Rediscovering Orhan Pamuk’s Snow in a sleepy town on the Turkish-Armenian border

The flight from Istanbul to Kars swings over the Black Sea in a long arc, finally descending below the clouds near the icy mountains north of Erzurum. When I peered out the airplane window, the terrain was completely frozen, except for where a few rocky ridges emerged through the snow. Glimpsing the snow blanketing the landscape was a shock, even though I knew I was bound for the coldest part of Turkey. Until I saw this, I always thought the characterisation of Kars as a remote border city was a bit of an exaggeration. However, looking around from the tarmac and seeing nothing but wisps of ice blowing across the plain to herald our arrival, I began to think I might have been wrong.

When I told friends I was going to Kars during a winter vacation, their responses ranged from confused to downright concerned. ‘Why Kars?’ some asked, taken aback. ‘It’s very cold,’ others warned, ‘and the flight takes almost two hours’. I struggled to come up with a satisfying explanation for why I was going: ‘there’s a book by Orhan Pamuk that takes place in Kars in the span of three days’, I told them. However, this seemed a little odd; why brave the cold in February to go to a small city on the Turkish border with Armenia because of a book that came out over 15 years ago? Most of the time, I opted for an easier answer: ‘I want to see the ruins of Ani’, I would reply – which was true. Yet, the trip was primarily an investigation into why Pamuk chose to stage his most political novel to date – and the one that undoubtedly contributed to his winning the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2006 – in this city.

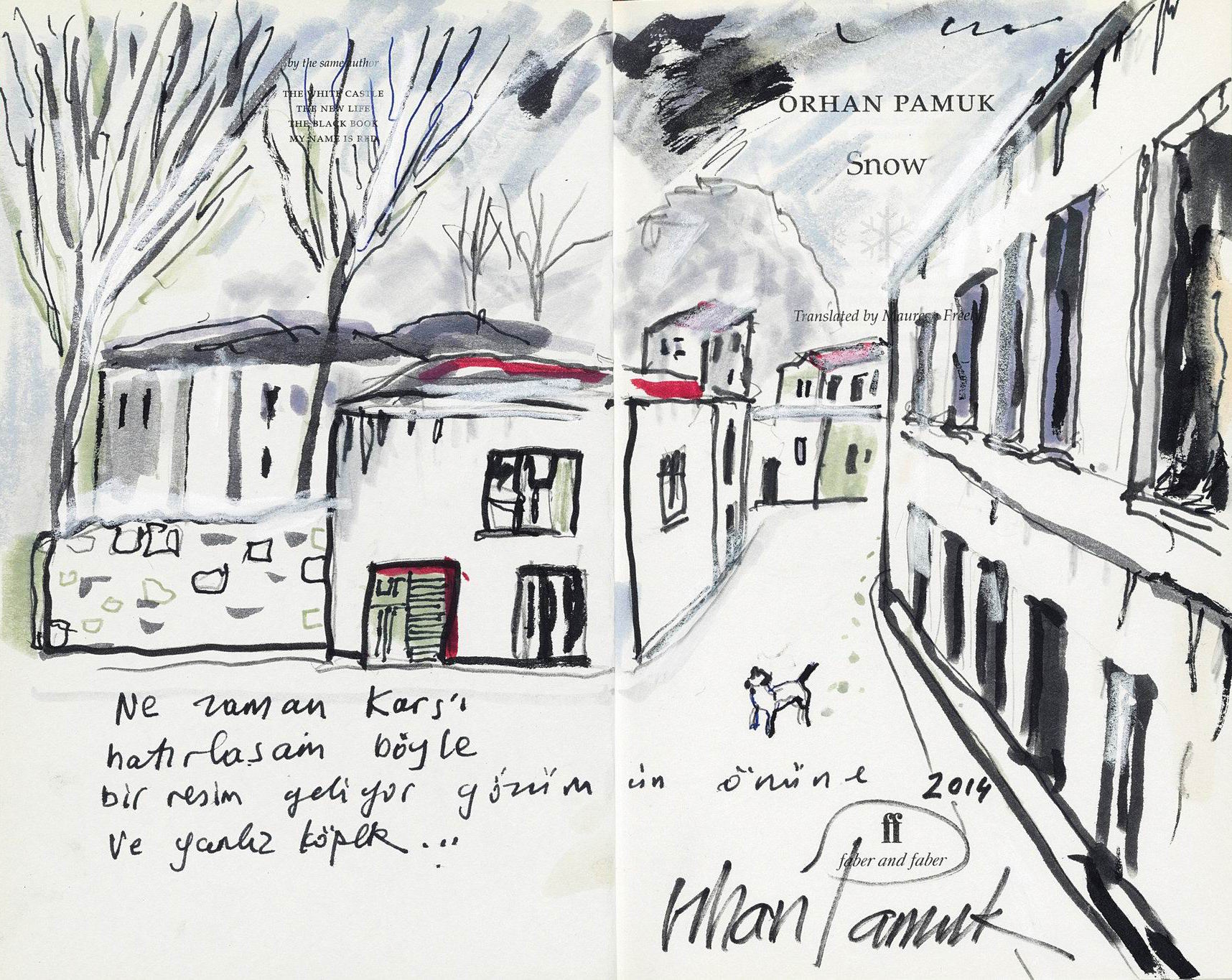

A drawing by Orhan Pamuk for the first edition of Snow

Pamuk has, in all fairness, answered my question before. He chose Kars because it is one of the coldest – and poorest – cities in Turkey. Pamuk wrote in his field notes from Kars, contained in his collection of essays, Other Colours (Oteki Renkler), that he knew his novel was ‘made of the stuff of the city, of its streets, inhabitants, trees, and shops, and even some of its faces’. However, he also acknowledged that the Kars of Snow (Kar) is not the real Kars. ‘This is partly because I did not write the novel to replicate the city’, he wrote; ‘I wanted to project onto Kars my own sense of the city’s atmosphere and the questions it posed to me’. In turn, I wanted to see if, by following in Pamuk’s footsteps and by talking to the people of Kars, I could find out two things: one, what questions Kars posed to Pamuk back then, and two, what Snow had to say nearly a decade and a half after it was published.

