Musings on the legacy of the age-old Iranian art of escapism

I slip through cracks, I burn holes. I slide between fingers, rip asunder the night. I speak in hidden tongues, nestled between dusty pages daubed in the ink of the unseen. I am guided by the undulating spirals of knowing eyes and the soft depressions of my mind. I tug at the fringes of shadows, ever in pursuit of the memory of light. At times this light seems so palpable, while at others, I have to squint hard enough to remember its warm orange glow amidst that black nothingness. Smothered in cinders and ash, I am known by many different names: they call me Khalil Oghab, Daedalus, the one that got away. Others, like me, have been burned, and some, beaten. Illegitimi non carborundum, I say. There is always a way out, always an aperture to squeeze through. I am an escape artist.

* * *

Under this roof, I will tell you about flowers, the stars, the night sky …

Somewhere, in a remote corner of the Persian Gulf island of Qeshm in southern Iran, have a covey of people made their homes. Certain objects strike one as familiar: refrigerators, carpets, valises, jugs of water. Perhaps, aside from the people themselves, they are the only things one can establish any sort of relation with. What are these towering masses of sand and stone? The ancient bed of a sea that once was, most probably; but they look too perfect, too human, to have been the result of chance and geology. They remind me of the crumbling ruins of Nain and Abarqu, two other dots out in the boondocks forgotten by God and man alike, synonymous in Iran with ‘the middle of nowhere’. Where the fuck is Qeshm? Does it matter? What is significant is that these people have been driven here with only the shirts on their backs – and in some cases, not even that. A camel lies dead on the parched earth, its hooves fettered; elsewhere, a man lies huddled up in the foetal position upon a roughened mound. Shrouds of black have been tossed upon the sand, and the Pieta is echoed in the hollows of a grotto: the death, presumably, of the past? The dromedary’s corpse reeks of foreboding; death and decay here do not herald a rebirth of any sort, but only the beginning of the end. Their only roof, the sky, their only bed, the hard earth, ablaze beneath the sun and frigid in the moonlight. On the other side of the world, in some stuffy club in Greenwich Village, a corkscrew-haired beatnik who tips his corduroy cap to Old Bob is whining words through his nose; but he doesn’t know ‘how it feels’, does he? He doesn’t know anything about these woebegone wights in godforsaken Qeshm, or those little Syrians sleeping with the fishes.

From Gohar Dashti’s Stateless series

No one can tell for sure what has brought these people here, and why they’ve had to flee their homes; and, as with the whereabouts of Qeshm itself, it doesn’t matter. Famine, war, natural disasters, whatever – we only know that the journey won’t be the last they’ll make. Whether they’ll have to drag their feet to some other wretched place again, or rove within the folds of their minds and create, somehow, a mock imitation of their past lives, they’ll never know a moment’s peace. Once uprooted, forever uprooted. New soil will invite them to wither away, God knows where, while the old soil – transformed, evolved, changed – will never be the same. Only its vestiges shall remain, if not devoured by time. The camel shall not rise again, let alone pass through the eye of a needle.

