Cigarettes, coffee, and controversy - chatting with Lebanese rebel filmmaker Danielle Arbid

I was attending a documentary film festival at the Pompidou Centre in Paris, where Danielle Arbid had just screened her latest experimental short, Allo Chérie (Hello Dear, 2015). In it, moving imagery of random streets in Beirut – shot using an iPhone – are set to audio bits of phone conversations between the filmmaker’s mother and shady, predominantly male ‘business partners’. Throughout the projection, the audience seemed perplexed, but thoroughly enlivened by Arbid’s mother and her vigorously active logorrhoea. When the time came for the Q&A segment, most of the attendees chose to toss platitudes left and right. The turn of an older woman came, who seemed eager to get a staff member to lend her the microphone. At first, Arbid appeared measured and steely as she took in the woman’s question. Upon closer inspection, though, and, as the question spread itself painfully in time, some of her facial features betrayed her calm demeanour. Prior to our first meeting, fellow journalists had warned me of the filmmaker’s volatile nature, but I instantly ruled them out as misogynistic. My general impression was that she was self-possessed, warm, and also surprisingly generous; but at that particular moment, it felt like she was ready to explode. The dynamic was tense, bordering on grotesque. The woman’s closing remark – and the moment her rhetoric finally espoused the seemingly ever-impending interrogation mark – was especially distressing. ‘I can’t seem to figure out what it is you’re trying to say about Lebanon and its people. I mean, are even trying to say anything at all?’

Had she voiced an opinion on the experimental short’s depiction of the maternal figure, even if to delineate its shortcomings or ethical botheration (the way most other members of the audience chose to), I doubt that Arbid would have minded. For instance, when a critic asked, ‘Aren’t you being a little rough on your mother by portraying her as a smalltime crook?’, she replied, laughingly, ‘I’m not going to distort the truth for the sake of phony romanticisation. My mother is a smalltime crook, and that particular element shapes her entire personality’. But to mention Arbid’s native Lebanon – and to implicitly accuse her of not being a worthy ‘ambassador’ – was perhaps exceeding acceptable limits. Following a full minute dominated by an awkward silence, the filmmaker scathingly addressed what she perceived as an indictment. ‘When you hail from Lebanon – or the godforsaken Middle East in general, for that matter – the “us” always finds a way to smash the “I”. Thank you for reminding me of that.’

A still from Parisienne

This quote can be better understood when faced with the evidence that Lebanon has hardly granted Arbid the sort of esteem it has been known to award, say, other Lebanese talents, such as the globally renowned filmmaker Nadine Labaki, or public darling Philippe Aractingi. Out of the four feature films Arbid has directed, one of them, Dans les Champs de Bataille (In the Battlefields, 2004), was heavily censored, while two others – Un Homme Perdu (A Lost Man, 2007) and Beirut Hotel (2010) – were banned from theatres on the grounds of depicting ‘overt sexual content’ and threatening ‘national security’, as stated by the country’s Censorship Bureau. As well, the country’s cultural elite also abandoned Arbid as she chose to, in her own words, ‘defy the system’ by taking legal action against what she regarded as the unfair censorship of her films. Most local journalists and critics opted to judge her films through the prism of a sermonising moralism, so tied with notions of national representation that their words amounted to a negative partiality. Vast amounts of ink were spent condemning the ‘erotic’ nature of her films, and what many perceived to be ‘problematic’ depictions of Lebanon in them. By the time the news leaked regarding the ban on Beirut Hotel, the sheer toxicity of the critiques pointing in Arbid’s way had become so intolerable that she decided to permanently move to Paris.

I’d been meaning to ask Arbid questions pertaining to her relationship with Lebanon for a while. I thought her latest film, Parisienne (Parisian, 2016), a semi-autobiographical account of a young Lebanese student having to fend for herself in the French capital, would provide me with some answers. The film in itself largely convinced me of the reasons why she had chosen to make Paris her new home. While it conveyed all the ‘yearning to breathe free’ emotions that Arbid attaches to Beirut, it failed to quench my curiosity with regard to the reasons – the real reasons – why she went into self-imposed exile. After all, to reduce the filmmaker’s tumultuous rapport with her country to her complications with the authorities and the press would be to unjustly disregard the counter-narratives she has chosen to champion in portraying Lebanon.

