From the steppes to swanky Stamboul - a glance at the history of women in Turkish music

It has only been in recent years that psychedelic Turkish music has begun to be perceived as a real treasure. Music collectors, musicians, DJs, and hipsters of all kinds in the West are expressing a love for the crazy sounds of Anatolia’s recent musical past, and I count myself amongst them. My friends and I share a fascination for the songs of the likes of Bariş Manço, Erkin Koray, Edip Akbayram, and Cem Karaca, with all their fuzzy guitars and surreal sounds of the Hammond organ. Perhaps this is because we can find some sort of connection between this music and that of 70s America and Western Europe. We find Anatolian rock to be a collage of the vintage American and European soundscapes we are familiar with, and an Oriental dream of mesmerising sounds we have been longing for. Our love is fed mostly by compilations as well as reissues of records, about which Joobin Bekhrad wrote extensively in his 2014 piece Farsi Funk, Bosphorus Beats.

I have always, however, wondered about female artists in Anatolian rock. Whenever I researched the subject, I mostly came across one name: Selda Bağcan. There were others, though, like Kamuran Akkor, who has also been recently discovered by Western record labels such as Finders Keepers and Light in the Attic; but what happened to the rest? This question and curiosity turned into an obsession, and I soon bought a ticket to Istanbul and took a month off of work to find my answers, taking with me only my portable turntable and recording equipment to dig into old vinyls and talk to people who might be able to help me.

Selda Bağcan’s self-titled 1976 album

As a record collector and cultural anthropologist, I have always been researching the influence of women in art and culture. Even though I have been researching music from various cultures as a whole – mostly produced during the 60s and 70s – I have largely focused on female singers and musicians, from American legends such as Nancy Sinatra to Italian mods such as Brunetta, Parisian yé-yé singers (e.g. France Gall), and Persian pop icons like Ramesh. These women around the world were the voice of a new generation. In the 60s, a social revolution was happening worldwide. As a result of civil rights movements in the US in the early 20th century and the efforts of the suffragettes, women gained more freedom to speak and perform, as well as vote. Decades later, in the 60s, a second wave of feminism would appear.

Female Ottoman musicians from the 16th century book Costumes de la Coeur et de la Ville de Constantinople

The situation was not so different in Turkey; only after the Republic was founded in 1923, it could be said, did ordinary women gain significant respect politically and socially. The followers of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk – the Kemalists – promoted civil rights, banned polygamy, and granted women equal rights in matters of divorce and child custody, in addition to allowing women to vote, among other things. However, in 1960, approximately one third of Turkish women were still illiterate, and mostly under the influence of old Ottoman values and norms. Many of these women had been raised and taught to be model wives and mothers, and guardians of traditional Turkish customs and virtues. Following Atatürk’s reforms, the hybrid nature of Turkey (Istanbul in particular) became more pronounced, and was well-reflected in many aspects of culture such as popular music. Sometimes in the domestic music of the 60s and 70s, Western sensibilities were more prominent, while at others, folk elements dominated.

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (in blue suit and white hat) and friends in the 1930s

