How a handful of Jewish musicians in Turkey have been preserving Ladino’s musical heritage

Over 3,500 kilometres from the Iberian Peninsula – not to mention a temporal separation of half a millennium – Jak Esim, a Sephardic Jew, houses in his Istanbul home what he believes is the most comprehensive archive of Judeo-Spanish folk music in the world. Esim has lived in Istanbul his entire life, but traces his roots to that small landmass jutting into the eastern Atlantic. His native tongue, Judeo-Spanish – or, Ladino – is a dialect of Spanish whose words of Spanish origin have remained frozen in time, a relic of the 1492 Alhambra Decree. Over time, the Ladino of Istanbul’s Sephardic community has also absorbed a number of Turkish words. Esim has witnessed first-hand the decline of Ladino fluency in his community – the size of which is estimated to be around 17,000 – and believes transmitting the tongue through folk music to be the best way of preserving the language. To this end, he has spent the last two decades researching and performing traditional Ladino songs with his wife, the other half of the Janet-Jak Esim Ensemble.

‘I started compiling Ladino folk music from the people around me. I started with my father, grandparents, [and] elderly neighbours’, Esim said when I spoke to him last October. ‘Then, I began researching Judeo-Spanish music full-time, visiting elderly patients in Jewish retirement homes and hospitals. [A few years ago], I realised I had built the world’s foremost Sephardic music archive; other researchers have started to consult with me on this subject!’

The Janet and Jak Esim Ensemble (courtesy Jak Esim)

Influenced in his youth by Esim and Istanbul-based Ladino collective Los Pasharos Sefaradis, Sami Levi has transformed Ladino folk classics into pop hits. Levi’s band, Sefarad – which also included guitarist Ceki Benşuşe and bassist Cem Stamati – has accomplished what many minority musicians have thought impossible: getting crowds of native Turkish speakers to sing along with Ladino lyrics during live performances.

‘I wish I had had the foresight to film some of the concerts and promotional events we did after our first album came out,’ Levi said. ‘I think that footage would have restored people’s faith in humanity. We travelled all across Turkey, and people would chant “Sefarad! Sefarad!” at every event. Turkish people of all ages had memorised the Ladino versions of our songs.’ Their success, though, came not without a compromise: ‘It was obvious to me that we could not have become that popular had we not recorded Turkish versions of all these [Judeo-Spanish folk] songs’.

Representing two different generations of Judeo-Spanish music in Turkey, Esim and Levi’s careers have taken divergent paths. Esim and his wife continue to record Ladino folk songs, and are signed to the independent label Kalan Müzik, which specialises in producing archival-quality albums of the music of Anatolia’s ethnic minorities. Nowadays, the Esim Ensemble occasionally gives small concerts in Istanbul and has also toured Europe to great acclaim.

Sami Levi (courtesy the musician)

Levi, now based in Bursa, has embarked on a solo career and performs primarily in Turkish. Sefarad disbanded in 2007, following what Levi described as the ‘poor performance’ of their third album, Evvel Zaman. When I spoke with him in October, Levi said that while he was not opposed to releasing more Ladino music, he believed that the Turkish-speaking majority had lost interest in a minority language repertoire.

Regardless of the fluctuations in the fan bases of particular artists, it is obvious that so-called ‘minority music’ projects have grown in popularity since the early 1990s, when Kalan Müzik’s founder, Hasan Saltık, pioneered the genre with such ground-breaking acts as the folklore collective Kardeş Türküler (Songs of Fraternity) and Kurdish rock band Grup Yorum. In the past three years, Kardeş Türküler, who have taken their multi-lingual performances around the globe, have shared the stage with the likes of Sezen Aksu, Candan Erçetin, and Şevval Sam. It seems that Turkish music listeners are slowly becoming more aware of the presence of Anatolia’s diverse linguistic and musical heritage.

Hasan Saltık (courtesy HaberTıka)

While Sefarad’s popularity in the early to mid-2000s was an encouraging sign for Anatolian minority artists who wanted to perform in their native tongues, it should also be noted that airtime for any minority language – especially Kurdish dialects – is still almost unheard of on prominent Turkish pop radio stations. Levi himself noted that only Sefarad’s Turkish-language translations of traditional Ladino pieces received airtime – not the original folk songs. Esim, too, admitted that he and his wife had never expected to attain a major domestic following, attributing it to a lack of Turkish interest in Judeo-Spanish culture.

