Disco-taxis and pretty girls: in search of the world’s oldest windmills in Iran

The sun burned hot on the roof of the car as we drove on the desert road near the frontier town of Taybad. In an effort to drown out the roaring and rattling of the engine, our driver cranked up the radio, making the forty-year-old Paykan bounce up and down on the beats of the Persian pop tunes he liked. I was in the back, squeezed between two old Afghan gentlemen dressed in blue robes and turbans on one side, and a rolled up carpet on the other. My friend, sitting in the front, looked over his shoulder and grinned as the dusty mountains of Khorasan towered above us. We were in Iran, the land of the Lion and Sun, and were looking for the oldest windmills in the world.

Although windmills are perhaps what the Dutch are best known for, our national claim to windmill fame is dubious at best. The Belgians, for instance, currently have more windmills in their country than we do, and the first windmill in the ‘Low Countries’ was actually built in France, just over the border near Dunkirk, in 1198 A.D.1 A similar issue actually surrounds our other most famous symbol, the tulip (from the Persian dolband, meaning ‘turban’), which was first brought westwards from the Ottoman court of Suleiman I by a Flemish botanist – but that’s a different story.

The author overlooking the plains of Persepolis (courtesy the author)

The historical origins of the windmill are shrouded in mystery. Water-powered mills were certainly built by Hellenistic engineers in ancient Greece2, but the ‘invention’ of the windmill – that is, the notion to use wind to power a machine – didn’t happen until several centuries later3. A common anecdote regarding the first windmill has been told by several early post-Islamic Arab historians, and revolves around a certain mid-seventh century Persian: Pirouz Nahavandi. While the story has been told differently by various sources, it roughly goes as follows: the Sassanian soldier Pirouz is captured and enslaved at the court of second Caliph of Islam, Umar, in Medina. There, he boasts about his capabilities as a carpenter. His skills as a carpenter are so extraordinary, he says, that he can build a machine powered by the wind. After hearing of this bragging, Umar challenges him to build the machine, to which Pirouz replies, ‘I will build a windmill that the whole world will talk about’4. Unfortunately, before he got around to building his windmill, Pirouz killed Umar with three (or six) stabs of his dagger; as such, to this day, Pirouz has been remembered more as the murderer of the Caliph than the first windmill builder. His supposed tomb near the province of Kerman in Iran is still a popular place of pilgrimage for nationalist Iranians and windmill enthusiasts alike.

Have Paykan, will travel (courtesy the author)