A still from Beirut Hotel

We first met at an early hour in a café located near Paris’ Gare du Nord train station. Parisienne had just come out, and French critics were raving about her poetic spin on clichéd coming-of-age tropes. I instantly asked her about the way she had portrayed Beirut previously. The malaise that haunts every single shot she’d taken of the city throughout her oeuvre could have probably attested to her detestation of it, but I wanted her to elaborate. ‘Look – when I’m there, I’m constantly afraid. I’m afraid they’re going to kill me’, she remarked, going on to say that:

This fear is deeply rooted in my childhood. I would sleep next to my father, and he’d always have a loaded gun next to his pillow. I used to worry that he would kill me in the middle of the night, while the enemy was slaughtering my people at the height of the Civil War. It’s an unexplainable fear, really; it’s devoid of any logic, since my father loved me and would never have done that to me. This feeling of absolute insecurity, this fear – most Beirutis often choose to ignore it. Either that, or they get hooked on it; it keeps them going like a drug. I’ve come to reject it, firmly. It tires me, even though at one point in my career, it became my primary source of inspiration.

A still from Seule avec la Guerre

The notion of fear, in all its complexity and banality, organically includes itself within Arbid’s narratives. The questions that arise from them turn on continuity and discontinuity, on whether or not to judge a given development in a storyline as a ‘break’ from what preceded it, and whether or not to perceive a given fear as ‘legitimate’, or as a product of both individual and collective paranoia. ‘I am obsessed with the idea of capturing the intangible with my camera. I’ve always wanted to speak the language of our paranoia as inhabitants of Beirut’, she said. In order to successfully transcribe the language of this collective paranoia, Arbid had to first concretise – through cinematic language – the Lebanese people’s understanding of the past, and their projections of the future. This allowed her to seek out that which she had been aspiring towards: solace. In her 2000 documentary Seule avec la Guerre (Alone with War), she confronts some participants of the Civil War about their involvement. She initiated a quest for preserving memories after having seen how forgetfulness, as an expression of collective amnesia, led to denial and the dangers of historical revisionism. In the film, Arbid’s participants refuse to take the blame for anything. As it progresses, she appears more and more impatient. In the case of this particular film, solace could never be reached, arguably. Afterwards, she chose to give up on proposing any alternative to the circumstances to which she had been opposed – which partly explains her entry into fiction filmmaking.

A still from Dans les Champs de Bataille

Dans les Champs de Bataille, her first feature film, tells the story of rebellious and neglected 12 year-old Lina, the daughter of self-destructive parents, who don’t show much interest in the war taking place around her in Beirut. Instead, Siham, her aunt’s sensual domestic worker, is the focal point of Lina’s internal dialogue and desires. Mockingly subversive and cruel, Dans les Champs de Bataille mounts a frontal assault on the institution of family in a way that is reminiscent of Marco Bellochio’s ferocious 1965 film, I Pugni in Tasca (Fists in the Pocket). Arbid masterfully parallels Lebanon’s socioeconomic unrest with the unravelling of a domestic conflict inside a middle-class apartment building in Beirut. There is no emphasis on the ‘general’ or the ‘sociological’ amidst regional calls for grand narratives – which the filmmaker inherently rejects – but instead, an insistence on the need to link personal retellings, power structures, and culture to explore the full articulation of subjectivity, which brought Arbid to cinema in the first place:

I started out as a journalist, and became increasingly disgusted with the profession, because I felt like it was violently trying to suppress my subjectivity. Cinema came to me out of nowhere. My attraction to it wasn’t that of a cinephile – it was purely unconscious. On my very first set, and when I discovered what I was truly able to do – that is, create a narrative using my own eyes as a starting point – the feeling was similar to that of a believer witnessing a revelation from the Virgin Mary herself. Throughout my career, I did exactly what I was asked not to do as a journalist: I refused to erase myself.

A still from Dans les Champs de Bataille

She told me this after taking a sip of her third coffee, watching me over the rim of her cup with an amused expression. ‘I once had an actor I was working with, who spent his time off set telling people I wasn’t professional’, she recounted. ‘Actually, he’s right – I’m not. If I had wanted to be professional, I’d have stuck to journalism. I’m instinctive, impulsive, and hotheaded.’ Arbid told me that her aim wasn’t to produce content, but instead what she called a ‘raw form of subjectivity’. ‘Let’s not kid ourselves – I’m no Fassbinder. I require that each of my films be infused with a maximum amount of ardency, in essence, form, or method’.

