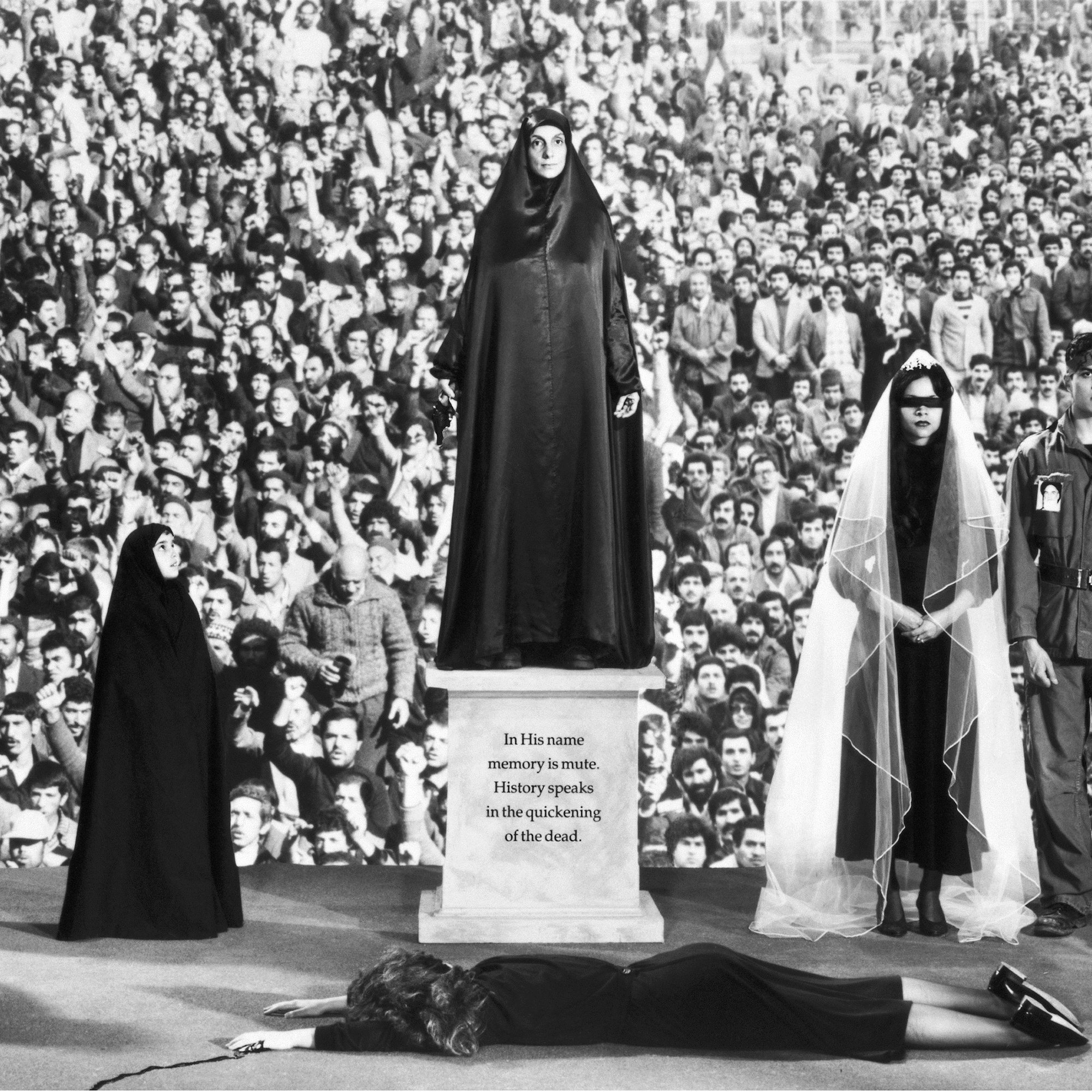

Directly opposite Aali’s image is a composite photograph that has been put together by Mitra Tabrizian. Surveillance depicts three different time zones in one image moving from left to right in a non-chronological order. Firstly, she shows the 1953 coup d’état, then the Iran-Iraq War of the 80s, and lastly, the Iranian Revolution. Women are at the forefront of Tabrizian’s image; they take centre stage in front of a crowd that looks to be full of men. At the end of this particular wall hang two more images focusing on women by New York-based artist Nahid Haghighat, who reveals a woman removing her headscarf in Escape, a 1975 aquatint. Nestled in-between Tabrizian and Haghighat’s work – dark, monochromatic images – lie a series of red and green digital prints by Parastou Forouhar. While Forouhar’s work is more colourful, the sentiment it conveys it less so. In the accompanying wall text is a quote by the artist from 2002, which reads:

All surfaces are covered with vibrations of patterns. They represent the harmony of the world … But this untouchable harmony can only be appreciated from a distance, as it conceals a great potential for brutality.

Mitra Tabrizian - Surveillance

While these words were quoted six years before Red is My Name, Green is My Name was made in 2008, they perhaps couldn’t describe the work on show at the Museum more perfectly. At first glance, Forouhar’s work could be seen as containing beautiful fabric patterns, covered in geometric shapes. However, on closer inspection, the viewer is faced with contorted figures who have become devoid of identity as a result of their faces and eyes having been covered with their hands or black bandaged strips.