From Gohar Dashti’s Stateless series

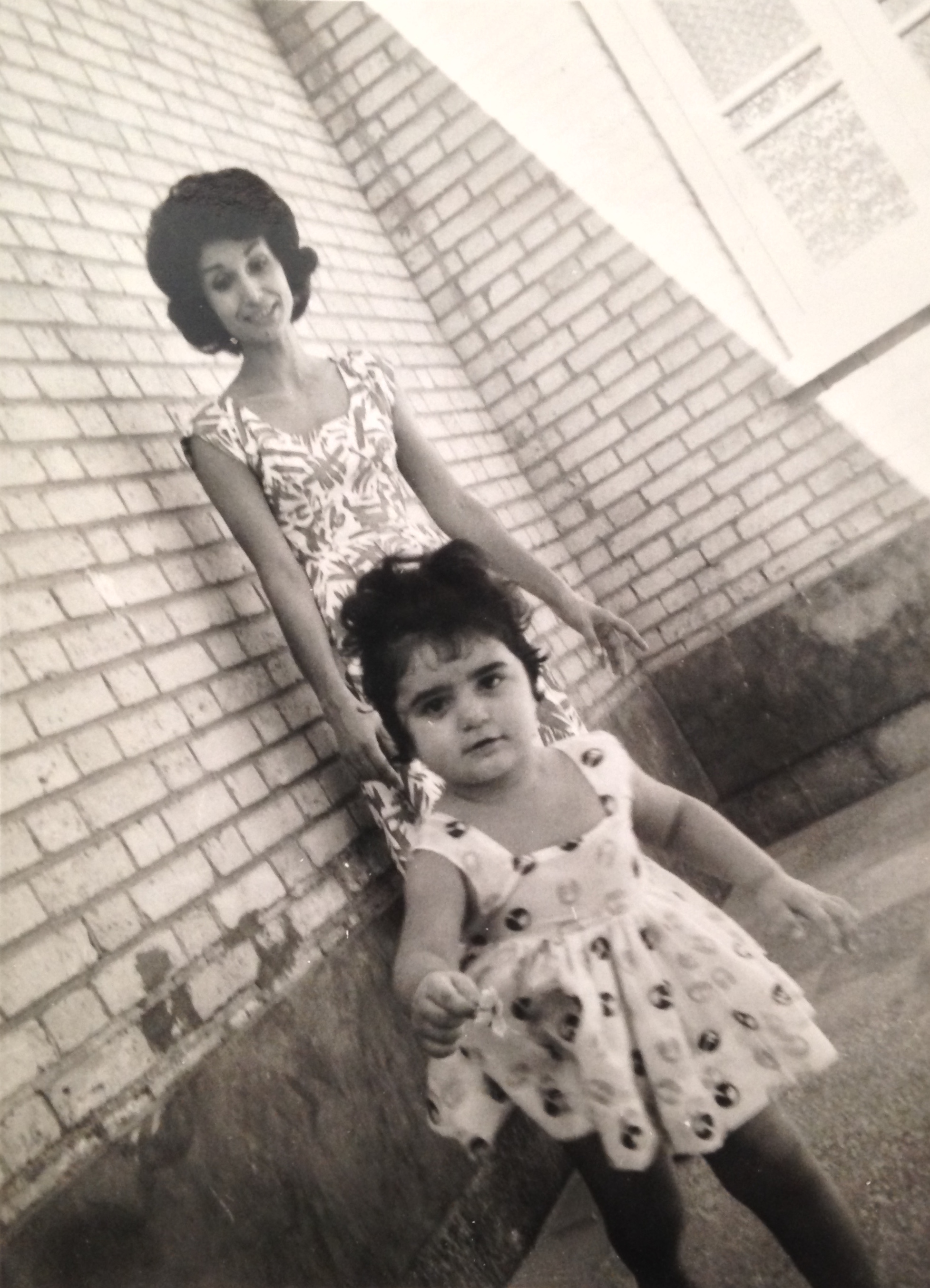

I don’t know much about Ahvaz, other than that my maternal grandparents lived there for a while, as did my paternal ones, owing to their connections to the army and the Iranian Oil Company. My father never cared much for it, having always preferred nearby Abadan. Come to think of it, nobody in my family had a particular affinity for Ahvaz; they just, owing to circumstance, happened to find themselves there, and had to make the best of things. I suppose it wasn’t all that bad. Sure, there were the occasional sandstorms, swarms of locusts, and the stifling heat that would melt the pavement beneath one’s shoes; but there were also ice cream sandwiches, noon khameii, and rivers of black gold.

Whatever happened to Ahvaz and Abadan, those cities in the land of the Khuz? Yes, there was 1980 ‘and all that’, and both are still standing proud beneath the Iranian and Brazilian flags alike; what I mean to say is, what happened to the Ahvaz and Abadan of my parents’ childhood? Tucked away beneath my bed are shoeboxes full of photographs of old ghosts and relatives. I’ve never been to southern Iran, but I can tell the thick Polaroids taken in Ahvaz apart from the others; those cream-coloured brick houses and empty expanses are dead giveaways. For my relatives and I, though, they’re little more than miniature visual aids that shine every which way. Our memories are fuzzy to begin with, and, as such, they don’t exactly help elucidate things any further. Has our Ahvaz, the only one I’ve ever known, been lost forever? What if there weren’t photographs to smear and play with in the light?

