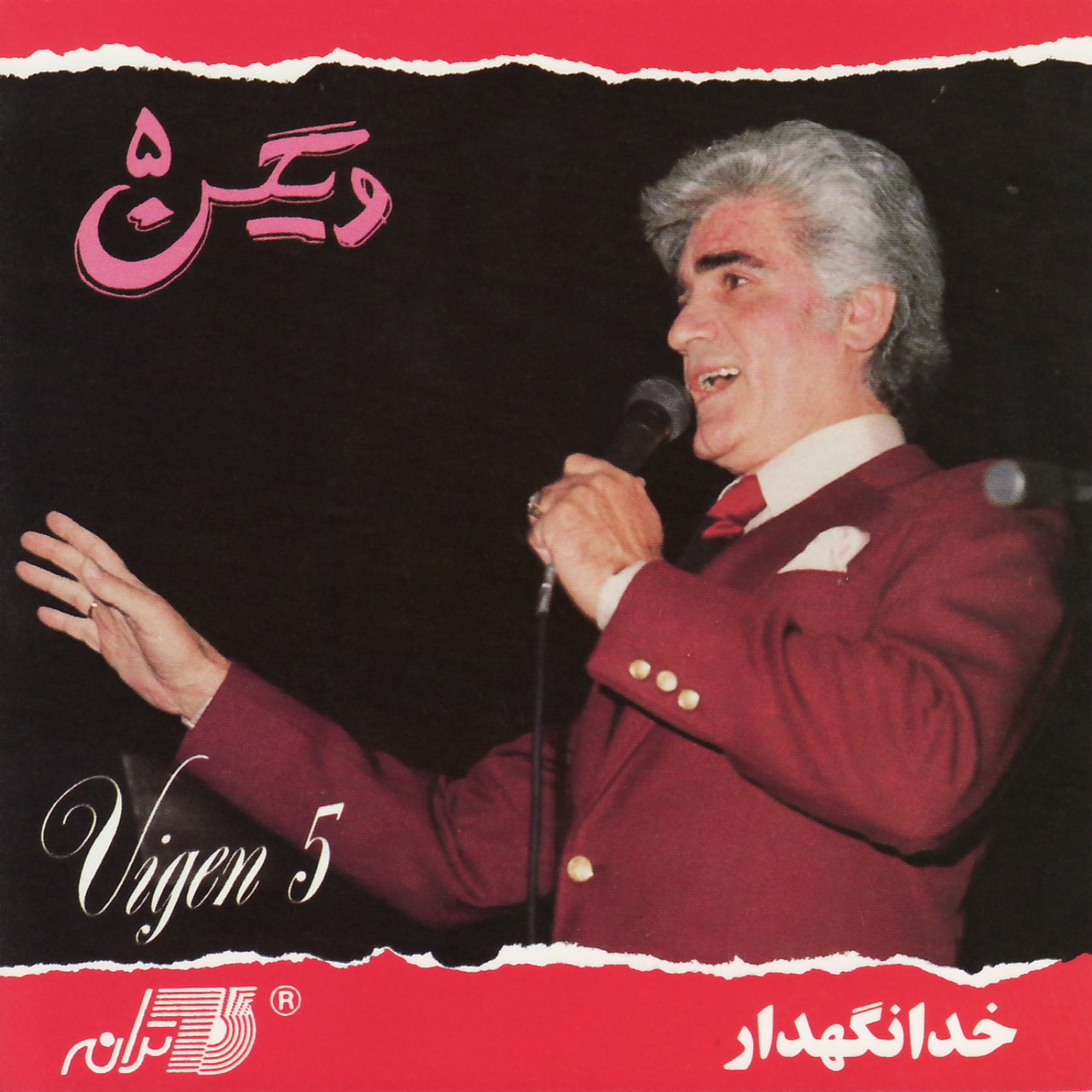

Armenian and Persian tales on vinyl, as dangerously funky as ever. Just don’t call them ‘exotic’.

Lara Sarkissian is a lucky girl – and she knows it. A filmmaker, creative producer, curator, and DJ of Iranian-Armenian descent born and bred in San Francisco, Sarkissian is the proud owner of boxfuls of vintage Persian and Armenian records, all thanks to the efforts of her mother and uncle, who packed them in their suitcases when they left Iran and Armenia for the States. Known to her fans as ‘Foozool’ – Persian for ‘nosy’ – Sarkissian has been making a noise in the West Coast with her experimental mixes often combining electronic sounds with traditional ones from Armenia, Iran, and the greater Middle East. For REORIENT, Ms. Foozool has put together a smashing selection of retro Persian and Armenian tracks, which more than compensates for the envy she’s inspired in me.

How did you stumble upon your mother’s record collection? Were these records that were being played at home, or did you have to do a bit of ‘digging’?