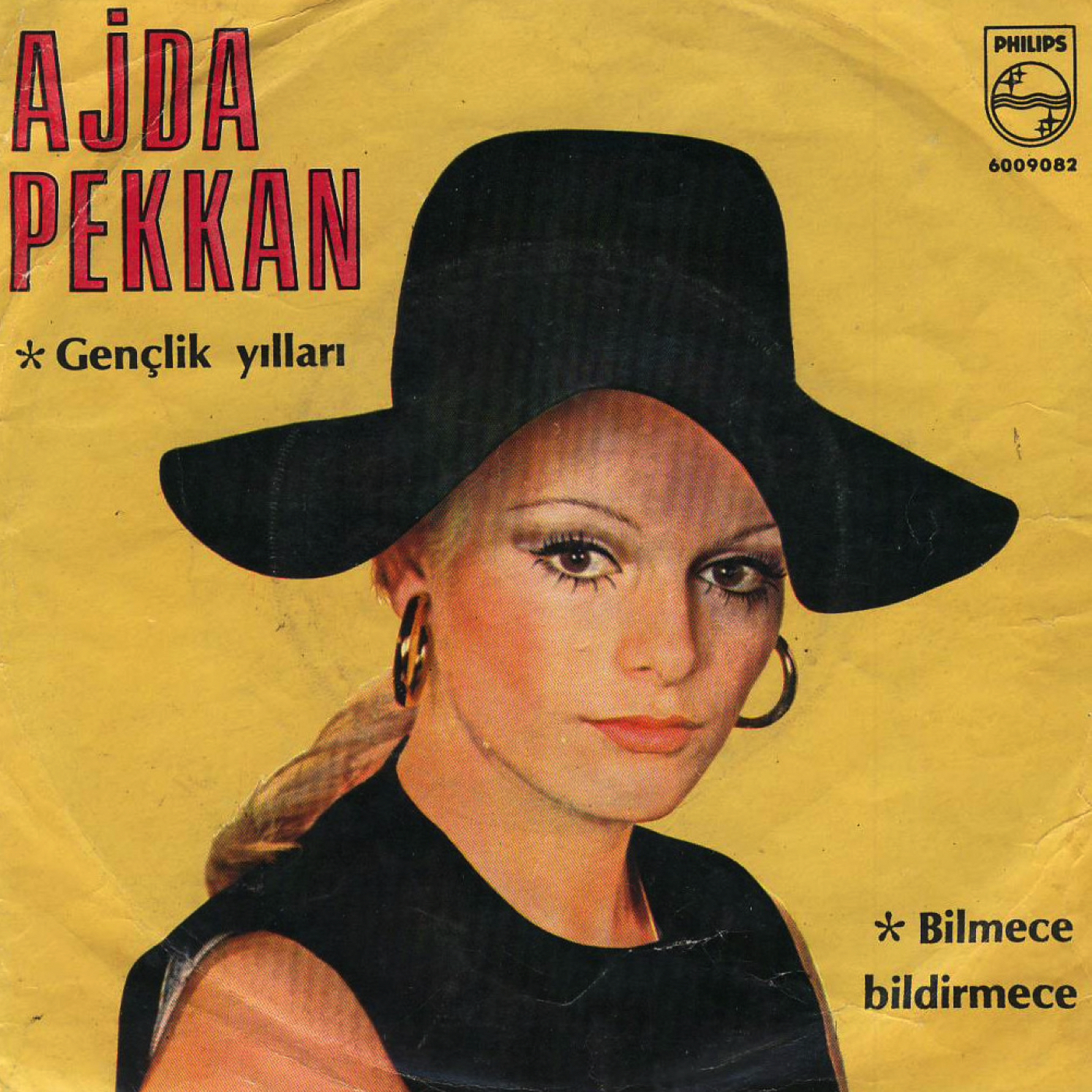

Blondes Have More Fun

The year is 1966. A 20 year-old Ajda Pekkan, a longhaired, blonde beauty, has just released her fourth single. The song, Moda Yolunda (On Moda Street) is a hit, reflecting everything hip and fashionable at the time. The lyrics tell the story of young and attractive men and women walking along a trendy street in Istanbul’s Kadiköy district, wearing chic clothes and chewing bubble gum. Many amongst the wealthy middle-class and bourgeois want to be modern – European, that is. Foreign-looking girls in miniskirts and high heels have the best chance of taking the spotlight. The more European they look, the more foreign their accents sound, and the more French or English songs they sing, the better. Ajda Pekkan has everything going for her, as does another notable pop singer, Füsun Önal, who has debuted with her cover of The Supremes’ My World is Empty Without You, Babe. Both have fans amongst the well-educated and ambitious women of Istanbul and Ankara, with their high expectations of social freedoms. For many, however, these dreams end the moment their fathers find for them the ideal husband.