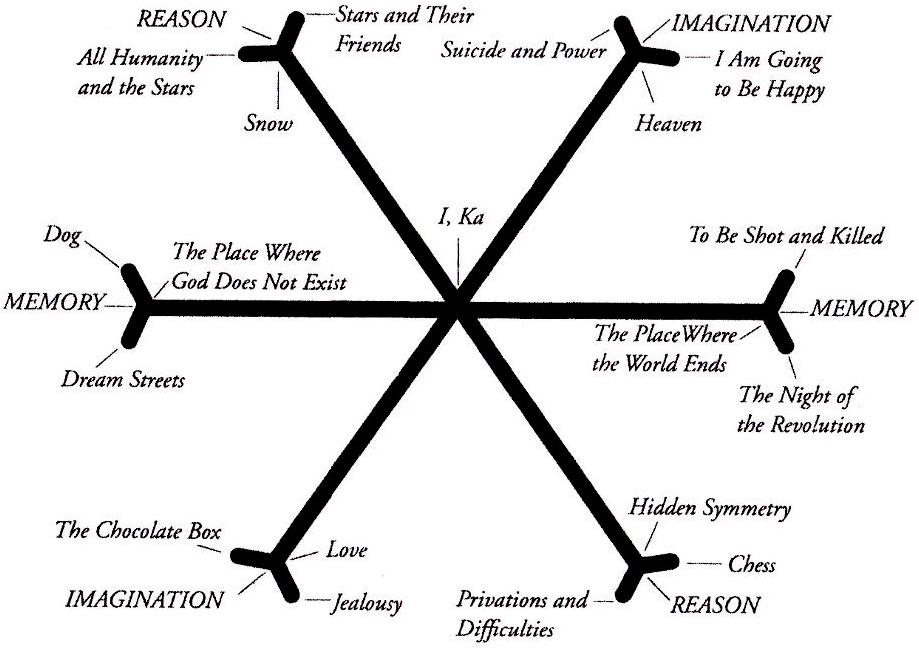

After returning to Turkey after 12 years of political exile in Germany, Pamuk’s protagonist, Kerim Alakuşoğlu, travels to Kars to ostensibly cover for an Istanbul newspaper a spate of suicides among girls wearing the headscarf. In reality, Kerim is more motivated by the memory of a former classmate – the beautiful İpek – who now lives in Kars. A poet of middling success, Kerim goes by his initials, K.A., stylised as ‘Ka’. Over the course of three days in Kars, Ka reunites with İpek and is drawn into a world populated by Islamists, Kurds, staunch secularists, and everyone in between. In the meantime, Ka is struck by an inspiration from God (or, the bleak and interminable snow that cuts off all roads and traps everyone in the city) to write a series of great poems.

A diagram from Snow

Though he is often spoken about as a writer dealing with a ‘clash and interacting of cultures’ (according to the Nobel Committee), Pamuk has argued that he is not, in fact, interested in an essentialising binary of East and West. Nonetheless, this clash and interaction are central to many of his books, particularly Snow. ‘I think especially in Snow,’, says Esra Mirze Santesso, Associate Professor of English and Department Associate Head at the University of Georgia, ‘you have a wide spectrum of religious and political affiliations, and it becomes very difficult to pinpoint exactly where characters fall if you have to have a categorical identity’.

Sure enough, the characters in Snow evade any easy categorisation, their inner motivations being hard to pin down, even for readers familiar with contemporary Turkey. Kadife, İpek’s sister and a leader among the young women wearing the headscarf, is far from the ‘fundamentalist’ or ‘voiceless’ person her secular opponents accuse her of being. She is courageous and principled, and firmly believes that the government should have no say whether or not a woman should wear the headscarf, and whether it is a symbol of faith or a display of independence in a secular state. Similarly, the terrorist Blue emerges not as a cut-and-dry villain, but a silver-tongued and charismatic figure whom Ka secretly envies. Sunay Zaim, a bloviating actor who believes he is defending secularism, becomes a small-time revolutionary in a frightening hybrid performance piece and coup d’état. And, finally, sympathetic impoverished youths who admire the militant Kurdish organisation in Kars explain their rationale for Kurdish nationalism and are arrested in Zaim’s performance-cum-revolution. An epigraph by Robert Browning sets the stage for the politics of Snow: Our interest’s on the dangerous edge of things. The honest thief, the tender murderer, the superstitious atheist.

A young Orhan Pamuk as an architecture student and avid painter in Istanbul

These multifaceted, slippery characters, and the spectrum of Turkish religious and political positions they voice make Snow Pamuk’s most political novel to date. Religion, rebellion, and the Other are all at play, with Kars serving as a microcosm of the issues buffeting Turkey at large. Because of his Nişantaşı upbringing, and the fact that many of his books take placed in Istanbul, some have doubted whether Pamuk actually ever visited Kars. It seemed impossible to me, however, that he would throw a dart at a map of Anatolia and choose any city or town; moreover, Pamuk has written extensively about his time in Kars in Other Colours.