I came across a stack of my mom’s Armenian and Persian records in some storage at my family’s home in San Francisco. None of them had been played since my family moved here from Iran around 40 years ago, so it was definitely an emotional experience playing it all for my mom and nana after so long. These records hold a lot of memories – as a lot of sentimental objects that immigrated with them do – and the last ones of them were from the Armenian community in Iran they lived in. So, in a way, it was special recreating something with the records here. My mom had mentioned that these were very close to not being packaged and making it out here; but she finally decided to make it work and pack them all under her suitcases. ‘I never imagined while collecting these that I would have a daughter who would listen to and play these for me, and that it wouldn’t be in Iran’, she said.

My mom would constantly pop into my room and tell me stories she was reminded of while playing them; I chose to make the mix in her presence and have her involved for this reason. It can be difficult getting narratives out of a family when there is no specific subject or object being the cause of discussion – so I’m glad these records became just that. There really isn’t any other way to describe the feeling that wouldn’t sound too cliché, but it felt as I had connected with a younger version of my mother the moment the needle dropped on the records and played the distorted tunes. It felt like the sound carried memories and was burdened, in a way. I think the physicality of it, combined with the aural and sensory experience, made it feel that way.

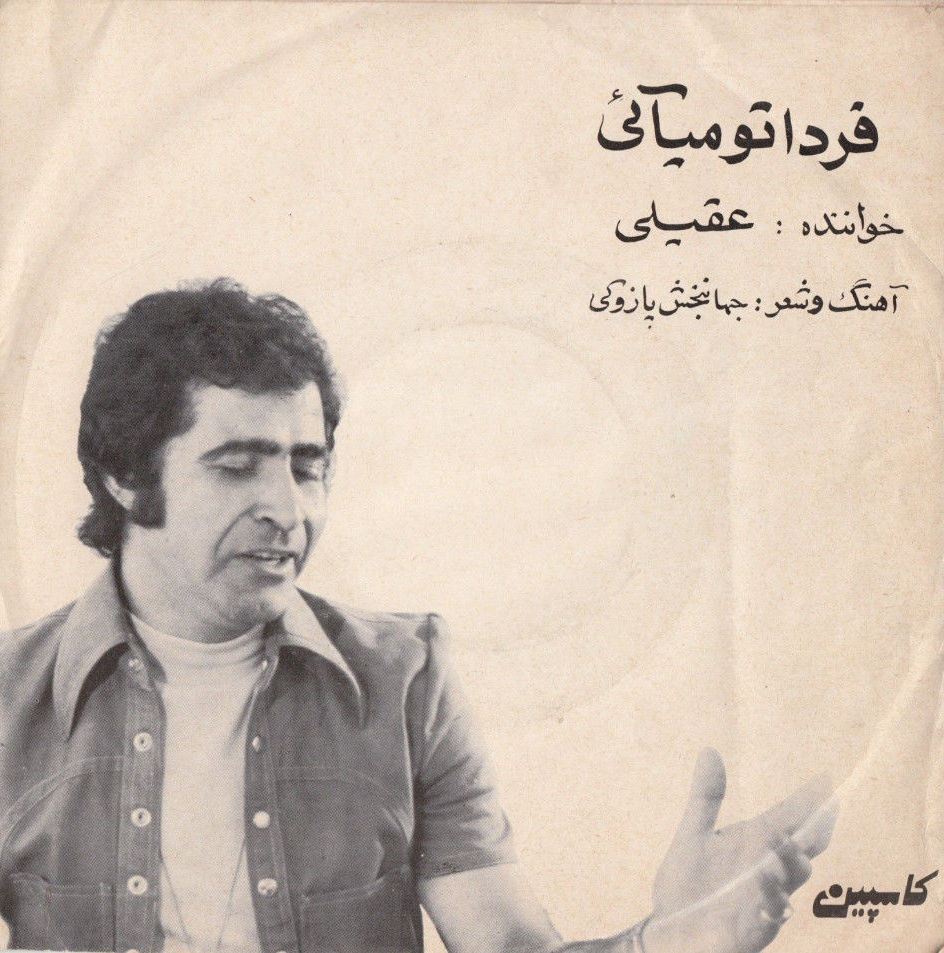

Tomorrow, tomorrow … (Hooshmand Aghili’s Farda To Miai (You’ll Come Tomorrow) on the Caspian label)

Half of these were bought in Iran, and the other half was brought by my uncle Gurgen to my mom from Armenia. Sadly, a lot of the Armenian records had artist and track information written in Russian, since they’d been released while Armenia was still a part of the Soviet Union – even records of folk and traditional music (e.g. by Komitas and the Sayat Nova ensemble); this is cultural information that I think should have been preserved and written in Armenian, especially when it comes to Komitas, since half of his original compositions and transcribed Armenian folk music were destroyed by the Turks during the Armenian Genocide and targeted for erasure. It’s definitely frustrating to see a more recent coloniser’s mark on them, contributing to erasure through language.

Were you always into Persian and Armenian music (both classic and contemporary), or is this a new thing for you?

I’m Armenian-American, born and raised in San Francisco, and my family is from Iran. Many of my relatives immigrated to Iran from Armenia during the Genocide in 1915, and some had even left before then. The Armenian language, as well as music, dance, and traditions have been inseparable for me my entire life, even though I was born and raised in the US. It often feels like I’m navigating four different worlds in the diaspora and my family household alone; but somehow, Armenian music and the arts bring them together, along with the Persian music I grew up listening to.