Given the small and ever-shrinking number of Ladino speakers (and, indeed, speakers of Anatolian minority languages in general), the lack of popular interest in Ladino folk music is neither surprising, nor necessarily an indication of Turkish animosity toward Sephardic Jews*; but the fact remains that the multi-lingual cultural heritage of the Ottoman Empire has disappeared, replaced by what many Turks today – including myself – consider to be a singular musical genealogy.

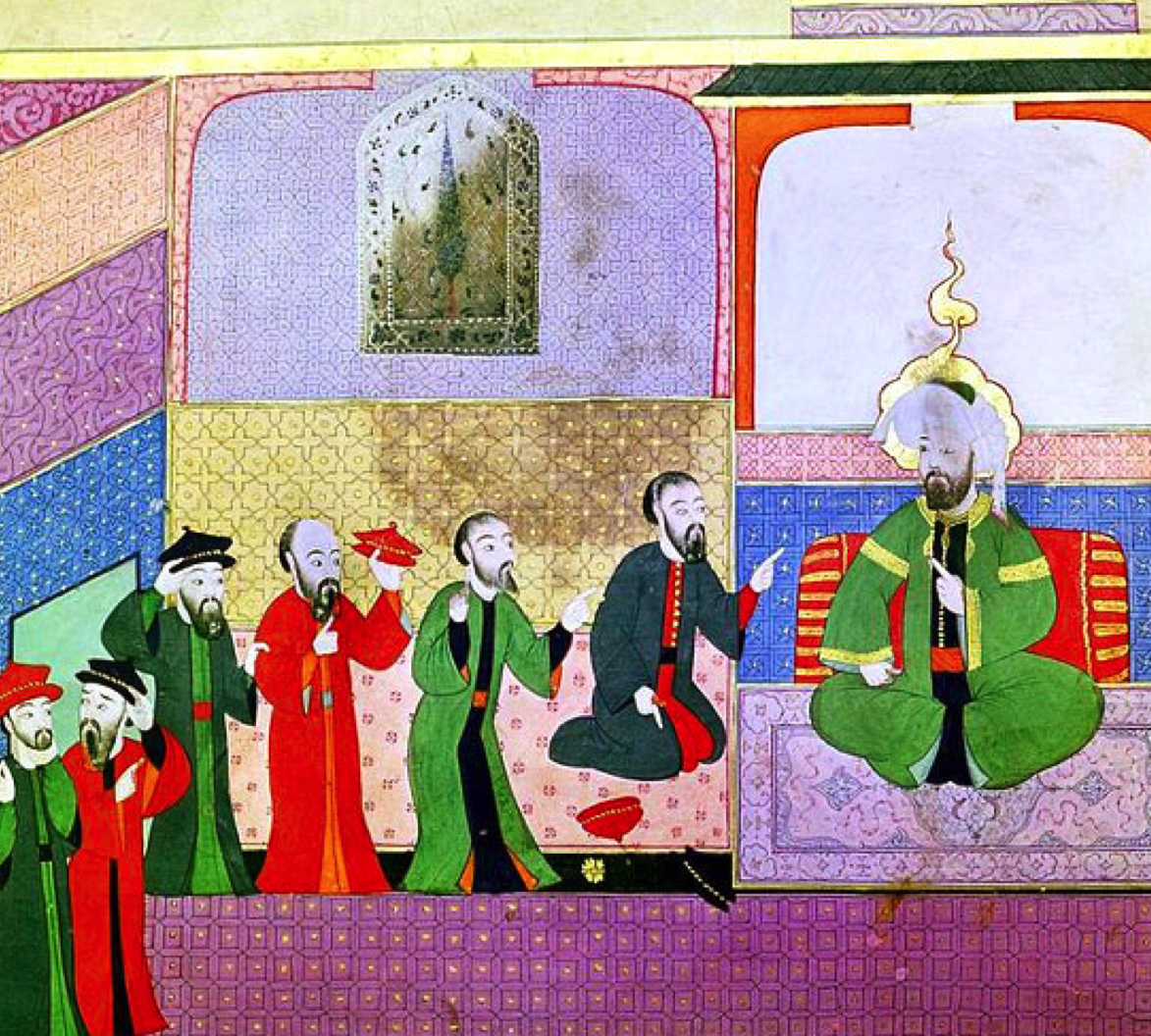

An Ottoman miniature depicting a delegation of Jews meeting with a government official (courtesy the Museum of Turkish Islamic Art in Istanbul)