* * *

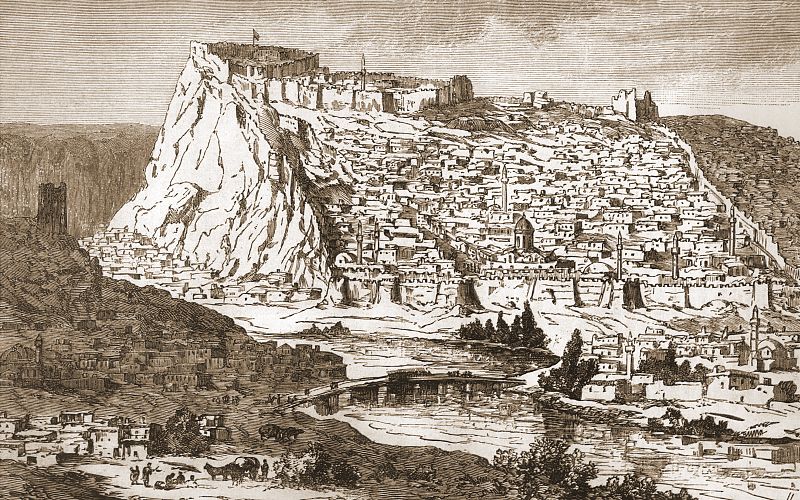

At the top of Kars Castle (Kars Kalesi), a 12th century basalt outpost, any doubts I had about Pamuk visiting the city were whipped away by the gusts of wind shrieking past the outer wall of the dark-grey fortress. The view from the top looks down on precisely the scene that Ka describes within the novel’s opening chapters: snow covering the ‘Seljuk castle and the shanties that sprawled among the ruins’. Ka has tears in his eyes when he realises that Kars has been buried in snow, and that he is the only one to notice its effacement. The same snow was then piling up on corrugated tin roofs below the castle. I pulled my coat tight against the cold, and, shivering, tiptoed through the mud on the way down the hill.

An early 20th century drawing of Kars Castle

Because of its position at one of the crossroads of Asia Minor, Kars has been home to several cultures and empires over the centuries. In the 10th century, Kars was for a time the centre of the Armenian Bagratid Kingdom. The castle Pamuk summited was later built when the Turkic Seljuks gained control of the region. From 1878 until the end of the First World War, Kars was a part of the Tsarist Russian Empire as a result of a territorial concession made by the Ottoman Empire after its defeat in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78. The Russians built the city on a grid, and began constructing regal, yet chilly stone houses that still bookend the streets in the old neighbourhoods. The Ismet Pasha Primary School is in one such neighbourhood, standing as a beautiful Russian stone mansion towering over nearby low-slung houses with cracked windows. When Pamuk visited Kars to write his novel, he strolled through this building with a photographer friend, peering into classrooms and exchanging hellos with teachers. After the end of the First World War, Kars changed hands to become a part of the new Republic of Armenia, (which acquired it after the Ottoman defeat), and then, shortly after in 1920, Turkish nationalist forces captured the city during the eastern campaign of the Turkish War of Independence.

Some of the calling cards foreign powers left behind in Kars are easy to miss. On my way back from Kars Castle, I had to step gingerly across the ice that had gathered on the dark cobblestone sidewalks of Faik Bey Street – cobblestones that had been laid by the Russians when they governed the city. I also found another memento left behind by a long-gone empire that I couldn’t get out of my head, even though my best instincts told me it was probably unrelated to Pamuk’s book. It lies in ruins, 45 kilometres east of the city; but the way it loomed in my mind, it could have been next door to Kars Castle or Ismet Pasha Primary School.