My mother and grandmother in Ahvaz, Iran, in the early 60s

In Berlin, there is a bottle. Its shape is peculiar, and resembles something between a clothes hanger and a pomegranate. It looks like it belongs in some sort of sanatorium rather than someone’s flat, and as if its contents are waiting to be consumed, perhaps through injection or inhalation. There aren’t any holes or perforations; nothing can enter or exit the apparatus. Contained within it is not any balmy Teutonic air, but the air of Iran, of Ahvaz, deemed to be amongst the most polluted in the world; and, suspended in that air is not only the ancient dust of Khuzestan and exhaust, but also a million images, smells, and sounds of yesteryear and millennia past. It is the common thread linking mighty Elam, the armies of Darius the Great, d’Arcy, and Mum’s cherished ice cream sandwiches. As long as the delicate glass object isn’t smashed to bits, the prized air d’Ahvaz will remain pure and unsullied for centuries to come. Its proud owner can rest her head on her pillow and take refuge from the frosted streets of Berlin in the glowing warmth afforded by the bubbled breath of her homeland.

I have grown up surrounded by bubbles, bottles, and other such receptacles. I have even lived in them myself, for they are some of the many heirlooms that have been bequeathed unto the Iranian people.

Anahita Razmi - Air d’Ahvaz (courtesy the artist and Carbon 12)

Something told Grandpa he had to leave. Epithets like ‘Cat Killer’ and ‘Hanging Judge’ just didn’t sit well with him. He didn’t like all that talk of ‘us’ and ‘them’, about blasphemy and righteousness and the stains of depravity and decadence that had to be wiped off the soiled face of Iran for good. It was all too familiar; he’d heard it all before, and didn’t want to sit around to see how things would unfold. He remembered the stories his father had told him about the Russian Revolution, and how, as a child, they’d made his hairs stand on end. Poor Sheykh Kazem! How could he have guessed on that cool April’s eve in Badkubeh that he’d walk out onto the cobblestone streets below to find them awash, in the morning light, in every hue of red? How happy they’d all been after hearing of the fall of the Tsar; the Russians, everyone thought, would pack their bags and quit sticking their noses in everyone’s affairs, once and for all. Little did they know that they’d come marching back again in those shiny black boots with renewed vigour, ready to sink their teeth into Iran once again and tear it into pieces. White? Red? Same old, same old. The bastards didn’t have mercy on their own mothers; how could anyone expect to remain unscathed, especially Sheykh Kazem – the ‘Master of Merchants’ – with all his choice wares? Damn the heavens! What enmity did God have with that beleaguered trader? First, my cartons of glass, smashed to pieces on the shore, he thought, then, my loads of tobacco, scattered in the snow – and now, this! Ah, if only the great Mirza Kuchak Khan had been there to lay down the law of the jungle; but no, Khaloo Mirza was busy kicking ass in the besieged forests of Gilan. Alone and destitute again, amongst the infidels – O, poor Sheykh Kazem! God bless your soul!

Sheykh Kazem Tehranchian

If it hadn’t been set in stone, Grandpa made sure to hack it in himself. They would leave Tehran for London at the first opportunity. Why would they leave Tehran? Because ‘they’ were coming to get ‘them’ – of that Grandpa was sure. He didn’t make any distinction between vermillion coattails and greasy, swarthy beards. They’d snatch everything they had from them, he thought; yes, they’d eat the rich alive! And why, out of all the places on earth, would they make for pitter-pattering London? Because his brother, Amoo Mohandes, a.k.a. Agha Dadash, was living there in Hampstead. Tehran for the Tehranchians was no-man’s land. As with my father’s side of the family, Grandpa was too conspicuously tied to the old ‘idolatrous’ regime, and if the pasdars didn’t come looking for him sooner or later – or so he thought – it would only be a matter of time before a neighbour or old ‘friend’-turned-revolutionary would tip them off. Perhaps it wasn’t as much of a conspiracy as he’d thought, though; someone, for the sheer hell of it, reported my family to the authorities. To Grandpa’s fortune, and the displeasure of the nefarious individual, the venerated name of Sheykh Kazem – may God have mercy on his soul! – saved the day.