To understand the origins of this musical historiography, it is necessary to examine how the early Republic downplayed ethnic and religious differences in Anatolia. The Republic of Turkey was established after a four-year war of independence following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. Its Padişah, a Sunni Muslim, wielded absolute power, although numerous top advisors throughout the Empire’s history had been Armenians, Greeks, and Jews, amongst others. In fact, the palace allowed these three communities to govern themselves as millets, or, semi-autonomous nations governed by their own religious laws.

By the beginning of the 20th century, both the non-Muslim millets and the Turks had defined themselves in national terms. The Turkish nationalist movement rejected the millet system, because its adherents believed the minorities ‘were busy … planning the establishment of their own nation-states at the expense of Ottoman territory’1. Ethnic tensions climaxed following the First World War with the Treaty of Sevres in 1920, when the Allies ceded much of Anatolia –which Turkish nationalists perceived as their homeland – to Armenia and Greece. In addition, nationalists in Ankara were dismayed that the non-Muslim elite, including Sephardic Jews, lived in relative prosperity in Istanbul under the Allied occupation.

Subjects of the Ottoman Empire: a Muslim and Jewish woman alongside one from Perlèpè, photographed in Thessaloniki, Greece, in 1873

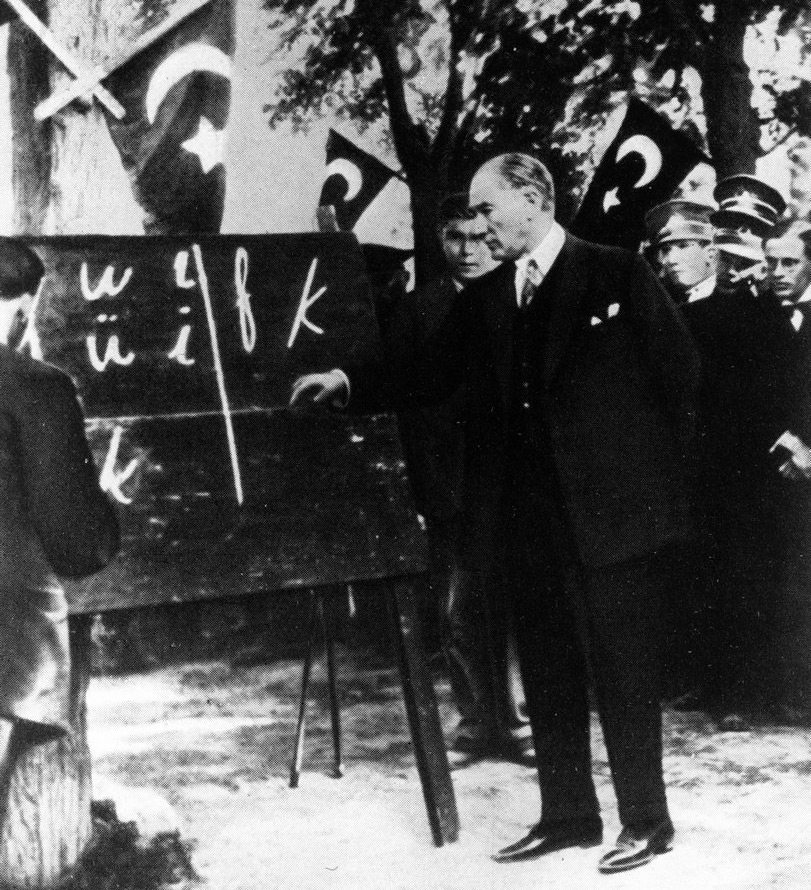

Under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the Republic’s founder, Turkish nationalists expelled occupying forces and re-established control over Asia Minor and Istanbul. In 1923, the Treaty of Lausanne created Turkey’s present-day borders, and Turks once again dominated Anatolia. The new country’s first constitution, ratified by the Grand Assembly in 1924, conferred official minority status upon Jews, Armenians, and Greeks, while also acknowledging that Turkish citizenship applied to people of all ethnicities born within the borders of the Republic of Turkey; but the ‘Turkish’ label still possessed an ethnic dimension: the new state named Turkish the official language, and outlawed instruction in tongues other than those spoken by officially-recognised minorities. The early Republic also set out to build a national culture, to which music was critical. The state banned Ottoman and religious music, while limiting conservatories to ‘teaching government-controlled Westernised’ and ‘Turkified’ folk music2. Radio stations exclusively played Western and government-approved folk music in these early decades, seeking to create a single musical culture by erasing ‘the fact that [Turkish folk music] was a mixture of different ethnic and religious cultures that had lived together for centuries’3.