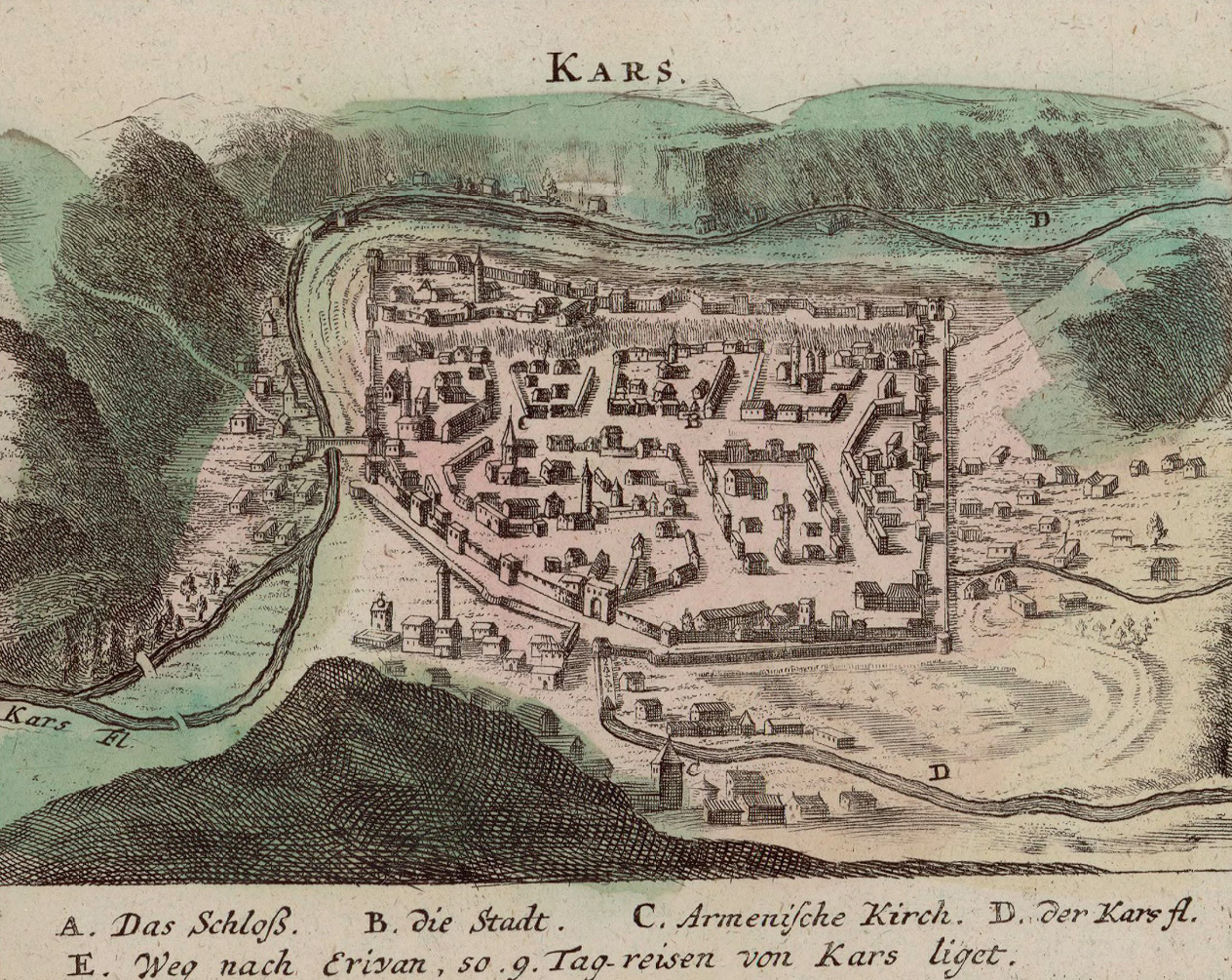

A 17th century illustration of Kars by Joseph Pitton de Tournefort

The only way to get to Ani is by arranging for private transportation. I was still 15 kilometres away from the ruins of Ani when the road, potholed from years of freezing and thawing, claimed our car’s front tire. Ali Gönel, the driver who had agreed to take me to Ani, swore and slammed his palms against the steering wheel. ‘What great luck of ours!’ he muttered under his breath. Moving at a crawl, we inched into a village in a halfhearted attempt to borrow a tire pump. A first attempt to get assistance ended with nobody being home, and a dog that looked more like a grey wolf lunging, teeth bared, at my car door. Thin trails of smoke rose up through the frigid February air from dilapidated cement houses and the roosters and geese patrolling the yard.

Making small talk while waiting for assistance, Ali mentioned he was in his final year studying graphic design at the local university, and that while he had visited Germany a while ago, he wanted more to visit the US someday. He asked me about the most beautiful places. I shrugged and suggested California and the Rocky Mountains in Colorado. When Ali told me that hardly anyone visited Kars, I mentioned Snow and its popularity in the States; he nodded wordlessly. We flagged down another car heading to Ani, filled with amiable skiers from Istanbul, and I got in. Ali, waiting behind in his car to wait for a spare tire, shrank in the rearview mirror amid the rolling snow-covered hills.