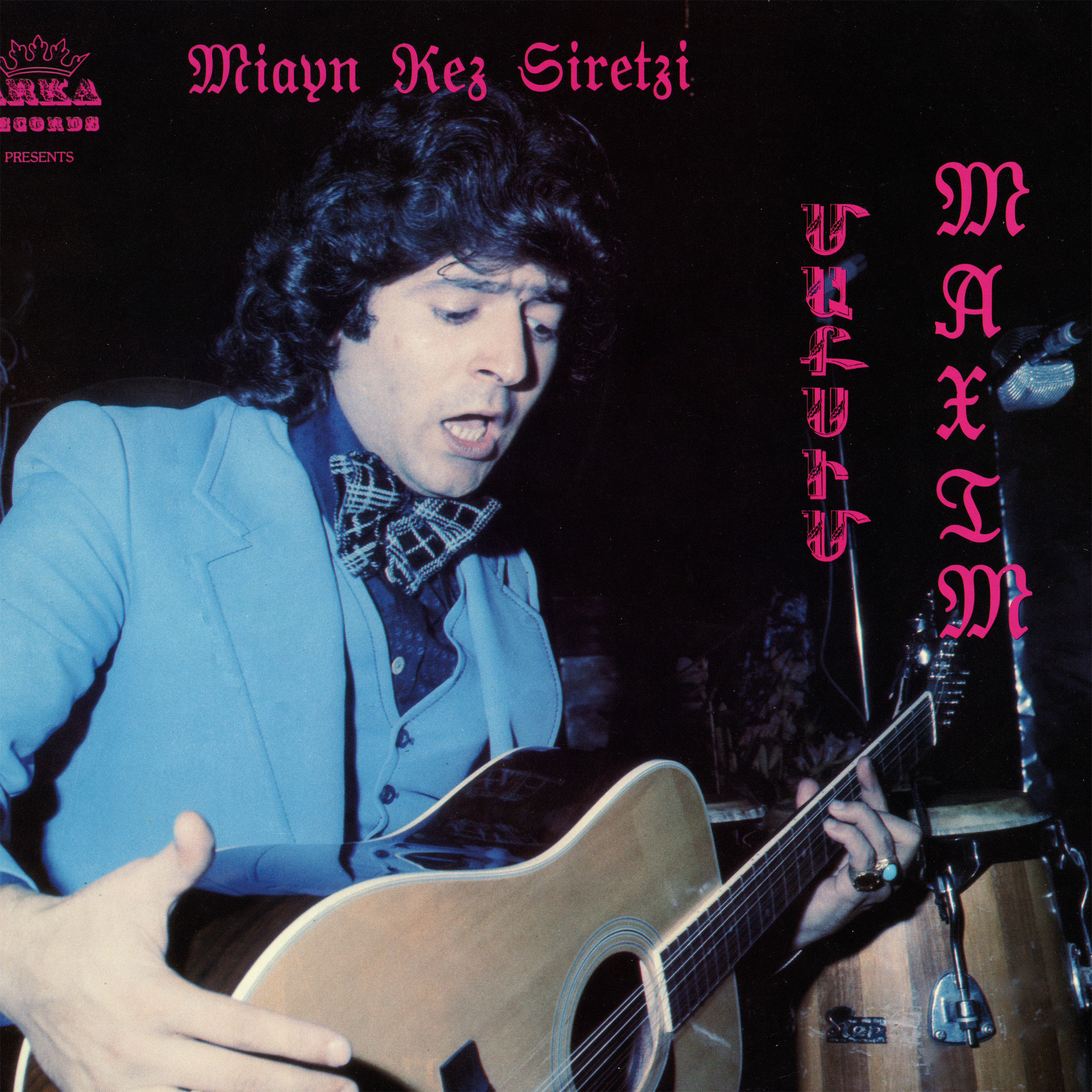

Hang on to that guitar, mate (the cover of Maxim Panossian’s Miyan Kez Siretzi (I Only Loved You) on the Arka label)

I attended Krouzian-Zekarian-Vasbouragan Armenian day school in San Francisco for 10 years. We studied and performed traditional Armenian music, literature, and poetry, and grew up singing and listening to sharakan (Armenian chants) and music in church. We were raised on family and community events that played traditional and contemporary Armenian music we’d shoorch par to. Persian, Assyrian, and Arabic music would also be played at weddings and family functions, depending on what country your Armenian parents were from. These sounds have always been around and a usual part of our lives. They’re always a place of comfort for me, and a way to make sense of existence and identities in the diaspora when working with and incorporating them in productions and mixes.

Now, I know I’ve written about the Western fascination with 60s & 70s Iranian records, but why do you think people in the States and Europe are digging this sort of music? When I was growing up, these Persian songs were considered demodé and/or cheap (with certain exceptions, e.g. Googoosh). It’s a bit surreal to see all these labels in the West devour all these obscure and funky tracks from places like Iran, Turkey, and the Arab world. I’m still waiting for the Armenian funk record to beat all other Armenian funk records, though!