I heard an interesting story recently from Özgür Erkök Moroder – an artist and director living in Berlin – that perfectly echoes this ‘pattern’. Özgür told me about his mother, who established a girl group in 1965. The Daisies were beautiful, modern, and sexy; they sang in French, and covered songs by France Gall and Marie Laforet. They had all been raised in wealthy and established Turkish families, were all very well-educated, and had many aspirations. Their dreams of showbiz and making it big in the music industry, however, fizzled out as soon as they married and settled into family life. The miniskirts were put aside, and, as Özgür said, they became exactly like their mothers and grandmothers before them, as if ‘nothing had ever happened’; their revolution came to an end.

Aşık, Arabesk, and sanat müziği were widely listened to around the country, as were their female exponents who spanned multiple genres and won the attention of audiences of all social classes and ethnicities

The swinging 60s are often looked upon as an era of the celebration of women’s rights around the world. Women were embracing their sexuality; but, they were also objectified and subject at times to overpowering male gazes. In Turkey, the issue was more or less the same. It was acceptable (and in many cases, encouraged) in major cities like Istanbul for women to appear on stage almost naked. As well, men controlled the music industry, financially as well as artistically; the majority of songs were written and composed by men. It is no wonder, then, that women were repeatedly objectified in them.

Here, kitty kitty: Figen Han’s 1977 Pisi Pisi (Kitty Kitty) single

Ex-Oriente Lux

Turkish music with abundant Western elements and ‘modern’ sensibilities was at once in sync and at odds with traditional music. While many middle-class Turks were looking for European connections, those in lower social strata mostly sought music that confirmed their identities and reflected their traditions, and that could not be expressed in any other language than Turkish. Music has always played a central role in Turkic culture, in which women have played no small role. Before Ottoman times, female musicians were prominent in Turkic society, and continue to be at the forefront in Alevi circles. According to Murat Ertel, leader of the well-known fusion band Baba Zula, female musicians were also integral to Turkic shamanism, in which they assumed the roles of healers and messengers of the unseen. Murat also told me how important it is to understand that the term ‘Alevi’ (Arabic for ‘follower of Ali’) can also refer to alev, the Turkish word for fire and light. To him, the term carries a message of hope and enlightenment.

With the influence of shariat law during Ottoman times, music was pushed to the fringe and injunctions were placed on the use of musical instruments. Musicians, however, prevailed in the end, and classical Ottoman ‘art’ music (sanat müziği) – the music of the urban ruling class – has to date been well-preserved. It was the Empire’s rural subjects, however, who preserved and upheld folk music (halk müziği and aşık müziği) and culture. Much later, an extraordinary blend of Egyptian film music, belly dance rhythms, and Arabic-style instrumentation and vocals captured the hearts of Anatolian immigrants in Istanbul. The culture of Arabesk (lit. ‘Arabesque’) emerged in the 50s and 60s when impoverished villagers from south-eastern Turkey relocated to Istanbul, and became increasingly popular following icon Orhan Gencebay’s 1972 album (and the film of the same name in which he starred), Bir Teselli Ver. In the 60s and 70s, music in Turkey began to become more and more available as a result of the growing music industry, as well as the popularity of mediums such as radio and film. Aşık, Arabesk, and sanat müziği were widely listened to around the country, as were their female exponents who spanned multiple genres and won the attention of audiences of all social classes and ethnicities.

Power to the People

Folk music in Turkey has been constantly celebrating its vitality. Old folk numbers and traditional music have remained vivid elements of Turkish culture up until today, and have been readapting themselves to changing times and climates. Scores of interpretations of folk songs exist from each decade. In the 60s and 70s, the Turkish music industry was exploding with variations and interpretations of classical, folk, and aşık (‘bard’, originally meaning ‘lover’ in Arabic) music. In order to feature indigenous and local sounds, contemporary musicians were dabbling with art and folk music. Sometimes, this involved the removal of Arabic elements that the Kemalists had also fought against. The singer Esin Afşar is perhaps a notable example of this trend. Born into a family of Kemalists, the educated and cosmopolitan Afşar chose to return to the roots of Turkish halk music. Supported by the influential musicologist and bağlama player, Ruhi Su, she quickly became recognised as a major folk musician. Like Afşar, many other female musicians looked back to tradition and folk culture. Artists such as Nurcan and Gulcan Opel, Nesrin Sipahi, Mürüvvet Kekilli, Rana Alagöz, and Yüksel Özkasap, for example, combined a fascination with halk and aşık music with modern and Western-influenced popular music.