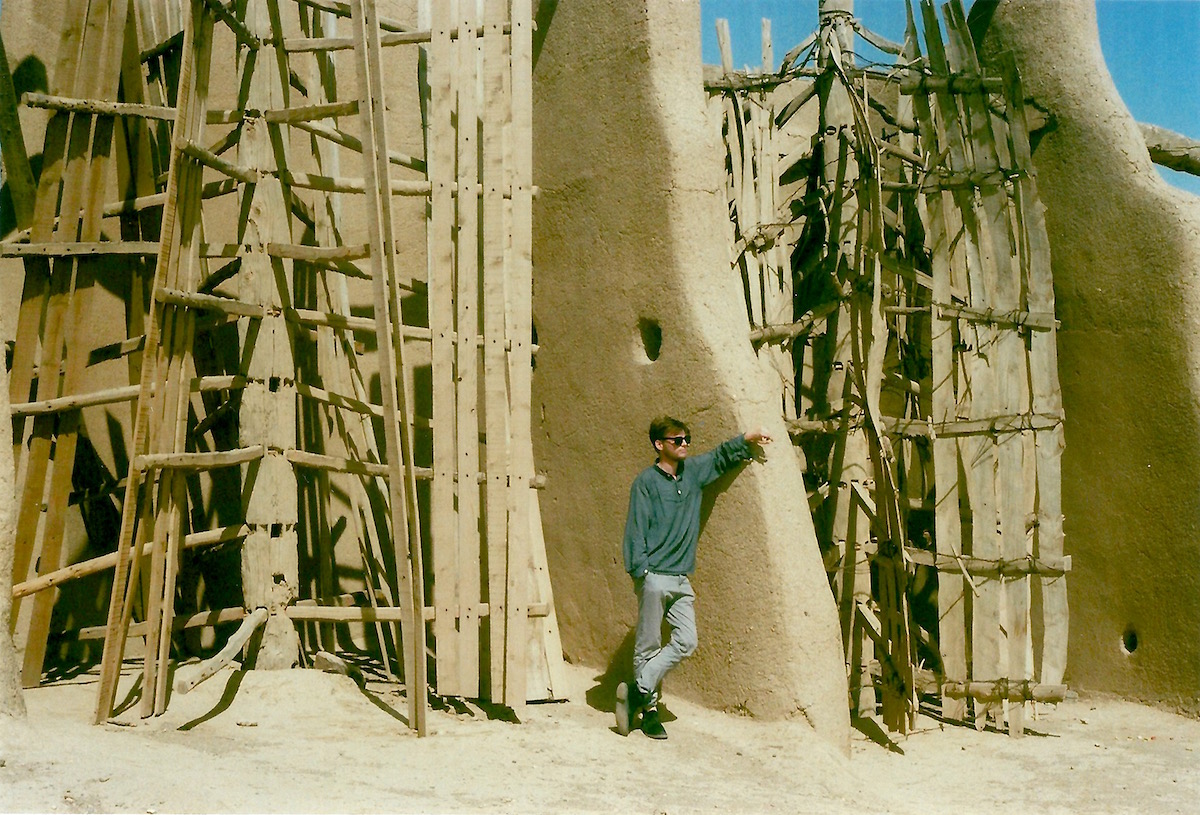

Some time later, in 947 A.D., the Arab historian Mas‘udi wrote: ‘[Sistan] is a land of wind and sand. There, the wind drives the millstones and draws water from wells for irrigation. There is in the world – and God alone knows it – no place where more frequent use is made of the wind’5. Unknowingly, Mas’udi made the first written reference to a windmill. He referred to the windmills that were probably common at the time in the eastern part of the Iranian plateau, in the present border area between Iran and Afghanistan. Every summer, a northerly wind sweeps across Sistan and southern Khorasan. Known as the bad-e sad-o-bist ruz – the ‘wind of 120 days’ – it stirs up sandstorms and causes a general nuisance; but in the past, it powered hundreds of windmills. The first drawing of Sistani windmills can be found in the Cosmography of the geographer al-Dimashqi, written around 1300 A.D6. Unlike their European counterparts, these Persian mills turn in the horizontal plane (think of a revolving door). By building a mud-brick windmill on top of a hill, the 120-day wind can blow through the structure, making the six (or more) sails revolve. The millstones are situated in a room underneath the sails.

Windmill chic (in Nashtifan, Khorasan province; courtesy the author)

Almost thirteen centuries after Pirouz told the court of Umar about his windmill-building capabilities, our luggage rolled off the baggage belt in Tehran, under the watchful eye of a gigantic portrait of Ayatollah Khomeini, woven in a carpet. I had persuaded one of my friends to be my traveling companion (who doesn’t want to go look for windmills in a hot desert?). After the photo of the grinning farangi on my visa had been carefully studied by the heavily moustachioed customs officer, he said, ‘Khosh amadid. Welcome to Iran’, and we set off.

In my mind, I saw the dancing Sufis, still dancing about the fire, the spirit of Sheikh Ahmad-e Jami, embodied in the pistachio tree, watching over them and the windmills

In Europe, very little is known about the Persian origins of the windmill. Only one study has been carried out on the modern whereabouts of these mills, based on a trip made by the British windmill historian Michael Harverson in the 1970s. Armed with his book Persian Windmills and a Persian phrasebook, we headed east for Khorasan. When I say that little is known in Europe about the Persian origins of the windmill, this is as much the case in modern Iran. As a foreigner on the street, many people come up to you to have a chat: ‘Where are you from? What are you doing here?’ Do you like it?’ The answer, ‘Hollandi hastam, and we’re looking for Iranian windmills’ caused lots of confusion, and my miming of a windmill resulted in several of our new friends thinking I ran a business in ceiling fans. Luckily, one of these new friends, Davoud, whom we met in Mashhad, did not think I was absolutely bonkers when I waved my arms around pretending to be a windmill. ‘Asiyab-badi’, he said nonchalantly, as if he were Pirouz Nahavandi himself, while blowing out some smoke of the lime-scented ghalyan we had gathered around. ‘My family is from southern Khorasan, and I can take you to the windmills’, he said.

Living the chai life (courtesy the author)

First, though, we had to go and meet his cousin. ‘She runs a café in the city and can teach you how to properly swear in Persian’, he told us; and before we knew it, we were crammed into a taxi with some more cousins of Davoud who had appeared out of nowhere and also fancied some chai. Sitting in the café were even more of Davoud’s relatives, all looked over by his strikingly beautiful café-owner cousin. It was decided that we first had to go and visit his mother and aunts before visiting the windmills. ‘But before that, you should learn some real Parsi! Here, repeat after me!’ There was laughter all around as more tea was ordered.