I think we hear familiar Western sounds in Persian, Arabic, Armenian, and Turkish rock, funk, disco, and psychedelic records. However, we become fascinated by and obsessed with what’s different – elements (that have been around for ages) we often hear Westerners unfortunately call ‘obscure’: Eastern instruments, languages, melodies, rhythms, and vocals. We hear something that’s familiar, but not quite. This makes me think about the line between fascination and exoticisation. We hear terms such as ‘exotic’ and ‘otherworldly’ being used to describe sounds from the East. These ‘exotic’ and ‘otherworldly’ sounds have been around … for a while. They’re real, and have existed. There are many different peoples, languages, cultures, and religions within such densely populated and shared regions in the Middle East that have faced violence and been neighbours for centuries. I think Rachel Goshgarian explains it best in her piece on diversity in the medieval Near and Middle East, about how diversity is actually such a new concept in the West.

So, to simplify all this intellect, these different histories and real existences, and to use words like ‘obscure’, ‘otherworldly’, and ‘exotic’ to describe them owing to a difference in cultures is disrespectful. Fascination can be an appreciation, a celebration, a source of inspiration, and a way of digging into your own narratives and bringing awareness; but it can also lead some people to believe they feel ownership over something they have just ‘discovered’ that is ‘obscure’ and distant to them and the audiences they’re sharing it with, when what they have really found is something that has existed, something so personal and spiritual, and that can even be associated with past and present violence. It just depends on how one goes about it. This ownership includes work that people (particularly with more representation) choose to alter and edit – straying away from sources and the original voices and narratives of the material – for personal gain and credit. This goes beyond music and the arts, too.

‘I never imagined while collecting these that I would have a daughter who would listen to and play these for me, and that it wouldn’t be in Iran’, my mom said

It can be difficult and rare for many Armenian-Americans to find, feel comfortable participating in, and connect with Armenian spaces in America; it mostly depends on where you’re living in the country. Finding Armenian creatives alone can be difficult, and even on the Internet, you have to do a lot of digging. However, Armenian art and music themselves can sometimes feel like the most accessible things to cling onto for identity here – compared to a knowledge of and access to the language – when our history, language, art, and stories have undergone a pattern of erasure, displacement, and instability for decades, and considering that we are a scattered people. So, when a non-Armenian is fascinated to the point of altering Armenian music and stories, I am curious to know why. But of course, I get excited when someone learns about it, has an interest in it, and works with Armenians to preserve it.

