Dreaming, scheming, never growing old: remembering Abbas Kiarostami (1940 - 2016)

I was only too happy to be leaving Prague; it’s not exactly my kind of place. At the same time, I wasn’t particularly looking forward to the nosebleed flight to the other end of the world awaiting me. What on earth was I doing there, anyway? Even I didn’t know. The damned pink walls of my hotel room were beginning to curse me, and the AC had long before done a number on me. I awoke with a burning throat at around a quarter to three in the morning, not hearing a sound on the cobblestone streets below, draped in deepest black. Not even a hot shower could bring me to my senses, and, after awkwardly slipping on my black jeans (why do I always bring so many pairs when I only ever wear one?), I flicked on the television out of utter boredom. I was expecting the usual: Brexit, Baghdad, Dhaka, Medina, ISIS here, ISIS there. What a week, I thought to myself, as I coolly flipped through the channels before my thumb stopped clicking.

There was no mistaking those shades, that equanimity. No news is good news, and all news is bad news. Kiarostami has gone, too. I was thinking in Persian, on the verge of waxing sentimental; yet, I felt numb, just as I did when I’d heard about the attacks of the past week. I wanted to feel an outpouring of emotion, a pang, a shiver – something. No matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t find anything within, save a gaping hollow. Was it because I’d grown indifferent to death, or simply because I was no longer the child who’d once thought his heroes immortal? Death for me used to be an event, a spectacle; I’d be stunned for days, trying to make sense of everything. My world was quieter as a boy, and such untimely demises left a mark of some kind, no matter how small. Now, it seems as if they’re just headlines, other pieces of news for journalists to scramble over like a pack of rabid dogs. For whatever reason, I remembered another one of my heroes, the Persian mystic Attar of Neyshapur, and his sheer indifference at his death at the hands of the Mongols. A disdain for the faithless wheel of heaven aside, I wondered then whether it was the twenty-first century or the thirteenth. The hordes of Hulagu could have been sweeping through Bohemia at that very moment, and I wouldn’t have so much as batted an eyelash.

All I knew then was that a part of Iran had died, and in turn, a part of me. What a week, I kept saying to myself, over and over again, trying to ignore the Czech pop songs buzzing on the taxi radio on the way to the airport.