Iranian Voices provides a unique and novel look at how generations of Iranian artists, past and present, have been utilising a simple, yet powerful medium to tell their stories

The subject matter is somewhat lighter in the two vertical glass cabinets at either end of the exhibition space. In a move away from politics, a number of pieces heavily influenced by the Shahnameh (Book of Kings) of Ferdowsi are on display. The works of Ali Akbar Sadeghi, Mohsen Ahmadvand, and Shahpour Pouyan have revived the Shahnameh for 21st century audiences. Sadeghi has done this in the form of animation, ‘modernising’ Ferdowsi’s epic through movement, while still keeping his characters clothed in traditional dress. Ahmadvand, however, has given the hero Rostam a millennial-style makeover, showing him wearing a t-shirt and jeans beneath the helmet he made of the skull of the White Div (devil) of Mazandaran. Ahmadvand’s trendy Rostam has been placed against a blank background, as though truly having walked out of antiquity into the present. Pouyan, however, goes a step further than Ahmadvand by eradicating Rostam completely, as he’s done with figures in a series of modified Persian miniatures by the likes of Kamaleddin Behzad and others. Displayed beside a 16th century miniature depicting the famous scene of Rostam slaying the White Div, Pouyan’s After Rostam Slaying the White Div shows a near-identical image in which a blank space replaces Rostam. By doing this, Pouyan creates a cavity forcing the viewer to look at the surrounding imagery and away from the narrative.