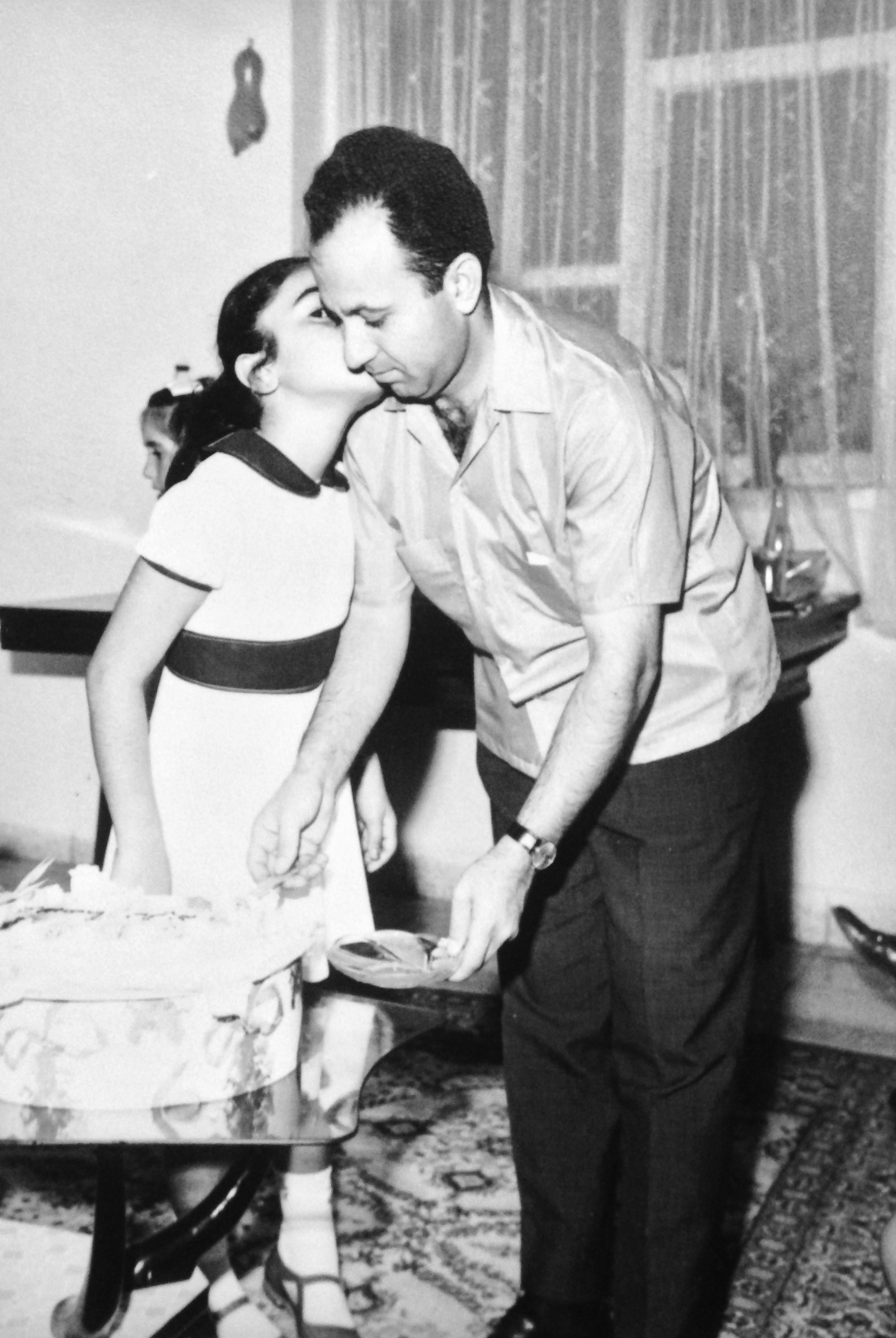

Mum and grandpa in Tehran in the 60s

Just as Sheykh Kazem couldn’t have imagined that he’d wake up to see Badkubeh infested with Bolsheviks, neither could Grandpa see then how his life would forever change. The move to London wasn’t just physical; it wasn’t only a land he had left behind, but also a life. In Tehran, the names of him and my grandmother had carried weight; they had meant something. In London, they became Mr. and Mrs. T., the quaint Iranian couple with the Persian rug doormat, from whose windows often came the smell of sabzi polo. They didn’t have anything against the English, but just couldn’t dig George Michael and Black Adder (Freddie Mercury was a different story), or wrap their tongues around their language (why even bother when they spoke that of poets?). There wasn’t really anything quintessentially ‘English’ about them altogether, come to think of it; like those trees in the desert, they’d been uprooted, and had to try, somehow, to make do with their new surroundings. My grandparents’ way of doing this, I suppose, was to recreate their apartment on Tehran’s Vozara Street. You won’t see it marked on any maps, but in a little flat, just a stone’s throw away from Marx’s grave (poor Sheykh Kazem!), can be found in north London, proper and prudish, a little Iran. There, the only voices heard are those of Hayedeh and Shajarian; within, one sits on Persian rugs, flowery and faded, burning their tongues on hot cardamom-infused chai that’s been brewing for an entire morning, beneath the languid gazes and arched eyebrows of bare-chested Qajars. On the living room table can always be found pistachios – which, although nowhere near as tasty as those from Rafsanjan, satisfy the palette yet – powdery sweetmeats, and a decaying volume of the odes of Hafez. While it may be difficult to decipher the gilded curves in the frame hanging above the sofa, all you need to do is ask, and Grandpa, assuming the air of the Bard of Shiraz himself, will reveal its meaning: Wash thy prayer rug with wine, should the old Magus deem it fine. Telephone calls are answered with a ‘So-and-so jan, can you hear me? Alo?’, and doorbells with a ‘Befarmaid‘. More often than not, it’s Auntie who’s come for lunch, or my cousin Shahrzad, to give Grandma the uncensored lowdown on Iranian high society in London, brimming with all the juicy, sordid details.