The Armenian church in Kars

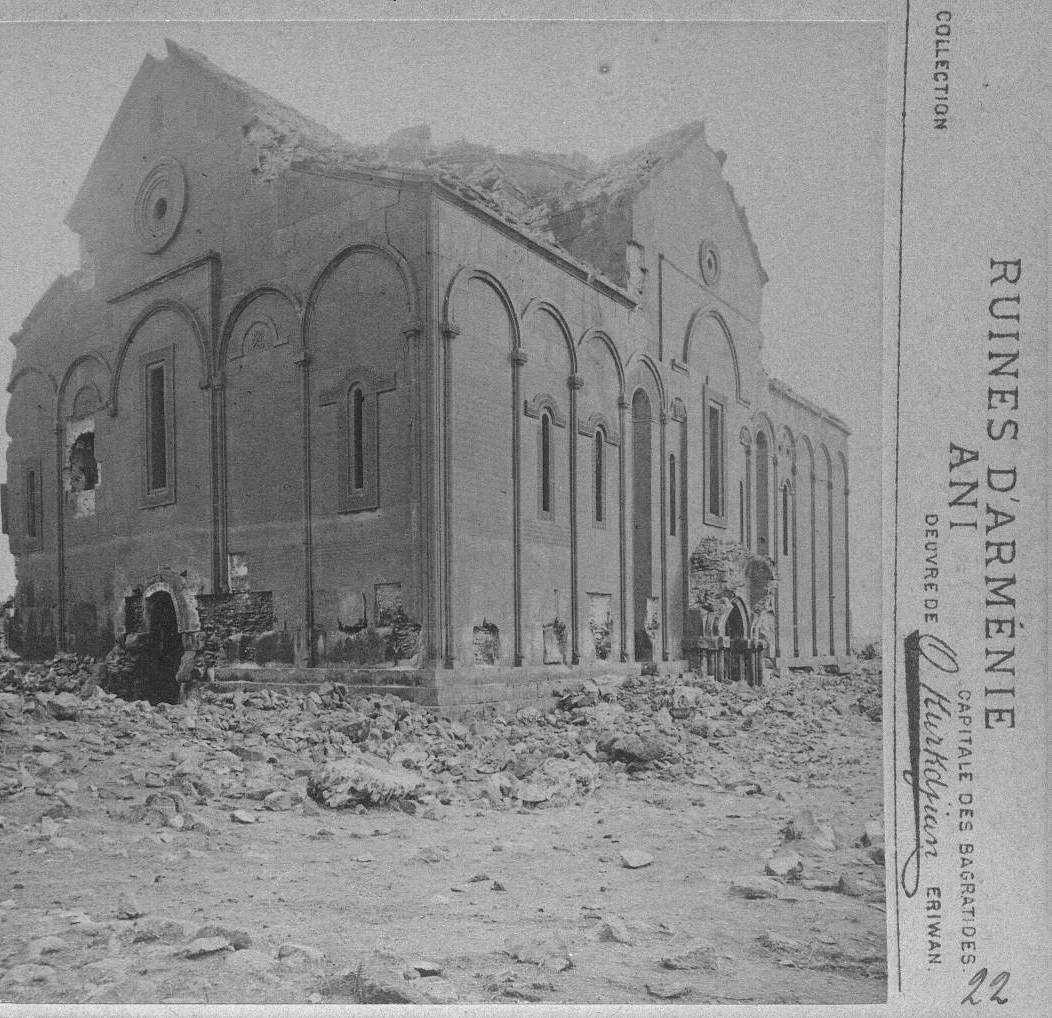

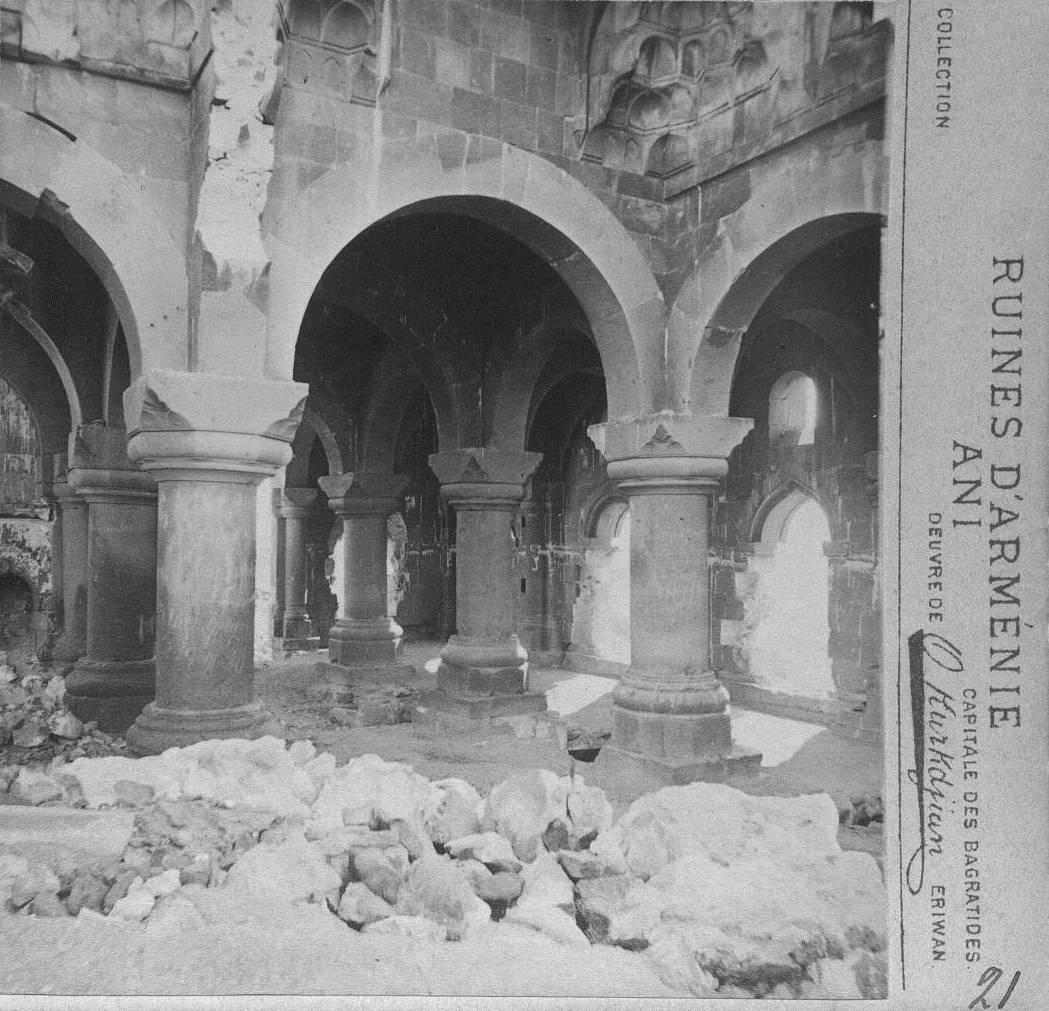

What remains of Ani is a handful of melancholy, reddish-brown basalt churches that watch over a plateau adjacent to the ravine separating Turkey from Armenia. The silence, combined with a view of solitary, deserted churches standing alone on the plateau, makes for an eerie walk through what was once a bustling medieval city, home to as many as 100,000 people in the 11th century. Now, all that remains are ghosts whispering in the naves and apses of the abandoned Armenian churches.

Although the ruins don’t appear in Snow, Ani throws into sharp relief the ideological cleavages Pamuk explores in the novel

Peering cautiously over the edge of the cliff, where the churning Akhurian River 20 metres below marks the border, I could make out steel Armenian watchtowers through the fog on the other side. The land border between Turkey and Armenia has been closed since 1993, when a territorial dispute between Armenia and Azerbaijan (The Republic of) led to Turkey cutting off all official relations with its northeast neighbour. Armenians take great pride in Ani as the capital of a bygone Armenian kingdom; however, the Turkish government’s treatment of the historic plateau has caused outrage on the other side of the border. Armenians, as well as most outside observers, have criticised Turkey for barely acknowledging the site’s Armenian legacy, leaving the ruins to crumble, and turning a blind eye as Ani’s priceless monuments fall prey to vandals and looters. Although the ruins don’t appear in Snow, Ani throws into sharp relief the ideological cleavages Pamuk explores in the novel; and, one may argue that Kars’ proximity to the ancient Armenian kingdom may have served as an oblique reference to identity and the Other.

A photograph of ruins in Ani taken by Ohannes Kurkdjian in the late 19th century (courtesy Wolfgang Wiggers and VirtualAni)

To hear from someone who understands how such identity issues affect life in Kars, I visited the office of Kars’ Serhat (Border) Radio and Television station. When I walked to the chairman’s office, it had been snowing heavily minutes earlier, but I could see the blue sky through the clouds for the first time since my arrival. Alican Alibeyoğlu, the Chairman of the station that appears by name in Snow, introduced Pamuk to the city 15 years ago. ‘When Orhan Pamuk came to Kars, he didn’t say anything about the novel’, Alibeyoğlu told me through a translator. ‘He said, “I am writing an article about Kars”, and we didn’t know anything about the novel; we showed the places that are in the novel to him.’ Pamuk merely flashed a press pass from Istanbul’s Sabah (Morning) newspaper, and because Alibeyoğlu was assisting Pamuk, he got to spend time with him. ‘He loves omelettes’, he told me, laughing. In Snow, Pamuk’s fictional residents tune in to Alibeyoğlu’s station to hear about the latest events in their city.