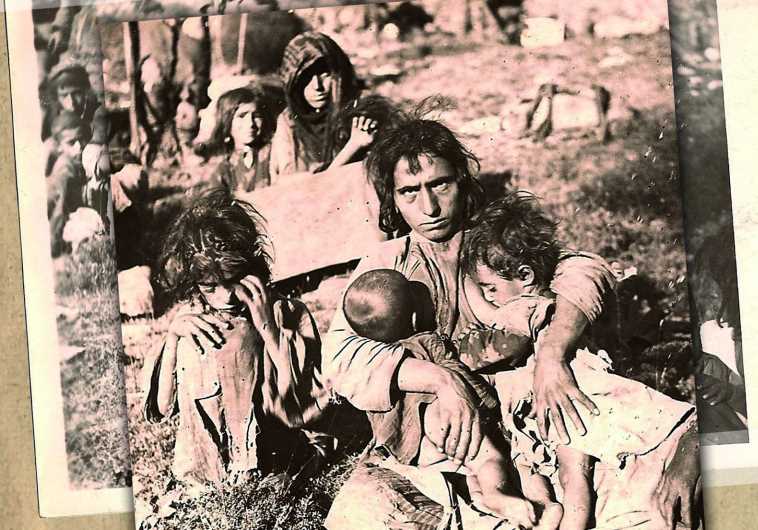

Greeks fleeing Turkey from Smyrna (Tr. Izmir) during the Greco-Turkish War (1919 - 1922) (courtesy Topical Press Agency/Getty Images)

Sephardic Jews had called Anatolia home since 1492, the year they were expelled from the Iberian Peninsula and admitted to the Ottoman Empire by the thousands. Jewish-Turkish historian Rıfat Bali wrote in his seminal work Turkish Jews in the Republican Era, that Jews were still made to feel like ‘guests’ rather than natural-born citizens in the early years of the Republic; often, when a Jew appealed the denial of his request to serve in the military or bureaucracy, the authorities would remind him that his kin ‘owed a debt’ to the Turkish people. In addition, Bali wrote that many Turks believed the non-Muslim minorities living in Istanbul were avoiding a ‘blood payment’ (kan bedeli) during the War for Independence, although in reality, many Jews had fought alongside Muslims4.

By the 1960s, Turkish had become the mother tongue of most of the nation’s Jews … By the 1970s, most Jews in Turkey considered Ladino to be ‘a deformed mixture of languages’ not worth teaching their children

Language became another serious point of contention. While the constitution allowed Jews to educate their children in Hebrew and Ladino, Hebrew was reserved for the elite Jewish clergy, while Ladino was rarely encountered outside homes. In fact, most Jewish schools offered a French curriculum, but the Turkish state would not permit instruction in French, as it was not a strictly-Jewish language5. This, combined with the growing popularity of the Vatandaş Türkçe Konuş! movement (‘Citizen, Speak Turkish!’), prompted Jewish community leaders to educate their children in Turkish for the first time in nearly 500 years6. Ladino still dominated Jewish domestic life, but as Jewish-Turkish scholar Mahir Şaul wrote, the new generation spoke ‘Turkish not only correctly, but also without the peculiar Jewish accent’. By the 1960s, Turkish had become the mother tongue of most of the nation’s Jews. In a study of Jewish-Turkish youth, Karen Şarhon found that by the 1970s, most Jews in Turkey considered Ladino to be ‘a deformed mixture of languages’ not worth teaching their children.