… But when all is said and done, we know that we will always slip through those cracks and slide between those fingers; we, Iranians, of the burnt generation and golden years, of the centuries of darkness and silence, of the wine-drenched tongues of bards

They live in London, but they don’t. They live in Tehran, but they don’t. Where do Grandma and Grandpa really live? When they left their apartment on Vozara Street, Grandpa wasn’t thinking about stuffing any air into bottles, or pickling any mementos; he didn’t need to. In London, their little flat would become a bottle itself, a living, breathing memento, a capsule of the life they’d left behind and in which they would relive their memories: a work of escape artists par excellence.

Mona Hakimi-Schüler - Dreaming the Past (© Michael Klaus; courtesy the artist)

My grandparents didn’t want to become escape artists; they had to. As did I. What else could I do, down on my knees in suburbia? A volume of poetry strikes a chord; before you know it, you’re digging through your old schoolbooks again, tracing the confounding dotted letters with your fingers like a blind man, cursing the very idea of abjads and taking a stab at what vowels might lurk between those thick black swirls. After reading stories of Daddy-o and his bread, you start developing a thing for Behrouz Vossoughi and the fuzzy-wuzzy black-and-white sixties flicks that never fail to jam right before the belle in the miniskirt takes to the stage. You hang around chelo kababis, become addicted to tea, and ask your mum what the hell Shajarian is chah-chah-ing about. Your parents tell you you’d be better off reading about how to make money and hit the big time instead of the Tuti Nameh, the Chahar Maghaleh, and other books ‘no one reads’, but it all goes in one ear and out the other. You do it because your heart and mind are somewhere else, because the world outside has always been so cold and strange, and because there’s no place you’d rather be than the hearth of your mind, of your soul, where moustachioed lutis fall in love with prostitutes, bards sing of lovers to the twang of the dotar, and daevas are damned. You do it because as an Iranian, it is an instinct, an impulse surging at once through body and mind. It is the legacy of poets, lovers, and punks alike.