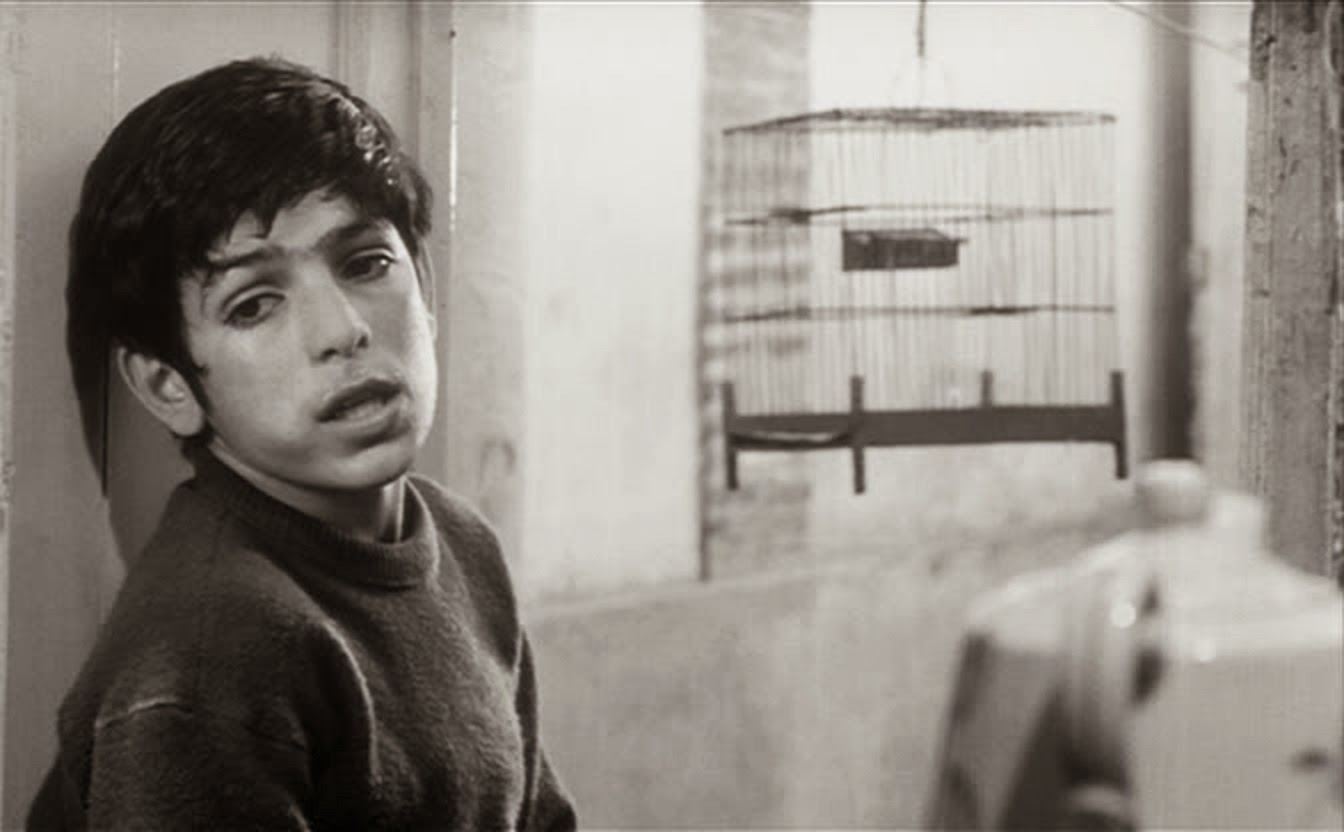

A still from Nama-ye Nazdik (Close-Up, 1990)

I didn’t grow up with Kiarostami’s films. I discovered Abbas Kiarostami long after he’d become Kiarostami, during the same time that I began devouring everything having to do with Iranian culture. I vaguely remember visiting the Film Museum off of Vali-ye Asr Avenue in Tehran with my friend one hot summer’s day, when I was around sixteen years old. I had no idea who the man in the sunglasses was, only that he was of significance where Iranian cinema was concerned. To people like my friend (a film buff now working in the industry in Iran), directors like Kiarostami, Mohsen Makhmalbaf, and Dariush Mehrjui were demigods, not mere mortals; they had set the gold standard for Iranian art house cinema, and all and sundry took their cues from them. I remember hearing Kiarostami’s name more than anyone else’s though; it was he, apparently, who headed the pantheon of Iran’s great post-Revolution directors. It therefore only seemed natural that, when beginning my foray into the seemingly endless ocean of Iranian cinema, I’d begin with his films. I hadn’t a clue what I was doing, but as long as Kiarostami’s name was on the tin, I knew I was in good company.

A still from Zendegi va Digar Hich (Life, and Nothing More, 1992)

Some years later, as a second-year university student in Toronto, I would stock up on all kinds of Iranian films – black-and-white classics, Film-Farsi, masterpieces, and outright trash. It didn’t matter what the subject was; as long as the film had to do with Iran, I was interested. I can’t remember most of what I watched; as I’m writing now, images are passing by my eyes in a blur. Gheysar was, and always will be my all-time favourite film, but I also vividly recall the works of Kiarostami. I began with the titles with which he rose to international fame, and worked my way backwards. The classic Khaneh-ye Doost Kojast? (Where is the Friend’s Home?) and Ta’m-e Gilas (Taste of Cherry) were my first introductions to his art and philosophy. Admittedly, his signature extended shots of figures slowly receding into the distance tried my patience as a teenager, but for some reason, I nonetheless felt myself continuously drawn to the pictures he would paint. I wasn’t watching art house cinema for the sake of it, or to have something clever to say at a cocktail party, but rather to learn more about my country, my language, and my people. Watching Kiarostami’s films, I felt as if I actually were in northern Iran, walking alongside his innocent children, or in the backseat of a Paykan on the squalid streets of Tehran. As with the earlier films of Jafar Panahi, what at first struck me the most was Kiarostami’s brazen honesty: he wasn’t sensationalising or criticising (openly, at least) anything – he was telling it like it was. I saw his films not as spectacles, but – recalling the earliest definition of films – moving pictures that afforded me, one who had always looked at his motherland from afar, a glimpse of what it meant to be Iranian. If Ferdowsi had nailed it with the Shahnameh (Book of Kings), his thirty-year-long labour of love and paean to Iran, Kiarostami, perhaps, achieved the same behind his camera, centuries later.