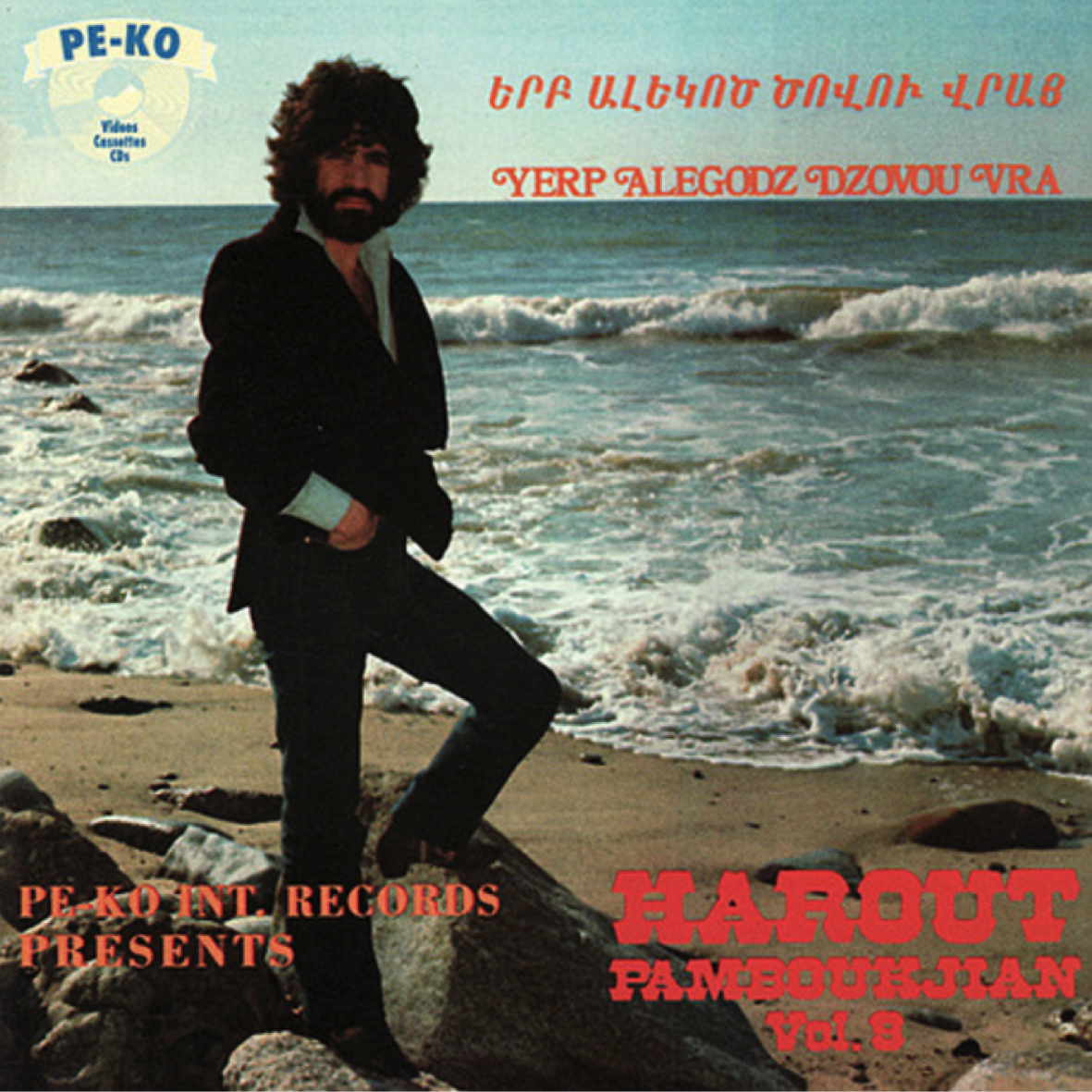

Son of the beach (Harout Pamboukjian’s Yerp Alegodz Dzovou Vra (Whilst on the Stormy Ocean) on the Pe-Ko label)

The question of whether or not those in the Armenian diaspora should turn traditional Armenian art and music into something ‘cool’, contemporary, or ‘relevant’ today is a whole other discussion in itself; yes, that should happen, and it is happening. We have our individual Armenian experiences in the context of the diaspora, and many stories and issues of identity and intergenerational dialogue that belong to them. However, as someone who was born and raised in the West, even within an Iranian-Armenian household and oftentimes feeling like I’m navigating areas other than strictly ‘Western’ or ‘American’, I still ask myself why I’m working with what I choose, and how my privileges play into that; it’s forever a learning process. But, how I identify as an Armenian, how I was raised, overlapping identities, and generations of lived and fought histories that are a part of me are issues that are still real and here.

How have American audiences reacted to your mixes, and this sort of music in general? I was at a swanky bar the other night in Toronto, and Googoosh’s Hamsafar came on. Mind-blowing.

All of my mixes end up being different from one another, so it depends. This one was a first: I only used Armenian and Iranian music specific to my mom’s collection. People have been generally excited about them, and it makes me so happy when listeners get stoked on something that’s close to me, or sounds I’ve grown up with. I’m also curious to know what people take from it, especially when it comes from my own sounds or samples I choose in production, since they can be pretty specific. I often see people lumping together all kinds of Eastern music as if it’s one big genre – which in the end, generalises entire histories and regions (that often experienced violent conflicts) for the sake of making the material easier to grasp.