Alibeyoğlu explained how the driving action of Snow – a series of suicides among young women in Kars who wear the headscarf – actually took place in Batman (a unit of weight in Turkish, not to be confused with the masked superhero), another eastern Turkish city. Nevertheless, despite the transplanted events, Alibeyoğlu said an economically-depressed city being able to lay claims to a world-famous novel outweighs any inaccuracies. ‘It is a really good advertisement of Kars, because [Pamuk won] a Nobel Prize with the help of [Snow]’, he said. ‘[Whether] it is a good advertisement or a bad [one] is not important; it is an advertisement for Kars … even if [Pamuk’s story] is not accurate.’

An early 20th century photograph of Kars

Alibeyoğlu believes setting the novel in Kars was Pamuk’s attempt to experience life outside cosmopolitan Istanbul. ‘[He] was curious about this region of Turkey because he had lived his whole life in Istanbul, or [western] Turkey; maybe he didn’t know anything about eastern Turkey or Kars’, Alibeyoğlu told me. ‘There are 32 different nationalities in Kars. Kars is a political centre, and there is political tension here. Maybe that’s why it made him curious.’ This tension manifests itself mainly in the discussion surrounding the closed border with Armenia. I asked Alibeyoğlu whether the relationship between Turkey and Armenia might improve in the future. ‘Of course’, he responded. Why? Because ‘bad things are not going to last forever … [The Republic of] Azerbaijan and Armenia will have good relations in the future’, he explained. ‘Turkey is doing this because of Azerbaijan, and when they have good relations, this is not going to be Turkey’s problem.’

The Alibeyoğlu family has worked tirelessly to improve Turkish-Armenian relations in its border city. Alibeyoğlu has initiated joint broadcasting projects with Armenian television stations. His brother, Naif, was the mayor of Kars between 1999 – 2009, and a member of the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP). In 2006, Naif commissioned the Monument to Humanity, Mehmet Aksoy’s sculpture of two towering, solemn stone figures reaching out to clasp hands with one another, intended to symbolise an end to conflict in general. Yet, the reference to Armenia was clear, and on a trip to Kars, then-Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan excoriated the monument, and was joined by nationalist residents as well as locals originally from the Republic of Azerbaijan. In 2009, Naif was dismissed from consideration as an AKP candidate for mayor, and the sculpture, in turn, was demolished in 2011. ‘The sculpture was really important for our family, for me, and for my brother’, Alibeyoğlu told me. ‘Kars is a poor city, but people in Turkey are getting used to [hearing] news about Kars with the help of Pamuk’s novel and different things, like the sculpture.’ Aksoy, the sculptor, hopes to reconstruct his piece in the near future.

Mehmet Aksoy’s destroyed Monument to Humanity (courtesy AFP)

Symbolism aside, an easing of tension with Armenia is more than an ideological matter for Kars. According to Alibeyoğlu, economic problems are the main concern for Kars’ residents, and are inextricably linked to the closed border. ‘If we open the border, we are going to have millions of tourists from other countries, which will be good for Kars’ economy’, he said. ‘Most of the population of Kars went to other cities in Turkey, like Istanbul, because of economic problems. If we solve [them], they are going to come back.’ Opening the border will also cut the grueling 550 kilometre land journey to Yerevan through Georgia to a mere 170, spurring on trade and giving Armenian tourists easier access to the ruins of Ani and other heritage sites.

Snow did not endear Pamuk to everyone in the city; but, then again, Alibeyoğlu reminded me, not everyone in Kars may be familiar with the book’s plot. ‘I think most of the people in Kars [haven’t] read the novel’, Alibeyoğlu admitted. I asked Ismet Gönel (Ali’s father, and my taxi driver; ferrying me around the city was a family affair) what Kars’ residents think of Pamuk. In his brown knit sweater and with an easy smile, Gönel gave a knowing laugh when I brought the matter up. ‘Some people like him, some people don’t’, he said. ‘I like him’, Gönel told me; ‘he is a good man, and he writes about what Turkey is really like – does he not?’

Ruins in Ani photographed by Ohannes Kurkdjian in the late 19th century (courtesy Wolfgang Wiggers and VirtualAn

Pamuk closes his book with a reference to the dilemma of representing Kars in a novel, particularly to an audience of outsiders. On the last page, a Kars resident has a conversation with Orhan, Pamuk’s narrator and fictional stand-in:

‘I did think of something, but you may not like it,’ he said. ‘If you write a book set in Kars and put me in it, I’d like to tell your readers not to believe anything you say about me, anything you say about any of us. No one could understand us from so far away.’

‘But no one believes in that way what he reads in a novel,’ I said.

‘Oh, yes, they do,’ he cried. ‘If only to see themselves as wise and superior and humanistic, they need to think of us as sweet and funny, and convince themselves that they sympathise with the way we are and even love us. But if you would put in what I’ve just said, at least your readers will keep a little room for doubt in their minds.’