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk teaching schoolchildren in Kayseri the Latin letters of the newly reformed Turkish alphabet (1928)

After nearly seven decades of assimilationist policies, the 1990s brought new opportunities for minorities to reclaim their non-Muslim and non-Turkish heritage. It was a decade of turning outward; in 1991, the government reversed the 1980s ban on releasing music in ‘languages without a flag’, referring to the mother tongues of many of Turkey’s ethnic minorities7. Unthinkable in prior decades, Foreign Affairs Minister Ismail Cem gave his Swedish counterpart a collection of albums by Kardeş Türküler at the 1999 EU accession talks8; but the 1990s were also the worst decade of fighting between the Turkish military and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). The conflict seeped into popular culture and heightened ethnic tensions outside of the battlegrounds in eastern Turkey. During this time, police in Kurdish-majority provinces were known to confiscate Kurdish-language cassette tapes9.

Kurds in 1938 during the Dersim massacres (courtesy the Jerusalem Post)

In this decade of stop-and-go multiculturalism, Hasan Saltık built a record label that attempted to make the ‘Turkish folk music’ genre encompass a greater number of indigenous musical traditions. Saltık founded Kalan Müzik in 1991 to document the ‘Anatolian cultures to which the [Turkish] music industry had never paid any attention’10. Both the Esim Ensemble and Sefarad emerged in this period, although for very different reasons. Jak Esim, Kalan Müzik’s most prominent Judeo-Spanish artist, launched his folk career in Istanbul in 1985 after playing classical music in various ‘European-style’ orchestras as a teenager. He told me he felt compelled to make the transition because, after spending his early childhood immersed in the Ladino language, he felt his connection to his Judeo-Spanish heritage was weakening. ‘I thought I should learn about ethnic music, the music of our community,’ Esim said. ‘I had learned both [Turkish and Ladino] at the same time as a child. In fact, I was more comfortable speaking Ladino. That all changed when I started going to [Turkish] primary school.’

The cover of a 1929 issue of the bi-weekly Ladino-language newspaper La Boz de Türkiye (The Voice of Turkey)

Esim began interviewing and recording elderly Sephardic Jews all around Istanbul, beginning with his immediate family. Fikret Kızılok, a pioneer of Turkish rock who also released several albums through Kalan, hosted Esim at Çekirdek Sanat Evi, which Esim said might have been the first-ever public performance of traditional Judeo-Spanish music in front of an ethnic Turkish audience. After a few years of playing Ladino folk songs as a solo act, Esim formed the Janet-Jak Esim Ensemble with his wife in 1989, the same year the duo released their first album, Antik Bir Hüzün: Judeo-Espanyol Ezgiler (An Ancient Melancholy: Judeo-Spanish Melodies). Their next album, Sefaradim I, coincided with the 500th anniversary of the Alhambra Decree. Riding the wave of media attention both domestically and abroad, the Esim Ensemble played major venues in Turkey, as well as in Western Europe.

Despite the Ensemble’s following abroad, Esim says the group has never been able to attract comparable crowds to their shows in Turkey. ‘We’ve never targeted a particular demographic or audience,’ Esim said. ‘Our only concern has been to produce quality music, interesting music. There is a certain kind of crowd that’s interested in our kind of music at international venues, but we were never able to recreate that environment here in Turkey.’ Moreover, Esim believes that minority artists in Turkey still face public backlash when performing in their languages at smaller concert venues. On one occasion, he witnessed a singer performing over the sound of ultra-nationalist chants at a festival taking place on Heybeliada, one of the Princes’ Islands located in the Sea of Marmara off the coast of Istanbul. ‘You’re unlikely to run into any problems if you’re just recording an album in an ethnic language,’ Esim said. ‘But I’m still afraid to take the stage and sing in [a minority language] in certain contexts. Fortunately, if you perform in large urban venues, you won’t really run into the same problems … We are making ethnic music, and we need to be mindful of certain risks.’

Sami Levi started to explore his ancestors’ musical traditions a decade after Esim began his research, and Levi’s experiences with Ladino music have been markedly different. While Levi had also grown up hearing his parents and grandparents sing Judeo-Spanish music at home, Ladino remained foreign to him until late in his adolescence. ‘My late grandmother spoke Spanish very well, but I never learned Ladino as a child,’ Levi mentioned. ‘My family harboured this “minority mentality” (azınlık psikolojisi) that kept us from speaking Ladino at home. I learned it in small doses. At this moment, I can’t say that I can speak it fluently.’