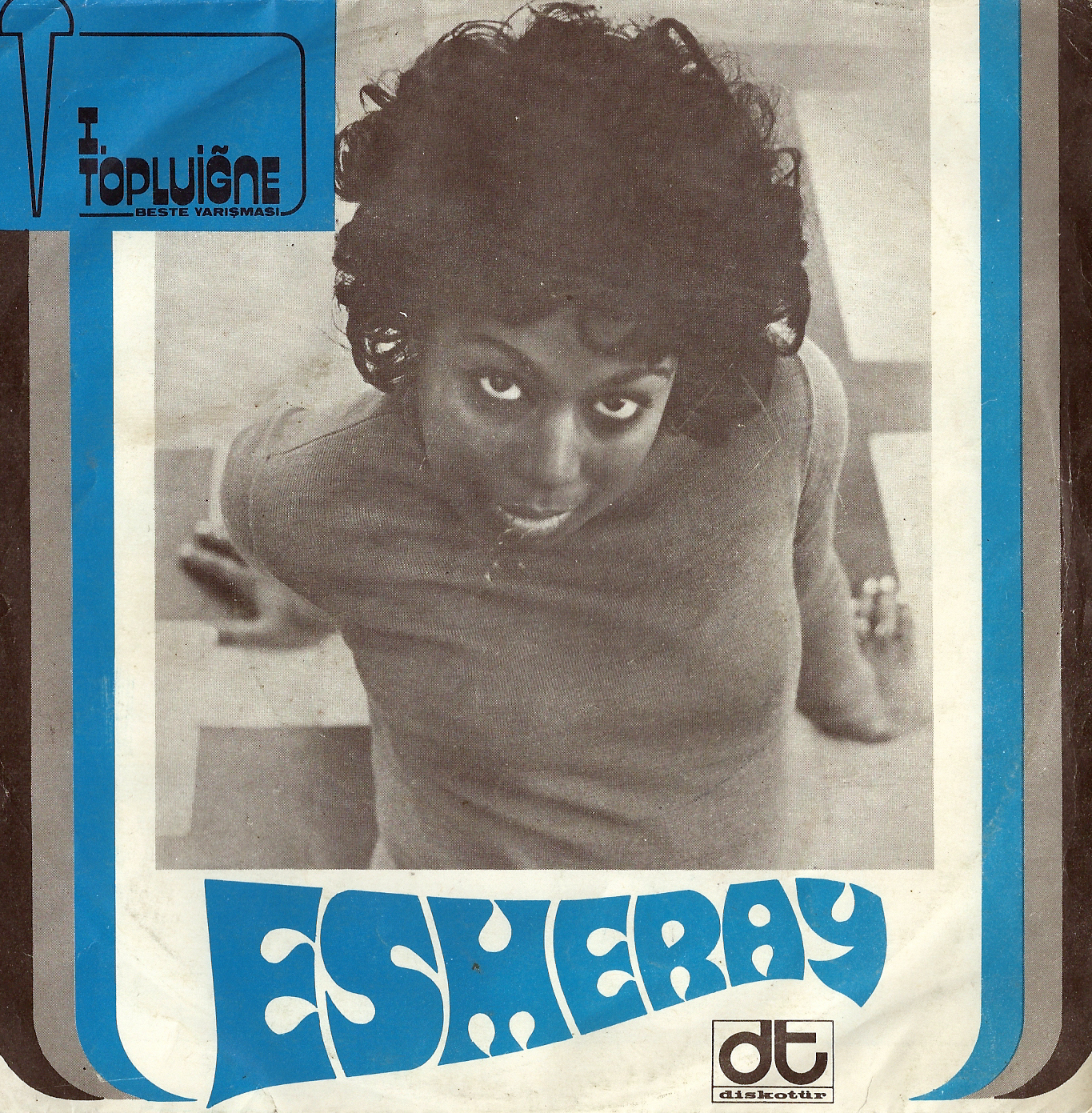

Esmeray’s 1974 single Unutama Beni (You Can’t Forget Me)