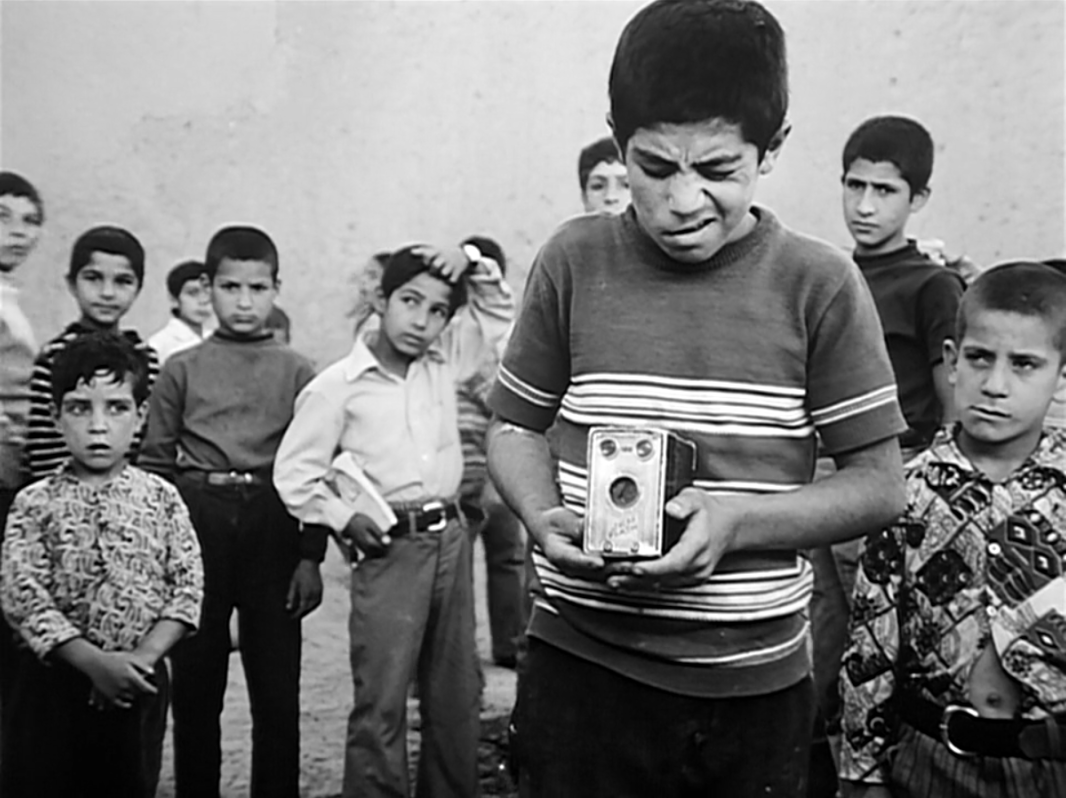

A still from Khaneh-ye Doost Kojast? (Where is the Friend’s Home? 1987)