Arbid’s films … are courageous explorations of a dying city, sumptuous (and often cruel) frescoes of decadent inhabitants seeking to recover lost certainties and prejudices in an occasionally somber, yet consistently ironic form of desperation

When Un Homme Perdu was first shown across international film festivals, it set off shockwaves across the Arab world, and was subsequently banned in most of the region. In the film, a French photographer named Thomas embarks on a journey to Jordan and Lebanon to have sexual encounters with local prostitutes. Along the way, he meets a Lebanese man, Fouad, who can’t recall his own past and eventually befriends him. Arbid said that the film was mainly about ‘getting lost’. It thrives on vagueness and the suffocating spectre of an imminent threat that seems to haunt Amman and Beirut. ‘I was obsessed with the image of a foreigner wandering aimlessly in the streets of Beirut’, she told me. ‘I was inspired by William Vollman’s brilliant writings on Iraq and Syria, but also by the personal experiences recounted to me by the French photographer Antoine d’Agata, whose picture of a naked woman in Gaza I had once seen pushed me to write the screenplay.’ In one scene, Thomas takes out his camera while having sex with a prostitute in a seedy hotel room in Amman. In another, Fouad is making out with a woman at the border between Syria and Jordan, while Thomas snaps pictures of the two in action. Some critics were quick to point out the film’s ‘anti-colonial’ subtext, which Arbid dismissed as lazy faux-analyses. ‘My end goal was to challenge representations of sexual behavior in Middle Eastern countries and make the Arab female body desirable’, she explained. ‘Sexualising Arab women isn’t perceived as politically correct nowadays, but I insisted on doing so … Even in Beirut Hotel, I was desperate to show that Arab women could be subjects of desire, [and] even love.’

A still from Un Homme Perdu

Beirut Hotel first began as a side project for the French public television network ARTE, a B-noir à la 80s De Palma about Mahtieu, a French lawyer who gets involved with Zoha, a charming but utterly naïve Lebanese club singer. Not unlike Un Homme Perdu, Beirut Hotel is filled with scenes set in Beirut replete with a sense of disembodied dread. The presence of political undertones in the screenplay simply serves as an addition to the various cinematic techniques employed by Arbid to instill feelings of anxiety, paranoia, and fear. For instance, at one point, Mathieu becomes embroiled in a scheme that aims to uncover the names of people involved in the assassination of the former Lebanese prime minister Rafik Hariri. Ultimately, Lebanon’s General Directorate of General Security saw in the film’s political rhetoric a ‘threat to national security’, which led to its banning in the country.

It was expected that Beirut Hotel would raise a few eyebrows. Arbid’s films – at least the ones shot in Beirut – are courageous explorations of a dying city, sumptuous (and often cruel) frescoes of decadent inhabitants seeking to recover lost certainties and prejudices in an occasionally somber, yet consistently ironic form of desperation. There is an underlying refusal to succumb to the ‘neo-Orientalist’ gaze – as described by the Lebanese film scholar Wissam Mouawad in his critique of Labaki’s Where Do We Go Now? – which local filmmakers often do in depicting Lebanon. The country’s limitation on individual creativity and lack of engagement in critical discourse has systematically led to boxing local artists as either worthy ‘national ambassadors’ or blasphemous troublemakers out to tarnish the reputation of the Land of the Cedars. Today, Arbid somehow feels proud to belong to the latter category. ‘It’s not like I’m intentionally trying to piss on my country, even though reactionaries consistently accuse me of doing so’, she remarked, adding that:

If my films are seen as an assault, if they pull back Lebanese audiences to their everyday realities, it means I’ve succeeded in my mission. I am happy to belong to the Arab world, but I’m neither its object, nor its official spokesperson. To depict Lebanon in an imperfect light goes against every single principle of appropriateness we were force-fed as a people; but to me, Lebanon has never felt like Disneyland, and I won’t cede to calls demanding I don’t highlight that feeling.