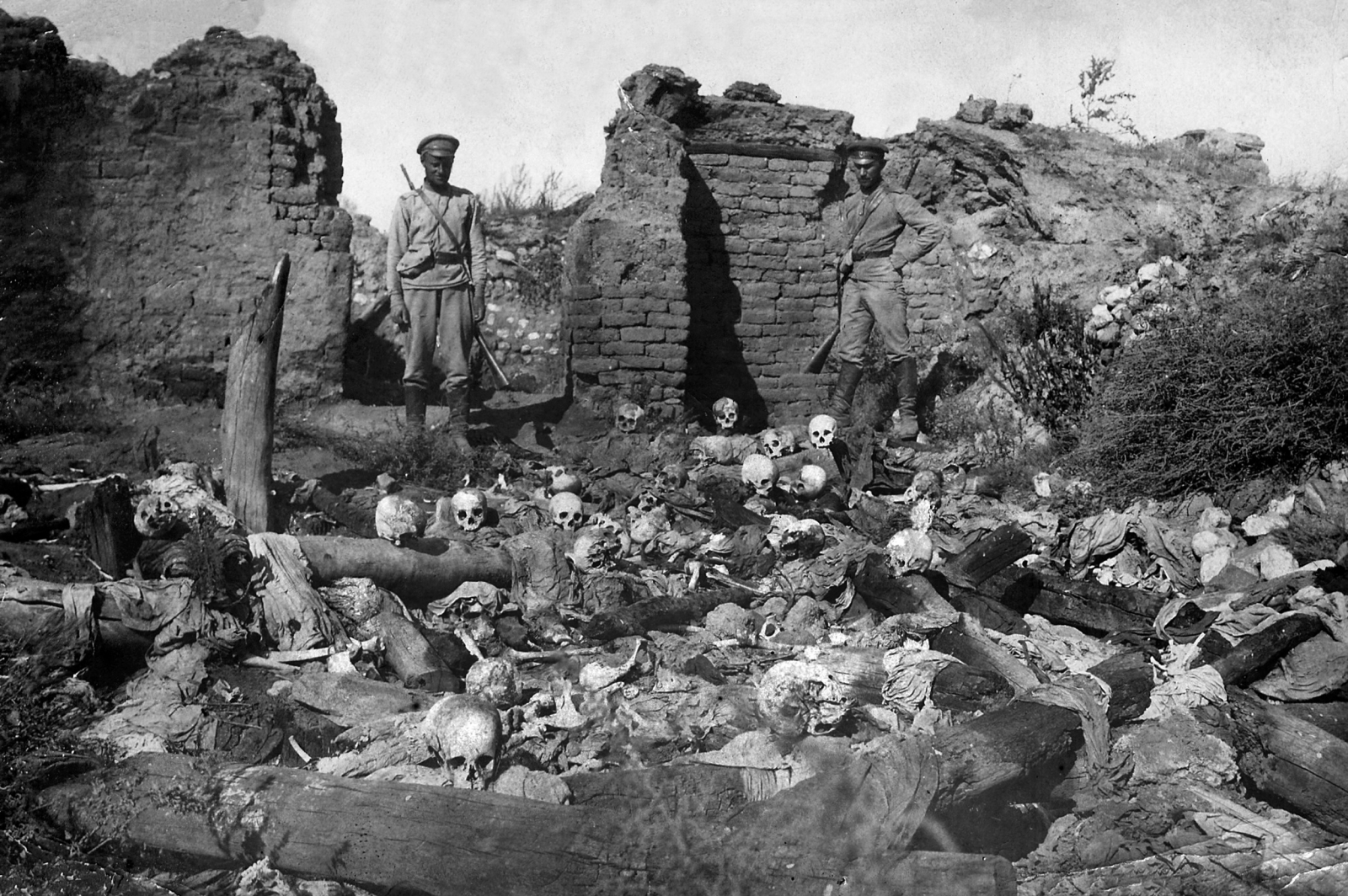

The multitude of voices present in Snow makes Pamuk’s case for expanding dialogue in Turkey without ever spelling it out. However, in the interviews and remarks following the book’s publication, the author pushed the boundaries of discussion more overtly. At a 2005 award ceremony in Frankfurt, the author said, ‘a Turkish novelist who fails to imagine the Kurds and other minorities, and who neglects to illuminate the black spots in his country’s unspoken history, will, in my view, produce work that has a hole at its centre’. The same year, Pamuk told a Swiss publication that one million Armenian subjects of the Ottoman Empire were, and 30,000 Kurds have been killed in Turkey, although ‘no one dares to talk about it’. The outcry that followed led to him leaving the country in self-imposed exile, and being charged with ‘insulting Turkish-ness’ (under Article 301 of Turkey’s penal code). The charges, however, were later dropped.

Turkish soldiers before the skeletal remains of Armenians in the village of Sheykxalan in the Mush valley in 1915 (courtesy the Armenian Genocide Museum)

Rereading Snow 15 years later, certain aspects of the book are prescient. In the same year that Pamuk published his novel, the conservative AKP won its first of many parliamentary election victories. As well, the laws that banned headscarves in Turkish schools were gradually lifted. At the same time, Pamuk’s idea of hearing the voices of others is more relevant than ever. Turkey has recently seen renewed violence in cities in the country’s predominantly Kurdish southeast, after a two-year ceasefire between the Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK) and the Turkish state broke down in July. In October of 2015, twin bombs killed more than 100 people in Ankara at a rally for a peaceful end to the violence between Turks and Kurds.

Instead of unity in the aftermath of a tragedy, divisions in Turkish society seem greater than ever before. In January, talk show host Beyazıt Öztürk of the popular Beyaz Show was pilloried by pro-government media outlets and accused of spreading terrorist propaganda after a caller from Diyarbakır brought up the issue of the continuing violence; Öztürk, his guests, and the studio audience applauded in response. A week later, two dozen academics from Kocaeli University in northwest Turkey were briefly detained for signing a petition that called for an end to civilian deaths in the clashes in the southeast. Similarly, among journalists and media outlets, opposition to the government is being increasingly seen as supporting terrorism, and has often resulted in the jailing of writers and editors: the antithesis of Pamuk’s heteroglossia in Snow. As Santesso puts it, ‘It’s one thing to be able to slap a terrorist designation to a character; it’s another to pursue and try to understand what it means to belong to that position’.