‘Where moustachioed lutis fall in love with prostitutes …’ (Bahman Mofid in the 1969 film Gheysar)

Daqiqi did not love the world he lived in; or, rather, the world did not love Daqiqi. The House of Sassan had crumbled, but its memory lingered yet. The land of the noble had been smothered in billowing black shrouds, but shining beneath could still be seen gilded swathes of deepest purple and red. The vicissitudes of cruel time and fortune had humbled Daqiqi into submitting to the new world order, but had failed to extinguish the flames of love for what he most held dear: the ruby-coloured lip, the harp’s lament, the blood-red wine, and Zoroaster’s creed. If only, like Damghani, he’d yearned for kebab, wine, and the robab! Perhaps then would he have been able to bring his masterpiece to completion. O Ferdowsi, poet of Paradise, the world reveres thy hallowed name. But what of you, Daqiqi? You longed for the ruby-coloured lip, but were murdered by a Turkish slave. Like Hallaj before you, you paid for your tongue with your head.

The ruby-coloured lip, the harp’s lament, the blood-red wine, and Zoroaster’s creed … (A Safavid-era fresco from the Chehel Sotoun (Forty Columns) palace in Esfahan, Iran; courtesy Eric Lafforgue)

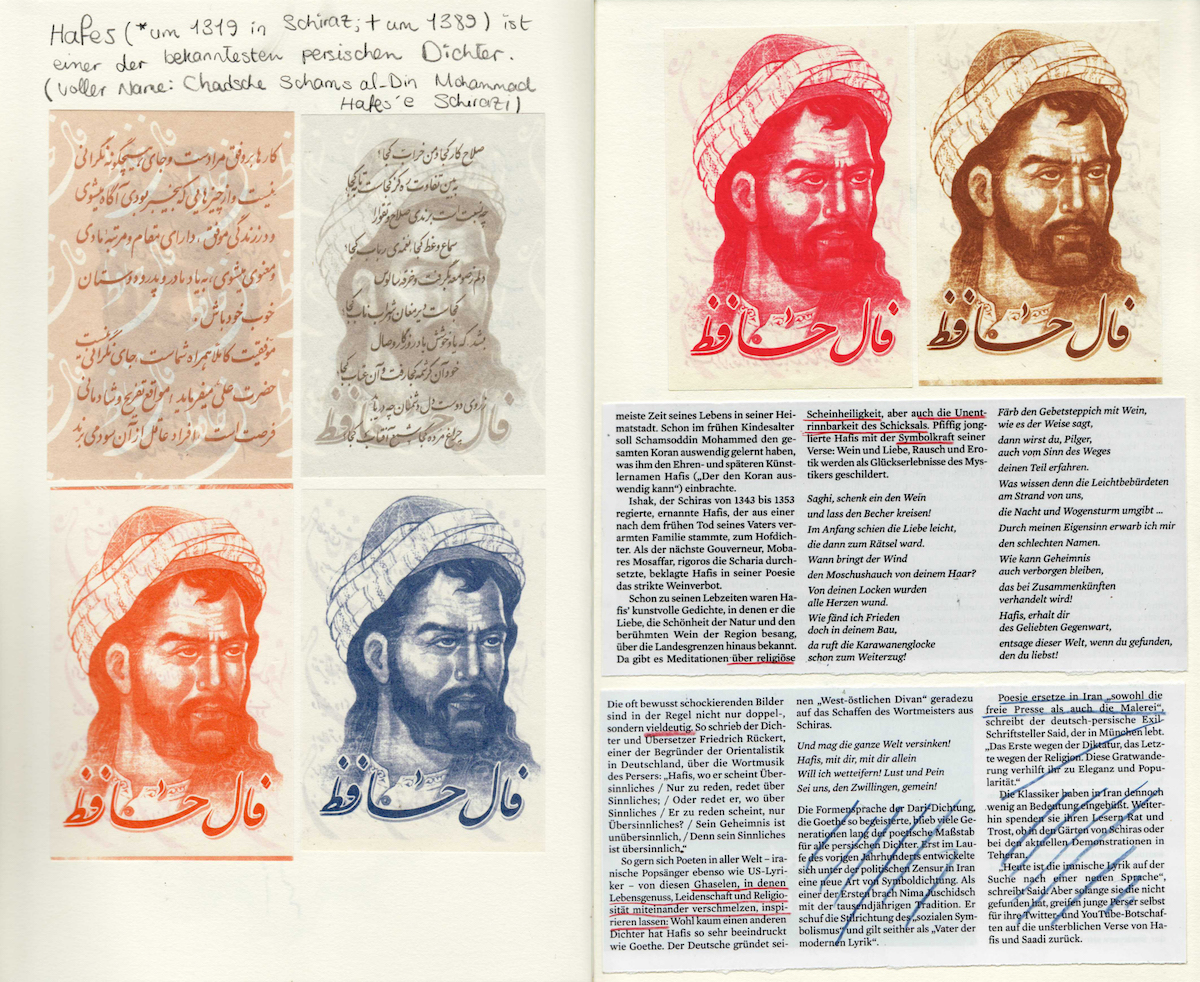

Other children of the night, born of darkness and silence, fared better than Daqiqi. They spoke in allegory and metaphor, in riddles and rhyme. Veiled beneath flowers and musky ringlets lay the hidden meanings of their words, sometimes stupefying, always sublime. The ‘beloved’ could have been a damsel, or, more likely, a page, depending on how one saw things; and, perhaps bulbuls and hoopoes really were just bulbuls and hoopoes. Unorthodoxy and free-thinking were seldom presented as such, often being clothed in the austere raiment of faith. Man and God, one and the same? No, no – he was speaking of an earthly beloved – bite thy tongue! In any case, those who went against the grain did so in the footsteps of Daqiqi. Khayyam and Razi (how well the two would have gotten along) managed to evade their detractors unscathed, as did the drunken Bard of Shiraz, although all were labelled heretics. The pages of Hafez’s Divan are soaked in wine, the wine of the Magians, of the tavern, of