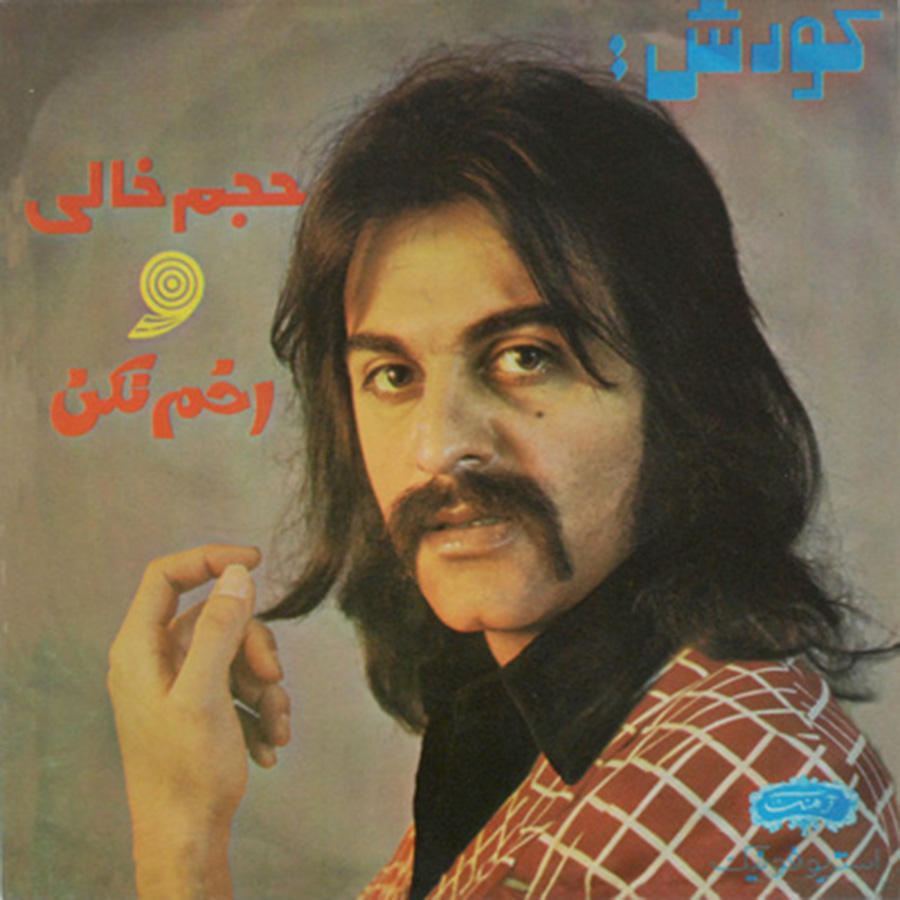

‘Tache goals (a Kourosh Yaghmaei single on the Ahang label featuring the songs Hajm-e Khali (Empty Mass) and Akhm Nakon (Don’t Frown))

Yes, I know what you mean. It’s kind of like the arbitrary use of the term ‘Islamic’ to label things like art and architecture (and even cuisine, believe it or not). By misleadingly throwing around such terms, one negates and denies the contributions of so many diverse and unique cultures and peoples, and gives the impression that, first, the only thing that defines them is religion, and second, that they all belong to this one homogeneous land. I mean, were Warhol’s screens shining examples of Christian art? But, as you said, it dumbs things down and means people have to do less thinking and questioning. Now, forgive me for being foozool, but … are you really foozool? I’m assuming your pseudonym isn’t a homage to an Arani poet (i.e. Fuzuli).

Hah! My mom and nana would call me that, mostly jokingly, while growing up. The word gets thrown around a lot in the house.

I used to be called that quite a few times as well, as a kid … in addition to other things! Lara, I love how you’ve blended Persian music with other genres in your mixes. You take one from the club to the chelo-kababi in a matter of minutes.

Kind of like how mom would switch between CDs, cassettes, and radio stations in the car. She’s probably my favourite DJ.

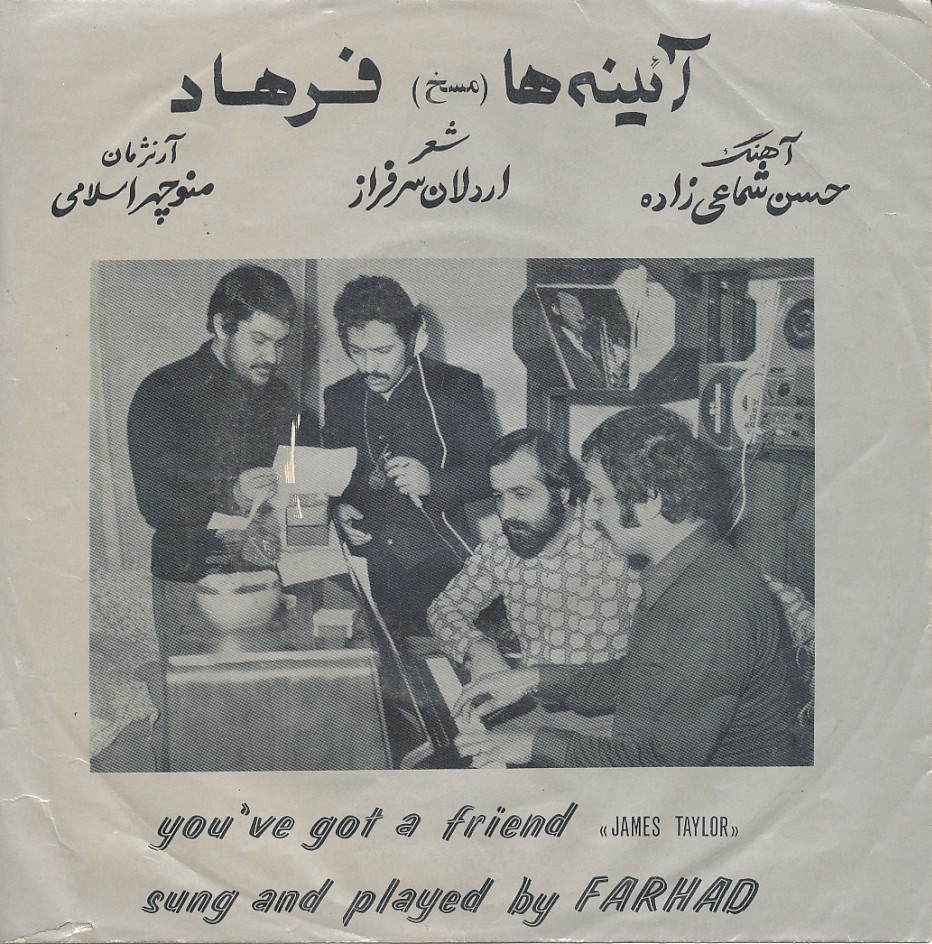

Who wouldn’t want a friend like Farhad? (A single featuring the songs Ayeneh ha (Mirrors) and James Taylor’s You’ve Got a Friend)

Now, to change ‘channels’, as we say in Persian: tell me a bit about this Armenian Genocide project you’re working on. It sounds fascinating.