As a student, I used to watch Kiarostami’s films on and off. I admired them, but never considered myself an ardent follower, unlike a Korean professor of mine. Things took a turn, however, when I somehow discovered his early pre-Revolution films, which he had made for the Centre for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults. Watching Mosafer (The Traveller), Lebas-i Barayeh Aroosi (A Wedding Suit), Zang-e Tafrih (Breaktime), and Nan va Kucheh (Bread and Alley) was love at first sight. The cinematography wasn’t as refined, and they didn’t carry messages as weighty as those in the Palme d’Or-winning Taste of Cherry, but they spoke to me more than any of his other films, no matter how many awards they’d won. For the first time, I felt myself caring for the characters in a film; I could empathise with them. I inherited their joys, fears, and sorrows, and all the excitement of a naughty boy looking for a bit of fun in the big city. My heart sank during the final scene of The Traveller, in which Kiarostami’s boy hero (who else?) saw all his dreams and schemes to attend a football match in Tehran amount to naught, as all those little stubs fluttered about in the wind; and, watching A Wedding Suit, I couldn’t help but remember all the times I’d looked at my father’s closet in awe, trying on his clothes and never minding that his blazers were three sizes too big for me. I loved those little boys, for whom I’d cheer behind my television screen. I wanted to tell them to ditch their thoughts of homework and grown-ups, and to stay forever young – exactly like the director himself.

A still from Mosafer (The Traveller, 1974)

I’ve never cared much for eulogies; I fail to take them seriously or assign a modicum of honesty to their authors. Call me a pessimist, a sceptic, whatever. I haven’t read any of the tributes to Kiarostami yet, but I have glossed over some of the titles being attributed to him: ‘Father of Iranian Cinema’, ‘genius’, ‘one of the world’s greatest directors’. I’ll leave such things to the critics. I always regarded Kiarostami as someone to look up to not because he was a great director (as I said, I never watched his films for the sake of great cinema), but– more than anything else – because he saw the world through the eyes of a child. If his films became somewhat more ‘weighty’ with time, it was only because Kiarostami had grown wiser with age – not older. While he was known for his use of non-professional child actors who barely knew him, the subject of children extended far beyond the surface of his craft. I wasn’t only witnessing children running about, trying to give back their friends’ notebooks before the next school day or playing hooky; I was thinking like a child, wandering like a child, relishing the simplest pleasures of life with unparalleled pleasure like a child, and shivering in my little trousers like one. That the child in Kiarostami continued to live on and dream, rather than be quelled by the passing of time and the death of innocence is, to me, his greatest feat bar none. Just as I love my rock and roll stars because they never grew up, so too do I love artists like Kiarostami. Marc Bolan, Antoine Saint-Exupéry, Abbas Kiarostami – they are all but variations on a theme, the starry-eyed brethren of the Lost Boys.

A still from Lebas-i Barayeh Aroosi (A Wedding Suit, 1976)

When I was told Kiarostami was in town last November, I didn’t know what to think. I’ve always been wary of meeting those whom I admire, as I never know whether or not they’ll live up to the images I’ve conjured in my head. My first thought is usually that they’ll turn out to be assholes. As well, I don’t ever have anything to say to such people, either. I mean, what would I say to him? I thought at the time. Love your films, mister? Or, like someone I once knew had said to Rod Stewart upon bumping into him in a hotel elevator, ‘You’re doing a good job’? What does one say in such situations? I certainly didn’t want to spew out proverbial Persian sweet-nothings or try to affect the airs of a savant. I even thought for a moment that it would be better if I skipped the event altogether. I’m glad, for once, I didn’t.

… With his childlike heart and soul, [Kiarostami] reminded me of the overwhelming beauty of life which can always be ours and is always waiting to be beheld by our eyes – if only we open them

I was due to meet a friend at a talk by Kiarostami at the headquarters of the Toronto International Film Festival downtown, and he’d requested I bring him some copies of my magazine. Afterwards, I handed my friend the magazines I’d brought along and said I’d be heading home. He wanted me to meet Kiarostami, but, perhaps after being hounded by fans inside the theatre who kept asking him if he could remember them, the man in black had slipped away out the back door of the building. Upon realising this, my friend told me there was a dinner being held in his honour just a block away that he was hosting, and suggested I join them. ‘OK’, I said, noticing it had begun snowing, and wondering why on earth I’d decided, out of all nights, to wear my new suede shoes.