ruins. Was it all mere allegory and a matter of aesthetics? May I be struck dumb! Hafez didn’t long for the temple’s flame and the ways of the wine-imbibing Persians of old. No! Wine, the Magian Elder, the tavern – they were only metaphors! Hafez – God forbid – couldn’t have been a closet-Zoroastrian and a toper – or could he? Hafez, you sly genius, you. For eternity hath the Magi’s ring been on mine ear; we are those who were, and them shall we forever be. Legend has it that upon his death, Hafez’s critics were reluctant to give him a proper burial on account of his ‘heresy’. To put an end to their quandary, they opened a page of his dripping Divan at random, and were met with the following lines: Turn not away from the bier of Hafez; steeped in sin, he shall enter Paradise!

Needless to say, Khajeh Hafez of Shiraz was soon interred within the life-bestowing earth of Shiraz. He had his cake, and ate it, too.

Mona Hakimi-Schüler - Poor Hafiz (courtesy the artist)

Some punk at an underground Tehran rave probably has it in his head that he’s a badass hoisting high the flag of the ‘burnt generation’. Intoxicated by music, coke, and the lascivious glances of the pretty girl in the corner licking her lips, his high is intensified at the thought that he’s managed to get away with it all, right under everyone’s noses. He is there, in his subterranean sanctuary, feasting his senses in a way that would make even those in ‘Dobai Dobai’ and ‘Tehrangeles’ salivate with envy. Tehran isn’t such a bad place, after all, he’s thinking to himself, wiping his nose and feeling a hot bulge in his trousers. What he doesn’t know is that this isn’t his legacy, or even that of the romanticised burnt generation that thinks it’s seen it all; he’s merely the heir of the countless Iranians before him, who, through their genius and artistry, managed to fashion worlds for themselves removed from those they knew. And, what that ‘badass’ also fails to realise is that in place of the whip and the electric shaver, his forefathers once trod beneath the shadows of gibbets and blades.

From Melika Shafahi’s Tehran series

Tell me – without you, what stream shall quench the desire of parched lips?

Without you, in what breeze shall I seek a refuge from my weariness?