A still from Beirut Hotel

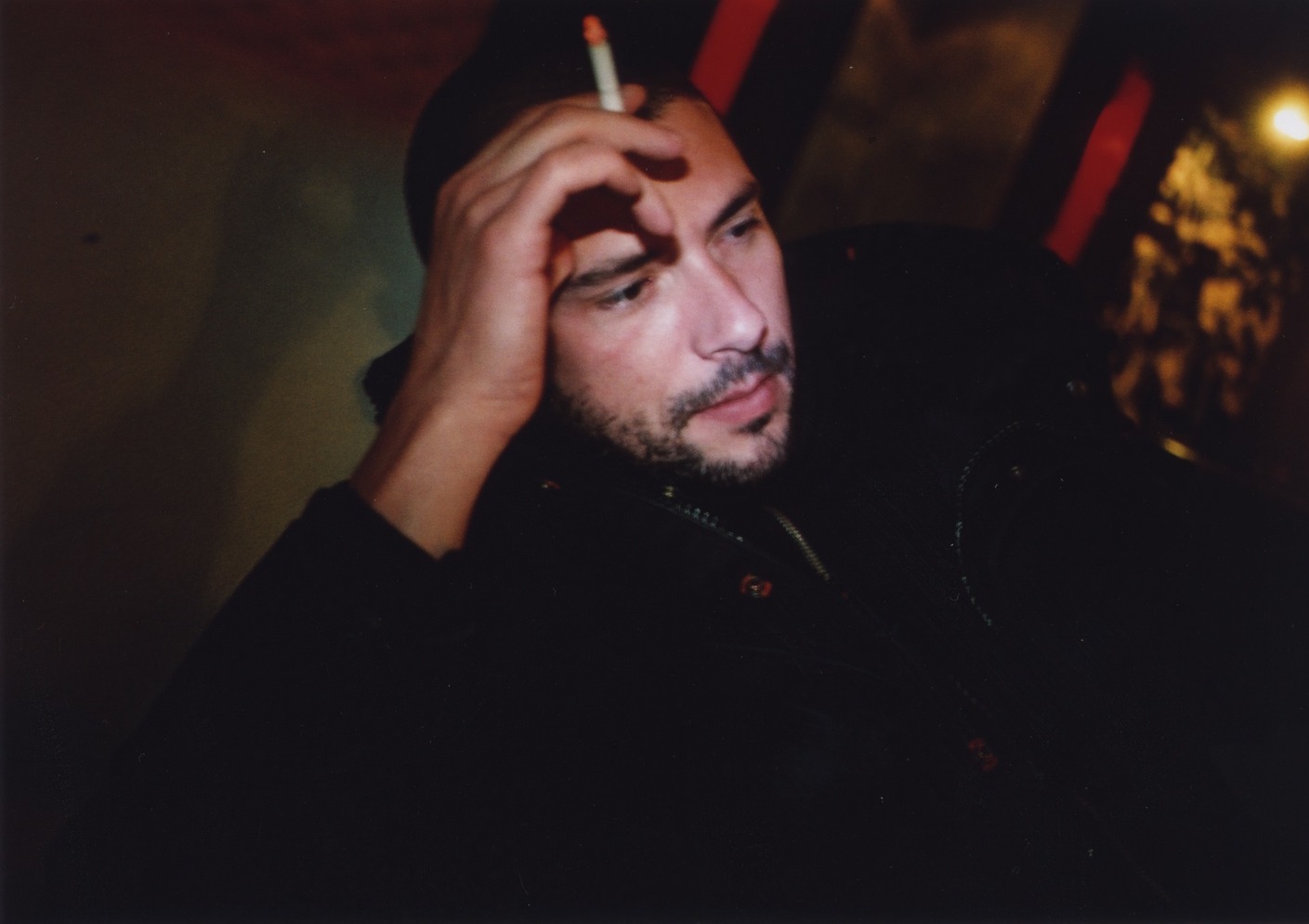

Following that statement, Arbid and I went outside to smoke. It was clear that all the talk about Lebanon had exhausted her. In-between two puffs, I let her know that upon viewing Parisienne, I was startled to discover that most of her rage, fear, and confusion had withered away. The shaky camera work, murky settings, and overbearing, vicious figures were traded in for Truffaldian flânerie. Lina, her main character, was still boldly fighting for self-affirmation, but was doing so with an infectious smile. Even though Arbid refused to call the film autobiographical, one can’t help but deduce that she herself – perhaps even more than Lina – has finally found solace. Is it because of her physical distance from Lebanon? Perhaps.