A still from Ali Akbar Sadeghi’s Boasting

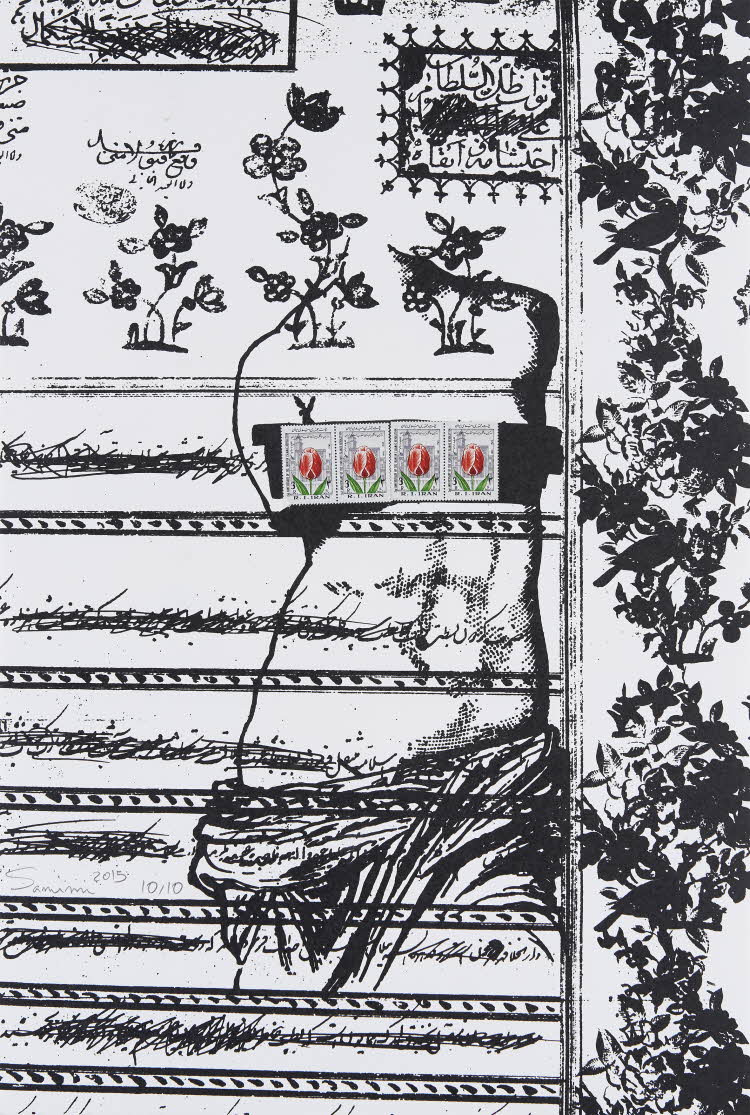

At the other end of the gallery, opposite the Shahnameh-inspired pieces, is a case filled with collaborative works by artist couple Tarlan Rafiee and Yashar Samimi Mofakham in the form of silkscreen prints with heavy, black calligraphic outlines. The images reference classical works of Western art such as the Venus de Milo. Mofakham’s figure, however, has been beheaded, while her breasts have been censored and covered by Iranian stamps celebrating the anniversary of the Iranian Revolution. Rafiee’s works, while visually in the same vein as Mofakham’s, are a little less politically charged in their colourful depictions of pop icons such as Googoosh, which have been made to reinforce the notion that Iran is about more than just the politics reported on in the West.

The case resting on top of the red carpet plays host to a series of works displayed flat. Amongst these are portraits by Afsoon, whose subjects have come from old family photographs. The sentimental collages look like linocut prints with their heavy use of black and the odd pop of red and blue accessories. The artist has said that the images were created to stretch her heart, in reference to the Persian expression ‘My heart has shrunk for it’/Delam barayash tang shodeh ast. Afsoon’s figures have been cut off below the shoulders, and likewise, bodiless portraits have been made by Shideh Tami. Tami’s handmade artist book displays two heads side by side, both depicted against golden backgrounds with the artist’s poetry written around them. These verses discuss light and darkness, the left-hand image being composed of a black calligraphic outline and the opposing right-hand figure being completely white.

Yashar Samimi Mofakham - Thirty Years

Beside all the work on paper, sculptures by master artist Parviz Tanavoli have also been included in the exhibition. These are shown in the form of a small bronze medal depicting a hand holding a bird, as well as one of his famous Heech (‘nothingness’ in Persian) sculptures. Beside the medal is an illustration made by the artist, inspired by a page of a book (Ghazvini’s The Wonders of Creation and the Oddities of Existence) Tanavoli had found in a flea market. The inclusion of the sculptural work has perhaps been included to remind audiences that drawings, while often overlooked, frequently serve as the beginnings of subsequent pieces. With Tanavoli being one of the most important contemporary Iranian artists around, the addition of his pieces is even more noteworthy.

Iranian Voices, while small, covers many subjects, styles, and disciplines. The two commonalities of the artists’ Iranian ethnicity and their having made works on paper has allowed for diversity to come together in the centre of the British Museum’s Addis Gallery to form an intriguing and memorable display. With works on paper usually receiving less attention than their canvas and photographic counterparts, Iranian Voices provides a unique and novel look at how generations of Iranian artists, past and present, have been utilising a simple, yet powerful medium to tell their stories.

‘Iranian Voices’ runs through April 2, 2017 at the British Museum.

Cover image: Bahman Jalali - Image of Imagination.