Googoosh is on the television again; but 1970-something is long gone. It must be a clip from a videotape, perhaps pulled from the magic bag that is the Iranian supermarket, or something stumbled upon by chance on an LA station. Googoosh is singing about a separation gnawing at her, eating away at her being; without her beloved (God? Saeed Kangarani? Some hypothetical figure sprung from the pages of Persian romance?), she simply cannot find the strength to carry on. The title of the song, Hejrat, recalls the flight of the Prophet Muhammad and his followers from Mecca to Yathrib (later ‘Medina’) in 622 A.D.; other migrations, however, are implied by the scene in question: the flight of the Shah from Iran in 1979, the flight of the family itself, the flight and disappearance of a life once led. The members of the family have gathered around the television in silence; not a word is said, or needs to be, as they can all intuit each other’s thoughts. Everyone is thinking the same thing; Khanum Googoosh’s words are only adding to their pertinence and poignancy. Heads are slightly titled to the side, and displeasure and nostalgia meet in their expressions. A sarcastic huff is imminent, as is the dreaded lump in the throat. How can they go on living without Googoosh, especially when she herself is speaking of her own despondency? Should they, like Googoosh, ‘weep as long as they live’, and see ‘happiness die before them’? Neither did Googoosh do that, nor have they done so. Like my grandparents, they have created a little Iran of their own, replete with Persian rugs, démodé rococo sofas, Googoosh, and all. They have yet again worked their wonders as escape artists, in the spirit of their forebears. There may be a glass receptacle in Berlin filled with the blessed air of Ahvaz; but it is merely one of many. Tehrangeles, Tehranto, ‘behind closed doors’ in Tehran, my grandparents’ flat – what is the Ahvazi specimen in comparison to these animate bubbles and ampoules?

The cover artwork for Sholi’s Hejrat (photo by Michael Aghajanian; courtesy Payam Bavafa)

Once, a few years ago, a friend of mine invited me to his place in Rudehen, a small town on the outskirts of Tehran. I didn’t know what to think. As with Qeshm, the only thought that popped into my mind had to do with Rudehen’s obscure whereabouts and an expletive; I could have been on my way to Abarqu, for all I knew. So be it, I thought. If I was going to enjoy a day away from the hysteria of Tehran, it might as well have been in the sticks.

Rudehen was – as I, a typical Tehrani, had imagined – underwhelming. My friend’s pad, on the other hand, came as a welcome surprise. When describing Rudehen, my friend had spoken of stars in the night sky and nature’s bounty; a little oasis wasn’t exactly what I’d been expecting. We had Indian food, listened to electric blues, discussed the oil paintings on the wall, and reclined on cushions adorned with the face of Forough Farrokhzad. I could have been at a friend’s in London, if only I’d forgotten about Rudehen and the little mosque down the street. I actually began to like the idea of living by myself in a sort of secluded capsule, far from the pandemonium of the big city, doing whatever I wished in private. My own private Rudehen, I thought to myself, laughing at my own words and wondering what on earth had happened to Keanu Reeves. Just as I’d fashioned my romantic little world of Persian poetry, folk epics, and Film Farsi heroes as a way of bearing the boredom of the ‘burbs and my uprooted state, so too had my friend created a getaway for himself as a means of dealing with a world he didn’t find as welcoming as he’d liked. Staring at a cushion, Forough’s pretty face melded with that of an artist friend back in Tehran; her words took on a new significance, and rang as clearly as ever in my ears. I could picture her in her studio, fanning her sweating self in the midsummer’s heat and flicking away the ashes of a burning cigarette: ‘Don’t think we’re the majority here, Joobin jan. We’re living in a bubble we’ve created for ourselves.’

From Mahsa Alikhani’s Kate Moss Family series (courtesy the artist and artclvb)

The verses of Daqiqi and Hafez. My grandparents’ flat, and my friend’s in Rudehen. The air of Ahvaz, bottled up for centuries to come. The ‘hearth’ of my mind. They all belong to different times and places, but have all been necessitated by one and the same thing: the longing for something more, something better, as a flaxen-haired Faithfull once sang. Whether we have moulded our bubbles owing to physical displacement, in response to the unforgiving Fates, or as a result of the fear of dogma and orthodoxy, we have done so instinctively, evoking the spirits of our ancestors and in true Iranian fashion. The bastards – whoever and whatever they may be – will forever try to grind us down; but when all is said and done, we know that we will always slip through those cracks and slide between those fingers: we, Iranians, of the burnt generation and golden years, of centuries of darkness and silence, of the wine-drenched land of the noble.

Cover image from Mahsa Alikhani’s Kate Moss Family series (detail; courtesy the artist and artclvb).