Turkish folk music, with roots partly in Alevi culture, provided musicians with an opportunity to express issues of freedom, injustice, and social discontent, just as was the case with folk music in the States at the time. Such songs, however, were not very common. Tülay German’s Burçak Tarlası, which told the story of a young bride forced by her mother-in-law to work slavishly in the fields was a turning point. A communist and civil rights advocate, German emigrated from Turkey to France in 1966 – the same year that saw hits by Ajda Pekkan and Füsun Önal. Selda Bağcan, on the other hand, is commonly known as a female representative of Turkey’s psychedelic scene. Her artistic background and inspirations, however, have always been rooted in Turkish folk music. Bağcan’s revolutionary attitude was informed by both folk music as well as her own life story. A representative of the worldwide 1968 movement of freedom fighters, she told me – as we discussed music and politics before the 1980 coup d’état in Turkey – that folk music was an important medium for expressing important matters of freedom and social justice. While Bağcan and German are more well-known, Esmeray – another female Turkish singer – is not. A singer of African origin, Esmeray combined Turkish folk with jazz and soul music, and introduced totally new sounds to Turkish folk music. She passed away in 2002, not having been given the recognition many felt she deserved.

Bright Lights, Big City

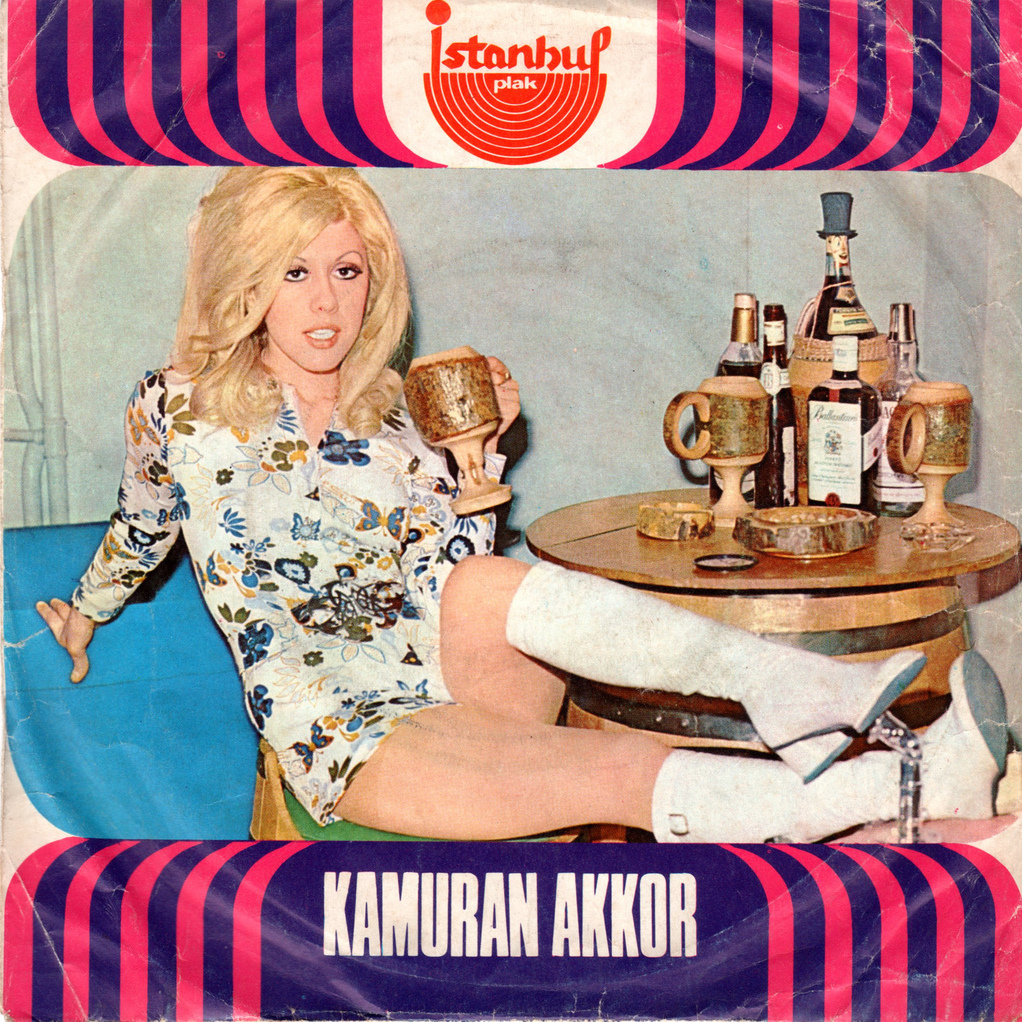

The phenomenon of the Arabesk genre is interesting and inspiring in terms on both a local and global scale. This margnialised musical culture of poor immigrants quickly shifted from the fringes of society to the centre of public appreciation, gaining respect and admiration beyond classes, ages, and ethnicities in Turkey. Following the release of Orhan Gencebay’s Bir Teselli Ver (Console Me), it became a hip and popular musical genre. In the beginning, such music was largely performed by men; however, artists such as Gülden and Neşe Karaböcek, Kamuran Akkor, Gülcan Opel, and Gönül Akkor also made names for themselves and grabbed my attention in particular, with their songs featuring Oriental orchestration, groovy sounds, and heavy, melancholic, and dramatic lyrics and vocals, along with frenetic belly dance sounds and rhythms from Egypt and Lebanon.