Although Ladino would not become Levi’s mother tongue, he said that he was never afraid to speak openly about his Jewish heritage, despite often being the only Jewish student in his public school classes. ‘People always ask me if my first name is pronounced Saa-mi (consistent with Turkish pronunciation) or Sa-mi,’ Levi remarked. ‘I’ve always told them, “Sa-mi”, even when I was attending public schools with Muslim Turks. And I was never afraid to tell my classmates that I was Jewish, because I was so confident in my Turkish [identity]. I love my country. My family has been here for at least five, six generations.’ But unlike Esim, who was drawn to Judeo-Spanish music by a desire to learn more about his heritage, Levi’s Ladino journey originated in a desire to perform. ‘My earliest memories are of the “concerts” I would give to my family in the living room,’ Levi remembered. ‘I always wanted to be an artist. When I got older, I told my friends [Stamati and Benşuşe] about these [Judeo-Spanish] songs, [and how] we could arrange them so that they would become pop hits,’ he said. ‘To be honest, our goal wasn’t to introduce Sephardic culture to the rest of Turkey; we just wanted to be famous. But it was to our benefit that one of the Ladino songs on our first album, Osman Ağa, had a very well-known Turkish version.’

With its synthesis of Turkish and Ladino lyrics, Balkan-influenced brass rhythms, and Western pop sensibilities, the band’s 2003 debut album, Sefarad, dominated airwaves and music video platforms for months. Unlike the Esim Ensemble, which was signed to independent folk music labels prior to releasing its 2006 album, Adio, through Kalan, Sefarad signed with Doğan Müzik Yapım, joining a roster of prominent Turkish pop acts. The group followed up their breakout success with 2005’s Sefarad II. Their third album, released in 2007, also featured songs in both Ladino and Turkish – but pop music fans’ interest in Judeo-Spanish music had already evaporated by the time Evvel Zamanlar hit music stands, according to Levi.

‘From a purely commercial standpoint, Sefarad could not go on,’ Levi said. ‘We had already recorded and performed the most marketable Judeo-Spanish pieces. If our whole intention for the group had been to research and promote Sephardic music,’ he explained, ‘then we might [have] still [been] a band – but we’d probably be touring cultural festivals around the world instead of playing shows in Turkey … We chose the latter.’ After Sefarad disbanded in 2007, Levi debuted as a solo artist with Hade Hade Duke Duke, an album featuring Judeo-Spanish melodies with Turkish lyrics. Now living and performing in Bursa, Levi’s repertoire primarily consists of Turkish-language pop pieces. Although he still enjoys singing in Ladino, he says he is ‘an artist, not a missionary’, and that promoting Judeo-Spanish music is not his primary focus.

For the time being, it seems that exposure through conventional music channels will require minority artists to release Turkish-language songs. Dozens of artists of Armenian, Jewish, Kurdish, and Greek descent have enjoyed mainstream success with Turkish-language albums. By the same token, Kurdish artists like Aynur Doğan and Rojin have sold thousands of albums and tickets to concerts in Turkey featuring songs in Kurdish. For folk musicians like Jak Esim, however, whose Judeo-Spanish community is amongst the smallest in Turkey, simply having raised some awareness of their musical heritage on the global stage is a success in and of itself.

Levi, too, feels lucky to have been able to explore multiple facets of his identity through music. ‘Someone once asked me what comes to mind when I hear the word “Turkey”, and how I would describe myself and my origins,’ he said. ‘I told him that I would describe myself as both a Westerner and an Easterner, a child of the Aegean and Black Seas. And even if Turkey changes, Anatolia will always be there. So maybe I should have said that I’d describe myself as Anatolian.’

Click here to download this article’s bibliography.

* It should be noted that the marginalisation of Kurdish dialects in 20th century Turkish music was a direct result of assimilationist policies enacted over several decades; these are beyond the scope of this article, although a very important part of the history of modern Turkish music.

Cover image: a detail of a photograph of a Sephardic couple in Sarajevo (1900).