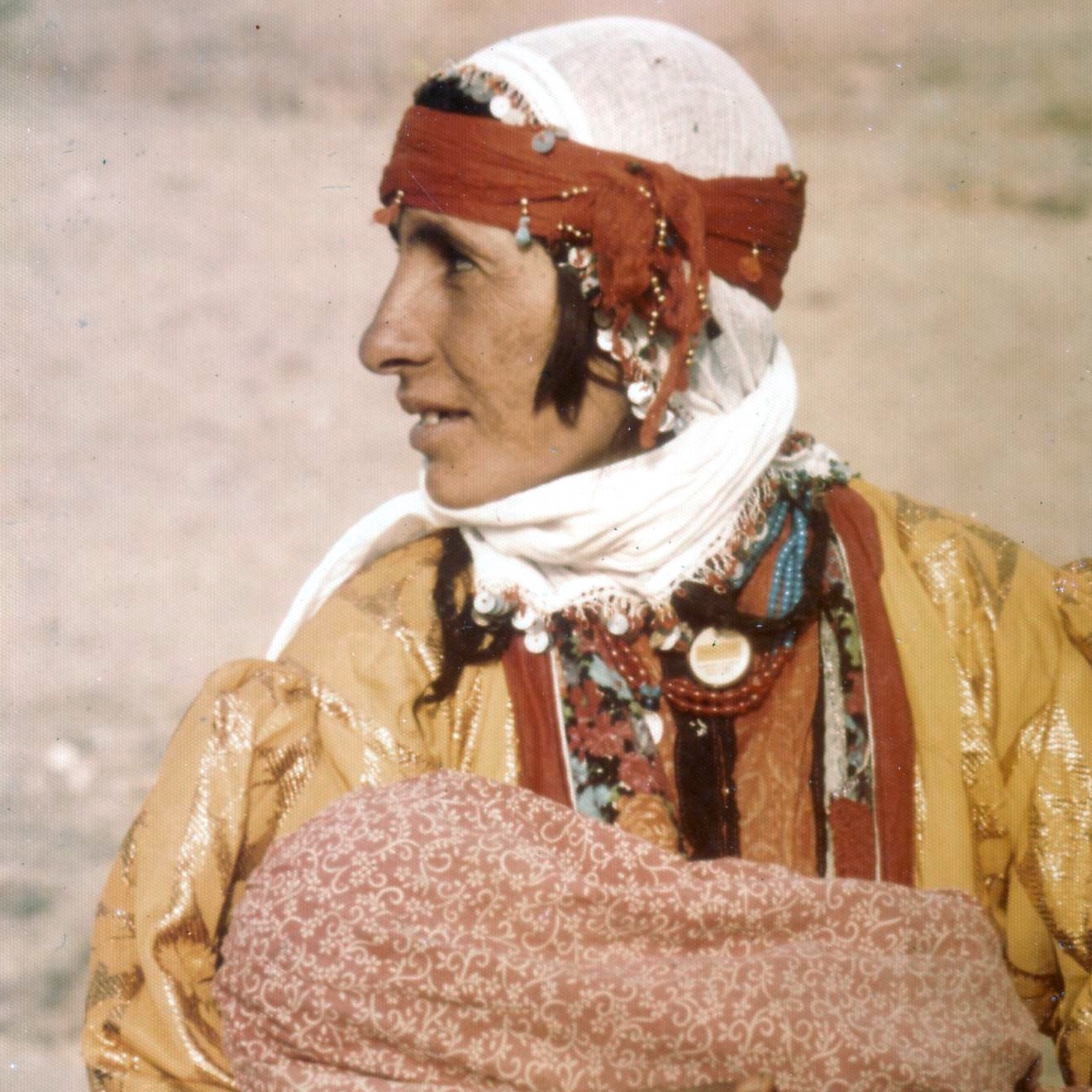

A Kurdish mother and child in Van in 1973 (courtesy John Hill)

Alibeyoğlu said he could see a disconnect in the minds of those living in western Turkey when they think about eastern Turkey. ‘In the west, people think that all Kurds want to divide Turkey, or that [they are] all terrorists’, he said. ‘But most of the Kurds in the east don’t want any division; they don’t want to divide Turkey into pieces, they don’t want to have a Kurdistan or something. They want to live together.’ The problem, according to Alibeyoğlu, lies in ignorance. ‘[Those in the west] don’t read anything. They don’t want to watch anything about the eastern side [or] see anything [having to do with] the people here’ – including the near-constant news documenting an increasingly destructive conflict between the government and the PKK. They aren’t, in other words, doing what Pamuk tried to 20 years ago.

On my last morning in Kars, I made a pilgrimage to where Pamuk wrote most of the notes and ideas that became Snow: the Kars equivalent of the hotel room in Istanbul where Agatha Christie wrote Murder on the Orient Express. It was clear and sunny, with none of the grey haze and snow flurries of the day before; but once I stepped inside the New Unity teahouse, my eyes had to adjust to the darkness of the wooden interior. It was 11 am, and the teahouse was packed; almost every table was full of old men with lined faces smoking, drinking tea, and playing cards, their canes resting around the round tables. Only a few people looked up when I entered, and I stood by the door for a minute to observe. Although I took out my camera to snap a photo, I thought better of it after a glare from the manager. I could imagine Pamuk writing his novel here; the teahouse’s interior was probably exactly as it was two decades ago. Pamuk told the Paris Review in 2005 that by the end of his stay in Kars, these men in the café had grown curious. ‘People were talking among themselves while I wrote some notes, saying, “What kind of article is he writing? It’s been three years, enough time to write a novel”. They’d caught on to me.’

The teahouse frequented by Pamuk during his stay in Kars (courtesy the author)

That afternoon, my bus left Kars and headed west under a cloudless blue sky. It was the same route that Ka took – albeit in the opposite direction. We cut through a frozen pass in between the jagged mountains towards Erzurum as the sun sank, stopping periodically so that a uniformed member of the gendarmerie could check our ID cards. There wasn’t a falling snowflake in sight.