A still from Tajrobeh (The Experience, 1973)

There he was, standing right in front of me, sans hangers-on and acolytes. I thought it would be strange if I didn’t say anything to him, yet, at the same time, found myself at a loss for words. If my friend hadn’t introduced me to him, I probably would have remained silent all night. I can’t recall exactly what he said, but my companion mentioned my magazine and the sorts of things I was involved with. I anticipated that my encounter would end that very moment; to my surprise, however, Kiarostami struck up a conversation and flashed his pearly whites. I handed him a copy of the magazine in one of REORIENT’s ‘Sex, Drugs, and Gol-o-Bolbol’ tote bags, and before we headed to the table, simply told him that I had long loved his films and was very happy to meet him. Yeah, he’s alright, I thought, walking upstairs, feeling fuzzy in the afterglow.

At one end of the table, I espied Atom Egoyan. Sitting directly across from me was Kiarostami, with whom I merely exchanged glances and smiled every now and then. Myriad conversations were happening, and, for whatever reason, I and the people around me began talking about Freddie Mercury. The bizarreness of it all soon began to sink in, and, at one point, I turned to another friend beside me and asked, ‘Is this for real?’ It has been said that in Kiarostami’s films, the ordinary and mundane become extraordinary. That evening, it was exactly the opposite; there I was, sitting across from a man deemed one of the greatest-ever directors in the history of cinema, talking about rock and roll as if he weren’t even there: the extraordinary had become unsettlingly ordinary. Perhaps it was because of the way the man carried himself; he largely kept to himself, and, though the sole reason of the gathering, wasn’t asking for any attention whatsoever. With such an oeuvre as his, anyone else would have been content with simply enjoying their spiced chicken, too.

A still from Zang-e Tafrih (Breaktime, 1972)

Minutes turned into hours. I hadn’t yet met Atom Egoyan, but, being incredibly gracious, he came around to say goodbye as I was busy downing a mouthful of saffron-scented rice. I also said farewell to the person who had earlier on interviewed Kiarostami in the theatre, and who was noticeably peeved by the fact that I didn’t know he was the Director of the Film Festival. Oh well. Outside, I shook hands again with the man behind the shades beneath falling snowflakes, hoping I’d see him again. The restaurant had closed for the evening, and a taxi was waiting to take El Padre back to his hotel. Just as I was about to leave, he began feeling around in his pockets with a look of agitation. ‘My magazine! I forgot my magazine …’ Thankfully it was still where he had left it in the restaurant, which opened its doors again for us. ‘Uh, befarmaid’, I said, blushing as I handed him the tote with the magazine in it. ‘Khoda negahdar’ were the last words I said to him before he hopped into the orange cab and I began brushing away the little white crystals that had settled in the thicket atop my head.

* * *

‘Once you’re dead, you’re made for life’, Hendrix once said. If there’s anything that brings consolation to me now, it’s that Kiarostami was one of those rare artists who were celebrated as luminaries for a great deal of their own lifetimes. ‘Ah, Iran! You guys make great movies’, my friends would often say to me. They most probably hadn’t heard of Gheysar, and certainly not any of my beloved Nasser Malek-Motiee flicks. Hell, they probably didn’t even know where Iran was on a map; but a mere mention of Where is the Friend’s Home? would usually get a few nods, at the very least. Being heaped with praise by industry giants, film festivals, and connoisseurs is one thing, but being a household name in the unlikeliest of places is another. Iranian cinema flourished outside the career of Kiarostami, at home and abroad, as it will continue to; but to merely say that Kiarostami helped make Iranian cinema the darling it is today is a wild understatement.

‘At dawn, don’t you want to see the sun rise? The red and yellow of the sun at sunset, don’t you want to see that anymore? Have you seen the moon? Don’t you want to see the stars?’ (A still from Ta’m-e Gilas (A Taste of Cherry, 1997))

On the way back home, high up in the skies, I thought about how I would remember Kiarostami as I battled a fever. None of the many titles or laurels he garnered will come to mind, nor will any of the accolades given him by his contemporaries. The name ‘Abbas Kiarostami’ won’t get me thinking about the greatest this or that, or the pioneer of such-and-such. Rather, I will recall the simple and kind man who opened windows into my country and culture in ways no one else could. A man who deepened my love for my people, and gave me a new understanding of what it meant to be Iranian. A man who, with his childlike heart and soul, reminded me of the overwhelming beauty of life, which can always be ours and is always waiting to be beheld by our eyes – if only we open them.

With special thanks to Henry Kim.