I’m currently working with director and producer Bared Maronian of Orphans of the Genocide on producing a story and doing research for his upcoming film, Women of 1915. I had originally linked with Bared a few years ago, when I sent over material from some digital archiving work I’d done with the Embassy of the Republic of Armenia to the Kingdom of Denmark while studying abroad in Copenhagen for a semester. A Danish archivist in a village in mainland Denmark had a bunch of unseen materials relating to the Armenian Genocide, stored in the basement of an elementary school: collodian-processed photographs, film reels, newspapers, etc. These had been passed down from Scandinavian missionaries who had witnessed the events, such as Karen Jeppe. It was a pretty surreal and meaningful experience being among the first people to see and touch these materials. I had no idea I would find Armenian stories scattered all the way to what almost felt like the middle of nowhere in Denmark. One of the Embassy assistants’ word stuck with me: ‘you never know what untold stories there are in these photos and reels. What’s sitting in front of us now has the potential to change so much’. I think that’s when it started to sink in.

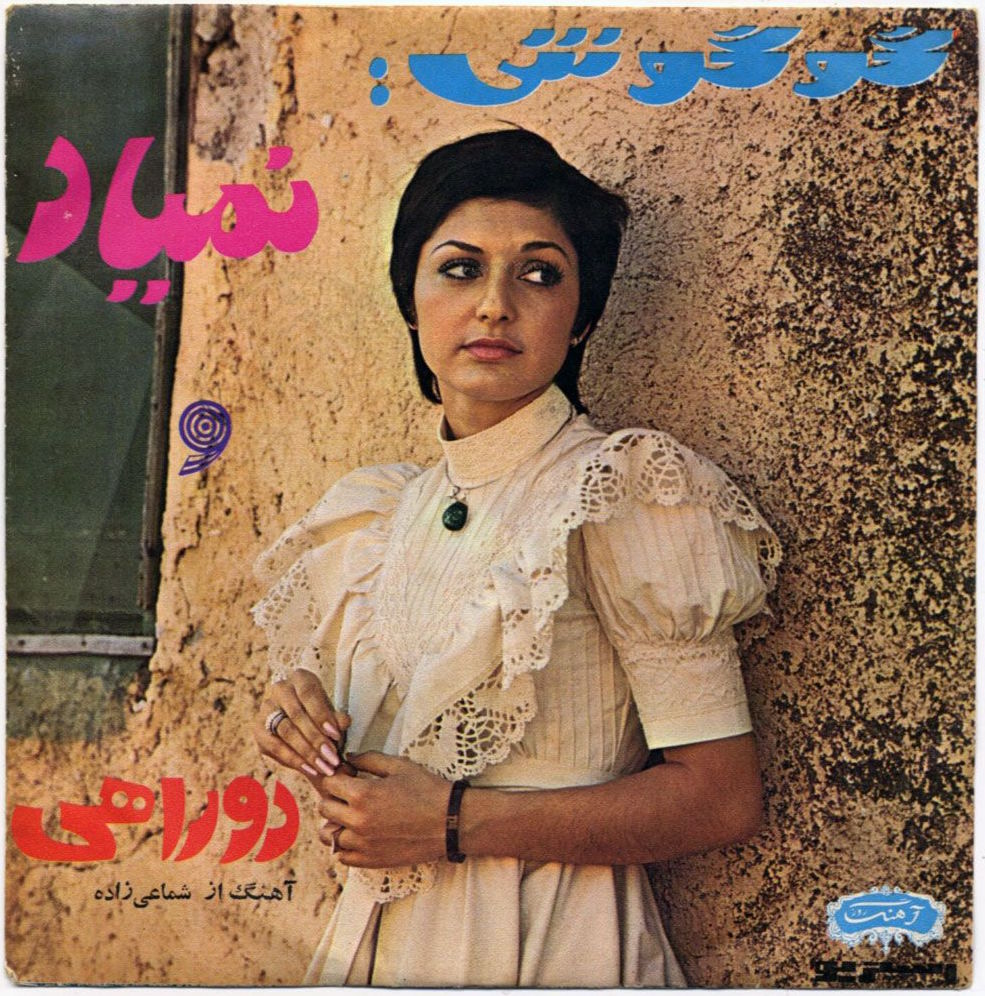

He ain’t comin’ … (A Googoosh single on the Ahang label featuring Nemiad (He Won’t Come) and Dorahi (Intersection); courtesy Shahre Farang)

And what about your collaboration with Esra Canoğullari? That an Armenian is collaborating with a Turk has seemed to dazzle some people.