The next day, we sat in the car with the two Afghan gentlemen, who were then returning home from a round of carpet shopping in Mashhad. As we rocked and rolled across the desert highway, our driver found out I was an archaeology student. This resulted in much excitement in the car, and from then on, he insisted on stopping next to every single pile of old stones, pointing at it and exclaiming, ‘Bastan shenasi! Archaeology!’, looking very pleased with himself. Finally, we arrived in the town of Torbat-e Jam, named after the 12th century Sufi mystic Sheikh Ahmad-e Jami, from whose grave in the mosque courtyard a pistachio tree has sprouted. After a spectacular dinner, and more chai and ghalyan with additional cousins of Davoud’s (‘I have a large family’, he said blankly), we went for a stroll in the mosque courtyard. During the day, the place had been empty, but at night was bustling. A large fire had been lit next to the mystic’s grave, while the silhouette of the pistachio tree flickered against the turquoise-tiled walls of the ivan. A group of Sufis were dancing wildly around the fire, rhythmically chanting and shouting, and, after noticing us, beckoned us to join in. After some wild barefoot laps around the fire, the dazzling mosaics spinning all around us, we collapsed panting in a corner. The spirit of Sheikh Ahmad-e Jami had certainly danced with us that night.

On the road again (courtesy the author)

The next morning, Davoud told us that he first had to call his brother to ask about ‘the situation’. He grinned when he saw the scared look on my face and said, ‘It isn’t the bandits I’m worried about – it’s the holes in the road. My brother drives like mad!’ As we pulled away, it turned out that our newly learnt Persian phrases had been used up rather quickly and Davoud’s brother was a bit shy. The radio didn’t work, but I luckily spotted two cassettes in the car. One contained sung Quran verses, and the other was the soundtrack to David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia. Before we knew it, we were driving along the bumpy road accompanied by a bombastic orchestral fanfare.

A quick stop to ask for directions at one of the eight local tyre dealers revealed we were on the right track. ‘Bebakhshid! Asiyab-badi kojast? Pardon me – where are the windmills?’ There were smiles all around and simultaneous pointing towards my Persian Windmills book and the dusty road in front of us; we were nearly there. As we drove on, I recognised some of the names of places I had read about: Nashtifan. Population: 7,000. Then, they suddenly appeared: a majestic row of about 20 windmills perched on top of a smallish hill. There was no one to be seen. We climbed the steps to the top of the hill and felt the warm 120-day wind (‘breeze’ might perhaps be a better term) on our faces. The desert lay sprawled around us under the sapphire-blue sky. Most of the mills were in bad shape – having probably last ground grain decades ago – and all had been kept still with sticks stuck into their sails. The brake sticks had fallen out of one, which slowly revolved in the breeze that rolled in from the Turkmen plains in the north. I imagined the millers of the past, winnowing and grinding cereal and watching the clouds drift by through the little window in the mill. Flour dust hung in the air as the millstones went round making their gritty sound, and the sails above creaked, spun, and whooshed. In my mind, I saw the dancing Sufis, still dancing about the fire, the spirit of Sheikh Ahmad-e Jami, embodied in the pistachio tree, watching over them and the windmills slowly but steadily working their rounds to supply the villages with much-needed flour.

‘Who are you?’ I awoke suddenly from my windmill reverie and noticed there were two young men standing in front of me, looking quite puzzled. Their white robes flowed in the wind, and they seemed to have suddenly stepped out from a very distant past. It turned out they were simply inviting us over for lunch.

In the 1920s, a Dutch traveller named Maurits Wagenvoort crossed Iran from north to south by camel and wrote a book about it. After almost a year in Iran, as he sailed for Bombay on an English steamer, he saw ‘the grey mountains of Persia gliding away in the haze’ and whispered something in Arabic7. As we bounded along in another disco-taxi back to Mashhad, the mountains of Khorasan faded into the distance. I thought about the two Afghan gentlemen in the taxi. ‘Come with us to Herat! We can drink tea at my grandmother’s house!’ they had said. We sadly had a flight to catch that would take us back to Tehran. Who knows what the future will bring. There are more unexplored windmills just over the border in Afghanistan, and many more in Iran. The Persian adventure was over. Alhamdulillah, I too said, with a little melancholy.

Click here to download this article’s bibliography.