Şerefe! (A Kamuran Akkor single from the 70s)

Kamuran Akkor, especially, stands out as a prime example of such female musicians of the era. Her 1971 song Bir Teselli Ver, for instance, combines a subtle Latin brass section with the energy of the Arabesk genre, giving it at once a familiar and foreign sound. Gonül Akkor, on the other hand, can be considered as Akkor’s gloomier sister. Dost Bildiklerim (The Dear Friends I Knew) showcases everything characteristic of Arabesk music – fatalism, sadness, and an overwhelming aura of misery as a result of the hopelessness brought about by poverty. The role of women in Arabesk music has been altogether minimal, though. It was mostly men who moved to the big cities in Turkey, and who became ‘heroes’ of the genre, such as Orhan Gencebay and Ibrahim Tatlises. The limited role of women in the genre was mostly stereotypical, with singers posing as seductive and beautiful songstresses. Interestingly, however, Arabesk provided an important medium for discussing transgender issues. The complexity of the genre was evident in songs by singers such as Zeki Müren and Bülent Ersoy, who questioned the macho image of the genre as well as masculinity in general.

New Beginnings

Similar to how Turkey has, since the mid-15th century, spanned both Europe and Asia, the popular Turkish music of the 60s and 70s incorporated both local and international sounds. Female singers, while exploring their Turkish identities, flirted with styles such as cha-cha, tropical, go-go, yé-yé, and rock and roll, producing music both appealing and unique. Traditional folk songs were reinterpreted by pop singers, who brought upbeat and Western sounds to well-known classics. This repetition of patterns, or constant remixing of traditional songs has been a sort of leitmotif in Turkish culture as a whole until today.

* * *

Upon returning from Turkey, I quit my job, as I understood there is too much to explore in life, and too little time. I will return again soon to Istanbul to dig in deeper, and to continue my search. I have a feeling I have just opened this beautiful little Pandora’s box …