Esra (8ULENTINA) and I started collaborating musically a little over a year ago. Esra has been teaching me a lot about DJing and mixing (it was Esra who lent me the turntables to make this mix!), and we had initially connected as interdisciplinary artists who both used sound and video for storytelling. Esra has been a mentor figure for me in so many ways. We started curating and DJing a little over a year ago with our first series of events, Night Forms (in collaboration with Browntourage), and eventually began running our monthly events (Club Chai) in a warehouse in Oakland. Club Chai has become a platform for people – typically with transnational stories and identities – to tell stories through sounds and multimedia. As Esra says, we ‘put traditional percussion and Eastern sounds with club music, and let people see how those two things can exist in the same space’.

I think our ethnic identities have been an important part of our work together. We acknowledge the violent histories and current political conflicts between Turks, Armenians, and Kurds, and conversations naturally end up happening around our work, or stemming from family stories and news we hear about. You can’t ignore talking about these things, especially when they’re all still completely relevant today as well as very personal and a part of our histories. Esra and I bonded over being artists with work related to our diaspora narratives. Although there is acknowledgment and dialogue constantly happening between us, we are not a representation of solidarity between our communities and the reality of the situation out there. There is so much work, recognition, and dialogue that needs to happen that goes beyond individual collaborations, and instead extends beyond many generations of communities.

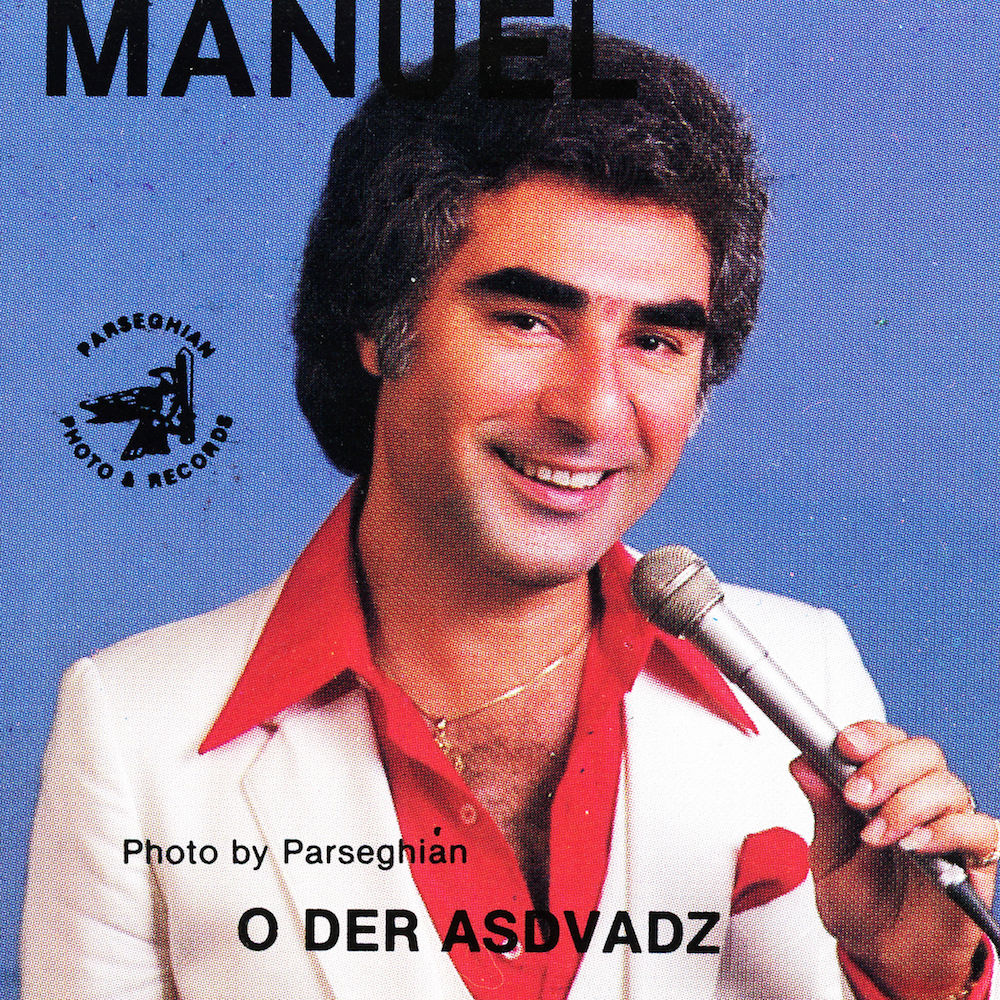

Killer collar (Manuel Menengichian’s O Der Asdvadz (Oh Dear God) on the Parseghian label)

On account of your pseudonym … is there anything you’ve been wanting to ask me?

You once told me about an encounter you had with the Armenian director Atom Egoyan. How did you meet?

It was during a dinner with Abbas Kiarostami and the people at the Aga Khan Museum here in Toronto a few months ago. I didn’t get to talk to Atom during the dinner itself, but as he was leaving we enjoyed a brief chat. He had, many years ago in 2005, attended the Encyclopaedia Iranica gala in Toronto chaired by my mother, but I knew little about him then. It was great to finally meet him. I don’t know whose specs were cooler – his, or Abbas’.

Check out Lara’s latest project, a collaboration with 8ULENTINA, on Soundcloud.